Daniel Randall, Confronting Antisemitism on the Left: Arguments for Socialists (London: No Pasaran 2021)

Holding a slice of kosher pizza, a friend and her yarmulke-wearing partner asked about the rally I’d attended against the Israeli bombing of Gaza last May. Politically Left-leaning and deeply critical of the Israeli government, the couple might have considered attending the rally. I wanted to look them in the eyes and tell them they’d have felt fully welcome. But I would have been lying.

The truth is that when I asked for a chant idea, a protester suggested, “Palestine is our homeland, and the Jews are our dogs.” The truth is that signs and speeches advertised the nationalist group If Americans Knew, whose founder Alison Weir claims medieval Jews ritually sacrificed Christian children.1 The truth is that my friends might have encountered a local anti-war activist who proudly supports Hamas, a group whose senior official Fathi Hammad had recently announced, “People of Jerusalem, we want you to cut off the heads of the Jews with knives.”

That month, a fringe of protesters across America invoked ugly tropes of deicide and Jewish control, with signs saying “Jesus was Palestinian and you killed him too” and “Israel controls the media.” Jewish buildings were targeted with “Death to Israil” [sic] graffiti and a Palestinian flag alongside a smashed window. There were even allegations, some more credible than others, of anti-Zionists physically assaulting Jewish individuals.2 Meanwhile in the United Kingdom, a Palestinian flag-decorated car convoy drove through Jewish neighborhoods shouting, “Fuck the Jews, rape their daughters.” The following month, former U.S. Green Party presidential candidate Cynthia McKinney shared an image of the 11 September 2001 attacks with the caption, “Zionists did it.”

It’s true that Left antisemites have generally adopted more subtle rhetoric since 1952 when Stalin declared, “Every Jew is a nationalist and an agent of American intelligence.” Today’s antisemites often use coded language for Jews, similarly to how white supremacists use “thugs.” These words and actions nonetheless fit the recent Jerusalem Declaration’s definition: “Antisemitism is discrimination, prejudice, hostility or violence against Jews as Jews (or Jewish institutions as Jewish).”3 More importantly, they contribute to a structural antisemitism that, regardless of individuals’ intent, and even aside from its effect on Jews, hinders any attempt at emancipatory change. Disproportionately obsessing over Jewish bankers or the Jewish state distracts the Left from opposing its real enemy: a more intangible system that the late Black feminist scholar bell hooks called “imperialist white-supremacist capitalist patriarchy.”

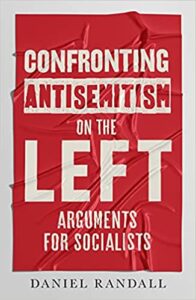

In this context, British socialist Daniel Randall’s Confronting Antisemitism on the Left: Arguments for Socialists provides an important intervention. As Randall demonstrates, Left antisemitism is all too real, has especially strong roots in Stalinism and its legacies, and functions as a dangerous frame for conspiratorial thinking. The book’s publisher, No Pasaran, was formed in 2019 to republish Steve Cohen’s 1984 classic That’s Funny, You Don’t Look Anti-Semitic. Randall’s book brings Cohen’s cutting analysis to the present day. Although Randall rightly draws much inspiration from Cohen, it’s unfortunate in my view that he disavows Cohen’s “utopian, semi-anarchist streak” (138). Cohen advocated a “no-state solution,” a vision I strongly support (while also welcoming the shorter-term one-democratic-state aspiration). By contrast, Randall supports the mainstream two-state settlement which denies full equality to Palestinians within Israel’s borders and prevents Palestinian refugees from exercising their right of return.4

Randall knew of our disagreements when he asked me to review this book, and one thing I appreciate about his approach is his commitment to open and respectful debate. Of course, anti-Zionists like myself will have numerous disagreements, which I’ll summarize in the next section. But first, let me say that Randall’s readers will find thoughtful and often convincing analysis of Left antisemitism’s history and contemporary relevance, as well as strategies for combating it. It’s a timely guide that helps us confront a pressing problem on today’s Left. In fact, I gave a copy to my aforementioned friends for Hanukkah, and I’ll especially be encouraging my anti-Zionist friends to read it too.

“You can’t weaponise something that isn’t there”

Randall’s volume is not and doesn’t pretend to be a comprehensive guide to fighting antisemitism. Importantly, the title is Confronting Antisemitism on the Left rather than Confronting Antisemitism from the Left.5 Readers will need to look elsewhere for an analysis of antisemitism on the Right. To be very clear, antisemitism remains most pervasive on the Right and strongly coincides with xenophobia and Islamophobia. Since support for Zionism is also stronger on the Right, antisemites are more likely to be Zionists than anti-Zionists. As Israeli-American ethnographer Atalia Omer observes, “White nationalists take from Euro-Zionism’s textbook aspirations for ethnoreligious supremacist political hegemony.” For example, U.S. far-right rallies fly the Israeli flag, and Richard Spencer (who has called Jews “little fucking k*kes”) has famously identified as a “white Zionist” and expressed “great admiration for Israel’s nation-state law.” In the United Kingdom, antisemitic beliefs are highest on the political Right and Center, and in Germany, where the fascist Alternative for Germany (AfD) party holds pro-Zionist views, more than 9 in 10 antisemitic incidents between 2001 and 2020 came from the Right.

It’s sheer opportunism, then, when establishment Christian and Jewish Zionist groups have often classified anti-Zionism as inherently antisemitic and have thrown accusations disproportionately and falsely against the Left and especially people of color. For example, Zionist groups smear the entire Palestinian-led Boycott Divest Sanctions (BDS) movement as antisemitic, and CNN pundit Marc Lamont Hill was fired merely for advocating “a free Palestine from the river to the sea.”6 Black-Jewish peace activist Rebecca Pierce was falsely labeled a “Jew Hater” and “Antisemite of the Week,” and even a “fake Jew.” To say anti-Zionism is antisemitic is itself antisemitic and defamatory, since it falsely essentializes Jews as Zionists.

Facing this pervasive antisemitism on the Right alongside a barrage of false accusations against the Left, many socialists and progressives pay almost no attention to Left antisemitism at all. You’ll find virtually no critical discussion of Left antisemitism in popular Left-wing books such as The Politics of Anti-Semitism (Counterpunch, 2003), On Antisemitism (Haymarket, 2017), or Antisemitism and the Labour Party (Verso, 2019). To the contrary, you’ll read this charming sentiment on page 1 of the former: “I think we should almost never take anti-Semitism seriously, and maybe we should have some fun with it.” And yet people wonder why more Jews aren’t showing up to our Palestine solidarity rallies, despite a quarter of American Jews opposing Zionism.

Randall helpfully stakes a clear position between those denying Left antisemitism and those opportunistically “weaponizing” the accusation against the Left: “Antisemitism has indeed been ‘weaponised’, but as the socialist writer and lawyer David Renton succinctly argues: ‘You can’t weaponise something that isn’t there’” (5). Well, you could weaponise basically anything, but the claims of Left antisemitism would not gain currency unless there were some kernel of truth behind them.

A main danger of a book like Randall’s, which draws on the important critique of structural antisemitism, is that it could easily lead to a hyper-sectarian and suspicious politics as the communist theorist Gerhard Hanloser describes:

“The critique of ‘structural Antisemitism’ and ‘truncated anticapitalism’, which has congealed into jargon, lays a protective hand over the ‘character masks’ of capitalism and its institutions–although this favor hasn’t even been requested. It trivializes Antisemitism by claiming to see it in every fetishistic expression of discontent with capitalism […] This theory opens the door to a politics of suspicion and accusation, a Stalinist tradition of politics is revived.”

It’s to Randall’s credit that he succeeds more often at avoiding this trap than do some commentators on Left antisemitism. Unlike some of the thinkers he cites, Randall makes a crucial distinction between antisemitism and anti-Zionism. He also seems willing to listen open-mindedly to his political opponents, regardless of their organizational affiliation. In my critical comments, I’ll try to follow his lead and will refrain from turning this review into either an argument against Zionism or a critique of the Alliance for Workers’ Liberty with which Randall affiliates. Instead, I’ll focus on what I find valuable and frustrating in Randall’s actual text.

My disagreement, in short, is that I see confronting antisemitism as one strand in a broader anti-oppressive praxis. I strongly agree, in other words, with a statement signed by 15 progressive Jewish groups (including Jewish Voice for Peace and Israel’s Boycott from Within): “Do not isolate antisemitism from other forms of oppression.” By contrast, Randall does not see antisemitism as a type of oppression, and he seems to approach confronting antisemitism as a distinct project that actually balances and moderates anti-oppressive struggles. I’m sure he’ll object to this characterization, but in my view it comes across in his lack of support for fully decolonizing Palestine and in his overly broad-brush critique of various New Left and decolonial politics that he rejects as “revanchism,” “identity politics,” “nationalist resentment,” and “anti-imperialism” (a term he uses pejoratively). It also comes across in the fact that his entire book never mentions what is probably Left antisemitism’s most widespread manifestation: Left-leaning Zionists’ ubiquitous claim that anti-Zionism is antisemitic. Though this claim, conflating Jewry with a settler nationalism, is reminiscent of the classic antisemitic trope that Jews cause wars, you’ll find it asserted as fact in The Nation, coming from a No Pasaran author, and even in some far-Left circles.

A State Capitalism of Fools

Discussions of Left antisemitism often reference German Social Democrat Augustus Bebel’s supposed condemnation of it as “the socialism of fools” in the 1890s. Actually, the term can be traced back earlier to the Austrian liberal Ferdinand Kronawetter who in 1889 declared, “Antisemitism is nothing but the socialism of the idiot of Vienna [i.e. village idiot].” When Bebel later described the “socialism of fools,” he did not outright oppose it but instead saw it as a progressive step toward a holistic socialism (54-5). While these factors suggest limitations with the oft-used term, a further problem is that Left antisemitism has its strongest roots not in genuine socialism but in Stalinism. Depending on our preferred analysis,7 we might be better off calling it a “state capitalism of fools” or “bureaucratic collectivism of fools.”

Although Randall points to antisemitic remarks in the writings of Marx and Bakunin, these remarks were not significant aspects of the anti-capitalist ideologies they influenced. While Marx’s “On the Jewish Question” called Jews money-obsessed hucksters, it paradoxically did so in the context of supporting Jewish emancipation. Bakunin’s antisemitic comments remained obscure to generations of historic Anarchists. In an interview with Shane Burley in these pages, Randall explains that this 19th century variety is better understood as antisemitism “on the left,” a spillover from society at large, rather than antisemitism more specifically “of the left.”

The more pertinent origin for today’s “antisemitism of the left,” lies with Stalin’s government which employed antisemitism beginning in the 1920s. As Trotsky recounted of the government’s repression against the Left Opposition:

“[T]he bureaucracy purposely emphasised the names of Jewish members of casual and secondary importance. This was quite openly discussed in the party, and, back in 1925, the Opposition saw in this situation the unmistakable symptom of the decay of the ruling clique” (67).

Surprisingly, Randall’s historical summary skips over virtually the entire 1930s and 1940s, despite these being crucial decades of Stalinist antisemitism. By 1931, the Communist International opportunistically supported Hitler, as summarized by the slogan “After Hitler, our turn,” reflecting at best an extreme insensitivity to the fate of German Jewry. As German antifascists complained at the time, “Without Stalin, no Hitler.” Randall does not mention the 1939 Hitler-Stalin pact which enabled the Second World War, and under which the USSR granted Germany the use of the Kola Peninsula as a secret naval base. Nor does Randall mention that Stalin in 1940 sought to formally join the Axis powers, only abandoning the idea because Hitler required him to be more a junior partner than an equal.

Although Randall mentions a number of infamous incidents of Stalinist antisemitism–the 1948 assassination of Jewish Anti-Fascist Committee head Shloyme Mikhoels and subsequent forced dissolution of the organization, the 1952 Slansky Trial, and the 1951-3 Doctor’s Plot–he leaves out the most ominous part of the latter episode. There is strong evidence that Stalin planned, until his death, to mass deport Jews to concentration camps. As evidence of this plan, historian Jonathan Brent cites “documents dated February 1953 authorizing the construction of four new concentration camps in Soviet Asia confirm[ing] that Soviet authorities were preparing for a large influx of new political prisoners at a time when few remained after World War II.”

Randall is surely familiar with this history, but he speeds ahead to the 1950s and especially 1960s when the Soviet Union shifted from openly attacking Jews per se to attacking “Zionists.” Doing so, he tends to overstate the centrality of anti-Zionism in Stalinist antisemitism and its legacies on the Left. After all, as Randall points out, the Soviet Union held a pro-Zionist position in 1948. The Soviet bloc, through Czechoslovakia, supplied crucial arms to the Zionist paramlitary force known as the Haganah, and the Soviet Union was the first country in the world to diplomatically recognize Israel. When the United Nations General Assembly passed Resolution 194, securing Palestinians’ right of return, Moscow and the entire Soviet bloc voted against it. In 1949, Soviet-controlled Poland repressed and dissolved the anti-Zionist Jewish Labour Bund, almost a year before it dissolved Zionist organizations. While Stalinism flipped between supporting and opposing Zionism, its antisemitism remained consistent.

Clearly, the Soviet campaign against Zionism in the late 1960s and 1970s contained much blatant antisemitism, and Randall is right to condemn it. One would read in the Soviet press, for example, “The peculiarities of Jewish religion are hatred of mankind, preaching genocide, cultivating a love of power, and glorifying criminal means of achieving power.” The problem isn’t an opposition to the Jewish religion, which is to be expected from a staunchly atheist perspective, but it’s the singling out of Judaism for alleged “peculiarities.” Randall quotes an official Soviet denunciation of a global “monopoly bourgeoisie of Jewish origin,” a formulation that resembles the shadowy networks alleged in the Protocols of the Elders of Zion (76). It’s important to emphasize that this antisemitism was imported from Moscow’s earlier era, including its pro-Zionist period, and not from the Palestinians’ struggle.

We can contrast Moscow’s antisemitic rhetoric of the period with the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO)’s rejection of antisemitism. In 1970, the PLO went so far as to publish a book defending the Talmud and debunking common antisemitic myths. As Yasser Arafat famously informed the United Nations in 1974, the Palestinians’ enemy “has never been the Jew, as a person, but racist Zionism and aggression.” The PLO officially maintained since the late 1960s (admittedly in outward-facing English-language documents) that Israeli Jews had acquired a right to stay and be equal citizens of a decolonized Palestine.8 Such facts should confirm what Palestinians themselves have long insisted, that their struggle against Zionism is rooted not in antisemitism but in principles of liberty and equality. This is not to deny antisemitic tendencies within the struggle, including within the leadership. However, when the Soviet Union made anti-Zionism a central campaign in the 1960s, and when it attached highly antisemitic motifs to this campaign, it opportunistically adopted and distorted a movement it had previously betrayed.

Parallel to how Sri Lankan-Indian author Rohini Hensman rejects a pseudo-anti-imperialism that supports Russian and Chinese imperialism, I propose we denounce the “pseudo-anti-Zionism” that only opposes Zionism for reasons that are opportunistic, campist, and ultimately reversible. Were the geopolitical situation to change, the campist Left would determine their stance based on the world chess game rather than actual solidarity with Palestinians. One giveaway is the campists’ indifference to the thousands of Palestinians murdered by Bashar al-Assad. Another is that Communist Parties worldwide, including the UK’s (96) and China’s, advocate a two-state solution which preserves a Zionist state.

I’ve often been told that antisemitism doesn’t exist on the Left or that it’s not important to analyze. Open-minded readers looking for present-day examples are likely to be persuaded by Randall’s presentation. Some of his examples, coming mainly from the British Left, might seem insignificant or even misplaced in isolation, but they comprise a worrying trend when observed altogether. It must be emphasized, though, that that the UK Labour Party and its 2019 candidate Jeremy Corbyn supported a two-state solution, and therefore their entanglements with antisemitism cannot be blamed on anti-Zionism.

The fact that Labour’s antisemitism problem under Corbyn’s leadership has been wildly exaggerated does not mean that there was no problem. The most obscene antisemitism was online, with party members posting about “zioscum…behind all the conflict on the planet” and “Jews’ deceitful infiltration of UK’s politics” (39). But the problem extended offline with, for example, a party branch in 2018 voting down a motion condemning the recent Pittsburgh synagogue shooting. Branch members offered the reasoning, which at best was highly insensitivie just after the murder of 11 Jews, that there was too much focus on “antisemitism this, antisemitism that.” The problem also extended higher up in the party, with Corbyn’s advisor Chris Williamson defending numerous hardcore antisemites such as the blogger Vanessa Beeley who has claimed “Zionists rule France” and, bizarrely, that Kristallnacht was a “Mossad false flag.” Williamson also defended Gilad Atzmon before implausibly claiming he’d been ignorant of the activist’s well-known record of antisemitism including promoting Holocaust skepticism and the Protocols of the Elders of Zion. Another high-profile British Leftist, sociologist David Miller accuses most of organized Jewry, even groups with very indirect connections to Israel, of belonging to a nefarious Zionist network that he singles out as “the enemy of world peace” (23).9

Demonstrating the frequent entanglements between the Left’s versions of antisemitism and Islamophobia, the same campists who dabble in antisemitism also tend to support the repression of Syria’s and Xinjiang’s Muslim populations. Miller and Beeley collaborate in a Working Group on Syria that defends the Assad regime and smears Syrian civilians and the first-responder group, the White Helmets, as “jihadists.” Beeley’s Assadist propaganda has been published on various leftist websites including Counterpunch and Black Agenda Report, which have also boosted classic antisemitic tropes of exaggerated Jewish power by claiming that the United States is “a puppet state of the Israeli government” and “[t]he Israeli government tells the American government and by extension, the American people, what they will do and when they will do it.” Williamson shares campist views on Syria, as does Seamus Milne who, as Corbyn’s spokesperson, obscenely told the press that there was too much attention on Russian war crimes in Syria.10

Even if we might grant that Jeremy Corbyn as Labour Party leader had entirely good intentions, we would still have to admit that he made an astounding number of missteps, including: attending Holocaust-deniers’ events, calling Hamas and Hezbollah his “friends,” and defending a mural demonizing hook-nosed Jewish bankers plotting in front of an Illuminati symbol.

The fact that Randall mainly condemns an overall discourse, rather than condemning individuals, helps a critical reader forgive his handful of missed targets.11 I’ll focus on London’s former mayor Ken Livingstone, who inaccurately claimed that Hitler “was supporting Zionism before he went mad and ended up killing six million Jews.” To be sure, it’s an irresponsible and untrue claim. But to his credit, Livingstone later clarified, correctly, that the historian Lenni Brenner has documented a real history of Zionist collusions with antisemites and fascists. Examples include the Ha’avara, the Kastner affair, the Stern Gang’s 1941 offers to fight on the Nazis’ side of the war, U.S. Zionist leaders’ deprioritzation of rescue, and the State of Israel’s alliance with antisemitic heads of state such as Galtieri, Orbán, and Trump and with antisemitic activists including John Hagee. Though Randall dismisses such collusions as “incidental examples” (82), I see them as a logical extension of mainstream Zionist priorities, exemplified by Ben-Gurion’s infamous claim, “If I knew that it was possible to save all the [Jewish] children in Germany by transporting them to England, but only half by transporting them to Palestine, I would choose the second.”12

For Jewish Liberation

“Who cares lol,” commented a member of the Democratic Socialists of America (DSA)’s Jewish Solidarity Caucus when I posted an exchange by Randall and David Renton about Left antisemitism. Randall gives seven important reasons (205-207) why we should care about Left antisemitism, but I will give just two of my own. Firstly, as I’ve said already, antisemitism hurts the Left’s emancipatory project by distracting us from opposing capitalism and its entangled oppressions. Because capitalism functions in a highly abstract manner, sometimes theorized as an “invisible hand” or “law of value,” antisemites from Left to Right take a shortcut and identify a more personalized target.13 Jews are seen, as critical theorist Werner Bonfeld summarizes, as a “puppet-master of the world.”

Secondly, antisemitism should be opposed since it’s a type of oppression. I depart here from Randall who considers today’s antisemitism to be merely a type of bigotry. He explains, “I believe that for the conception of oppression to have meaning, it must refer to something structural and systemic–a relation of power, not only speech or ideas” (175). I think that Randall can only come to this conclusion by focusing narrowly on the immediate present rather than looking at the longue durée. Although Randall admits that “most Jews’ integration into whiteness is both recent and precarious,” (177) I wish he would go further and acknowledge that antisemitism is a “cyclical” oppression.

As The Past Didn’t Go Anywhere by April Rosenblum points out, antisemitism “moves in cycles” and, prior to massacres and expulsions, Jews have often tended to be “one of society’s most successful, comfortable, well-integrated minorities.” The precarity of white Jews’ whiteness has been stressed by anti-racist researches including Eric Ward, Karen Brodkin, Leo Ferguson, Dove Kent, and Keren Soffer Sharon. Jewish liberation needs to strive for a more permanent liberation, and it requires abolishing whiteness rather than assimilating into it.

Interpreting antisemitism as a form of oppression helps us situate it more organically into a broader anti-oppression framework. An understanding of antisemitism’s entanglement with other oppressions can help us explain how antisemitism has long interlocked with Islamophobia since the Crusades, how Spanish anti-Jewish limpieza de sangre statutes helped construct today’s racial capitalism, and how antisemitism lies at the center of today’s white nationalism. It assists us in connecting far-Right Islamophobia to antisemitism, and understanding why, for example, the 2018 Pittsburgh synagogue shooter Robert Bower had written on social media, “It’s the filthy EVIL jews Bringing the Filthy EVIL Muslims into the Country!!”

Situating anti-antisemitism firmly in an anti-oppressive framework can help us focus on how colonialism of Third and Fourth World peoples ultimately comes back to hurt the First World’s marginalized minorities including Jews. The Nazis repeated tactics from Germany’s 1904-1908 racial genocide against Southwest Africa’s Herero and Nama, and Hitler studied European settler-colonialism and segregation in North America. A decolonial approach to uprooting antisemitism should include Aime Cesaire’s analysis: “[Hitler] applied to Europe colonialist procedures which until then had been reserved for the Arabs of Algeria, the ‘coolies’ of India, and the ‘n***ers’ of Africa.” Although Randall aspires to oppose all colonialism and oppression, he cannot do so because he strongly rejects an “absolute” anti-Zionist politics (104). It is from here that I must start disagreeing with him more strongly.

Smash Zionism, Not Israel

Early in his monograph, Randall approvingly quotes my 2021 New Politics article, “In Support of Joint Struggle” which distinguished between anti-Israelism and anti-Zionism. As I understand it, anti-Israelism is opposition to the people of Israel, whereas anti-Zionism is opposition to a Jewish supremacist state within historic Palestine. I identify as anti-Zionist but not anti-Israeli in the same sense as I identify as anti-Hindutva but not anti-India, as anti-Nazi but not anti-German.14 Randall includes a block quote from my article:

“Anti-Israelism is [musician] Roger Waters conjuring up a false story about Israeli concert attendees failing to applaud his call for regional peace. Anti-Israelism is […] Socialist Worker declaring ‘unconditional’ support for Hamas, a far-right group that intentionally kills Israeli civilians. Anti-Israelism is [feminist academic] Judith Butler bizarrely remarking, ‘Yes, understanding Hamas and Hezbollah as social movements that are progressive, that are on the left, that are part of a global left, is extremely important.’ Maybe more Israeli Jews would join the global left if they felt as invited as their theocratic enemies are.”

I’m flattered to be quoted, and I partially agree with Randall that it’s “precisely at the point of ‘conflation’ of anti-Zionism with ‘anti-Israelism’ that contemporary left antisemitism resides” (33). I’m not sure it’s helpful to call all anti-Israelism antisemitic, although it should be opposed for strategic and ethical reasons. It would be an unhelpful stretch, for example, to call Butler’s absurd comment antisemitic, since she did immediately follow it with an appeal toward “being critical of certain dimensions of” these groups.15

I’m concerned that, at times, Randall himself conflates anti-Israelism with anti-Zionism, wrongly seeing all maximalist or “absolute” forms of anti-Zionism as necessarily anti-Israel. When he denounces the Left’s “Smash Israel” tendencies (138), he sometimes seems to include not only armed attacks on Israeli civilians but even the BDS movement that adopts highly principled and life-respecting means and ends.16 Randall writes that anti-Zionism becomes antisemitic at “the point at which it insists Israel’s very existence, not merely its policies, is illegitimate” (33-34). The problem is that “Israel” can refer to either a nation or a state, and Randall is ambiguous about which one he means.

Before proceeding, I want to clarify that I’m using today’s standard definition of “Zionism” to mean, specifically, the political Zionism founded by Theodor Herzl and Christian cleric William Hechler.17 As Randall puts it, “Zionism’s central policy aim” is “the realisation of Jewish nationhood in the form of an independent state in historic Palestine” (19). The definition of Zionism may have once been much more open, with bi-nationalist Zionists like Martin Buber and Hannah Arendt being included in the fold. Today, however, those viewpoints are widely considered anti-Zionist since they oppose an exclusive Jewish state.

Randall is correct that it would be unreasonable to expect Israeli Jewry, uniquely among nations, to give up their national identity. But their status as a nation does not give them a right to statehood. I would be supportive of transforming the land of Canaan into a democratic country dually named Palestine/Israel, and I would be supportive of Israeli Jews continuing to speak Hebrew and identify as Israeli as one nationality in a plurinationalist society that also includes Palestinian Arabs, Druze, Bedouins, and others. And I agree with the Israeli socialist organization Matzpen’s historic call for “a de-Zionization of Israel and its integration in a socialist Middle Eastern union.” Typically, Zionists who hear my position conclude that I’m “anti-Israel.” They’re right insofar as they mean I’m against the current state of Israel. In fact, I’m against all states. But I’m not against the Israeli country or nation.

Unfortunately, Randall suggests that in almost all cases it’s antisemitic to oppose the existence of the state (not just the country) of Israel. This can be seen, first of all, in his repeated insistence that all nations including Israeli Jews have a right to a nation-state. A consistent internationalism, he wrongly contends, “supports the right of national groups to self-determination and, if they wish, to statehood” (139). Repeatedly, he defends the state of Israel’s “existence” and “right to exist” (33, 107). Although he’s justified to denounce as antisemitic the insistence that all nations except for Israeli Jews have a right to a state, I don’t think that very many Leftists actually hold such position.

Even putting aside the strict anti-nationalists and Anarchists whom Randall claims are “highly minoritarian” within the Left (121), the fact is that none of the major Marxist positions on nationalism, including Lenin’s, Luxemburg’s, and the Austromarxists’, said that all nations have an unqualified right to a state. Even the Left-liberal position doesn’t say this, for reasons Peter Beinart puts succinctly in “There is No Right to a State”:

“Create a state that privileges one people in a territory that contains multiple peoples, and you’ll likely deny members of those other peoples both the individual right to be treated equally under the law and the collective right to run their own affairs. For that reason, most political theorists insist that national self-determination cannot mean the right to your own state.”

Because of these conflicting claims, a logically consistent version of national self-determination should be based on a principle of true self-governance rather than governance over others. The late ex-Panther Russell Maroon Shoatz helpfully elaborated a theory of “Inter-Communal Self-Determination” that, disavowing any nation’s unilateral control over a large area, envisions a “mosaic” in which each community governs itself. The communities, overlapping in membership and geographically, cooperate to promote sustainability and peace. I also refer to Kahala Johnson and Kathy Ferguson’s exploration of Indigenous and Anarchist understandings of “sovereignty” as “a plural and contested set of possibilities” based on principles of “autonomous communities, integral living, and prefigurative politics.”18

Part of smashing Zionism has to involve linking it to struggles against other forms of statist nationalism. Randall quotes anti-fascist researcher Spencer Sunshine: “The important thing here is not to say, ‘Israel is not as bad as other countries, so it needs to be left off the hook’ … [T]he question is ‘Why is Israel on the hook when other countries are not?’” (115). Exactly, we need to put all countries on the hook. While opposing Israeli apartheid, we need to also oppose U.S. apartheid, for example.19 While opposing Israel’s war crimes, we need to oppose the war crimes of its immediate neighbor Syria.20 This doesn’t mean we need to employ the same exact strategies and tactics in all situations. Supporting a boycott of Israel doesn’t automatically imply that there’s a moral or strategic necessity to boycott China, for example, although I do think we should honor Uyghurs’ and Tibetans’ calls to boycott the 2022 Beijing Olympic Games. However, supporters of BDS, like myself, should practice some basic self-awareness. It looks downright goofy when we tweet: “If you want to celebrate [the Jewish festival of] Chanuka and support BDS, these candles are made in China – we can’t certify the working conditions unfortunately” (123).

I’m intrigued but ultimately not convinced by Randall’s defense of That’s Funny author Steve Cohen’s concept of “anti-Zionist Zionism.” Cohen defined it in a 2005 poem that read in part:

“Yesterday I was an anti-Zionist Zionist/ Today I’m a Zionist anti-Zionist/ Either way it negates the negation/ Of the tribal nation.”

Resurrecting this formulation, Randall makes a valiant attempt to rescue nuance and sensitivity to the trajectories of two historically oppressed peoples. What it doesn’t offer, however, is clarity. Even Cohen admitted this formulation is meant to “confuse the bastards” (135). A major problem with Cohen’s idea of the “anti-Zionist Zionist” is that it describes as “Zionist” a position that’s not necessarily Zionist at all. This is the belief that Jews should be able to seek refuge in the land of Palestine/Israel, that the country should be what Isaac Deutscher called a “lifeboat” for Jews in an ocean of antisemitism. This position does not require support for a Jewish state!

In fact, some of the most hardcore anti-Zionists agreed that the land of Palestine/Israel can and should serve be a refuge, ideally one of many, for Jews and other people fleeing oppression. The New York Times reports that Boycott Divestment Sanctions co-founder Omar Barghouti believes a “democratic state could still provide asylum for Jewish refugees, showing ‘some sensitivity to the Jewish experience.’” Such hardcore anti-Zionists as Palestinian intellectual Edward Said, Electronic Intifada co-founder Ali Abunimah, and Al-Haq co-founder Jonathan Kuttab have even said that a single democratic state should maintain Israel’s Law of Return, granting the world’s Jews potential citizenship as long as it doesn’t supplant Palestinians’ own right of return. Even Arafat declared in 1974, “If the immigration of Jews to Palestine had had as its objective the goal of enabling them to live side by side with us, enjoying the same rights and assuming the same duties, we would have opened our doors to them, as far as our homeland’s capacity for absorption permitted.”

What Arafat touched on is the difference between immigrants and settlers. Ugandan political theorist Mahmood Mamdani distinguishes, “Immigrants come in search of a homeland, not a state; for settlers, there can be no homeland without a state.” Intentions alone are not sufficient to distinguish immigrants from settlers, since most Jews who settled in Palestine after 1923 were probably not ideological Zionists. They were fleeing and leaving antisemitic countries of Europe and the Middle East. Nonetheless, they joined a settler society, rather than struggling to decolonize it, and therefore they became settlers.

Although external pressure is essential, Moshe Machover convincingly argues that Zionism can’t be overthrown without substantial support from within the Israeli Jewish working class. Therefore, Palestinians and their anti-Zionist accomplices21 need to advance an appealing vision and transnationalist politics that can win over a substantial portion of Israeli Jews.22 Clearly, a principled alternative to pseudo-anti-Zionism and anti-Israelism is needed. Nonetheless, I don’t think “anti-Zionist Zionism” is the answer. What’s needed is a clearer vision that convinces Israeli Jews they can live safely and freely in as a de-Zionized country.

Beyond Our Comfort Zones

I mentioned that I bought an extra copy of Randall’s book for my Jewish friends, and I hope it might convince them that, despite antisemitism’s ongoing existence on the Left, we Leftists are at least discussing it and seriously trying to uproot it. In other words, we are getting out of our comfort zones and are trying to engage with mainstream Jews, not just far-Left Jews like myself, but also with liberal Zionist Jews. I can only hope that Zionist Jews will return the favor and will start engaging openly with anti-Zionist voices and ideas, instead of smearing us all as antisemites. At a time when many people seem most comfortable screaming “antisemite” and “Zionist” at each other, Confronting Antisemitism on the Left suggests a healthier approach. Randall argues, “The tools primarily required to conduct that confrontation [with Left antisemitism] are not complaints, suspensions and expulsions but debate, polemic and education” (184). He proposes reading groups, collective education, direct debates, practical solidarity on Palestine/Israel, and reengagement with the Left’s foundational ideals.

Reading groups and collective education are great ideas, and Randall helpfully recommends Cohen’s 1984 That’s Funny, Rosenblum’s 2007 The Past Didn’t Go Anywhere, and the 2019 Journal of Social Justice issue on “Confronting Antisemitism in the 21st Century.” All three are invaluable resources, but I would recommend starting instead with Jews for Racial and Economic Justice’s Understanding Antisemitism which was written in 2017 by “a multi-racial, multi-ethnic, intergenerational team” of Jews mainly based in New York City. It’s more up to date than Cohen’s and Rosenblum’s resources, and it avoids the “anti-anti-Zionist” leanings of some of the Journal of Social Justice’s contributions. For further reading, I would recommend the American Historical Journal’s 2018 roundtable on “Rethinking Anti-Semitism” which emphasizes antisemitism’s historic entanglement with colonialism, Islamophobia, heteropatriarchy, and Zionism.

Next, Randall advocates public debates over questions such as, “What is Zionism? What is the real extent of Israel’s power in the world? Should the Israeli-Jewish national group be entitled to self-determination?” These are important topics, but I think it would be useful to broaden the questions. Let’s discuss and debate what is an operable understanding of self-determination that could apply not just to the Middle East’s Jews but also to Kurds and other regional minorities without interfering with Arabs’ self-determination including Palestinians’. How do we apply the same principles in North America? To what extent are the imperialisms of West and East intertwined?

As forms of practical solidarity on Palestine/Israel, Randall advocates support for a number of Israeli initiatives bringing together Jews and Palestinians in joint struggle for social justice. These include Koah LaOvdim, Standing Together, and Combatants for Peace (200-201). None of these efforts are explcitly anti-Zionist and some take a liberal Zionist position. I would argue, nonetheless, that critical support and friendly critique, rather than hostile opposition, is the best way to encourage their members to move dialectically toward increasingly decolonial positions, as B’Tselem did last year when it finally denounced “A regime of Jewish supremacy from the Jordan River to the Mediterranean Sea.” More radical Israeli groups that one can support include Boycott from Within, Israeli Coalition Against House Demolitions, and +972 Magazine. An important 2021 statement from 1,000 Israeli Jews supported the BDS movement’s demands including Palestinians’ right of return, and called for “decolonization of the region and founding a state of all its citizens.” Another hopeful development has been growing Jewish support for Israel’s Joint List of Israeli-Palestinian political parties. We can hope this support will continue to grow, especially for the secular-democratic Balad Party.

Finally, Randall advocates reengagement with some of the Left’s fundamental ideas. For instance, this means returning to an old-school “Marxist understanding of capitalism” that targets the whole system rather than just “the 1%” (201). For national questions, he advocates approaches that “emphasise democracy and equal rights” and eschew the “statist left-nationalism” that often predominates today (201-202). These are fine suggestions, but I think that a lot of answers to national questions including the “Jewish question” will be found outside of traditional Marxism, which basically expected Jews to assimilate. Randall embraces Deutscher’s identity of the “non-Jewish Jew” and he envisions a distant future that “fuses what is best in all cultures into a universal synthesis” (227). By contrast, I don’t envision a universal culture but rather a permanently decentralized world interconnected from below, or what the neo-Zapatistas call the “world where many worlds fit.” In a despiritualized and commodity-worshiping world, I’d even argue that the more radical Jewish perspective today isn’t becoming “non-Jewish” but instead embracing a Jewish resurgence. This is not to uphold Judaism’s heteropatriarchal tendencies or even its (mono)theism, but rather to advance its liberatory and ecological principles such as choosing life, loving your neighbor, tikkun olam (repairing the world), bal taschit (not wasting natural resources), tza’ar ba’alei chayim (kindness to animals), and the commandment that “Justice, justice, you shall pursue.”

Whereas Randall asserts that antisemitism “must be confronted almost exclusively at the level of ideology” (181), I believe that we need to confront it also in material and social-psychological terms. This means, in part, looking at how campist and conspiracist politics, a main source of Left antisemitism and Left-Right overlap, has become a lucrative business and spreads through organizations that are well funded from wealthy rather than grassroots sources. It also means applying Critical Theory’s insights into how authoritarianism, including Left authoritarianism, thrives on destructive urges that need to be strongly countered with what Herbert Marcuse called Eros and what Erich Fromm called biophilia. Thus, while Randall sees the main solution as engaging in intellectual discussion and education, I see an equally important solution as being the creation of a joyful militancy. Basically, we non-campist Leftists need to build a life-affirming alternative–culturally, structurally, and intellectually–to the campists’ activist pseudo-community.

I’d recommend Confronting Antisemitism on the Left to anyone interested in advanced-level politics around Jewry, antisemitism, Palestine, and Zionism. I’d also point those same readers to important scholarship by Palestinians, such as Noura Erakat’s Justice for Some (Stanford University Press, 2019) and Rashid Khalidi’s The Hundred Year’s War on Palestine (Metropolitan Books, 2020). I’d then point them to the Israeli and American Jewish perspectives offered by Jeff Halper’s Decolonizing Israel, Liberating Palestine (Pluto Press, 2021) and Stan Heller’s Zionist Betrayal of the Jews (SH Books, 2019). If Randall’s right that it’s antisemitic to demand Israeli Jews give up their national identity, then surely it’s even more bigoted when mainstream Zionism demands that Palestinians give up their nationality, despite Palestinians being the land’s clearly oppressed and Indigenous people. The fight against the apartheid state of Israel and the fight against antisemitism are inseparable. As the name of an Israeli Veganarchist group once put it, Jews and other oppressed people are all engaged in “One Struggle” against interlocking dominations.23 In summary, the struggle against antisemitism is a struggle for Jewish liberation, and the struggle for Jewish liberation is a struggle for total liberation.

An addendum: As I was finalizing this review, I learned that the publisher No Pasaran is apparently run by Baron Jonathan Mendelsohn, a centrist-Zionist philanthropist and life peer in the House of Lords. I also learned that fellow No Pasaran author Ben Freeman appears to share some of the Menachem Begin Heritage Center’s Likudnik politics.

This information will surely turn away some potential anti-Zionist readers from Randall’s book, if they haven’t already been turned away by Randall’s association with the Alliance for Workers’ Liberty. That would be unfortunate. Randall is an independent thinker whose views are by no means identical with those of Baron Mendelsohn nor with the AWL’s Sean Matgamna.

I hope that a book on Left antisemitism will one day come from an author and publisher with impeccable anti-Zionist credentials. In the meantime, Randall’s study, for all its serious flaws, is probably the best available book on the subject and deserves to be engaged seriously on its own terms.

1 Weir’s own source, Israel Shahak, actually referred to the infamous “blood libel” as an “ignorant calumn[y…] propagated by benighted monks in small provincial cities.” Weir also cited historian Alan Toaff who has rejected the claim. Israel Shahak, Jewish History, Jewish Religion: The Weight of Three Thousand Years (London: Pluto Press, 2002), 21.

2 For example, it’s alleged that New York protesters assaulted a Jewish man, Joseph Borgen, wearing a visible yarmulke, but video footage shows Borgen wearing a hood that would have hidden any yarmulke. Referring to eyewitness testimony, the Twitter account of Outlive Them NYC, (a Jewish-led, anti-fascist group) described the incident as “a Zionist instigating a fight and then crying hate crime.” Friends of a suspect also told the New York Post that Borgen attacked first. It has also been widely reported that protesters threw a firework in a mostly Jewish business district, but as the New York Times reports, “police said they were unsure who had thrown the firework.” Protesters in Los Angeles are accused of assaulting restaurant diners and using antisemitic slurs, but the Forward notes that the facts are still under review. Finally, Jewish Currents reports a claim that “a Jewish couple at a Westlake, Ohio, pro-Palestine rally were allegedly attacked by protestors, has been disputed online: A Twitter user said they attended the rally in question and that the couple actually showed up to attack protestors with a flagpole.”

3 This remains true even if antisemites identify a minority of “good Jews,” similarly to how Islamophobes identify “good Muslims” and white supremacists have “Black friends.”

4 I strongly disagree with Randall’s rejection of the so-called “maximal” version of Palestinains’ right of return. First, he says, the inclusion of refugees’ descendants puts the right of return “to a different discourse than a general advocacy of free movement and open borders.” Second, Randall quotes a policy statement saying that a right of return implies “Jews […] be driven out of their homes so that their original Palestinian owners may be housed in them.” I disagree with both claims. It is the United Nations’ standard practice in protracted refugee situations to classify the descendants as refugees. We should advocate an intergenerational right of return for descendants of Palestinian refugees just as fiercely as we advocate it for children of Syrian refugees, for example. The claim that returning Palestinian refugees would necessarily displace Israeli Jews ignores important research suggesting otherwise. As Palestinian advocacy group Badil explains:

“Moreover, it is estimated that in 90% of the communities from which Palestinian refugees originate inside Israel, there is no conflict with existing built-up Jewish communities. In other words, the return of Palestinian refugees would not result in the displacement of the existing Jewish population from their homes and communities. In addition, international law and best practice provide creative solutions enabling refugees to return while maintaining and even developing the existing infrastructure.”

5 I don’t think Confronting Antisemitism ever defines “the Left,” but I’m using it to describe people who advocate a societal shift toward egalitarianism rather than hierarchy. I’m including Stalinists since they at least claim to believe their strategy will eventually establish a communism in which the state has withered away.

6 The phrase began historically, and continues to be used prominently, as a call for a secular democracy that treats Jews equally to everyone else in Palestine/Israel. Therefore, it cannot reasonably be called antisemitic. However, I understand why some Jews are uncomfortable with the phrase due to its similarity to the antisemitic refrain that Israeli Jews be “thrown ino the sea.” Next time I chant “From the river to the sea, Palestine will be free” at a protest, I plan to follow my friend Stanley Heller’s advice and add a clarifying second line, “From the river to the sea, justice and equality.”

7 For a theory of state capitalism, I recommend Wayne Price’s “The nature of the ‘communist’ states.”

8 Additionally, the PLO’s high-ranking Jewish official, Ilan Halevi, wrote a well-regarded monograph on Jewish history from ancient to modern times.

9 When anti-Zionist Jews have dared to criticize Miller’s scholarship as “embarrassingly conspiratorial” and mildly antisemitic, Miller’s supporters have denoucned even these anti-Zionist Jews as a “fake Left” and “scummy.”

10 As Rohini Hensman responds, “the remark shows little compassion for the Syrians being killed and driven out of their homes.”

11 For example, in a context of analyzing her own mixed ancestry, the Black-Jewish activist Jackie Walker irresponsibly wrote that Jews “were amongst ‘the chief financiers of the sugar and slave trade.’” A great overstatement, yes. But was it antisemitic as Randall asserts? In emphasizing its historical falsity, Randall cites a source which actually states the following: Jews’ role in the slave trade “was a considerable one during the formative years of the trade, in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries” before becoming very minor in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. Not mentioning that Walker is Black and Jewish, and not admitting that there was more than a kernel of truth to her overstatement, Randall fails to give Walker the nuance that he rightly requests be given toward Jewish Zionists.

12 Of course, many Zionists opposed these sentiments, going so far as to assassinate Kastner for example, and some Zionists herorically fought alongside anti-Zionist Jews in anti-Nazi revolts. Moreover, a discussion of Zionist antisemitism should be balanced by a recognition of pro-Nazi beliefs among many Palestinians historically, some 60 percent according to a 1941 Zionist intelligence brief.

For more on Zionist collusion with antisemitism, see Stanley Heller’s Zionist Betrayal of the Jews (SH Books, 2019), reviewed by Donna Joss for New Politics, and Lenni Brenner’s Zionism in the Age of the Dictators (OOOA, 2014), the 1984 edition available online from The Struggle. Although Brenner is sometimes portrayed as a paradigmatic Left antisemite, he in fact has spoken out strongly against antisemitism and was once enlisted by Edward Said to combat Holocaust denial in Arab societies. He was the one who first convinced me of the futility of the “Khazar hypothesis,” and he taught me the importance of acknowledging and condemning the antisemitism of Jerusalem’s Grand Mufti. He has publicly written strongly against the antisemitism of the Institute for Historical Research and Nation of Islam. It’s true that, due to his old-school Trotskyism, Brenner has used unacceptably pejorative language about communities he considered insufficiently “modern,” including those of his own former religion, orthodox Judaism, and also Arab peasants whom he alleges had a “low level of culture.” He has also made remarks to me that show he does not necessarily share my enthusiasm for the radical “resurgence” of Jewish and Native American traditions for anti-authoritarian purposes. Brenner’s unfortunate ultra-modernism is a product of his orthodox Trotskyism, and he is no more antisemitic than he is anti-Palestinian or anti-Indigenous.

13 Emphasizing capitalism’s abstract quality is not to ignore the role of state violence in creating and perpetually maintaining supposedly “free” markets. There are real people who authorize state violence to keep the system going, and it’s true that a significant minority of those people are Jewish. The problem is not who is in positions of state and corporate power; the problem is the system which allows those positions to exist.

14 There seems to be no well-known term for opposing U.S. nationalism, but I’m happy to identify as anti-Americanist in reference to the American Legion’s definition of “Americanism” as an unyielding loyalty to the U.S. government and its flag.

All the same, I wouldn’t call myself anti-American, since I have no interest in abolishing American culture which “race traitor” Noel Ignatiev described as “a mixture of the Yankee, the Indian, and the Negro (with a pinch of ethnic salt).”

15 I do think Waters has been given at least one too many chances by the Palestine solidarity movement. From his complaints about the “extraordinary power” of the “Jewish lobby,” to vilifying the Star of David, to appearing on Hamas television and using classic antisemitic tropes of a Jewish “puppetmaster.” This is all aside from his reactionary, campist politics on Syria.

16 Randall’s critique of BDS (121-126) does not engage the movement’s nuances such as its support for engaging Israeli individuals (distinct from Israeli institutions), its cooperation with progressive Jewish organizations worldwide, and its clear rejection of antisemitism.

17 Hechler authored The Restoration of the Jews to Palestine two years before Herzl’s The Jewish State. Hechler collaborated closely with Herzl, introducing him to dignitaries including German Emperor Wilhelm II and attending the First Zionist Congress. Historical preservationist Jerry Klinger describes Hechler as “the Christian minister who made Herzl and Political Zionism legitimate.”

18 This application of self-determination as stateless self-governance has parallels in Rojava’s “democratic confederalism,” although the movement’s upper levels have often failed to uphold their anti-authoritarian ideals. Democratic confederalism’s intellectual founder Abdullah Öcalan has expressed antisemitic ideas in his writing.

19 I added the U.S. section to Wikipedia’s page on the crime of apartheid. As of January 27, 2022, it is still on the page.

20 Palestinain Anarchist Budour Hassan’s “How the Syrian Revolution has Transformed Me” offers a beautiful vision of what such transnational solidarity can look like. I was heartbroken to see the BDS leadership pass on an opportunity, in June 2021, to voice solidarity with the people of Syria’s war-torn Idlib province.

21 I use the term “accomplices” with a nod to Indigenous Action’s essay, “Accomplices Not Allies: Abolish the Ally-Industrial Complex.”

22 An anti-Zionist reader of my draft rightly said that I was placing too heavy a burden on Palestinians. That’s all the more reason for external supporters to perform this heavy theoretical lifting. We should be very grateful that Palestinians themselves have already done essential theorizing on this matter, some of which I cite and link to in this review.

23 One Struggle morphed into Anarchists Against the Wall in the 2000s.

Leave a Reply