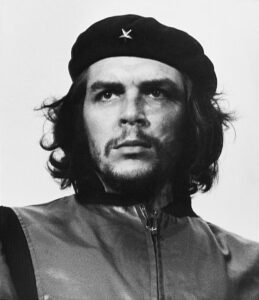

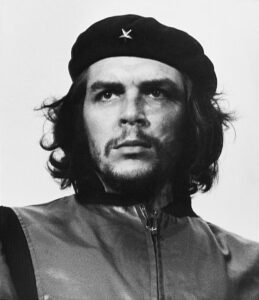

Janette Habel and Michael Löwy defend the political and intellectual legacy of Che Guevara as a Marxist, against Samuel Farber’s critique.

Janette Habel and Michael Löwy defend the political and intellectual legacy of Che Guevara as a Marxist, against Samuel Farber’s critique.

It is undeniabe that Luis Arce, the President of Bolivia, is no longer responding to the demands of his ex-boss, former President Evo Morales.

Extractivism is the only economic horizon of the Bolivian state, even as narratives shift depending on who is in power.

In October and November of 2019, clashes over the validity of presidential elections in Bolivia led to protests and the eventual ouster of the leftist Indigenous president Evo Morales, in what most observers characterized as a coup. In the year . . .

Bolivia has given the world an impressive lesson in democracy, but reactionary sectors of the country are once again revealing their anti-democratic impulse.

This exhaustion of signifiers is one of the characteristics of the political moment Bolivia is living, in which, apparently, everyone wants the same things, but conceives them in opposite ways.

Just weeks out from the October 18 elections, Bolivia’s coup government is again in crisis following the departure of three key ministers over an unconstitutional attempt to privatise an electricity company.

Latin America is experiencing an abrupt change generated by enormous confrontations between the dispossessed and the privileged. This confrontation includes both revolts by the people and reactions by the oppressors.

The October Revolts

The uprising in Chile is the most important event . . .

The coup d’état against Bolivian president Evo Morales has generated the kind of anguish that great defeats of revolutionary struggles evoke: Allende’s fall, Che’s death in combat, defeat in the Spanish Civil War. “Criticism is no passion of the head, . . .

As rightwing governments take power in Argentina, Brazil, and elsewhere across the region, Ecuador’s leftwing Alianza País (Country Alliance, AP) and Bolivia’s Movimiento al Socialismo (Movement Towards Socialism, MAS) and Bolivia have managed to hold onto power.

Bolivia received global attention for its anti-imperialist and anti-capitalist social movements in the twenty-first century. Best known perhaps were the Water Wars, against water privatization, in 2000 and the Gas Wars, demanding nationalization of the gas industry, in 2003. These rebellions entailed a radical rethinking of natural resource use and distribution.

Over the past two weeks, thousands of factory workers, miners, teachers, and health care providers have mobilized and blocked roads in La Paz and Bolivia’s other departmental capitals to protest the firing of 1,000 state textile workers. The workers were abruptly dismissed last month, when Bolivian President Evo Morales announced the closure of Enatex, the state-run textile company.

This article is based on a talk given at the Left Forum in New York City, May 21, 2016.

Evo Morales’ government has suffered two significant electoral setbacks in the past year and is currently mired in scandal, which has put its long term projections – planned for up to 2025 – into question. Why is one of the America’s most progressive government’s stumbling at this juncture?

This remarkable piece of militant history, based on interviews, as well as leaflets, letters, manifestos, dug out of public archives and private collections, from the heights of La Paz to the outskirts of Paris, deals with the Bolivian labor movement, the most persistent and combative in the Western Hemisphere. Bolivia is one of the very poorest countries of the Americas, and also the most Indian: 2/3 of the population describes itself as indigenous.

A NEW ALLIANCE OF DEMOCRATICALLY-ELECTED GOVERNMENTS with a range of socialist programs is sweeping Latin America. New trade agreements that embrace the possibility of pan-regional alliances are being forged. Venezuela, Ecuador, and to a significant extent Argentina, Chile, Nicaragua, and Brazil articulate some policies of uplifting the poor and challenging US and neoliberal hegemony. Other nations are making their way to this list. Among these synergistic movements, no country in Latin America is better positioned to become a democratic socialist state than Bolivia.