[Editors’ note: We are posting two articles on the 2020 U.S. presidential election from the forthcoming Winter 2021 issue of New Politics. Subscribe now to get first access, in print or digitally, to the rest of the issue with original analysis of American politics, the crisis and resistance in global capitalism, the Left in Latin America, Belarus, union democracy, community schools, the ecological situation in China, and much more.]

[Editors’ note: We are posting two articles on the 2020 U.S. presidential election from the forthcoming Winter 2021 issue of New Politics. Subscribe now to get first access, in print or digitally, to the rest of the issue with original analysis of American politics, the crisis and resistance in global capitalism, the Left in Latin America, Belarus, union democracy, community schools, the ecological situation in China, and much more.]

[This article will appear in the Winter 2021 print edition of New Politics under the title, “Biden Replaces Trump: A Malignant ‘Normalcy’ is Restored” We re-post it on the website with a new title that highlights its arguments for making a “clean break” with the Democrats and building a new party and movement of the left in the immediate, not the distant, future. We invite responses.]

The defeat of Donald Trump came as a deliverance to millions of Americans after four years of political hell. It was greeted by mass spontaneous outbursts of joy and relief. Ridding ourselves of a uniquely malicious and bizarre president is reason to celebrate, but I argue that it is misleading to see the election as a victory of democracy over authoritarianism. Biden’s win is the triumph not of democracy but of an oligarchic status quo, itself an increasingly authoritarian system. And I suggest that the conclusions to be drawn from the election point toward a different perspective going forward for the left.

Even though Biden won by more than six million votes, the 2020 election, Naomi Klein observed, “should have been a repeat of Herbert Hoover’s loss in 1932. We are in the grips of a pandemic, a desperate economic depression, and Trump has done absolutely everything wrong” (The Guardian, Nov. 8, 2020). In those working-class rust belt counties in the Midwest where Biden won, his margin of victory was razor thin, and nationally Trump won the votes of 40 percent of union members. He did manage to take Ohio and came close to winning Pennsylvania, Wisconsin, and Michigan. Exit polls showed that a plurality of voters saw the economy as the main issue; Trump won 82 percent of this group. Biden made the election a referendum on Trump’s character, and especially on his handling of the pandemic, but without offering a plan to sustain incomes and small businesses until COVID is defeated. Workers felt forced to choose between risking their health or facing economic disaster, which is one reason so many of them voted for the incumbent, who constantly called for “opening up” the economy. Biden’s vague, minimalist, cliché-filled campaign—promising to “heal the soul of the nation” (code for bipartisanship)—inspired little enthusiasm. The Democratic platform actually referred to housing as a right and promised “fundamental reforms” to address “structural and systemic racism” and “entrenched income inequality.” Biden scarcely even mentioned them in the campaign, and it is safe to predict that an austerity-minded administration and mainstream Democrats in Congress will do virtually nothing to fulfill these promises.

The threat of a coup, not totally baseless but wildly exaggerated, was emphasized by liberal pundits—but also by a great many leftists—to frighten voters into turning out for Biden. Aside from a few instances, far-right thugs did not disrupt voting. More serious were the threats to mail-in balloting. Under Trump’s Postmaster General Louis DeJoy, postal delivery was slowed down and mail sorting machines were removed or destroyed. Republican governors and state legislatures have made determined efforts in recent years to suppress voting numbers in minority neighborhoods, for example by closing polling places and purging voter lists, but these were not enough to alter the result. Now, however, millions of Trump supporters believe they have been the victims of a gigantic fraud, and this has ominous implication for politics in the coming period.

Trumpism Marches On

Trump may be out of office, but Trumpism—white nationalism, misogyny, conspiracism and paranoia, murderous hatred of “socialism,” and longing for a dictator—will be a powerful force after Biden takes office. A huge mass of right-wingers has always existed in the United States, of course, but in recent years, despair caused by the extreme deprivations of neoliberalism has galvanized them like never before, and since 2016 Trump has provided an icon around which they have rallied and proliferated. Trump himself, even assuming he continues to exert cult-like dominance over these forces, has no consistent ideology, let alone the totalist ideology of a fascist leader. Indeed he lacks the intellectual ability, or the mental discipline, to formulate a coherent program. In the absence of an ideology, Trump’s worshipful followers identify passionately with him personally and with his narrative: that America was once “great,” when white men exercised unchallenged dominance, and that only he, as a strongman and a “very stable genius,” has the power to “Make America Great Again.” The psychiatrist Robert Jay Lifton prefers the term “solipsism” rather than “narcissism” to describe Trump’s psychology. He defines solipsism as “a cognitive process of interpreting the world exclusively through the experience and needs of the self” (Robert Jay Lifton, “The Assault on Reality,” Dissent, April 10, 2018).

The malevolent forces that identified with Trump’s solipsistic reality constitute, in Lifton’s words, “a major segment of our society [that] ignores or defies the principles of reason, evidence, and shared knowledge that are required for the function of a democracy.” The elections were rigged, they insist, the pandemic is a hoax, leading Democrats are running a massive ring of Satanist pedophiles devoted to the abduction, trafficking, torture, sexual abuse, and cannibalizing of children.

A significant part of Trump’s following are Christian nationalists who consider him to be another King Cyrus, the Persian ruler who, though a pagan, acted as an instrument of God’s will when he freed the Jews from Babylonian captivity, according to the Book of Isaiah. Trump too, is a sort of pagan, hardly a proper Christian in any case, but God works in mysterious ways, and he has chosen a powerful instrument to rescue his people from the wicked and ungodly, with their abortions, homosexuality, feminism, and so on. Christian nationalists are thoroughly patriarchal and authoritarian, and they long for Trump to be an autocrat, like King Cyrus.

This gift from God is, of course, utterly amoral. He emerged from the 1980s cesspool of New York City’s leading politicians, gangsters, and business people, especially real estate developers, most of them habitués of the disco Studio 54. (Frank Rich, “The Original Donald Trump,” New York, April 30-May 13, 2018, is a superb description of this slimy milieu.) It was a bipartisan but overwhelmingly Democratic crowd. One of the presiding deities was the notorious lawyer and power broker Roy Cohn, former chief counsel for Joe McCarthy, Trump’s personal mentor and a creature described in Tony Kushner’s Angels in America as “the pole star of human evil.” It was from Cohn that Trump learned always when challenged to counterattack viciously and deny everything. In those days, Trump was treated as an entertaining con man—“The Donald,” as he was routinely known in the tabloid press.

Trump is an extreme example of the authoritarian personality, obsessed with control and obedience, filled with delusions of grandeur and almost limitless pathological aggression. His self, structured around a core of malice, is an “evil self,” and he is able to attract masses of mesmerized admirers to his narratives of blame and fantasies of revenge. Biden, on the other hand, is not a frenzied demagogue. But he is nevertheless a different kind of evil self, one that fetishizes order and stability, which always take precedence over justice and humanity. If a U.S.-dominated world order requires the deaths of hundreds of thousands of Iraqis, then so be it. (For an analysis of both kinds of evil selves, see Barry Magid, “The Evil Self,” Dynamic Psychotherapy, Fall/Winter 1988. Magid’s examples are Hitler and Kissinger.)

As long as neoliberals like Biden offer no solution to social crises and their only clear opposition is the far right, Trumpism will flourish and expand. Moreover, unless an independent left takes the field, the far right—increasingly coterminous with the Republican Party—will attract more and more working-class support. And out of the far right, the elements of outright armed fascism, as yet disorganized, amorphous, and numerically puny, will soon coalesce and take to the streets in force. Murderous white nationalist groups have already deeply infiltrated police forces around the country.

That 72 million people voted for Trump, more than in 2016, and that he won white voters by 15 points, nearly as many as in 2016, and even made inroads among Black men and Latinx voters, are dreadful facts. But at the same time poll results show strong majority support for progressive policies like Medicare for All, heavily taxing the rich, and massive government stimulus programs. This contradictory picture is the result of the fact that the left, unlike the right, has no political party of its own to shape public opinion, no party that could decouple bigotry from hatred of the establishment and persuade voters that major reforms are achievable.

To change public opinion, the left has mass mobilizations. Occupy Wall Street, the first wave of Black Lives Matter (BLM) protests, the Women’s March, the teachers strikes, and above all the immense upsurge following George Floyd’s murder, have enormously heightened popular consciousness of racism, sexism, inequality, and austerity. The problem, however, is that after the mobilizations flare up, they eventually die down, and politicians go back to business as usual. Protest is essential, but it is not enough. People must be able to envision a political way forward. In the absence of third-party initiatives, defunding demands, despite their popularity in certain cities, are unlikely to succeed. Even where Democratic city councils seemed to adopt major reforms in policing, as in Minneapolis, these have been quickly cancelled. To survive and grow, a third-party breakthrough would have to be buoyed by a social upsurge, but it is equally true that no social upsurge would be sustainable without an electoral breakthrough.

In a New York Times op-ed (Oct. 21, 2019), Michelle Goldberg noted that, after 2017, “as Donald Trump’s sneering lawlessness and stupefying corruption continues to escalate, it’s confounding, to say the least, that Americans aren’t taking to the streets en masse.” Following the huge protests that were a response to the 2016 election, mass demonstrations began to fade out, even as Americans’ outrage and loathing increased. Goldberg reminded us that “Lyndon Johnson was famously tormented by protest chants that could be heard through the walls of the White House,” and she asked, “Why isn’t Trump?” Why wasn’t Trump, like LBJ, met with militant protests wherever he went?

It was a good question. The resistance included the spontaneous demonstrations at airports against the Muslim ban and at immigration detention centers against family separation and children in cages, but mostly people seemed to accept the Democrats’ insistence that the only realistic form of resistance was “voting blue.” Then, however, seven months after Goldberg’s article, came the police killing of George Floyd and the explosion of massive multiracial protests led by BLM. An estimated 26 million people demonstrated in two thousand locations in the United States. Eventually, angry chants were discernible through the White House walls.

Still, during most of the Trump years, the organized left, embodied mainly in Democratic Socialists of America (DSA), immersed itself in the Democratic primary process rather than building a real opposition at a time of maximum anger and disgust. It was a bad choice. Electing a handful of individuals to Congress who call themselves democratic socialists, and a somewhat larger number to state and local government, has put a few good people in office, but it has done nothing to build an independent movement. The Squad’s constituents vote for them not because they’re socialists, but because they’re more progressive Democrats than their primary opponents.

In fact, efforts to build a strong movement against corporate neoliberalism have been hobbled by Bernie Sanders’ insider strategy. David Sirota, one of Sanders’ senior advisers in 2019, reported that he and other advisers pushed Sanders to highlight his differences with Biden. But except for some moments in Iowa and once in the last debate, on Social Security, he didn’t (“The Tyranny of Decorum Hurt Bernie Sanders’s 2020 Prospects” Jacobin, April 16, 2020). As a result, Biden never had to defend his appalling record and could harp instead on his “electability”—an argument most Democratic primary voters in the South and Midwest accepted, even when they supported key parts of Sanders’ program. Never, or hardly ever, mentioned by Sanders were Biden’s role in helping Republicans pass the Iraq War resolution and the 2005 bankruptcy bill, killing initiatives to lower the price of prescription drugs and prevent profiteering on vaccines developed at taxpayer expense, his refusal as chair of the Senate Judiciary Committee to seriously investigate sexual harassment charges by Anita Hill and other women against Clarence Thomas, his pathological lying, and more. And of course, as soon as Biden won the nomination, Sanders became a “good soldier,” suppressing all criticism in the interests of party unity.

“Normalcy”

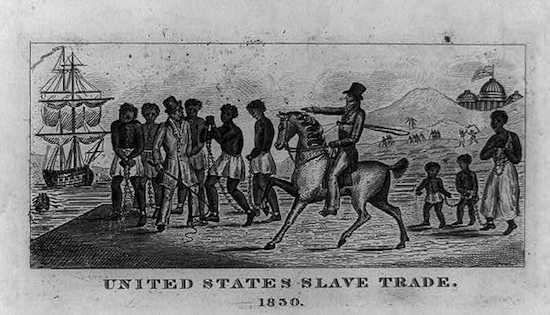

Biden stands for a restoration of the pre-Trump status quo. While millions, traumatized for four seemingly endless years by a demented goblin, long for what they consider “normalcy,” it is worth remembering what “normal” conditions have been for at least the past thirty years, 16 of them under Democratic administrations: profound systemic racism, a cruel immigration policy, de facto school segregation, increasingly unaffordable housing, a brutal upward concentration of wealth, prisons full to bursting, rampant police violence, war after war, and, worst of all, a world hurtling toward climate catastrophe. On all of these issues, the Trump administration represented, to a great extent, continuity rather than rupture. For example, police killings amounted to about one thousand per year under both Obama and Trump. The Obama administration deported three million people and militarized the border. Its environmental initiatives—fuel efficiency standards, carbon taxes, tax credits for solar panels, joining the Paris Agreement—were far outweighed by a massive increase in oil and gas production and export, the expansion of fracking and offshore drilling, and the laying of tens of thousands of miles of new pipelines. Trump’s dangerous environmental policies, his vicious treatment of migrants and asylum seekers, his encouragement of police violence, all built on the Obama-Biden legacy.

Trump’s open contempt for democracy and affinity for authoritarian leaders such as Putin, Erdogan, Modi, Duterte, Mohammed bin Salman—even at times Kim Jong-un and Xi Jinping—were shocking and sinister. But his policies did not differ radically from those of his predecessors. Even Obama supported anti-democratic coups in Egypt and Honduras and prosecuted whistleblowers under the infamous 1917 Espionage Act. For about a century, we have not seen a president who openly espoused white supremacy and promoted vigilantism. Woodrow Wilson supported the Ku Klux Klan and made no attempt to disguise his racism, but no other president between Wilson and Trump has so shamelessly exhibited outright bigotry. Trump is certainly uniquely evil, but in a certain way “abnormalizing” him, to use Samuel Moyn’s expression (“The Trouble With Comparisons,” New York Review Daily, May 19, 2020), has served to conceal the continuity of American governance, especially in recent times—and to prepare Americans to accept the return of “normal” neoliberal and imperialist brutality under Biden and Harris.

Far from strongly opposing Trumpism, the Democrats have been its enablers. The government spending bill that sailed through Congress at the end of 2019, with the votes of 150 out of 232 Democrats, included funding for the Department of Homeland Security and the border wall, with no restriction on the migrant detention policy. At least the bill’s Democratic supporters could use the excuse that it was a budget that contained necessary items and that passing it was the only alternative to another government shutdown. But there could be no extenuating circumstances to justify Democrats’ support for colossal military spending. Trump’s record-breaking military budget—with Congress actually allocating more than he had asked for—was passed in 2019 with the votes of 180 House Democrats, while in the Senate only four Democrats voted against it, as did an equal number of Republicans.

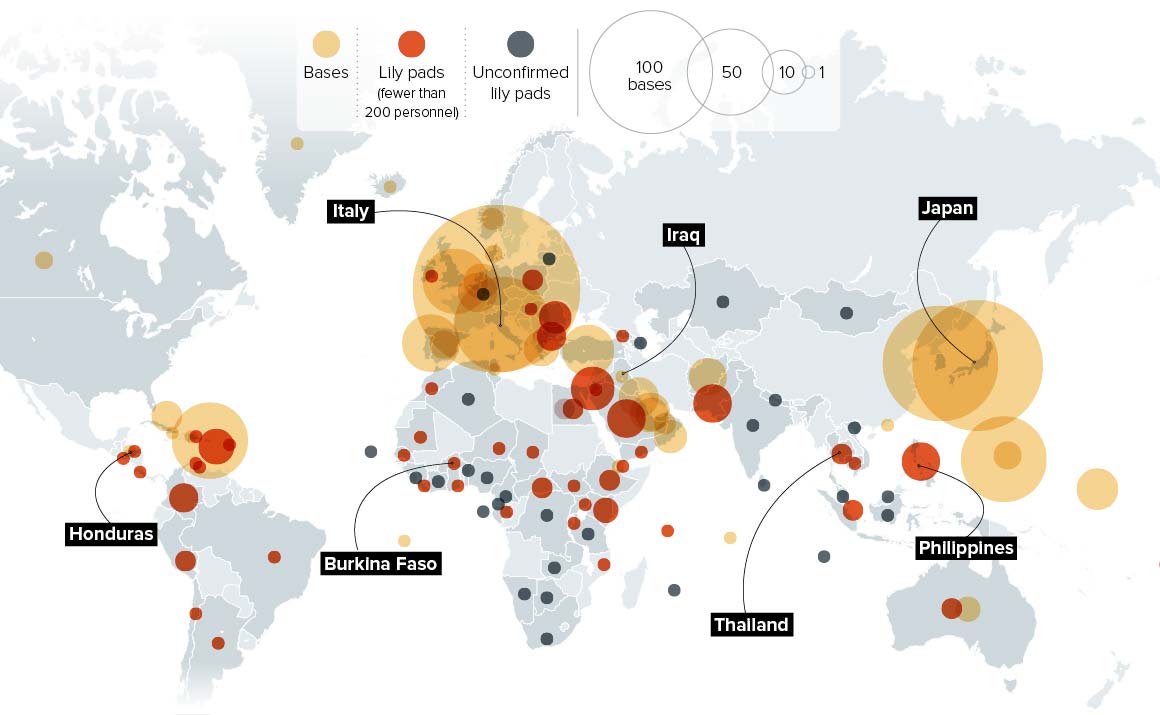

Democrats objected to Trump not because he’s an imperialist, but because he’s an extraordinarily amateurish and unstable imperialist, one who acts with mindless abandon and dispenses with the ideological niceties. The Democrats and the foreign policy establishment clashed with Trump over multilateral agreements on trade and the environment, relations with NATO, and his withdrawal of troops from Syria. But since World War II, the U.S. empire itself has been a touchstone of bipartisanship. No Democratic leader would consider dismantling it. On this question, there is no disagreement between the two parties: The United States must continue to be the dominant superpower, policing the world allegedly in the interest of order and stability, but actually on behalf of a cruel status quo that condemns billions to misery and early death. Its monstrous military establishment must continue to be funded lavishly, at the expense of social programs.

On foreign policy, even Bernie Sanders’ record in Congress has been highly equivocal. He supported the congressional resolution giving George W. Bush a blank check to wage war in the aftermath of 9/11. He voted in favor of appropriation bills to finance the U.S. occupation of Afghanistan and Iraq. In 2006, Sanders voted for a House resolution giving support to Israel’s war on Lebanon and also to impose sanctions on the Palestinian Authority.

As for Biden, he has made it clear that his foreign policy will be another exercise in “normalcy”—restoring the global power that this country has exercised since World War II, winning back the respect of U.S. allies that Trump alienated—as well as getting tough on China and thus initiating a new Cold War.

And it is important to recall the foreign policy crimes of the pre-Trump era, among them the invasion and devastation of Afghanistan and Iraq; wars in Serbia, Libya, and Yemen; the program of “rendition” (kidnapping) and torture; Guantanamo and Bagram; the slaughter of thousands of innocents by drones and fighter jets. None of the crimes committed by Trump outside U.S. borders were worse than these “normal” offenses. In fact, it can be argued that the violence and lawlessness of Bush and Obama were actually worse.

Biden has promised to reestablish Washington’s “global leadership,” a euphemism for imperial hegemony. Neocon veterans of the Bush-Cheney years, Eliot Cohen and Eric Edelman, have predicted that Biden will be hawkish on Iran. And if the Democrats take control of the Senate, the majority leader will be Chuck Schumer, who opposed the Iran deal. Cohen says that he and Edelman feel “very comfortable” with Biden’s commitment to Israel (Mondoweiss, Oct. 29, 2020). This too is what is meant by returning to “normal.”

The Democrats Are Unchangeable

Speaking on “Democracy Now” (April 10, 2020), Noam Chomsky said, “With a Biden presidency, there would be, if not a strongly sympathetic administration, at least one that can be reached, can be pressured. … Biden [is] … kind of a pretty empty—you can push him one way or another.” The idea of Biden as a sort of empty vessel is not credible. He is a thoroughly corporate creature whose whole career has been bankrolled by the credit card industry and by other major companies chartered in Delaware, like DuPont. Wall Street knew what it was doing when it heavily backed his presidential campaign. In a remark that distills the essence of Biden’s politics, he promised his wealthy funders that nothing would change for them under his presidency.

A hardened neoliberal and ardent supporter of U.S. global power, deeply embedded among the ruling elites, whose interests he has spent a lifetime serving, can he nonetheless be pushed to initiate programs that at least go part way toward addressing the alarming crises now upon us? Confronted by massive pressure from below, comparable to the social unrest and the industrial union movement of the 1930s and to the Civil Rights Movement, ghetto uprisings, and anti-war demonstrations of the 1960s, or by another social explosion like the one that occurred in the spring and summer of 2020, Biden might be forced to make concessions. But we should not count on it. As a lifelong partisan of austerity and deficit reduction, he would have to do a complete about-face to support the massive public investment and income support needed to address the economic crisis.

And even if Biden is pushed by mass upheaval to support programs that are outside his neoliberal comfort zone, they will be as stingy and as nonthreatening to the profit system as possible. These are desperate times, and they call for radical measures. Medicare for All is the only rational, humane way to deal with COVID and inevitable future pandemics. But in the unlikely event that Congress passes Medicare for All—unlikely because the overwhelming majority of Democratic members of Congress are themselves committed to preserving the private insurance industry—Biden has promised to veto it. In the first debate, he forthrightly declared, “I support private insurance.” But worse than that, he has even distanced himself from a universally available public option, which is itself a conservative substitute for Medicare for All, designed to preserve the employer-based health insurance system. Massive unemployment in the current and deepening depression has already left millions without the private health insurance that came with their jobs and will do the same to millions more. Biden’s idea of a “public option” is limited to low-income Americans who qualify for Medicaid but live in the 14 Republican-controlled states that have refused to accept the expansion of Medicaid coverage passed by Congress in 2019. So Biden’s paltry public option would still exclude the vast majority.

During the primaries, almost all the Democratic contenders paid lip service to some version of a “Green New Deal” (after Nancy Pelosi sneeringly dismissed it as the “green dream or whatever they call it”). But only Sanders defined it as a comprehensive anti-corporate plan to stop fossil fuel production and promote renewable energy and mass transit, with job guarantees so that workers are not forced to choose between environmentally destructive jobs in coal, oil, fracking, and so on—and unemployment. In view of what is at stake—the UN Climate Report gives us only ten years to make the changes that may prevent ecological catastrophe—the planet’s survival depends on a bold, radical program.

For Sanders and the Squad, a stubborn commitment to working within the Democratic Party and the concomitant pressure to get along with the Democratic leadership constantly undermines their effectiveness in challenging the neoliberal center. When right after entering the House, Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez joined a sit-in by the Sunrise Movement in Nancy Pelosi’s office, Pelosi’s chief of staff declared, “We support every single thing they’re protesting us for.” AOC responded, “That is absolutely true. … What this just needs to do is create a momentum and an energy to make sure it becomes a priority for leadership.” The idea that establishment Democrats actually support radical reforms but simply refuse to prioritize them is false and disorients the left. Sanders, after losing his campaign for the nomination, not only supported Biden as the only alternative to Trump, but predicted that Biden will be the “most progressive president since FDR.” Once Biden reemphasized his opposition to Sanders’ main policy proposals—Medicare for All, the Green New Deal, defunding the police—Sanders was forced to shift from making ridiculous prophecies to pleading with left-wing Democrats to “make sure Biden becomes the most progressive president.” The former vice president was urged to move left in order to “make a stronger outreach to young people, the Latino community, and the progressive movement” as a means of strengthening his campaign—advice that, it goes without saying, Biden firmly rejected.

Even after the enormous and inspiring Sanders insurgency, the Democratic Party remains largely unchanged. Pelosi, Schumer, and now Biden are still firmly in charge. As a result of the efforts of Justice Democrats and Our Revolution—organizations launched by leaders of the Sanders campaign and dedicated to transforming the Democratic Party and electing progressive Democrats to office—the party’s left wing has grown slightly. It is a small but significant presence in a few state legislatures and city councils, especially Chicago’s. But at the national level the Democratic Party’s left is still minuscule, marginalized, and powerless, despite AOC’s media publicity. There are only ten House members who were endorsed by Justice Democrats. The 60 seconds given to Ocasio-Cortez at the Democratic National Convention, combined with the attention lavished on Republican speakers, showed how committed the party leadership is to centrism and compromise, without any real concessions to the left. In the House, the largest ideological group by far calls itself the New Democrat Coalition, with about half the members of the Democratic caucus. Founded in 1997 as an affiliate of the pro-business Democratic Leadership Council, its priorities are “economic growth” and “fiscal responsibility.” In an op-ed devoted to the New Democrat Coalition, entitled “No, the Democrats Haven’t Gone Over the Edge” (New York Times, Sept. 17, 2020), conservative columnist David Brooks assured his readers that the party contains “a large, strong center that will keep it in the political mainstream.”

A New Party: Now Is the Time

What if Sanders had chosen to run an independent campaign in 2016? Of course, he would have won far fewer votes. But his votes as an independent would still have numbered in the millions, and he might at least have begun a left electoral alternative to the Democrats. Had Sanders and his supporters broken in 2016, we might have seen the birth of a combative third party, leading mass demonstrations, protesting and disrupting the atrocities of ICE and the Border Patrol—a real opposition instead of the passive and ineffectual “resistance” of the Democrats. And indeed, the Democrats, faced with a rival on their left flank, would have felt real pressure to stand up more decisively to Trump.

Canvassing for Sanders and other Democratic candidates by DSA and others on the left has diverted energy and resources that could have been used to build a powerful mass movement of protest and disruption aimed at Trump and the Republicans—and also at their Democratic abettors. And running candidates in Democratic primaries continues to reinforce loyalty to the Democratic Party and to the established prejudice that the Democrats are the only viable alternative to the right.

If the organized left is to lead a response both to the new administration and to an increasingly authoritarian and right-wing Republican Party, as well as to fascists, then socialists, especially the reported 85,000 members of DSA, could play a key role. Optimally, building a third party of the left should become DSA’s top priority. Now that Trump has been defeated, and there is less of a perceived imperative to rally behind the Democrats as the only bulwark against the right, it may be possible to convince many socialists to become third-party advocates and builders.

While most of the caucuses in DSA claim to be in favor of an independent workers party eventually, that prospect keeps being deferred to an ever more distant future. And meanwhile, most of the organization is steadily sucked into the Democratic Party, becoming just another part of its powerless left wing—recreating the old realignment program of DSA’s earlier incarnation, in which socialists saw themselves frankly as junior, subordinate partners in coalition with liberals. Among the broad left, most of the current discussion is about how to improve work within the Democratic Party, mainly by persuading the “centrist” leadership that they can win with a progressive program (“centrism” is itself a cozy-sounding misnomer, suggesting moderation and caution, instead of mainline Democrats’ steely corporate neoliberalism).

Until recently, the most influential perspective within DSA has been the “dirty break,” first laid out by Seth Ackerman’s “Blueprint for a New Party,” published in 2016 in Jacobin. Ackerman called for DSA to start building a pre-party within the existing Democratic Party, essentially a new party but without a ballot line. “Rather than yet another suicidal frontal assault,” he argued, “we need to mount the electoral equivalent of a guerilla insurgency.” Rightly deploring the strategy of working to elect individual progressives who create a base rather than a structure to which they’re accountable, Ackerman envisioned a national organization with chapters at the state and local level, a binding program and electoral candidates chosen by the membership. Its members and candidates would refrain from promoting the Democratic Party or taking posts in its apparatus and explicitly renounce the goal of reforming the party. They would refuse to endorse centrist Democrats. And all this while continuing to contest Democratic primaries and running as Democrats in general elections.

How such an organization could persuade voters to support its candidates on the Democratic ballot line while totally repudiating the Democratic Party remained an unresolved contradiction, however. And, as argued below, the goal of a mass socialist rather than a broader radical party is unrealistic under current circumstances. In any case, as the dominant politics within DSA moves away from the dirty break perspective toward a de facto realignment position, there are so far no signs that this pre-party will materialize. Instead, the dirty break has become a cover for indefinitely continuing to function as a left-wing pressure group within the Democratic Party. DSA strongly identifies with candidates and elected officials who explicitly or tacitly support realignment—a better name for it would be “boring from within”—and reject any kind of break, clean or dirty.

What about the Greens? Howie Hawkins and Angela Walker ran an honorable ecosocialist campaign, and their message of independence from the Democrats was loud and clear. I was proud to vote for them, but I knew it was a protest vote and nothing more. Dirty tricks by the Democrats kept the Green Party off the ballot in many states, but even without such maneuvers, the panic and loathing inspired by Trump would have driven most potential Green voters into the Biden camp. More importantly for the immediate future, it is highly unlikely that the Green Party has the potential simply to grow, through slow accretion and without significant institutional support, into the mass party that we need, one that can really contend for power on a national scale. To bring that into being, there must be a political campaign within the labor movement and within BLM and the environmentalist, women’s, civil rights, and LGBTQ movements. Out of these movements can come the needed critical mass. Labor in particular can contribute serious numbers and resources.

But I want to argue that we should not wait for this fight to begin. Large numbers of progressives will break from the Democrats only when there is already a new party, standing for a clean break and much bigger than the Greens, for them to gravitate toward. It is the job of those who understand that operating within the Democratic Party is a dead end, and who have abandoned lesser-evilism, to start building that new party now.

Launching a new party would not require massive forces. A little over 50 years ago, a remarkably successful attempt was made by a few hundred radicals in California. A small minority within the Community for New Politics—a semi-independent group spawned by the anti-war congressional campaign of Democrat Robert Scheer—led by members of the Independent Socialist Clubs, re-registered 105,000 voters, almost twice as many as the law required, into a new Peace and Freedom Party (PFP). PFP was organized around a program of immediate withdrawal from Vietnam and support for the Black Liberation movement. Soon after PFP qualified for ballot status in January 1968, however, the entry of Eugene McCarthy and Robert Kennedy into the race for the Democratic presidential nomination heavily dampened the growing enthusiasm for a new party and drew most third-party supporters back to the Democrats. Already, the year before, chances for a strong anti-war ticket had been dashed when Martin Luther King Jr. and noted pediatrician Benjamin Spock turned down a growing movement to have them run for president and vice president, although both had seriously considered it. Still, when the nomination of the pro-war Hubert Humphrey at the Democratic National Convention drove masses of McCarthy and Kennedy supporters right back out, PFP might yet have attracted larger numbers of disaffected Democrats had it made itself into an organizing center for a radical left with broad appeal. Instead, PFP made the mistake of nominating Black Panther Party leader Eldridge Cleaver, who preferred an alliance with the Youth International Party, known as Yippies, and their leader Jerry Rubin, who was addicted to pranks and street theater. Their campaign was an unappealing combination of ultra-revolutionary rhetoric and farce—Election Day was proclaimed “erection day.” So it was not independent political action itself, but the particular form it took that doomed third-party efforts in 1968.

The base for a new party already exists: disillusioned Sanders, and even many Warren, supporters (more than 12 million voted for Sanders and Warren), BLM demonstrators, militant teachers and health care workers. Opportunities would seem to be especially promising in the cities, in most of which Democratic rule has been palpably dysfunctional yet unchallenged from the left, where mayors and city councils flagrantly promote the interests of finance and real estate. Suffering from massive poverty, exorbitant housing costs, and decaying social services, most non-elite urban voters tend to be deeply alienated from local political contests. Turnout in New York City was only 24 percent in 2013, when de Blasio was first elected mayor. There is thus good reason to believe in the potential for mass mobilization around a program of large-scale direct investment in housing, education, health care, and job creation through public works, financed by steep taxes on wealth—even though there are severe legal limits on the power of municipal governments to implement such policies. One area where cities do have the authority to make major changes is police funding. A third-party-led campaign to defund police departments should have particular resonance in Democratic-run cities, such as Chicago, Minneapolis, New York, Seattle, and many others, that have witnessed extreme police brutality.

A new party must appeal to the widest constituency with a broad radical program. A great many on the left have an unrealistic idea of the extent to which Americans today embrace socialism. Certainly, polls show there are far more who consider themselves socialists or “approve” of socialism than at any time since the 1930s. DSA is now, perhaps, large enough to form a democratic socialist party—but not as an alternative to a broader, radical, workers or people’s party. What most Americans understand by “socialism” is essentially a revived New Deal-style left liberalism, as championed by Bernie Sanders, but this represents today a sharp challenge to the capitalist system. Most of those who could be attracted to an independent party of the left are just beginning to reject establishment politics and are not yet prepared to identify themselves as socialists. But they can be won to a fight for radical reforms, such as the Green New Deal; in the course of those fights we should have confidence that they will learn that capitalism as a social system is the enemy and must be destroyed root and branch.

Because Trump-style right-wing populism has succeeded in posing as an alternative to the status quo, it can be countered only by a genuine, radical-democratic alternative, one that attacks capitalists rather than people of color, immigrants, and queer folk. The bulk of a new party’s supporters would undoubtedly come from the Democrats’ voting base, but it will be necessary—and possible—to attract many workers and nonvoters who are currently pro-Trump. An anti-corporate, anti-elite political movement has the potential to win workers and others away from their racism and xenophobia by engaging them in common struggle with immigrants and people of color against the oligarchy that oppresses all of them.

There was always an independent logic implicit in the Sanders campaign, and now it has to be made explicit. However, a broad left party would have to be organized in an entirely different way. The Sanders “movement” was never an authentic movement, but rather a traditional electoral campaign, albeit one with a huge base of active, enthusiastic supporters—but still, a campaign over which Sanders had absolute control, and which was instantly dissolved prior to the Democratic Convention. A new party, by contrast, would have a formal membership democratically deciding on candidates, program, and strategy.

In terms of its politics, this new party would be in many ways a continuation of the Bernie Sanders campaign but with one crucial difference: It would abandon the notion that the Democrats are either some sort of workers party that has gone astray or basically an electoral convenience, a mere ballot line for progressive candidates—rather than an intrinsically pro-corporate, anti-progressive opposing force. To be consistent, a conscious decision to break with the Democrats should entail political hostility to the Democratic Party, not merely its leadership, regarding it as an enemy, not a misguided, potentially progressive party that has temporarily “lost its soul.”

A new party could be built initially around a few key issues, starting with Medicare for All and the Green New Deal, stopping police violence against Black people, and a major investment of resources to fight the coronavirus. It should embrace the Breathe Act, a bill championed by Ayanna Pressley and Rashida Tlaib to divest from policing and invest in alternative, community-based approaches to public safety. It might call for public ownership of the energy and financial industries—but even if it didn’t, this agenda would require a full-scale assault on the health insurance and fossil fuel industries and full employment through a massive public works program. Other positions ought to include substantial cuts in the military budget, nuclear disarmament, a noninterventionist and pro-democracy foreign policy. A domestic pro-democracy agenda would call for reforming the electoral system through legislation to make voting rights consistent and enforceable throughout the country, introducing proportional representation, abolishing the Electoral College, and stripping the egregiously anti-democratic Supreme Court of its power to overturn legislation. Contrary to popular belief, disempowering the Supreme Court would not require a constitutional amendment but could be achieved by Congress.

All of this would mean that the party, while not socialist, would stand in clear opposition to the power of the corporate oligarchy and to the two parties that serve its agenda. It would be committed to working people and the fight against all forms of oppression.

Electoralism and Movement-Building

The new party would be a party of social movements, with members drawn from the Black, Latinx, environmental, women’s, immigrant rights, and LGBTQ movements, as well as a strong anti-fascist movement that will need to be mobilized without delay. Bernie Sanders provided support to social movements, but he did not represent them. A new party, on the other hand, would function as an extension of mass struggles, not an electoral alternative to them. It would see its job as escalating and intensifying social movements, not drawing them off the streets and into the polling places. It could tie those movements together and provide them with a continuous national political voice, enabling them to act not as separate pressure groups, but to combine their forces in a struggle for political power. In fact, it should not be a primarily electoral vehicle, but rather use elections as one important arena for raising consciousness and building a political movement, rather than putting people in office. In reaction against the kind of electoralism practiced by DSA, which prioritizes get-out-the-vote efforts on behalf of self-appointed socialist office seekers running as Democrats, some leftists have counterposed electoral activity to movement-building. But a kind of “electoralism from below” as outlined here would have a complementary, mutually reinforcing relationship with movement-building.

While contesting elections at all levels, a new party must avoid any unrealistic expectations of winning in the short run. It will need to build toward running a candidate for president in 2024, but with the understanding that even if the party’s candidate were to win only 10 percent of the vote, that would be a major breakthrough. It would represent millions making the extremely difficult decision to abandon their illusions in the Democrats and opt for a genuine alternative.

Given the ferocity of the deepening economic crisis and the inevitably feeble and pro-corporate response of the Biden administration, a new party, once initiated, might grow very quickly. To do so, though, it would have to overcome the crippling fear of the “spoiler effect.” To grow it would have to peel people away from the Democratic Party as well as mobilize independents and nonvoters. And since this would weaken mainly the Democrats, it might give a temporary electoral advantage to the Republicans. Especially in swing states, the risk of spoiling elections for the Democrats is obviously great, but a serious third-party effort could not for that reason forego organizing throughout much of the Midwest. Anything less than consistency would fatally compromise the new party’s independence because it would be saying, in effect, that independence only matters when it does not hurt the Democrats.

It could not be a labor party, a party of the organized labor movement. The union leadership, with only a few exceptions, is still too cautious and conservative to break with the Democrats. But it would draw supporters from unions, especially ones with militant locals, like the teachers and health care workers. It should, however, declare itself in favor of a labor-based party, urging the unions to break with the Democrats. And, of course, it would act aggressively in support of strikes and other worker struggles. In these ways it could act as a catalyst, pointing the way toward political independence for the labor movement as a whole.

It would stand for thoroughgoing and consistent democracy, at home and abroad. And it would stand against all forms of authoritarianism, whether by corporate elites, cops, and the state security apparatus in this country or by repressive states in Russia, China, Hungary, Egypt, Saudi Arabia, India, Israel, Iran, Turkey, Syria, and elsewhere.

From a socialist perspective, a progressive third party is a stage in the socialist project, not an end in itself. It would constitute a new terrain on which revolutionary socialists, as a critical left wing, would strive to win over workers, students, intellectuals, and others.

Since the months leading up to the election, there has been a lull in the protest movements, and it is impossible to predict when they might revive—or when the strikes and workplace demonstrations that broke out during the pandemic might reappear. Continuing police violence will ensure a revival of BLM. But a new party will not arise naturally from movements; deliberate initiatives by activists can and must be taken so that an organized left political party is in place when the new wave emerges.

This is the project being explored by the Movement for a People’s Party. MPP began in 2016 as an effort to draft Sanders for an independent run for the presidency. Prominent supporters include Cornel West, former Ohio State Senator Nina Turner, Chris Hedges, Danny Glover, Oliver Stone, and former Minnesota Governor Jesse Ventura, and it’s been joined by a few branches of Our Revolution. The MPP held a virtual convention in August that was viewed on social media by 400,000 people. It plans to formally launch a political party in 2021, to run candidates in the 2022 midterms, and to put up a presidential candidate in 2024. It’s not clear how substantial the MPP is at this point, but it looks like a promising initiative that, at the very least, ought to attract collaboration from some elements in DSA. Some of its leading personalities endorse Democrats, which is inconsistent with the MPP’s guiding principle of political independence. If it gets off the ground and begins to develop an active membership, that inconsistency could be challenged internally on the basis of the MPP’s self-definition.

Biden has promised the ruling class that “nothing will change” for them. He will devote himself to protecting their wealth and power and to preserving the inhuman social system that they rule. Trumpism and the far right can only benefit from the status quo politics of Biden and the Democrats. Unless the left manages, and manages soon, to create a political alternative to these two deadly enemies, we are doomed. And step number one is for the left to break decisively with the Democratic Party and declare its political independence.

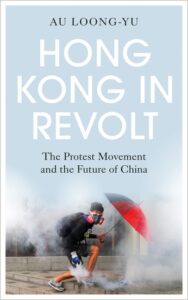

Review of Au Loong-Yu, Hong Kong in Revolt: the Protest Movement and the Future of China (Pluto Press, 2020)

Review of Au Loong-Yu, Hong Kong in Revolt: the Protest Movement and the Future of China (Pluto Press, 2020)

S

S

This article was written for L’Anticapitaliste, the weekly newspaper of the New Anticapitalist Party (NPA) of France.

This article was written for L’Anticapitaliste, the weekly newspaper of the New Anticapitalist Party (NPA) of France.

[Editors’ note: We are posting

[Editors’ note: We are posting

[Editors’ note: We are posting

[Editors’ note: We are posting

The Reed debate

The Reed debate

Last year a wave of militant protests spread across North Africa and West Asia, in a sustained, historic series of popular struggles. Emma Wilde Botta reviews A Region in Revolt: Mapping the Recent Uprisings in North Africa and West Asia edited by Jade Saab.

Last year a wave of militant protests spread across North Africa and West Asia, in a sustained, historic series of popular struggles. Emma Wilde Botta reviews A Region in Revolt: Mapping the Recent Uprisings in North Africa and West Asia edited by Jade Saab.

This article was written for L’Anticapitaliste, the weekly newspaper of the New Anticapitalist Party (NPA) of France.

This article was written for L’Anticapitaliste, the weekly newspaper of the New Anticapitalist Party (NPA) of France.

City Council just approved Chicago mayor Lori Lightfoot’s antiworker austerity budget, with 29 voting in favor and 21 voting against it. Lightfoot’s property tax increase passed with a slightly narrower margin of 28 for, 22 against. A large but strange assemblage spanning from the left-wing Alderwoman Jeanette Taylor to the notoriously corrupt boss Alderman Ed Burke found themselves voting against the mayor’s budget together. Opposition to the budget came primarily from those opposed to the hike in property taxes and from those opposed to another nail in the coffin of working Chicago.

City Council just approved Chicago mayor Lori Lightfoot’s antiworker austerity budget, with 29 voting in favor and 21 voting against it. Lightfoot’s property tax increase passed with a slightly narrower margin of 28 for, 22 against. A large but strange assemblage spanning from the left-wing Alderwoman Jeanette Taylor to the notoriously corrupt boss Alderman Ed Burke found themselves voting against the mayor’s budget together. Opposition to the budget came primarily from those opposed to the hike in property taxes and from those opposed to another nail in the coffin of working Chicago.

The movement to defeat Brazil’s right-wing authoritarian President Jair Bolsonaro made significant advances in the first round of local elections on Sunday, November 15, 2020. In São Paulo, by far the largest city in Brazil, the mayoral candidate of the Socialism and Liberty Party (“PSOL”) came in a strong second place, forcing a run-off election on Sunday, November 29, against the center-right incumbent Mayor Bruno Covas. The candidate supported by Bolsonaro was relegated to fourth place, widely seen as a significant popular rebuke.

The movement to defeat Brazil’s right-wing authoritarian President Jair Bolsonaro made significant advances in the first round of local elections on Sunday, November 15, 2020. In São Paulo, by far the largest city in Brazil, the mayoral candidate of the Socialism and Liberty Party (“PSOL”) came in a strong second place, forcing a run-off election on Sunday, November 29, against the center-right incumbent Mayor Bruno Covas. The candidate supported by Bolsonaro was relegated to fourth place, widely seen as a significant popular rebuke.

Review of Terrell Carver, Engels Before Marx (Palgrave Macmillan, 2020)

Review of Terrell Carver, Engels Before Marx (Palgrave Macmillan, 2020)

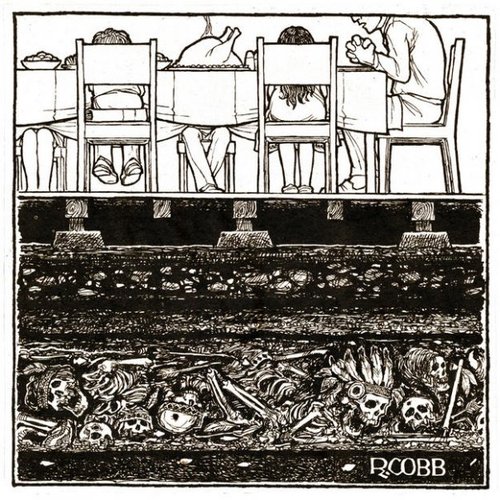

The mythic first Thanksgiving supposedly took place in 1620 when the Pilgrims who had emigrated from England to America gathered to thank God for a bountiful harvest, celebrating with the Indians who had helped them to survive their first year in Massachusetts. The real event, an encounter between the Indians and the English, was the prelude to the demographic catastrophe as disease killed most of the indigenous people and the start of the almost 300-year long conquest with the genocide of many tribes, the enslavement of others, the enormous land theft of an entire continent, and the establishment of the white, Protestant, and capitalist society that became the United States.

The mythic first Thanksgiving supposedly took place in 1620 when the Pilgrims who had emigrated from England to America gathered to thank God for a bountiful harvest, celebrating with the Indians who had helped them to survive their first year in Massachusetts. The real event, an encounter between the Indians and the English, was the prelude to the demographic catastrophe as disease killed most of the indigenous people and the start of the almost 300-year long conquest with the genocide of many tribes, the enslavement of others, the enormous land theft of an entire continent, and the establishment of the white, Protestant, and capitalist society that became the United States.

The nature of the American right was ill-understood during the Trump regime. The word “fascist” frequently circulated in liberal and left-wing circles. Yet, the only potential fascist was ousted from the White House before the Trump administration turned one. Now, the risk is forgetting that we still live under conditions favorable to right-wing extremism. The left needs to learn to operate in this Trumpism-prone world without, however, mischaracterizing it.

The nature of the American right was ill-understood during the Trump regime. The word “fascist” frequently circulated in liberal and left-wing circles. Yet, the only potential fascist was ousted from the White House before the Trump administration turned one. Now, the risk is forgetting that we still live under conditions favorable to right-wing extremism. The left needs to learn to operate in this Trumpism-prone world without, however, mischaracterizing it.

Book Review

Book Review The crucial turn in Trotsky in Tijuana from “historical” to “counter-historical” fiction comes in Chapter 8, where Mercador’s historical assassination of Trotsky’s is transformed into an attempted assassination and escape. I won’t reveal exactly how this happens; I’ll just say that the details are surprising in many ways and that Ralph plays a key role in Trotsky’s fictional survival. The last two paragraphs in this chapter dramatically foreground the shift into counter-historical discourse. All the verbs are conditional–“would have happened,” “would have been taken,” “would have run,” “would have made,” “would have meant,” “would have been left,” “would have evolved”—until the final sentence: “But remarkably, Trotsky survived” (p. 46).

The crucial turn in Trotsky in Tijuana from “historical” to “counter-historical” fiction comes in Chapter 8, where Mercador’s historical assassination of Trotsky’s is transformed into an attempted assassination and escape. I won’t reveal exactly how this happens; I’ll just say that the details are surprising in many ways and that Ralph plays a key role in Trotsky’s fictional survival. The last two paragraphs in this chapter dramatically foreground the shift into counter-historical discourse. All the verbs are conditional–“would have happened,” “would have been taken,” “would have run,” “would have made,” “would have meant,” “would have been left,” “would have evolved”—until the final sentence: “But remarkably, Trotsky survived” (p. 46).

This article was written for L’Anticapitaliste, the weekly newspaper of the New Anticapitalist Party (NPA) of France.

This article was written for L’Anticapitaliste, the weekly newspaper of the New Anticapitalist Party (NPA) of France.

Pro-Trump “Stop the Steal” protests in Pennsylvania.

Pro-Trump “Stop the Steal” protests in Pennsylvania.