The Reed debate

The Reed debate

Debates about the relationship between race and class, racism and capitalism, have been with us for as long as there’s been a socialist movement. In the past few years they have surfaced in and around the Democratic Socialists of America (DSA), particularly focused on the controversial writings of Adolph Reed. Reed was scheduled to give a talk sponsored by DSA’s Philadelphia and Lower Manhattan branches in late May, but he canceled his appearance after facing criticism from DSA’s Afrosocialists and Socialists of Color Caucus.

Reed is a distinguished African-American, left-wing political scientist, who has often had valuable things to say. But he’s always relished being a contrarian and I think that he, and a number of people influenced by him, have gone badly off the rails in their recent writing on race and class. They start from the same place that I start from, that we need a class analysis of racism, but from this they draw a series of mistaken conclusions.

First, they argue that if we have a class analysis, then we can explain racial inequality mainly in terms of class inequality and pay less attention to race. In an article in Catalyst last year, two of Reed’s co-thinkers argued that mass incarceration isn’t a product of racism. Reed published an article on Common Dreams in April arguing that racial inequality in health outcomes is due to underlying class inequalities and that to draw attention to the fact that “blacks have it worse” is to open the door to racist pseudo science.

Second, they conclude from this that socialists should focus on universal class demands—like Medicare for All—not on specifically anti-racist demands. Reed for instance, has been hostile to the Black Lives Matter movement and to the call for reparations. In fact, Reed argues that antiracism is counterproductive. He writes “because racism is not the principal source of inequality today, anti-racism functions more as a misdirection that justifies inequality than a strategy for eliminating it.” Elsewhere he claims that anti-racism gives cover to neoliberal identity politics, which elevates a few Blacks, women, gays, etc. to prominent positions, but which doesn’t challenge underlying inequalities.

Reed’s critics accuse him of class reductionism. He rejects the term, but I think it fits. He, in turn, accuses his critics of being race reductionists, who want to explain inequality in terms of race rather than class. There are no doubt some people who are race reductionists, but I don’t think that is the position of most of Reed’s left-wing critics. We critics agree that we need a class perspective, but we think that race and class are intertwined in much more complex ways than Reed allows.

History

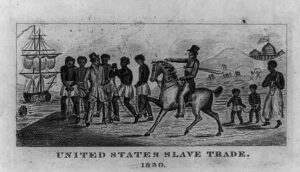

To explain what those ways are, we have to discuss the history of capitalism and its relationship to racism. My view is that capitalism created racism. That’s a controversial view—not everyone on the left, let alone in the mainstream, agrees—and I can’t give it a detailed defense in a short article, but I will point to one very important piece of evidence in its favor. The concept of race didn’t exist before the late 14th century. You won’t find it in ancient writings—in the Bible or Herodotus—it’s not even in Marco Polo’s diaries written in the 13th century. Its emergence coincides with the start of the modern African slave trade, and it was used to justify it.

As the Black historian Eric Williams argued in his classic study Capitalism and Slavery, racism doesn’t explain slavery, slavery explains racism. The slave trade was, of course, vital to the development of capitalism. In the 16th century, enslaved Africans were used to extract wealth from the New World that was essential to the primitive accumulation of capital in western Europe.

So, racism was absolutely central to the regime of labor relations that allowed capitalism to develop. But it also played a variety of other key roles. Almost immediately, ruling elites recognized its value as a divide-and-rule strategy.

In capitalism, like all class societies, a minority monopolizes most wealth and power. How can a small minority maintain its dominance over the vast majority? It will use open repression whenever necessary, but it’s hard to run a society just on repression, so ruling classes need to find ways to stop the majority from organizing together. Racism has played this role, especially in North America, since at least the 17th century.

Starting with Bacon’s Rebellion in Virginia in 1676, there were significant uprisings in the American colonies, with poor whites and enslaved Blacks often joining forces to fight against their masters. Ruling elites responded by passing slave codes to discipline Blacks, while giving small privileges to poor whites. According to the historian Theodore Allen, this amounted to “the invention of the white race.”

Allen conducted a detailed survey of 17th century records and concluded: “I have found no instance of the official use of the word ‘white’ as a token of social status before its appearance in a Virginia law passed in 1691.” Soon afterwards the Virginia Assembly proclaimed that all white men were superior to Blacks and passed a law requiring masters to provide white servants whose indenture time was up with money, supplies and land.

Such measures kept poor whites as well as Blacks subordinated to their masters. As Frederick Douglass later put it, “They divided both to conquer each.” This is why racism survived the end of slavery and persisted both as a method of justifying continued racial inequality—embedded in the labor market, housing, education, healthcare, and every other area of society—and as the most effective divide-and-conquer strategy available to the ruling class.

And racism also continued to play an important role in the justifications offered for colonial and imperial wars and conquest, which remain another central feature of capitalism.

This raises an interesting question—could capitalism exist without racism? I’ll answer that question in two ways. First, racism is thoroughly embedded and integrated in the capitalism we actually have. In order to end racism, we would have to dismantle the economic system that it is part of—not least because ending racism will require an enormous redistribution of wealth and power.

Second, at a more abstract level, we can ask whether in different historical circumstances, capitalism could have emerged without racism. I’m willing to entertain that possibility. However (and this is a big “however”), I don’t believe that capitalism could have emerged without some other, functionally equivalent, brutal system of oppression.

Capitalism is a system of economic exploitation, but it’s a system that can’t operate without methods of dividing the mass of the population using harsh systems of oppression. And, of course, in our society, race is not the only basis for oppression—we have sexism, homophobia, nationalism, ableism, and many other forms of oppression. Perhaps capitalism without racism is a theoretical possibility, but capitalism without oppression is not.

Practical conclusions

Finally, what practical conclusions should we draw?

Because capitalism and racism are intertwined, and because of the role that racism plays in dividing the working class, if we want to fight against capitalism and class inequality, anti-racism has to be at the center of our activity.

It’s not enough, as Reed and his supporters propose, to raise universal class demands. One of the things that makes it difficult to win such demands is racism. For example, one of the reasons why social benefits are so much worse in the United States than in other developed capitalist countries, is because racism is so strong here. The standard way of opposing government programs to provide welfare or healthcare, is to portray them as handouts to undeserving people of color. Even though most whites would benefit enormously from such programs, this trick has been enormously effective.

There is absolutely no reason to see anti-racist struggles as a diversion. They are vital if we want to build the kind of class unity necessary to take on the whole system. And it is worth adding that there is no sharp boundary between struggles for racial justice and fights for broader class demands. The experience and victories of the former, can—and often have—laid the basis for the latter. To mention just one example, many of the militants who led the upsurge in labor militancy at the end of the 1960s—including the successful postal workers’ national wildcat strike 50 years ago in 1970—were veterans of the civil rights movement and the black liberation struggle (and also the anti-war movement, the women’s movement, the gay liberation movement, and so on).

The fight against racism is not a diversion or an optional extra. It’s a key component of the fight for socialism.

This article is based on a talk given to the Madison-Area DSA in October.

The author would replace an alleged “class essentialism” with a “race essentialism,” conveniently forgetting, as Adolph Reed & others have pointed out, that the US black caste is itself riddled with class contradictions, and “racial solidarity” is often the calling card of black members of the professional-managerial class who seek political office. Yes, racism has divided white workers from black workers, but I don’t view this as much an eternal “racism” as I do the old leftist formulation, far more applicable and correct than today realized, of “false consciousness” and “ethnic/racial chauvinism.” I favor “Black and white, unite and fight!” over universal demands that not only would benefit all, but would disproportionately benefit working-class blacks; the paradigm model–Social Security. That’s what Bernie Sanders understands and articulates, and which, in his hands, becomes a uniting, rather than a dividing, force. I especially write this as an allegedly “privileged” blue-collar white male, who sees very little, if any, actual “privilege” in my own personal life–along with millions of other allegedly “privileged” white, especially white male, workers! It is certainly no “privilege” as in my case, being almost 74 and unable to afford to retire, lest I lose 3/4 of my income and fall into poverty. It is also no “privilege” to die, as many middle-aged white men are nowadays, of opioid addiction, alcoholism, or suicide! We within DSA (as I am, and which the author Phil Gasper is) talk much about “working class,” waving it around as a magic talisman, yet listen far too much to the voices of “woke” professional-managerial class members & such in training to enter the professional-managerial classes (i.e., university students) rather than “deplorable” blue-collar and ordinary white-collar workers, whom we pay lip service to, but do not talk TO, but only AT.

George, I’m not sure what article you are responding to, but not the one that I wrote. There isn’t one word in my article that could possibly be interpreted as “race essentialism” and I wrote about the importance of building class solidarity, not “race solidarity.” But you can’t build class solidarity by ignoring racism and calling for unity around universal demands. It is precisely because racism is so strong in the U.S. that these efforts have foundered. All socialists want to win universal demands like Medicare for All, but we also have to take on institutional racism, the violence of the police, and all other forms of racial inequality. These injustices won’t magically disappear by themselves. I have many criticisms of the CPUSA, but one thing they got right in the 1930s was seeing that the fight against racism was central to building a strong class movement. That’s why they championed justice for the Scottsboro Boys and took on racism in the unions. Confusing fighting racism with “race essentialism” just shows how far some U.S. leftists still have to go to relearn these lessons.

Are you just reiterating that old canard of “white privilege,” & that somehow, if you’re white, you’re automatically “privileged”? Because being white & working-class forced to work full-time at almost 74 doesn’t make me “privileged” in the least! Nor does making $15.25/hr. now when I used to live in poverty, could only find temp work for 14 yrs. Don’t ever forget–a lot of allegedly “privileged” white people suffer unconscionably too!

George, you have a talent for attacking straw men of your own invention. I think the problem is that you really don’t understand that there is more than one alternative to class reductionism. I tried to make that clear in my short article, but I also know how preconceptions often make it impossible for people to process what they are reading. The key quote is the one from Frederick Douglass: “They divided both to conquer each.” Because it divides us, racism results in all workers losing. That means that fighting racism is in the interest of white workers, and that if we want to build a united working-class movement, we have to prioritize that fight, not marginalize it. If we don’t do that, we can put forward all the universal demands we like and chant “Black and White Unite and Fight” until the cows come home, but racism will continue to divide workers and we won’t be successful. As I put it in the article, “anti-racist struggles … are vital if we want to build the kind of class unity necessary to take on the whole system.”

Thank you for being polite, and not calling me a “white supremacist,” as I was recently called on Facebook, along with other scurrilities. But you miss my point, and that is, white workers do not benefit from what you are saying they (at least indirectly) benefit from. They, too, are hurting, and it isn’t just African Americans, or other ethnic/racial minorities who are hurting. It’s all of us, and, yes, that does included a lot of supposedly “privileged” white folks such as myself, forced to work full-time at almost 74 because, unable to find decent employment even with a college degree until age 53, my Social Security is just too low. (By the Way, when I was almost 72, I wrote a poem on this, “I’m seventy-two, and must still work,” that was published right here in New Politics in January 2019. You can see it in my author’s archives here, where I’ve published in New Politics since 2011.) To bandy a bout terms like “class essentialism,” “white supremacy” and “white privilege,” to call far too much of the population “deplorables” and to ignore the Angus Deaton and Ann Case studies of premature death among supposedly “privileged” white males ages 45-55 of opioid addiction, alcoholism and suicide gives the lie to the notion that racial disparities and inequalities are largely or mostly a “black” thing that whites must feel guilty and masochistic about. Sorry, Phil, but we’re all in the same leaky capitalist boat, and pitting one race against the other when things are actually, now finally, ameliorating is counterproductive. I’m hardly “privileged” against, say, Clarence Thomas, Dr. Ben Carson, the late Herman Cain, Condoleezza Rice, or the far more Politically Correct Beyonce! I’m just a blue-collar retail Essential Worker in a grocery store who helps feed people during COVID-19 for $15.25/hour, and that’s hardly any notion of “privilege”! Too often, when the issue of “race” and “racism” is raised on the left, it’s raised in a way that ignores white working-class realities, as the new reply to you from Barry Finger points out.

George, in my previous response I wrote: “Because it divides us, racism results in all workers losing.” This is how racism works—it leaves white workers better off than their non-white counterparts, but both groups worse off than where they would be if they were not divided, with many whites accepting racist stereotypes about other groups. So let me repeat again, we need to fight against racism so that we can build a united class fight back against the whole system. I’m keeping this response brief because you are either not reading what I am writing or are just not able to understand it. So I think this conversation has run its course.

Far from a call for “race essentialism”, Phil’s piece is a call to address the actual conditions of the living breathing working class in this country. It is also the only way to break from the dialetic which Reed (and a number of other high profile professors) wish to reinforce, that the only alternative to their class reductive politics is some caricature out of the high academy in which they so lucratively toil. The idea that the 23 million people who took to the streets this past summer around an explicit anti-racist call somehow represent a “professional-managerial class” is an absurdity. You can’t build a class movement without speaking to people’s lived experience of class, which for a huge plurality of the living real-world working class includes the experience of oppression built explicitly upon their being interpellated as “Black” (or “brown” or “undocumented” or gendered, etc.). This is fundamental to Marxism. What Reed and others represent is a peculiar, and harmful, U.S. degeneration.

Excellent article And I do not, contrary to the above commenter (George Fish) see any racial essentialism in this article. People are racialized, and racial groupings are fluid, which is an anti-essentialist point. That is entirely consistent with the points made in the article about racism as a divide-and-conquer strategy and about antiracism being essential for any socialist movement.

The thing is, Adolph Reed agrees with Phil that racism, as we understand it, is the result of class exploitation. See:

http://www.kclabor.org/class_versus_race.htm

(The title is misleading — it’s not actually the title of Reed’s speech. And I don’t think there’s anything in the speech that Phil would disagree with.)

Reed: “My position is—and I can’t count the number of times I’ve said this bluntly,

yet to no avail, in response to those in blissful thrall of the comforting

Manicheanism—that of course racism persists, in all the disparate, often

unrelated kinds of social relations and “attitudes” that are characteristically

lumped together under that rubric, but from the standpoint of trying to figure

out how to combat even what most of us would agree is racial inequality and

injustice, that acknowledgement and $2.25 will get me a ride on the subway. It

doesn’t lend itself to any particular action except more taxonomic argument

about what counts as racism.”

Source: https://static1.squarespace.com/static/5d07e9421ad6370001589688/t/5d785fe55bd75417004afeec/1568169958124/Limits+of+AntiRacism.pdf

I imagine everything that Reed says above about the Obama administration is also something Phil would echo. And Reed has made clear, repeatedly, that “Marxism’s most important contribution to making sense of race and racism in the United States may be demystification. A historical materialist perspective should stress that “race”—which includes “racism,” as one is unthinkable without the other—is a historically specific ideology that emerged, took shape, and has evolved as a constitutive element within a definite set of social relations anchored to a particular system of production.”

Source: http://libcom.org/files/Marx,%20Race%20and%20Neoliberalism%20-%20Adolph%20Reed.pdf

I.e., capitalism is necessarily “racial capitalism” so there’s no need for a specific term like “racial capitalism.” There is no other capitalism.

As for the Catalyst essay — either the research is correct or it isn’t. I’ve talked with Adaner Usmani. I think his critics in Spectre and elsewhere have caricatured him. His political point is that socialists have to oppose the carceral state even if racism isn’t the *key* factor in its development — and that *even if it’s true* that working-class Black communities are more prone to street violence than other areas, this doesn’t justify police brutality or locking up millions of people.

Reed’s son Toure, in the context of an essay about his personal experience with racism, further argues that “It’s not unreasonable to attribute neoliberalism’s disproportionate impact on blacks, in part, to the historic legacy of racism. But it is important to situate African Americans’ historic and contemporary experiences within the broader currents of American political economy…So those of us who insist that the elimination of racial disparities requires social-democratic policies — a right to a job at a living wage, taxpayer-funded (free) higher education, and national health care — are not denying the existence of racism, even if race is only about as real as the Easter Bunny…

We do insist, however, that narrow demands for policies intended to redress disparities, at the expense of policies centered on downward redistribution of wealth, are the equivalent of demands for berths on a higher deck on a sinking ship.”

There’s no political distance between Adolph and Toure. You can ask Adolph yourself. I have his email address.

Isn’t it clear that the Reeds’ main target — bracketing the idea of the professional-managerial class itself — is the mainstream of the Democratic Party and its defenders in the New York Times, MSNBC, CNN, etc.? Don’t we good socialism-from-below types oppose all these people just as Reed does? So what exactly is the beef here? Because I don’t see the Reeds saying “don’t talk about race.” They’re saying “don’t get pulled into talking about race like liberals talk about race.” It’s an important difference.

“Race” and “class” are not equivalent concepts. Race is a social construct, as we know. Biologically, it has no meaning. Historically, race was conjured forth by racism. And racism continues to generate racial “distinctions” and new “bothered” groups. Class, in Marx’s terms, is *itself* a social relation – a power relation – as well as a structural constituent element of our society. The equivalent term describing a power relationship involving BIPoC and their oppressors is racism. We rarely use “classism” – liberals sometimes do – because it abstracts from the exploitative relationship in which workers are imbedded and turns class into a simple question of status. Similarly, “elitism” doesn’t fit the bill. When we use the shorthand “race and class” we are attributing to race a material reality that it doesn’t have. I would suggest, cumbersome as it may seem, that we use the expression “class and racism.”

Phil Gasper writes,

“Capitalism is a system of economic exploitation, but it’s a system that can’t operate without methods of dividing the mass of the population using harsh systems of oppression. And, of course, in our society, race is not the only basis for oppression—we have sexism, homophobia, nationalism, ableism, and many other forms of oppression. Perhaps capitalism without racism is a theoretical possibility, but capitalism without oppression is not.”

Phil is open to the suggestion that capitalism without racism is a plausible theoretical conceit, but insofar as American (and European) capitalism was intimately linked to African slavery, racism arose as a self-justifying bridging ideology. Otherwise the tension between the Enlightenment assertion of human equality, which the bourgeois revolutions so proudly championed against feudalism, and the racial subordination of one section of humanity which capitalism practiced, could not otherwise be rationalized. Notions of racial superiority were materially rooted in an “actually existing” but historically transient capitalist hybrid with chattel slavery. Fair enough.

But the question then arises, why does this anachronistic ideology survive, and even at times such as these, seemingly flourish? Obviously the institutions of slavery no longer nourish racism. What then is its wavelike revival rooted in? According to Phil, if I understand his argument properly, it is foisted on society, or periodically resuscitated, from the top as a sort of divide-and-conquer strategy by capitalists to keep the masses from coalescing around a united program of opposition.

Yet, I find this unconvincing on two grounds. First, capitalism has methods embedded in the very warp and woof of exploitation that very effectively inculcate the habits of submission: the struggle between the employed and the unemployed for jobs, between the skilled and the unskilled for pay; the ongoing process of deskilling which disempowers; automation; speedups; outsourcing; gig work … In a phrase, capitalists purchase working class capitulation through their perpetuation of sweeping economic and social insecurities, an exhausting and exhaustingly frustrating hamster wheel, that keeps capitalist abundance just beyond reach.

What need, therefore, do bosses have for these other forms of oppression that pit worker against worker and that portend a potential disruption of workflow? And if they do need them, it seems somewhat odd that corporations invest so much time and effort into HR departments to pacify work floors through affirmative action, diversity training, and other forms of policing the environment against racial (and sexist, etc) intimidation. For the same reason that capitalists oppose the disorderliness of unions, they also abhor a workplace environment where toxic internecine divisions threaten the collaborative ability of employees to maximize the bottom line.

Instilling the habits of obedience therefore also necessitates forcing diverse working class populations to suppress their prejudices and animosities during the work day and recruits an activist management to the task of isolating and weeding out those who cannot so discipline themselves.

Why, then, does the suppression of racism in the heavily policed workplace erupt so wantonly in political spaces?

This brings up my second objection. It is not capitalists that promote racism (except for the most troglodyte of hangovers, most pride themselves and not totally hypocritically for their “enlightened” and “liberal” social leanings, virtues that cost them nothing), but the capitalist system itself. The system, based on perpetuating scarcity in the midst of unparalleled abundance, cannot help but do so. Far from being a ruling class initiative, white chauvinism arises from below as an immanent, instinctive group strategy to leverage favored access to jobs, security and scarce public goods through exclusion. This is the unfortunate truth that socialists are often loath to face and which cannot be reconciled in the context of Phil’s approach.

This has manifold implications, part of which is relevant to the debate over Reed’s contributions. The first is that racism cannot be simply reduced, as it often is, to prejudice wedded to power without qualifying what “power” means. The power of white workers resides in their numbers and their social weight in the economy, but not in their wealth and alleged privilege. Racism is a survival strategy, a social-Darwinistic identity politics, of the disunited jockeying for position in the context of class fragmentation. It is a reactionary alternative that arises in the absence of militant class struggle politics. Those with actual wealth and privilege have no direct material stake in racism. They can afford the woke pretense of floating above the fray and giddily indulge themselves with guilt-tripping taunts against their morally inferior white lessers.

But this also suggests where an overreliance on an alternative, progressive, “identity politics” of the excluded and marginalized can open reactionary possibilities. It is, of course, the god-given right of those who are attacked for their identity to defend their rights and dignity based on that self-same identity. It is not only their right, it is their duty.

But when those who are the objects of racism seek to rebalance their power disadvantage from below in alliance with the woke sections of the ruling class (eg Ford Foundation and myriad others), the jockeying see-saw of the exploited and oppressed is perpetuated. From the perspective of the excluded, any advance that this top-down alliance effectuates is undoubtedly a social advance.

But it is a lesser-evil setback for socialism, and of working class unity. It keeps the underlying dynamics that give rise to racist working divisions alive.

I think this is the larger significance and heart of Reed’s contribution.

I like your response, Barry, and what I especially like is the way it points out the direct working-class economic concerns that face ordinary blue-collar & white-collar workers, which are not necessarily those of higher-lever professional-managerial class employees (in a corporate-dominated world, almost everyone, of course, is an employee–even CEOs!)–as you point out, “diversity” and “social liberalism” (which are, of course, quite different from amelioration of actual real-life problems facing most black, Latino, Asian, women & gay employees or unemployed!) cost them nothing! DSA, e.g., talks much about the “working class,” but only as a content-empty cipher, because “working class” means–adherence to “working class” DSA values, programs & policies! (Yes, it really is that logically circular, as you well know.) That’s what Adolph Reed noted in all these calls by “professional-managerial class” black politicians in their appeals to “racial solidarity.” You hit the proverbial nail right on the head, Congratulations!

The particular historical shift is the adaptation of the black empowerment movement, which broke a real barrier to democratic rights for black folks, following on the (tentative) fulfillment of the 15th Amendment, to neoliberalism – graft and patronage for the few at the expense of the many. This raises questions about the value of black unity, which became a default mode (partially) as a means to defend political gains by black officeholders under permanent attack by white nationalists. To get there required a giant step away from mystical notions of racial identity that pervade the left from center to hardcore. Whether or not Reed has conducted himself in a way that most effectively stimulates thinking on this question, the question will not go away.