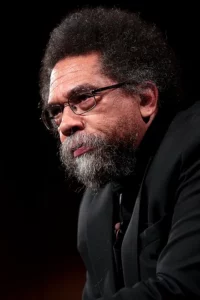

Cornel West, candidate for president.

Cornel West announced in early June that he was running for president of the United States as the candidate for the People’s Party and then as aspiring to be candidate of the Green Party. Now he’s running as an independent.

This series of articles explores the experience of Black political candidates for the nation’s highest offices.. In Part 1 of this article, we looked at the reaction of the left to West’s candidacy. In Part 2 we turn to look at the experience of four Black presidential candidates in 1968. In Part 3 we examined the campaign of Shirley Chisholm in 1972. In Part 4 of the series we recalled the experience of Angela Davis, twice candidate for vice-president. In Part 5 we looked at the experience of Clifton Berry in 1964. In this article we look at Rev. Jesse Jackson’s two campaigns in 1984 and 1988.

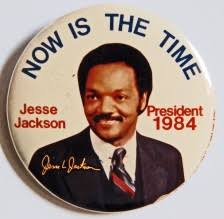

Jesse Jackson for President 1984 and 1988

Jesse Jackson for President 1984 and 1988

Rev. Jesse Jackson was the most significant Black leftist political candidate of the twentieth century, running for president in 1984 and 1988, coming in third and second in the Democratic primaries in his first and second campaigns respectively. Though in places his campaign took on the character of a movement, nevertheless he not only failed to win election, but also failed to convince Democratic Party to adopt his progressive program. While many Black voters and others admired and took pride in his achievement, some on the left felt he had ultimately served the Democratic Party establishment.

Jesse Jackson was born in Greenville, South Carolina to 16-year-old Helen Burns; his father was her neighbor, Noah Louis Robinson. Jackson was tormented by the stigma of his illegitimate birth. “When I was in my mother’s belly, no father to give me a last name, they called me a bastard and rejected me.” (Marshall Frady, Jesse: The Life and Pilgrimage of Jesse Jackson New York: Random House, 1996), p. 78.) Reading his biography, one has the sense that this initial stigmatization and rejections remained at this center of his psyche and that in reaction to that sense of rejection it provided him with his driving ambition.

A year later, his mother married Charles Henry Jackson, a maintenance worker who adopted Jesse and gave the boy his last name though over the years he largely neglected him. Jesse Jackson grew up in a poor black community, protected as he said by “the triangle,” of which the first corner his mother and grandmother, the second his school teachers, and the third the church. (Fraday, Jesse, p. 101.) Mother, preacher, and teacher all demanded that the young Jesse prove himself, that, as he might have said later, he “be somebody.” As one biographer writes, “In fact, the strenuous discipline in which he was raised left him forever after obsessed with the traditional rectitudes of grit, puck, industry, pertinacity—these staunch verities that, as he saw it, provide his deliverance from the claim of the futility of and the abjectness of the communing enclosing him.” Those tenets and what he himself calls his “conservative Christian orientation” provided Jackson his moral compass. (Frady, Jesse, p. 106.)

Even as a youth others recognized his perceptiveness, his “flair of phrase” and his “ambitiousness.” Others told him that he was special. When he was a teenager he told his biological father that he had had a dream. “I dreamed I was a preacher, leading the people through the rivers of the waters.” As a leader of the church youth group he frequently spoke in church. “Church was my laboratory where I could develop and practice my speaking powers with more and more confidence.” When he was 15, he told a friend, “I want to be a minister.” (Fraday, Jesse, pp. 111-16.)

Jackson attended Sterling High School, segregated like all southern schools at the time, where he was elected class president, earned letters in football, basketball, and baseball, and in 1959 finished tenth in his class. As a high school student, following the victory of the Montgomery, Alabama bus boycott led by Rev. Martin Luther King, Jr, Jackson made the daring and risky move of sitting in the front of the bus in Greenville. Home from college, in 1960 he and half a dozen other students engaged in a small sit-in protest to desegregate the Greenville public library, his first civil rights activism, but when his step-father objected to his getting arrested, he left the growing movement.

Like many Blacks, Jackson hoped to escape the South’s stifling racism by going north. A talented quarterback in high school, he turned down the offer of a minor league football contract and accepted a football scholarship to the University of Illinois at Urbana in 1959, proud to be at a Big Ten school. There, however, he had no chance of becoming a quarterback, a position reserved for white athletes. And he was warned “not to socialize” with the white coeds. Though he had left the South, he had not escaped America’s pervasive racism. On campus he was part of “an isolated minority” and fell into depression. He later said his experience at the U of I “came close to breaking my spirit.” (Fraday, Jesse, pp. 138-40.)

Into the Civil Rights Movement

So, after several unhappy months at the U of I, Jackson left. He now enrolled at the North Carolina Agricultural and Technical College, a mostly black school in Greensboro. It was there that he met Jacqueline Lavinia Brown, courted her, and when she became pregnant married her. He and his wife began their family and he focused on his studies, and though the civil rights movement was burgeoning all around him, he kept his distance. Still he found time to attend the March on Washington in March, 1963.

Then one day that same year, urged by mentors and friends to join the movement, he gave his first speech to a rally of about 100 students preparing to take action. Jackson rose and spoke: “History is upon us. This generation’s judgment is upon us. Demonstrations without limitation! Jail without bail! Let’s go forward!” And the group moved out. At that moment Jackson found his voice, demonstrated his charisma, and took up his calling. (Fraday, Jesse, p. 173.) He organized more protests and a warrant was issued for his arrest and he was jailed, taking advantage of the situation to write a “Letter from a Greensboro Jail” in imitation of Martin Luther King’s famous missive. Thousands of people marched through Greensboro demanding his release, giving proof that the movement would support him and lift him up and as a result, he went free.

After graduating with a degree in sociology from North Carolina A & T, Jackson received a scholarship to attend Chicago Theological Seminary and moved his family to the Windy City. He got a job organizing for the Coordinating Council of Community Organizations (CCCC), a local civil rights group. In 1965 he joined the march from Selma to Montgomery, Alabama and his drive and organizational ability caught the attention of King and other SCLC leaders. He asked to speak to King and urged him to take his movement north to Chicago. A month later King brought Jackson on to the SCLC staff, at 24 years of age the youngest of King’s aides. Jackson was put in charge of SCLC’s economic campaign called Operation Breadbasket, organizing mass boycotts of white companies to pressure them to hire Black workers and buy from Black-owned businesses.

Jackson came on board just as King was preparing to transform his civil rights campaign in the South into a national movement. So he succeeded in getting King to come to Chicago where King led a march into the suburb of Cicero and was met by hate filled demonstrators who left him shaken. A “Summit” with Mayor Daley produced a document full of hollow promises. “Most Black Chicagoans regard it as a sell-out.” The SCLC leadership was aware that they had failed to meet their goals. (David Levering Lewis, King: A Biography, Urbana: University of Illinois, 1970, p. 351.)

Just three courses short of earning his master’s degree, he left to throw himself into the civil rights movement. He soon began working with Rev. Martin Luther King, Jr. participated in the famous civil rights marches in Selma, Alabama, and worked in the Southern Christian Leadership Conference that King had founded. In 1966, King made Jackson head of the Chicago branch of Operation Breadbasket, an organization led by Black ministers and businessmen to economically improve Black people’s lives . In that capacity, Jackson organized a “selective patronage” campaign to reward stores that hired Black people and boycot those that didn’t. When Operation Breadbasket became a national organization in 1967, King made Jackson the national director. Under Jackson’s leadership, some 40 companies were pressured to hire several thousand Black workers.

However, Jackson’s political style and personal ambition brought him into conflict with Rev. Ralph Abernathy, who had become head of SCLC after King’s 1968 assassination. Jackson then created his own organization, Operation PUSH: People United to Save Humanity. Jackson’s break from SCLC and establishment of PUSH coincided with the migration of the civil rights struggle from the South, where it had fought de jure (legal) segregation, to the North, where Black people confronted systemic de facto segregation in all areas of life. Northern society and urban politics differed fundamentally from the South and required different political analyses, strategies, and rhetoric.

King’s anti-Vietnam War position and his failure in Chicago left him more criticized and more isolated, nevertheless he turned toward the organization of the Poor People’s Campaign, seeking alliances with other minority groups like Mexicans, Puerto Ricans, Native Americans and Asian Americans in order to change the country’s economic agenda. The goal was to bring economic justice to working class and poor Americans by improving their employment and housing.

In March of 1968, a strike by 1,300 black garbage workers in Memphis, Tennessee came to King’s attention and he decided to go there and stand in solidarity with them. The Memphis workers’ strike was a way both to continue the civil rights movement in the Southin which he had been involved for almost 15 years and to take up the issue of economic inequality which was his new cause. The strikers won signs reading, “I am a man,” conveying their demand for fair treatment, respect, and equality. King spoke inspiring words to the strikers expressing his confidence in the justice of their fight. Jackson, part of King’s inner circle, went back to the motel with him, and there on the balcony on April 4, 1968 King was assassinated.

Operation PUSH

Back in Chicago immediately after King’s murder, Jesse was a guest on the Today Show, where he was asked about the assassination. The highly emotional Jackson said, “I come with a heavy heart because on my chest is the stain of blood from Dr. King’s head…He went through literally, a crucifixion. I was there. And I will be there at the resurrection.” Jackson’s presence at King’s assassination allowed him to claim legacy. King was dead, Jackson would continue his work.

Jackson would work from his base in Operation PUSH, which he now called a “Rainbow Coalition,” a term meaning unification of Blacks with Latinos, Native Americans, Asians, and progressive whites. Jackson appropriated and gave different content to that term coined by Fred Hampton, leader of the Black Panthers in Chicago, who had been assassinated by police in 1969; while the Panthers had preached revolution, Jackson advocated Black capitalism and political reform.

To finance PUSH, Jackson raised money from a variety of Black politicians, business people, and artists, among them Manhattan Borough President Percy Sutton; Gary, Indiana Mayor Richard Hatcher; singer Aretha Franklin; football star Jim Brown; and actor Ossie Davis. Black community leader, physician, and businessman T.R.M. Howard, a major figure in the fight for civil rights in the South, served on the PUSH board and headed its finance committee. PUSH ran a variety of educational programs, pressured Anheuser Busch (Budweiser, etc.) and Coca Cola to institute affirmative action, and produced radio broadcasts about Black issues. PUSH also established ties with such important Democratic Party leaders as President Jimmy Carter, to Secretary of Health, Education, and Welfare Joseph Califano, and Secretary of Labor Ray Marshall.

Operation Breadbasket and Operation PUSH gave Jackson a strong base in Chicago’s enormous black population, which reached a peak of 1,187,905 in 1980. And PUSH’s national campaigns gave it a reputation of fighting for justice among 26.5 million Black people, who then made up 11.7 percent of the total U.S. population. Jackson had networks of Black supporters among political, business, sports, and arts elites. And in a community in which Protestant ministers had historically played the role of spokesmen, he was himself a Black Baptist preacher. Driven by ambition and well aware of these assets, Jackson decided to run for president in 1984. Linked as he was to Chicago’s Black bourgeoisie and to the Democratic Party, it would be hard to deny that he was a capitalist candidate for president. Yet he was also a populist with a large Black proletarian following. A master politician, he was able to juggle the two roles. While he was based in Chicago, he was the most prominent spokesperson for Black people at the twentieth century.

Jackson’s social and political platform as a Black leader was in the tradition of FDR’s New Deal and LBJ’s Great Society, combining calls for economic programs for the working class and the poor with demands for civil rights. But nothing in it challenged the fundamentals of capitalistism itself. Jackson was an ardent advocate of social reform, but certainly no revolutionary. In any case, continuing his work through the next decade and a half, he decided to enter electoral politics.

Jackson for President

Jackson’s decision to run for president in 1984 was an expression of what Bill Fletcher, Jr. has called a “Black political insurgency in the late 1970s, early 1980s” that included the 1983 mayoral campaigns of of Mel King in Boston in andof Harold Washington in Chicago. , both of which found supporters among progressives on the far left, particularly among tthe Maoists.

Jackson’s 1984 campaign had many of the characteristics of both a social movement and a protest campaign. His activist campaign linked his presidential bid to the struggles of Blacks and Latinos, poor communities, labor unions, and workers. In sharp contrast to other r earlier Black presidential candidate s, his vote totals were impressive: 3,282,431, or 18.2 percent of the primary votes. He won five primaries and caucuses: Louisiana, the District of Columbia, South Carolina, Virginia, and one of two separate contests in Mississippi making him the first African-American candidate to win any major-party state primary or caucus.

Writing at the time, Prof. Cornel West, who is running for president in the 2024 race, praised Jackson’s campaign, but criticized both the white and Black left . Of the Black movement, West wrote,

First, Jackson’s charismatic style of leadership accentuates spontaneous and enthusiastic attraction at the expense of constructing enduring infrastructures. Second, Jackson’s most loyal constituency—the black community and especially the black churches–presently seems to lack the patience, resources and ideological wherewithal to engage in prolonged political organization. And lastly, black—and to certain extent Jackson’s—allegiance to the Democratic Party diffuses energies which could be direct toward alternative political mobilization.[i]

Unfortunately, this critique was – and remained – accurate.

Of the white left, West said, “the American left continues to hold black radicalism at arm’s length.”[ii] But this was not completely true. Though not many, some white liberals and progressives rallied to Jackson’s 1984 campaign , and more did so in 1988. For example, Bernie Sanders, Mayor of Burlington, Vermont, backed Jackson, saying he believed that he could win white working class votes. Of left organizations the Communist Party, in a demonstration of political triplicity, worked in the 1988 Jackson and Mondale campaign, even while running its own Hall-Davis campaign. Most involved were the Maoists who had become the dominant trned of the far left of the 1970s (as even their opponents recognized), but who were discarding revolutionary politics for electoral populism.

The Maoist movement had gone into crisis not long before Jackson’s campaign. A group of talented organizers in the Revolutionary Communist Party left in 1977 to found the Revolutionary Workers Headquarters, while the Comment Party Marxist-Leninist (previously the October League) dissolved in 1980. The League of Revolutionary Struggles (LRS), founded in 1978, similarly dissolved in 1990. The Maoists, those still in organized groups and those now without a party, threw themselves into both Jackson campaigns, particularly in 1988.

Bill Fletcher, who came out of that milieu, viewed the 1988 campaign very favorably: “The campaign sought out the sectors of society that were ignored, that were marginalized, reaching out to white famers in the Midwest…reaching out to the workers that were on strike, that were being crushed, speaking to them.” He argues that the 1988 Jackson campaign:

…brought together a very broad segment of left and progressive forces, many of whom had not been able to work on anything for years, but suddenly realized that they shared something in common. That was what was unique. People on the left made a decision that this campaign was strategically critical; [and they] got into the campaign, dug in deep, and started building, building labor constituencies, building farmers [groups]….This was the work of people on the left and I think it was exceptional.

Jackson found support not only from Blacks, but also from Puerto Ricans, Mexican Americans, and Native Americans. He crisscrossed the country, speaking in Black, Latino, and white working-class communities. He showed up at union picket lines and marched with immigrants. He seemed to be everywhere demanding change.

Jackson did exceptionally well in 1988 more than doubling his votes in the 1984 campaign. He received 6.9 million votes and won 11 contests: seven primaries (Alabama, the District of Columbia, Georgia, Louisiana, Mississippi, Puerto Rico and Virginia) and four caucuses (Delaware, Michigan, South Carolina, and Vermont): he won 29.7 percent of the vote compared to the 70 percent for Governor Michael Dukakis of Massachusetts.

The Afteermath

The leftists who had supported him believed that his campaign had laid the basis for an ongoing movement. And perhaps it might have, but Jackson wasn’t interested. As Fletcher says,

After the November election there was a great debate that took place in Rainbow circles and the question was: What happens to the Rainbow?. There were many promises about how the organization would be built. We were told that it would be a mass, democratic organization that we would be building around the country, that would basically take the approach of working inside and outside the Democratic Party. That was thrilling.

There was an element within Jackson’s constituency that started to make the argument that the Rainbow’s future was to be determined by Jackson. Not to be determined by the thousands of people who had dedicated themselves to his campaign. When you’re dealing with a charismatic figure, it is very hard to rein them in.

Jackson misanalysed that moment at that juncture and thought that a permanent Jackson wing of the Democratic Party had emerged as a result of the 1988 campaign. And it hadn’t. In March of 1989 there was a meeting of the executive board of the Rainbow. To the surprise of many people, myself included, Jackson came forward with a plan to reorganize the Rainbow into what was a personal or a personalist organization.

I don’t think that we recovered. Things didn’t play out as we hoped, but it was pathbreaking, in terms of the issues that were brought to the surface, not like anything that had arisen perhaps since the 1940s. Despite any weaknesses on Jackson’s part as an individual, he has to be credited with understanding the moment up until late 88, and that’s when the songs of the sirens misdirected him.

Jackson persisted. The Rainbow disappeared.

With his base in Operation PUSH in Chicago and his relationships with Black business people, corporations, and the Democratic Party, Jackson remains a prominent Black political figure. He has never deviated from his commitment to social reform—but within the limits of the Democratic Party and Black capitalism. He is reputed to have a personal wealth of $9 million. In 1996 he established the Wall Street Fund to support “minority vendors,” that is Black business, though in 1999 praised Donald J. Trump. He remains today both a major African American leader and a contradictory figure.

Conclusion

As we have seen, when Black candidates have run on third-party presidential or vice-presidential tickets—whether Communist, Socialist, or Peace & Freedom—they received few votes and seldom contributed to building the social movement or changing American society. But when they ran in the Democratic Party, as Chisholm and Jackson did, they could receive significant numbers of votes, and in the latter’s case, even create around the electoral campaign the feel of a movement, but because hey remained tied to the Democratic Party,, it absorbed the candidates and their supporters but gave little in return.

Throughout the 1990s and 2000s there were many Black candidates for president running on the ballot lines of small leftist parties or as independents, but tnone were significant figures, heir social impact was insignificant and they received only a small number of votes. They hardly warrant our attention. So we turn in the next section to look at the Black presidential candidate, who also ran as a candidate of the left and won, and then governed as a neoliberal: Barack Obama.

Thanks to Michael Letwin for his comment on an earlier version of this article.

Notes:

[i] Cornel West “Reconstructing the American Left: The Challenge of Jesse Jackson,” Social Text , Winter, 1984-1985, No. 11 (Winter, 1984-1985), pp. 3-19

[ii] Ibid.

Many grammatical errors in this piece which make me think it could’ve used another editor. There’s also an important error of fact: Dukakis did not win 70% of the vote in the 1988 primaries, he got around 42%.