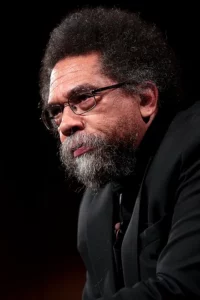

Cornel West announced in early June that he was running for president of the United States as the candidate for the People’s Party and then as aspiring to be candidate of the Green Party. This series of articles explores the experience of Black political candidates for the nation’s highest offices.. In Part 1 of this article, we looked at the reaction of the left to West’s candidacy. In Part 2 we turn to look at the experience of four Black presidential candidates in 1968. In Part 3 we examined the campaign of Shirley Chisholm in 1972. In this fourth part of the series we look at the experience of Angela Davis, twice candidate for vice-president.

Cornel West announced in early June that he was running for president of the United States as the candidate for the People’s Party and then as aspiring to be candidate of the Green Party. This series of articles explores the experience of Black political candidates for the nation’s highest offices.. In Part 1 of this article, we looked at the reaction of the left to West’s candidacy. In Part 2 we turn to look at the experience of four Black presidential candidates in 1968. In Part 3 we examined the campaign of Shirley Chisholm in 1972. In this fourth part of the series we look at the experience of Angela Davis, twice candidate for vice-president.

In the 1980s, voters had an opportunity to support Black candidates for the nation’s highest offices in two different parties. Angela Davis, for vice-president on the Communist Party ticket in 1980 and 1984, and Rev. Jesse Jackson for president in the Democratic primaries in 1984 and 1988. We look here at Davis’ campaigns.

In the 1980s, voters had an opportunity to support Black candidates for the nation’s highest offices in two different parties. Angela Davis, for vice-president on the Communist Party ticket in 1980 and 1984, and Rev. Jesse Jackson for president in the Democratic primaries in 1984 and 1988. We look here at Davis’ campaigns.

Davis was born in Birmingham, Alabama in 1944 to a working-class family with connections to the Communist Party. Her paternal grandfather had been a member of the Communist Party. (Angela Davis, An Autobiography, New York: Bantam Books, 1974, p. 84.) Her father was a gas station owner and her mother was an elementary school teacher. Her parents were involved in civil rights organizations and also in the orbit of the Communist Party, as were family and friends. She grew up in this Black Communist milieu.

An outstanding student, virtually her entire education came through scholarships. As a teenager she moved to New York and lived with a white family of party fellow travelers while she attended Elisabeth Irwin High School, a private progressive high school some of whose teachers were Communists who had been blacklisted and couldn’t teach in the public schools. In her high school she became interested in the utopian socialists and their communities and read The Communist Manifesto, which, she wrote, “hit me like a bolt of lightning.” (Davis, Autobiography, p. 109). At about the same time, at around the age of sixteen, she was invited to join Advance, the Communist Party Youth Group filled with the children of national leaders of the Communist Party. Many of Advance’s meetings were held in the home of Communist historian of African American slave rebellions Herbert Aptheker whose daughter Bettina was a leader of Advance. (Davis, Autobiography, p. 111.) Through her mentor Herbert Aptheker she was inculcated in the most Stalinist version of Communist politics.

Thanks to her Communist Party connections, she attended the Eighth World Festival for Youth and Students held in Helsinki, Finland in 1962. It had been organized by The World Federation of Youth and Students, a Soviet dominated organization. There she had an opportunity to meet Communist youth from other countries. Throughout her youth and young adulthood, the Communist Party guided and assisted Davis as she moved from country to country in Europe and from city to city in the United States. Though she did not join the CP until later. The party did not have to direct her, because she had grown up in it and shared its positions and outlook, though her involvement in the militant and armed Black movement represented her own decision.

She enrolled at Brandeis University in 1961 where she studied modern French literature and became interested in the existentialists like Jean Paul Sartre and Albert Camus. While there she was impressed to hear a talk by Malcolm X, then still a leader of the Black Muslims. She took advantage of an undergraduate program to study in France spending time in classes in Biarritz and Paris. While there she learned of the racist bombing of the Sixteenth Street Baptist Church in Birmingham on September 15, 12 where four girls ages 11 to 14 had been killed, all from families that were friends of her family.

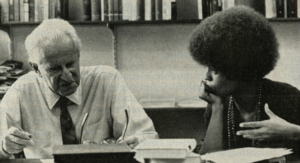

When she returned to Brandies, she began to attend the lectures of the German Marxist philosopher Herbert Marcuse. He was not a Communist but rather a member of the Frankfurt School for Social Research. He began to meet regularly with him to discuss the history of philosophy. Those discussions led her to decide to pursue a career in philosophy, going off to Frankfurt to study with Theodor Adorno, also of the Frankfurt School.

In West Germany she participated in the radical social movement of the era led by SDS (Sozialistische Deutsche Studentenbund or German Socialist League of Students). She also visited East Berlin, part of Communist East Germany, a thorough-going police state, for which she expressed naive admiration. But she was feeling out of touch with the growing and ever more militant Black wanted to get back to the United States. She persuaded Herbert Marcuse to take over the supervision of her PhD at the University of California at San Diego from which she received her doctorate.

Herbert Marcuse and Angela Davis at work on philosophy together.

Davis found the San Diego Black movement to be a backwater, so she began to become involved in the more sophisticated and militant Black milieu in Los Angeles. In 1968 she was invited to a meeting of the Che-Lumumba Club, the Black collective within the Communist Party and was impressed by a talk by Charlene Mitchell, the club’s leader. Still Davis declined to join the CP at that time. She did, however, join the Black Panther Party and soon became involved in its fights with a rival faction, buying and carrying a gun to defend herself. She also joined and became active in the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), which was trying to expand its West Coast presence. Through her role in these groups and the campaigns to free jailed leaders Huey Newton of the Panthers and Rap Brown, head of SNCC, she met many national leaders of the black movement.

When the Los Angeles movement went into crisis and the local SNCC chapter collapsed, Davis decided to more seriously consider joining the CP. She began to meet and talk with veteran CP leader Dorothy Healey and she read Lenin’s What Is To Be Done? and W.E.B. DuBois’s essay on his decision to join the Communist Party. In July 1968 she joined the Che Lumumba Club and the Communist Party. (Davis, Autobiography, pp. 185-88.) When her CP membership became an issue within the Panthers, at about the same time as the murder of three L.A. Black Panthers, Davis returned to UCSD in La Jolla and began to work there with the Black Student Council. Their demand was that UCSD’s third college campus be called the Lumumba-Zapata Campus and the Council organized protests, won the support of Marcuse and some other professors, and organized a brief take-over of the registration building.[1]

That summer of 1969, Davis went to Mexico City and then to Havana, Cuba to work for a while in the cane fields as Fidel Castro pressed Cubans to harvest ten million tons of sugar. Davis, like many young people of the time, was swept up in the romance of the Cuban revolution and what she saw as a socialist society. As she wrote, “The Cuba trip had been a great climax in my life.” (Davis, Autobiography, p. 215.) While a sharp critic of the United States, Davis was blind to Cuba’s problems at the time—the persecution of LGBT people, the persistence of racism, the dismantling of Black cultural organizations, the state’s control of the labor unions, and the complete lack of political democracy. Just as when she visited the GDR, as a Communist she saw everything in Cuba through rose-colored glasses.

When she got back to Southern California, she found herself embroiled in another controversy. She had received a one-year appointment as an assistant professor to teach philosophy at the University of California in Los Angeles, but Governor Ronald Reagan had pressured the regents of the university and the chancellor to fire her because she was a Communist. Rightwing activists were also demanding she be fired. She received hate mail and death threats and at that time her brother-in-law Ben was shot by the police and he and his wife Fania charged with murder. Shortly afterwards some 100 police surrounded the L.A. Panther offices, an event protested by a movement of thousands. Still, she toured the state organizing meetings on college campuses to defend her job at UCLA.

At the same time, she became involved in the movement to defend the Soledad Brothers, three men—George Jackson, John Cluchette, and Fleeta Domingo—accused of murdering a guard in Soledad prison. She combined organizing to defend her right to her job with demands that they be freed from prison. The Minute Men and the Ku Klux Klan appeared at her rallies and the continued to receive death threats. In the midst of those events, the Regents met and announced that they were not renewing her contract. Because of a court ordered injunction, they could not fire her for being a Communist. So, they justified not renewing her contract because she had given speeches “unfitting a university professor.” But as Angela later wrote in her autobiography, the truth was, “I had just been fired from my teaching position at the University of California by Ronald Reagan and the Regents because I was a member of the Communist Party.” (Davis, Autobiography, p. 6.) Now without a job, Angela returned to work on her dissertation, wanting to complete it so that she could look for another academic job.

On August 7, 1970 at a court hearing at the Marin County Civic Center for Black Panther James McClain, who had been accused of stabbing a prison guard, Judge Haley, who was also the judge in the Soledad Brothers’ case, was presiding. George Jackson’s 17-year-old brother Jonathan Jackson, carrying three weapons, attempted to kidnap Judge Haley in order to force Jackson’s release from prison. Jackson tossed one weapon to McClain and then gave another to another prisoner, Black Panther William Arthur Christmas. A witness in the McClain hearing, Ruchell Cinque Magee, went to free the other prisoners. Those four men then took five hostages, including the judge and the district attorney to a van waiting outside. As they drove from the courthouse, they were stopped at a roadblock a gunfight broke out and four people, including Jonathan Jackson and Judge Haley were killed, and three others wounded. Angela had not been present when these events took place.

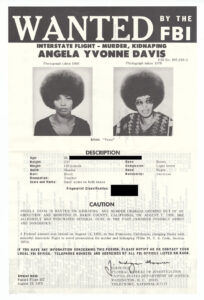

FBI Wanted Poster for Angela Davis.

Shortly after those events, a warrant was issued for the arrest of Angela Davis who had own the guns used in the courtroom attac. She fled secretly to Chicago where she met up with David Poindexter Jr., an under-the-radar Communist, who took her to Florida. Davis changed her appearance, cutting her famous Afro, and used false identities and then went to New York City. The FBI found her there at a Howard Johnson motel on October 13. She was charged as an accomplice to conspiracy, kidnapping, and murder and extradited to California for trial.

The Communist Party provided her with one of its most experienced attorneys, John Abt. The state introduced evidence that the guns used in the attempted kidnapping had belonged to Davis and that she had been corresponding with the men involved. During the long, drawn out legal proceedings, Davis spent 16 months in jail during which time the Communist Party and many other organizations created Angela Davis Defense Committees around the country and some spang up in foreign countries as well. Thousands around the country participated, many from churches. The Soviet Union and East Germany organized campaigns for her release as well. In 1971, John Lennon and Yoko Ono even wrote the song “Angela” for the campaign. Remarkably Abt and her other lawyers convinced the jury that she had had no knowledge of the events and had not been involved in planning them or carrying them out. Incredibly, on June 4, 1972 the all-white jury in Santa Clara County found her not guilty.

Once free Davis spoke in several American cities at large rallies of thousands celebrating her victory. Davis also visited Cuba, East Germany, and the Soviet Union where she also received praise.

When in the 1980s the Communists were considering candidates for national office, it is not surprising that they would have chosen Davis. First, “Angela Davis” had become a household name, known to millions of Americans, perhaps more than any other Communist since Paul Robeson. All of the events described here had constituted the daily news for years. True, many white conservatives reviled her, but she was admired by millions of young Blacks, Latinos, and whites. Second, Davis was an absolutely loyal Communist who never criticized the CPUSA, the Soviet Union, or other “socialist” countries.

Raised in Communist milieu, as an adult Davis was a dedicated member of the Communist Party, even if her rhetoric was sometimes more revolutionary than her party’s. She supported the Party’s domestic strategy, including its alliance with the labor bureaucracy and its tacit support for liberal Democrats. When Soviet tanks rolled into Czechoslovakia to crush the Prague spring reform movement, she supported the repression. And when in 1972, Jiří Pelikán, a leading Czech dissident wrote an open letter asking her to support Czechoslovak prisoners, she refused, arguing that the prisoners had been trying to overthrow Czech socialism. Nor would she support prisoners in the Soviet Union’s gulags. She taught in several California colleges in the 1970s and 80s, though found it difficult to advance her career. She similarly remained loyal to the Party and the Soviet Union even as Polish Marshal Jaruzelski, with Soviet approval, crushed the Solidarność labor union movement that was fighting for workers’ power and an end to the Communist state.

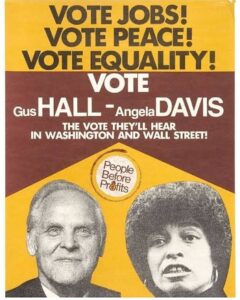

Davis’ loyalty to the CP led her in 1980 and 1984 to accept the party’s assignment that she be the running mate of diehard Stalinist party leader Gus Hall. A former lumberjack and steelworkers, Hall, who traveled to Moscow every year to be reconfirmed and reanointed by the Soviet Communist leadershi, had first become party leader in 1959. He had run for president in 1972 and 1976 with another Black vice-presidential candidate, Jarvis Tyner. In those two years the votes for Hall were few, respectively 25,595 and 58,99, miniscule percentages of the national vote. Though it ran its own candidates, the Communist Party permitted and even often encouraged its members and followers to work and vote for Democrats.

Angela Davis, as a veteran of SNCC and the Panthers, and famous for her trial and victory in the courts, should have helped the party. Yet, despite Davis’ fame, the CP’s vote declined from 43,871 in 1980 and 36,386 in 1984. As the New York Times wrote of Hall’s campaigns, “Mr. Hall’s message won few converts, and his four presidential campaigns, from 1972 to 1984, met with yawning indifference.” In all fairness, however, some Communists, many in the CP’s periphery, and many others who admired Davis, likely voted for Jimmy Carter in 1980 and for Walter Mondale in 1984 in order to stop Ronald Reagan’s Republican candidacies.

The Hall-Davis campaign, taking place as the social movements of the two previous decades had subsided and the country turned to the right, could not have advanced either the movements or the left. While they won more votes than Charlene Mitchell, the Hall-Davis campaign was a similar electoral fiasco. One has to wonder if the campaign might not have been more effective if Davis rather than the aging Stalinist bureaucrat Hall, had headed the ticket. Or if she had run as the candidate of the Black movement rather than the Communists

[1] I was at the time a graduate student in the Literature Department at UCSD and part of the local chapter of Students for a Democratic Society. At an SDS rally on campus, Angela Davis showed up with a column of Black and Latino students and said they were taking over the registration building and said that if we supported their demand to create a Lumumba-Zapata Campus, we could join them. Angela and the Black Student Council had never come to SDS to discuss their plan to take over the registration building, they simply told us to follow., Irritated that we in SDS had not been consulted from the beginning, I and my friend Helene Frances, stood at the door for a while before we too decided despite our objections to join the occupation. Once inside, the doors were barricaded, some students rifled through the files, and my friend Ran Mitra, who was close to Angela, came up to me and told me that some of her Black Panther friends form L.A. had also occupied the building and were armed. I thought that was something we should have been told before joining the occupation. The occupation only lasted a day; there was no violence and the administration punished no one.

Leave a Reply