The Long Deep Grudge: A Story of Big Capital, Radical Labor, and Class War in the American Heartland

The Long Deep Grudge: A Story of Big Capital, Radical Labor, and Class War in the American Heartland

Toni Gilpin

Chicago: Haymarket Books, 2020.

Seldom does an author deserve the praises heaped upon her book by the writers of promotional blurbs. Toni Gilpin and her Long Deep Grudge is the exception. With a light hand and the humor and drama of a novelist, the author tells the stories of generations of workers generally downplayed if not entirely ignored by historians and other communicators who favor the apparent “winners” in a society in which elite domination is assumed. In our historical moment of widespread discontent, Gilpin’s combination of balanced historiography, incisive analysis, and a touch of memoir produces a page-turner that shows, among other things, that history matters and that working people should learn their own history.

Gilpin, a member of Democratic Socialists of America, academic professional, and union activist, makes no bones about where she stands. She reveals from the outset her leftist family origins—her father’s Communist Party affiliation and lifetime commitment to union activism—and her own leftist, pro-labor sympathies throughout her adulthood. But as a rigorous historian, Gilpin nonetheless provides an acutely accurate account of the farm equipment industry—especially the International Harvester Corporation (Harvester)—and the workers and activists who produced its profits.

Crucial to the author’s analysis is a deep respect for the power of collective memory and the need to preserve it against the hegemony of the dominant forces that would erase from history the victories and the defeats of working people in order to persuade ordinary folks that “there is no alternative” (and never was) to the present system and its elites. Like her mentor David Montgomery and others, she recognizes the long history of workers’ efforts to resist the control and degradation of labor by employers’ sociopathic pursuit of ever-greater profit at the expense of those who create it. Collective memory shares the story with class identity and struggles within the agricultural equipment industry in the Midwest and in Kentucky. Gilpin explains how memory and class identity merged to create an ideology among leaders and members of a small but militant labor union, the United Farm Equipment Workers of America, that emerged in the 1930s in the Congress of Industrial Organizations (CIO), labor’s most dynamic coalition of the day.

But the author also anchors that success in the defining events of 1885-1886 in Chicago and their reverberation for several generations across time. After the clash over wage cuts between the McCormick Harvesting Machine Company’s president, Cyrus McCormick II, and the mostly Irish iron molders who labored in the foundry at the company’s McCormick Works, several other events followed. The inclusive organizing tactics of Myles McPadden of the National Union of Iron Molders gained the support of workers throughout the plant, mostly Germans, and routed an armed Pinkerton contingent, winning the strike. A determined but astute Cyrus II rescinded the pay cut, and all strike-breaking scabs were fired. Then the boss turned to retaliation: He soon installed automatic molding machinery and later got rid of McPadden. But labor was on the march in Chicago. Enter the anarchists.

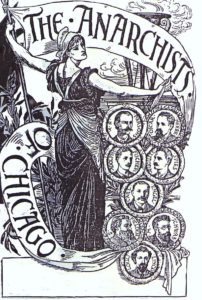

European radicalism melded with heartland ideals of freedom and equality and spawned the anarchists’ “Chicago Idea,” which held that radicalized labor unions could spearhead social and economic change, by violent actions if necessary. Soon, August Spies and Albert Parsons stood out amid would-be anarchist leaders, as an ever-more-militant movement arose in favor of establishing the workday as eight hours in length and the Knights of Labor expanded quickly as it promoted a general strike in support of that goal, come May 1, 1886. Gilpin states that at least 30,000 Chicagoans struck on that May Day, testifying to Chicago’s volatility, since no more than 200,000 turned out nationwide. The setting soon became volcanic.

A three-month lockout of workers led to a violent confrontation outside the McCormick Works in which police killed one man and wounded others. A protest rally called by the anarchists met that evening at Haymarket, near downtown, but was dispersing as a contingent of armed police approached the group and ordered them to do what they were already doing. As the police closed in upon the remnants, a bomb was thrown that landed among the officers; seven of them were killed by the bomb and by their panicked fellows. A wave of anti-immigrant and anti-radical vitriol burst over Chicago and much of the rest of the country, led by the commercial press, and a demand for revenge arose among the city’s “better circles.” In addition to the subsequent legal lynching of Albert Parsons, August Spies, and two others—none of whom was accused of throwing the bomb—the reactionary elements moved to suppress all dissenters. Renowned author and Atlantic Monthly editor William Dean Howells lamented that “this free republic has killed four people for their opinions.” In the following months and years employers, including Cyrus McCormick II, were to renege on their promises to enact the eight-hour day at their work sites and then suppress, lock out, and otherwise stifle working people.

This history helps us understand Chicago workers’ ongoing memories of a long tradition of repression, terror, and fraud by employers. Gilpin’s “ghosts of Haymarket” continued to inform the worker base in its future struggles. The McCormicks and their fellow employers suffered from their own specters in the early twentieth century. Louis Brandeis’s conversion of Woodrow Wilson to a union-friendly posture, government intrusions into the economy during the Great War, the Russian Revolution, and a renewed militancy of American workers produced great discomfort. Cyrus II himself lost a plant outside of Moscow.

Alarmed, corporate leaders created, in the wake of deep social disturbances of 1918-1921, the Employee Representation Committee, which appeared to the gullible to give workers a meaningful voice in the management of the enterprise. Workers at Harvester soon grasped the hoax. Later, the Great Depression showed that those who had claimed credit for the “permanent prosperity” of the 1920s could not escape blame for the collapse in the 1930s. Unions began to regain supporters. Secret meetings of Harvester’s Works Council members soon developed a de facto affiliation with the Communist-led Trade Union Unity League.

The left-led uprisings in Toledo, San Francisco, the textile South, and Minneapolis sparked enough concern among the elite that the next year produced the passage of the National Labor Relations Act (NLRA), the Social Security Act (including unemployment insurance), and growing support for unions. Harold Fowler McCormick, Cyrus’s son and successor, resisted these historic grains. But the radical core of workers at Harvester invoked the memory again of 1886, and this time they prevailed.

Gilpin dedicates most of her attention to the Farm Equipment Workers Organizing Committee (FE) after their successes of 1938. Gilpin cites the dozens of contractual work stoppages—but not official strikes—each year at Harvester plants despite labor’s “no strike” pledge during World War II. Not surprisingly, most stoppages occurred over piece-rate manipulations by management. “No strike” did not mean no struggle. The Greatest Generation were no pushovers on the home front.

The war was barely over when the United Auto Workers (UAW) began a practice that would badly weaken American labor. As corporations emerged from the war with unprecedented power and wealth, the UAW raided the FE in November 1945 and inaugurated intra-CIO cannibalism. As organized workers stood at the threshold of great power, the CIO began to splinter along political lines and made deadly rivalries a way of life. The U.S. labor movement still suffers from this split.

Gilpin relates and documents thoroughly the assaults upon the FE. Blows from the corporate right were expected, but from the progressive UAW ? Yes, but this first venture fell flat, as FE received 63 percent of the vote at the McCormick Works. The future did not look good, however, with the mighty UAW as an adversary. Yet, the FE decided in 1947 to contest the organizing of Harvester’s new plant in Louisville, opposing both the UAW and the AFL. Again, the tiny FE—never reaching 100,000 members—defeated the giants with a relentless person-to-person campaign by volunteers who encountered workers at the plant, at home, and at church with a straight-up anti-racist message. Then the Taft-Hartley Act, a union-hostile amendment to the NLRA, hit labor hard; the most bruising blow was Section 9h.

Section 9h held that no member of the Communist or Nazi party, or any organization advocating the forceful overthrow of the government, could serve as an officer in an American labor union and that all union officials had to take an oath that they were not members of such groups. Of course labor generally condemned the Taft-Hartley Act, which CIO president Phil Murray labeled “a slave labor act,” and counseled noncompliance; but AFL unions—except the United Mine Workers and the Typographical Union—complied, and CIO unions soon began to adhere to the law. After the FE lost a big Caterpillar local to the UAW (which had complied) because noncooperating unions had no standing at the Labor Board, the leaders signed the oath after several resigned their positions, a step that Gilpin implies was taken a little late.

Gilpin does not describe all 16 UAW raids against the FE, but she explains the reasoning of the FE leadership as they faced “The Shrinking Realm of the Possible” in 1948-1955. In 1948 the FE became the first union to endorse the Progressive Party candidacy of Henry Wallace for president, and it opposed the Marshall Plan. The FE leaders then sought strength in numbers and affiliated with the United Electrical Workers (UE), another Communist-led union, but Gilpin notes that the relationship remained uneasy, and the UE itself suffered heavy attacks from the UAW and the Steel Workers and AFL unions. After 1949 the CIO would fund a new International Union of Electrical Workers to destroy the UE. The writing was on the wall. The leaders discussed alternatives, and in 1955 they affiliated with their nemesis, the UAW.

Readers of Toni Gilpin’s The Long Deep Grudge will learn more than they’ve counted on and will enjoy the lesson very much—even the footnotes. Her account of a radical, democratic union of the past contains much that counts as a useable history.

Leave a Reply