Behemoth: A History of the Factory and the Making of the Modern World

Behemoth: A History of the Factory and the Making of the Modern World

Joshua Freeman

New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 2018

It is easy to forget the factory, especially for those of us in the “post-industrial” Global North. Few of us work in them—fewer than 10 percent in the United States. In our metropolitan conglomerations, the largest and most iconic workplaces are often conduits of consumption, such as warehouses and big-box stores; or bastions of business services, such as finance and information technology; or care suppliers, such as hospitals and schools. Factories rarely dominate the skylines of our cities and towns the way they once did. Given that five million of them disappeared between 2000 and 2016, we now think of factory jobs nostalgically, as good middle-class jobs that are never coming back.

Yet, as Joshua Freeman reminds us, factories remain essential to our lives. Virtually all our possessions come from factories: the furniture we sit and sleep on; the cars, buses, and trains we ride; the phones with which we communicate; the lamps that give us light; even the sheetrock that forms the walls of our homes. Factories have not disappeared. They have just moved. Worldwide, manufacturing is as large as it has ever been in terms of output and employment. And the biggest factories in history, measured by employment, are currently in operation.

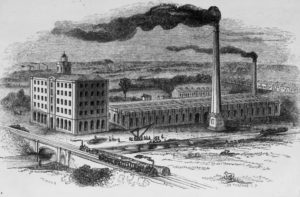

Freeman tells the story of the factory—and primarily the giant factory—since John and Thomas Lombe built the first silk mill in Derby, England, three hundred years ago. Each chapter explores a phase and/or location of factory development: England’s eighteenth-century “dark satanic mills,” New England’s “utopian” textile towns, the promise and peril of Promethean steel-making, the romance of Fordism, crash Soviet industrialization, Cold War mass production on both sides of the Iron Curtain, and the “hidden” behemoths of China and Vietnam.

As Freeman sees it, the factory is an essential foundation of modernity, in all its contradictions and its manifestations. It is a source of “miraculous productive power” and it has a “long history of exploitation.” It contributed to the overthrow of old agrarian orders, and it established new forms of industrial authoritarianism. It helped create the working class and it buttressed the bourgeoisie (or the “socialist” state). It inspired beautiful and celebratory modern art, and it provoked justified critiques of its monstrous deformities.

In telling the stories of large factories, Freeman deftly weaves together social, economic, labor, political, and cultural history. Thus, factories are not only buildings in which people work and products are made. They are economic engines that sustain life, social and cultural institutions that shape how people interact and see themselves, and political organizations that mold workers into citizens. Most crucially, they are sites of intense contestation in all these realms.

Retelling 300 years of world history through the lens of the factory has its costs and benefits. By bringing together historical developments from different places and times, Behemoth makes some fascinating comparisons, uncovering continuities and discontinuities that improve our understanding of factories no matter where or when. At the same time, hopscotching around the globe through three centuries means that Freeman can only outline answers to period- and location-specific questions. Thankfully, for most of those questions, Freeman’s stories, and his endnotes, offer good starting points to delve deeper.

Several themes course throughout Behemoth. One of those is size. Why do capitalists (and state bureaucracies) build such large factories and hire so many workers? There are multiple answers to that question, depending on such variables as the technology available, the structure of the market for the commodity produced, the relations between capital and labor, and the interests of the state.

The Ford River Rouge automobile complex was enormous in large part because it brought together in one place virtually all the activities—and worker skills—needed to produce an automobile, including the production of steel from iron and coal, the transformation of rubber into tires, the manufacture of glass, the fabrication of parts from those and other basic materials, and the final assembly of the car. In addition to economies of scale—spreading more production over a fixed set of plant assets—with control over each aspect of production, Ford and its workers could develop specializations and capture efficiencies at every point in the process. At its height of employment in 1929, the Rouge employed 102,811 workers, the most ever at one factory in U.S. history.

By contrast, Foxconn City in Shenzhen, China, had more than 300,000 workers in the mid-2010s, producing products such as smartphones, tablets, and laptops for companies such Apple, HP, and Dell. But unlike the Rouge, Foxconn produced few parts. Rather, it was mostly a final assembler in a global supply chain. It had short, simple, and labor-intensive production processes, using several dozen to a little over 100 unskilled workers to assemble each product. The complexity, and much of the value, was not at Foxconn; it was in the supply chain.

So, if the technical requirements of production did not involve more than six score workers, why did Foxconn employ hundreds of thousands of them? Just one reason: The customers demanded it. Apple, HP, Dell, and other “peak” corporations needed a single producer that could provide the volume their market dominance required. To meet the demand, Foxconn simply replicated its assembly process hundreds, even thousands, of times, with tens of thousands of workers doing virtually the same activities. Not coincidentally, as Chinese workers in large manufacturing centers such as Shenzhen and Dongguan began to protest their wages and working conditions, Foxconn and other manufacturers started to shift production to new facilities in the interior of China, or to Vietnam, where the price of labor was lower and the practice of collective action less prevalent.

The experience of factory work constitutes another theme Freeman explores. Foxconn and other Chinese manufacturers exploit cheap, plentiful labor, and, much like the New England textile mills of the early nineteenth century, that labor comes from the countryside. Whereas the mills hired mostly young women and some men from nearby family farms and housed them in local boarding houses, Chinese manufacturers hire young migrant women and men from the distant countryside and put them up in their own massive dormitories. Similarly, just as New England mill workers sometimes returned to their farms and sometimes embraced the delights of city life, Chinese workers sometimes return home to marriage and family and sometimes set down roots in rapidly expanding Chinese urban centers. This pattern of converting preindustrial populations into working classes has been a feature inherent in giant factories across time, space, and political economy.

Likewise, class conflict was and is endemic to giant factories. Freeman recounts the Luddite protests against early British mills, strikes in New England textile factories, the Homestead and 1919 steel strikes, and the unionization of U.S. basic industry in the 1930s and 1940s. In Freeman’s telling, class struggle plays a more central role in the development of factory relations in capitalist countries than in “socialist” ones. For example, in describing the crash industrialization of the Stalinist First Five-Year Plan, Freeman notes the use of forced labor but not the strikes, slowdowns, and demonstrations, as described by historians such as Jeffrey Rossman or Donald Filtzer, that also occurred during the period.*

Exactly why workplace struggle shaped up differently in Soviet tractor factories, British textile mills, Vietnamese shoe factories, or American steel plants is a question Freeman only hints at. We learn, for example, about the “common democratic vision” driving the strike of English-speaking white men in the Amalgamated Association of Iron and Steel Workers at Homestead in 1892. In comparison, the massive recent strikes of Vietnamese and Chinese workers come across as spontaneous, focused solely on bread-and-butter issues, without a larger vision of workplace power and democracy. Neither story is complete, and herein lies a drawback of such a sweeping history focused on a method for the organization of production rather than its social relations: It cannot capture the complexity, diversity, and historical specificity of the development of class consciousness to allow useful comparisons for historians and activists. But it does provide some hints.

Freeman uses different categories of analysis in different times and places. For example, state planning was no less important in Britain, New England, or Detroit for the development of factories than in Magnitogorsk, Nowa Huta, or Dongguan. Yet, Freeman stresses the state-level political contests that shaped “socialist” factories far more than capitalist ones. He delves deeply into the cultural movements that shaped or were shaped by the construction, operation, and interpretation of particular factories but not others. He stresses the relationship between factory and home life in New England textile mills, factory and city in Stalingrad, and factory and market in Shenzhen. Certainly, context matters, and the abundance with which Freeman provides it produces great insight into individual factories. The most interesting insights, however, come when Freeman transcends the context and carries the analysis across time and space, as in the comparisons of Foxconn’s operations with Ford’s or New England textile workers with Shenzhen electronics workers. With more theoretical consistency, there might have been more such insights.

Modernity is the one category Freeman consistently parades across time and space, but with few analytical results. As he admits, it is “a slippery term,” and, in Behemoth, it ends up meaning little more than the new and the now. Freeman does describe the contradictions of modernity—its horrors as well as its delights—especially as manifest in the giant factory. But if factories—and their cultural centrality—helped to make the modern world, indeed exemplified modernity itself, their absence must tell us something, too. Do we live in a post-modern world? Freeman doesn’t say.

Behemoth reviews the contemporaneous debates that accompanied the emergence of factories in different geographies and periods, and how those debates evolved over time. Time and again, new factories were celebrated for their innovative and transformative productive capacities: the efficiency of textile mills in Britain, the Promethean power of iron and steel mills in the United States, and the alleged vanquishing of scarcity embodied in Soviet factories. In almost every era, artists and writers from Anthony Trollope to Charles Dickens to Diego Rivera commemorated factories in paintings, poems, novels, photographs, and documentary films, and factories provided, at least for a time, an aesthetic that seeped into industrial, residential, and commercial designs of all types.

In some cases, ruling classes, and even workers, celebrated the new factories not just for the consumptive bounty they produced but for the workers and communities they created. Owners of early U.S. textile mills spoke paternalistically about the opportunities they offered women, who lived in well-run boardinghouses, joined churches, attended lectures, and enrolled in evening schools. One of first steelworkers organizations called itself the Sons of Vulcan and portrayed its members as the masculine, skilled, and powerful bearers of progress and civilization.

Similarly, early Soviet leaders, including Lenin and Trotsky, pushed, over objections from Left Communists and then the Workers’ Opposition, to adopt scientific management and Taylorism as means to transform peasants into the workers needed for rapid industrialization. Soviet leaders also built factory cities with worker housing, canteens, schools, recreation rooms, libraries, theaters, and clubs, all used to further inculcate peasants to modern “socialist” life. Likewise, for several decades after World War II, factories on both sides of the Iron Curtain delivered extraordinary improvements in pay, benefits, and security, providing the material basis to incorporate large portions of the working class into mainstream political culture, albeit with highly consequential racial and ethnic exceptions.

Eventually, and sometimes quickly, the admiration for factories faded, particularly as workers’ struggles emerged. British textile mills enjoyed no honeymoon, as the squalid conditions were evident from the start. The textile mills of Lowell, Massachusetts, lost their allure after several decades when competition increased, paternalism faded, the workforce changed from farm women to immigrant families, and strikes became more frequent. Artists of all types continued to celebrate the transformative power of factories through the turn of the twentieth century in monuments like the Eiffel Tower or the many exhibitions celebrating modern machinery and factory techniques. Yet, for critics such as Nathaniel Hawthorne, Joseph Stella, and Lincoln Steffens, iron and steel plants were just as dark and satanic as the first British textile factories two hundred years earlier. Likewise, just three years after Diego Rivera celebrated Ford’s River Rouge in the mural Detroit Industry on the walls of the city’s Institute of Arts, Charlie Chaplin produced Modern Times, a scathing critique of the dangerous, soul-deadening monotony of mass production and the exploitative system in which it was embedded.

In the Soviet Bloc, according to Freeman, working-class disillusionment with the factory came later and took a different form, so different that the factory had little to do with it. Sztálinváros, the Hungarian showcase steel-making city named after the Soviet premier, was a center of revolutionary agitation in 1956. Steelworkers left the factories to join the barricades in defense of the city against the Soviet Army, “a form of nationalist expression the planners of Sztálinváros had not anticipated.” After the suppression of the revolution, the new Communist leadership wooed steelworkers with wages and social benefits, and “a local socialist patriotism developed in the late 1950s and early 1960s, a sense of shared class experience and pride.”

The story in Nowa Huta (“New Mill”), Poland’s far larger and more successful version of Sztálinváros, was different, yet similar. Freeman calls Nowa Huta “arguably the last Stalinist utopia.” The mill, begun in 1950, grew in stages over decades, eventually encompassing five hundred buildings, but it is the city around the mill that draws Freeman’s attention. Characterized by a “distinct urbanism” and a human scale, the city had largely self-sufficient neighborhoods built around apartment buildings with stores, health centers, and libraries. Cinemas, restaurants, and public institutions were within walking distance. “The social organization in effect constituted a more fully realized, if less radical, embrace of communal life along the lines of the earlier worker housing in Gorky.”

The conflict in Nowa Huta in its first decades was cultural, between former peasants and the Communist authorities struggling to shape them into law-abiding and docile workers. The problems were rowdiness, alcoholism, brawling, sexual assault, and venereal disease. With economic development, these problems receded, but another cultural challenge emerged: Catholicism. Nowa Huta workers demanded a church, defended public installations of religious crosses, and built networks of mobilization to press for both.

Economic struggle finally emerged in the 1970s, mostly in response to price hikes, still drawing on the networks built to promote Catholicism. A price increase in July 1980 led to an explosion of strikes, and workers in Nowa Huta won concessions from management, leading 90 percent of them to leave their official union and join Solidarity, founded recently in the Lenin Shipyard in Gdansk. The declaration of martial law at the end of 1981 led to near-constant and mostly clandestine struggle, with Nowa Huta workers linking up with the largest industrial workplaces in the country to form a network of organizations.

Bringing together thousands of workers, the steel mill facilitated Solidarity’s organizing, but was not itself a site of protest until 1988, when, in response to yet another price increase, workers, their families, sympathetic priests, and outside Solidarity leaders occupied the complex. After three weeks, soldiers ousted the protestors. Nonetheless, the occupation sparked a strike at the Lenin Shipyard, which, a year later, led to open elections, triumph for Solidarity, and the end of Communist rule in Poland. As Freeman describes, it was a Pyrrhic victory, since the political struggle did not transform social relations in the plants, which, due to years of underinvestment, were unprepared to withstand the rigors of capitalist competition.

Though Chinese Communists briefly tried to replicate the all-encompassing experience and triumphalism of Soviet factories and suffered many of the same setbacks, few celebrate the giant factories of post-Deng China the way authorities and acolytes celebrated the wonders of Magnitogorsk or the Rouge. Instead, Chinese leaders view Foxconn City and factories like it as a stage through which the country must go to reach modernity.

Surveying their 300-year history, Freeman concludes, “Giant factories have a natural life cycle”: explosive growth with intense exploitation of previously nonindustrial workers; incremental improvement or stagnation due to the constraints of fixed capital and competition from newer, more technologically advanced rivals; rising worker protest and wages; and the need to modernize, start over elsewhere, or shut down. That the largest factories are now in China and popping up in Vietnam illustrates just how often factories must “start over elsewhere.”

Freeman also concludes that the factory has played the same role with only minor differences no matter in which political economy it was embedded. “Yet, as this study shows, to portray the giant factory as strictly a capitalist institution requires eliding much of its history, including some of the largest factories ever built. The giant factory was central to both capitalist and socialist development, not only economically but socially, culturally, and politically as well. … The giant factory, rather than a feature of capitalism, turns out to be a feature of modernity, in all its variations.”

In one sense, this conclusion lessens the explanatory power of the factory. Its ubiquity renders it banal, irrelevant to explaining the success of Solidarity or the failure of the Homestead strike, and inconsequential in defining strategies for democratizing the economy. In another sense, the factory’s existence across political economies—its hierarchical organization of production, its exploitation of people and the planet, and its politically incorporating role—says something profound about the class nature of both capitalist and “socialist” societies. And about the need to transform them.

Leave a Reply