Review: Thomas Sakmyster. A Communist Odyssey: The Life of József Pogány / John Pepper. Budapest-New York: Central European University Press. 2012. Photos. Bibliography. Index. 249 pp.

Review: Thomas Sakmyster. A Communist Odyssey: The Life of József Pogány / John Pepper. Budapest-New York: Central European University Press. 2012. Photos. Bibliography. Index. 249 pp.

During normal times in a capitalist society, skill and drive are harnessed by the corporations, the labor union bureaucracy, and the political parties, but when the crisis comes a revolutionary party must harness the most talented and most ambitious for its purposes. The idealistic and the opportunistic, the selfless and the self-aggrandizing, the ruthless and the kind, the brave and the cowardly among those most determined and striving souls must somehow be made use of for the higher purposes of the revolution and ultimately for of all of humanity. The revolutionary movement must bring out the best in them, for we are the only material we have.

The great European revolutionary epoch of the post war period from the 1910s through the 1920s provides endless biographical material revealing all that is best and worst in the human material of revolution, the Russians having been the most studied, providing shelves of biographies of Lenin, Bukharin, Stalin, and Trotsky. Among other figures of the era from various countries we also have remarkable women like Clara Zetkin, Rosa Luxemburg and Alexandra Kollontai and men such as Grigory Zinoviev and Karl Radek, all of them with their strengths and weaknesses. If perhaps Victor Serge represents the most idealistic and heroic, then József Pogány, also known as John Pepper, embodies all that is the most opportunistic and morally reprehensible. Yet he too under the impulse of revolutionary forces and within the structures of what was for a while a revolutionary organization made his contributions.

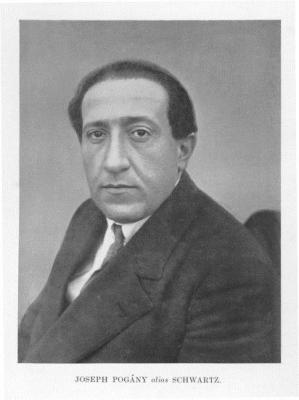

Pogány/Pepper—who like other Communists of the era used several other pseudonyms as well—remained something of a mystery until now. Before this book, Hungarian historians knew of József Pogány who had been a major figures in the Hungarian Revolution and the Americans knew John Pepper who had played a key role in the American Communist Party, but now we have the full picture of this fascinating figure in a highly engaging and illuminating biography. My former colleague at the University of Cincinnati, now Professor Emeritus, Thomas Sakmyster, a scholar in the area of international relations, Communism, and Hungary, making use of Hungarian, Russian and American sources from the archives of the Communist International to the records of the FBI, as well as the memoirs of Pepper’s wife and many other papers, has produced the first comprehensive biography of Pogány.

And a great story it is. A Social Democratic and then a Communist leader in the Hungarian Revolution of 1918-19, Comintern agent in the German Communist March Action of 1921, and a central leader of the American Communist Party in the 1920s, arrogant and opportunistic, Pogány stirred up controversy wherever he went. The words most commonly used to describe him, writes Sakmyster, were “loathed,” “detested” and “reviled.” Yet he also won the favor of top Communist leaders such as Zinoviev and Bukharin, charmed and captivated audiences of soldiers, workers, and leftists, had a tremendous career as a writer, and, despite his philandering, never lost the love of his wife Irén. What makes such a man? How does a person so difficult also remain so influential? Why was he tolerated for long? And what eventually brought him down?

Pepper was born in 1886 as József Schwartz, the son of a middle class Jewish family. Jews in Hungary faced less discrimination than in other European countries, and József was able to attend the prestigious Barcsay Gimnázium and then go on in 1904 to the University of Budapest. At the age of 17 he changed his name to Pogány, a name with a Hungarian ring to it, though it means “pagan or heathen” and may have been his way of breaking with Judaism and all organized religion. At the university he studied Hungarian and German language and literature at a time when Hungarian literature had become a call progressive change. He, his friend Ernő Czóbel and his sister Irén Czóbel, became involved with a group of radical students, began reading Népszava (The People’s Voice), and subsequently secretly joined the Social Democratic Party of Hungary, secretly because the government forbid students joining political parties. As part of his studies Pógany spent six months in Berlin and six months in Paris, attending some classes but spending more time with the labor movement and the socialist parties before returning to finish his dissertation on the Hungarian poet János Arany, graduating summa cum laude. Having earned his doctorate, Pógany married Irén Czóbel in 1909.

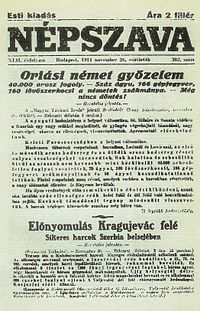

After finishing his studies, Pógany wrote for Munka Szemle (Labor Review) and Szocializmus (Socialism) and the newspaper Friss Újság (Fresh News) as well as the most influential Hungarian magazine of the day Huszadik Század (Twentieth Century). He wrote from a Marxist perspective on literature, history, current events, contemporary social problems, particularly the lives and conditions of working people. With his friend Czóbel he joined the Demokrácia Lodge of the Masons, putting him in touch with other progressive intellectuals. In 1912 he was proud to become a writer for the socialist paper Népszava, the dream of every young radical. He soon became an editor writing on political issues and especially on foreign affairs. During the period from 1912 to 1914 he was a sharp critic of the Austrian Hungarian Empire. One of his articles attacking the Austrian Hungarian imperialism led to a trial—where he was also accused of lèse majesté—and sentenced to six months and jail The outbreak of World War I saved him from serving any time.

Jozsef Pogany became a writer for Népszava,

the Hungarian socialist newspaper.

Though Pogány had written editorials strongly criticizing Austria Hungary for its imperialistic policies in the spring and early summer of 1914, when the war broke out he aligned himself with the Social Democratic Party leadership, supporting the war and a truce in the class struggle for the duration. Drafted, he served in combat alongside the German forces against the Russians, suffering a serious chest wound. Once well enough to work again, he became a correspondent for Hungarian, German and Swiss commercial and socialist newspapers, some of his articles being published as pamphlets during the war. He cultivated relationships with the military officers and he opportunistically self-censored his own pieces, going so far as to celebrate Austrian Hungarian military campaigns and victories over Russia. On the other hand, Pogány focused much of his writing on the ordinary infantry soldiers who endured the brunt of the battles, sympathizing not only with Austrian-Hungarian and German soldiers, but also the Russian and Italian enemy soldiers.

During early 1918 Pogány followed closely the events in Russia where workers and soldiers had created soviets (councils), and the Bolsheviks had taken power under the leadership of a virtually unknown figure named Lenin. By January of 1918 workers in Budapest were engaging in large scale demonstrations and some workers and leftwing socialists called for revolution, but Pogány warned that without support from the peasantry and the other nationalities and, in particular, without support from the soldiers a revolution would be doomed.

By October 1918 the Habsburg Empire was collapsing, strikes were spreading, street demonstrations a daily occurrence. Dual power developed, with the Habsburg monarchy being challenged by a National Council made up of the renegade Count Mihály Károlyi, the Radical Party, and the Social Democratic Party. Pogány opposed the SPD participation in the coalition government but he had little chance of influencing its decisions. Following his “political instincts,” Pogány began to agitate among the rank-and-file soldiers. “In fiery speeches, sometimes seven or eight a day, he urged the soldiers to repudiate the hated Austro-Hungarian army, which he denounced as a tool of the capitalists and imperialists.”

After the king appointed Károlyi prime minister, he in turn appointed Pogány the commissioner to the Soldiers’ Council upon which the National Council government depended. At the same time, Pogány continued his agitation among the soldiers, telling them to refuse to be disarmed and to maintain their discipline in the face of provocation. The soldiers, seeing they had a champion in Pogány, elected him president of the Soldiers’ Council. As both commissioner and president Pogány called for the election of officers and purge of counter-revolutionaries. When on more than one occasion the National Council government attempted to limit and reduce his power, Pogány responded by mobilizing the soldiers in street demonstration and marched on the Buda castle and succeeded in bringing down two minister of defense. His resolute actions won him the support of the left wing of the SDP and made him a significant political figure.

The situation became more complicated in November of 1918 when Béla Kun arrived in Hungary coming from Russia with former prisoners of war who had been converted to Communism. While this new Communist Party was small it was also quite active. Its cadres agitated at factories and in street demonstrations, distributing their newspaper Vórős Úsjág (Red News), and winning support from both the left and from the poor. The CP’s presence also “exacerbated differences among the factions of the SPD,” now divided between those who supported the Károlyi government and those who were increasingly critical of it.

Some SPD leaders such as Győrgy Lukács, a leading leftwing intellectual, quit and joined the Communist Party. Communists and SPD dissidents were now holding secret meetings. Pogány initially resisted Communist overtures, but by March 1919 he had become an advocate of an alliance between the SDP and the Communists in Hungary and on an international scale between Hungary and Russia. With other leftwing SPD members he voted for merger with the Communists. Having helped to negotiate the merger of the parties, he raced to the Soldiers’ Council to put forth and pass a resolution calling for a government of the newly merged Socialist Party and for the dictatorship of the proletariat. The new party took power.

Béla Kun, leader of the Hungarian Soviet Republic

The Hungarian Soviet Republic lasted only 133 days with Béla Kun as head of state and Pogány serving both as Commissar for War and as a member of the five-man executive committee of the Revolutionary Governing Council. Forced to resign as Commissar for War, he was later appointed a minor military commander and finally made Minister of Education. Pogany was a strong advocate of an alliance with the peasants. He argued that the government should give up its attempt to collectivize agriculture and instead distribute land directly to the peasants. His position might have made a difference, but it was too late. The Hungarian Soviet Republic was disintegrating. When the Western powers presented the Clemenceau Note to the Hungarian Soviet Republic demanding that it cede the territory that its Red Army had recently conquered, Kun recognized that the government would have to acquiesce. The Hungarian Communist revolution had been defeated. On August 1, 1919 the Revolutionary Governing Council turned over power to the moderate Social Democrats who had sat out the revolution. Kun and other Communist leaders left Budapest by train for Austria eventually reaching Vienna.

By August 1920, Kun and Pogány had arrived in Moscow to put themselves at the service of the Communist International (the Comintern). While still in Vienna Pogány had written a book on the counterrevolutionary government in Hungary titled The White Terror that, translated into German and Russian, enhanced his reputation among Communists in those countries. In Moscow he met the Russian revolutionary leader Grigory Zinoviev, worked as an assistant to the German Communist Karl Radek, was sent to Vienna to participate in a Comintern conference on the Balkan countries, and then dispatched to the Southern Front in the Crimea where the Red Army defeated General Wrangel’s forces. Back in Moscow where Trotsky and Lenin were debating Zinoviev on the need for a “breathing space” in the ongoing post-war revolutions, Kun and Pogány sided with the latter. Pogány was the most ardent advocate of continuing the revolutionary drive.

When in February of 1921 the Comintern decided to send a delegation to Germany, it included Kun and Pogány. Ordered by Radek not to “let slip a decisive moment,” Kun and Pogány pushed for a revolutionary rising and found themselves in conflict with Klara Zetkin and Paul Levi who urged caution. On March 23, at the urging of Pogány and others, the action went forward despite a last minute attempt by the German Communist Party to call it off in Hamburg and Central Germany. The March Action, unsupported by the majority of German workers, led to thousands of casualties and to mass resignations from the Communist Party. When Kun and Pogány returned to Moscow, they were criticized and privately reprimanded by Lenin and Trotsky for their adventurism. Nevertheless, they continued to be advocates of the revolutionary offensive. During this period, Trotsky and Pogány developed a mutual contempt that only grew deeper over time.

With not only Trotsky but also Radek tiring of his irascible behavior and knowing that he had to find a new project, Pogány offered to go to the United States as a representative of the Comintern, though his exact role remained unclear throughout his American stay. The American Communist Party of 1922—known at the time as the Workers Party—was small, only about 6,000 members, many of them immigrants organized in foreign language federations of Italians, Poles, Finns and so on. Pogány soon reorganized the Hungarian Federation and refurbished its newspaper Új Előre (New Forward) which he was soon proud to call the leading leftwing Hungarian newspaper in the world.

At the same time, since he was seen as the Comintern representative, Pogány was soon a major figure in the Workers Party, speaking in German which was understood by many Communist leaders and members. They called him the “Hungarian Columbus” for he had discovered America. Within a year he had taught himself English well enough to deliver speeches, to debate and to write articles and pamphlets. Now, using the name John Pepper, he was able in English to express himself with the usual sarcasm and vitriol for which he was so well known and so disliked. He put forward positions that were central to the transformation of the Workers Party over the next several years, arguing that American Communists had to learn to speak English, to create an aboveground political party, to work to organize a broad labor party, and to become advocates of the rights of Negros.

Pepper was everywhere. He helped to create the Daily Worker and to make it into a genuine socialist labor newspaper for which he wrote frequently, as he did for the party monthly The Liberator. He wrote a pamphlet For a Labor Party that argued in popular language for the creation of a working peoples’ party in America. He became a member of the Central Executive Committee and secretary of the Political Commission, as well as a member of the Secretariat, three powerful positions. Not surprisingly he was soon referred to as the “Czar and commissar” of the party. There was hardly an aspect of the Workers Party upon which he did not have an impact, and generally for the good.

Yet Pepper can also be held responsible in large part for the greatest debacle of the American Communist movement’s early years, its role in wrecking the attempt to create a labor party in the early 1920s. At the time, the Chicago labor movement was led by militant unionists Edward Nockles and John Fitzpatrick. They had led organizing drives among packinghouse and steelworkers in Chicago and William Z. Foster, a leader of the Communist Party, had worked with them. They had created a Chicago Labor Party in 1918 and then an Illinois Labor Party in 1919, part of the broader Farmer Labor Party movement, and were now attempting to create a national labor party. The Communists wanted to participate and Fitzpatrick was willing to let them, but told them up front, “Let’s get the record straight—we are willing to go along, but we think you communists should occupy a back seat in this affair.”

Pepper saw the organization of a labor party as a major breakthrough and wanted the Communists to be in the front seat, if possible in the driver’s seat. He soon overcame the caution of the Communist leadership and persuaded them to take an aggressive role. He used every trick he had learned in the European and American socialist movements to artificially increase the Communist Representation to the founding convention held in July 1923 in Chicago, so that when it began, out of 550 delegates, about 190 were Communists who with their effective floor leadership and discipline were able to play a leading role. Communists made up a majority of the new party’s executive committee and controlled the party journal. Furious, Fitzpatrick withdrew as did most of the labor unions that had been involved. As a St. Louis labor newspaper later wrote, “Workers’ Party Captures Itself and Adopts a New Name.”

During his first stay in America, Pepper had become embroiled in heated faction fights. He was aligned with Charles Ruthenberg and Jay Lovestone against a faction that included William Z. Foster and James P. Cannon among others. The conflict in the American Communist Party was like other issues at the time to be settled in Moscow, so after two years in the United States, Pepper—once again Pogány—returned to the Soviet Russian capital in time for the Comintern’s Fifth World Congress. Through Zinoviev’s good offices, Pógany was appointed to the Political Commission and presented its theses on the economic crisis as well as speaking on revolution in China and criticizing the British Communist Party’s position on the Labor Party. The Congress adopted Zinoviev’s “Bolshevization” program and Pogány was sent to Sweden to implement it there in August of 1924. Back in Moscow, Pogány became director of the Comintern Information Bureau and a member of its Negro Commission.

Pogány was at the height of his influence at the Comintern in 1926. He spoke before the Comintern executive on international labor. He wrote for the newspaper Pravda and journal Imprecorr. He served on the American Commission and became secretary of the British Secretariat and in that role wrote the pamphlet The General Strike and the General Betrayal. He worked closely with Zinoviev on the campaign against Trotsky, but when Zinoviev fell from favor, he transferred his allegiance to Bukharin and Stalin. Privately he commented, “Just now I’ve discovered that…I’ve been kissing the wrong ass!”

Yearning to become a Comintern agent in China where he saw a revolutionary future, he worked to become an Asian expert, becoming a member of the Japanese Secretariat and of a commission on China, but his plans backfired when he was sent to Korea, referred to as the “graveyard” of Comintern agents. Afraid of traveling in disguise to Korea, he went instead to Tokyo, Kobe and Yokohama as well as Shanghai, and though he met with Korean Communists in those cities, he never carried out his assignment to meet with Korean Communists in Korea. Returning to Moscow he filed a false report claiming he had visited and met with Koreans in Seoul, a report that later came to haunt him.

Fearing that his prevarication would be uncovered, he was anxious to flee Moscow and once again asked to go to the United States. Permission was granted in February and by mid-March 1928 he was back in New York where he quickly made himself the expert on the American Negro Question, becoming chair of the Negro Commission and in that capacity setting up the American Negro Labor Congress (ANLC). He rejected the idea of self-determination for the black population, believing that African Americans wanted “equal rights for all nationalities and races.” He argued that the Communists should “fight for the Negroes as an oppressed race.” Pepper also became an advocate of the theory of “American exceptionalism,” that is, the notion that the theories and policies being applied by the Comintern in Europe did not necessarily apply to the United States. Little did he realize that his positions on the Negro question and American exceptionalism would be his undoing.

At the Sixth World Congress of the Comintern held in Moscow in July and August of 1928 Pogány found himself under attack from Stalin and his group for his theory of American exceptionalism, but many others piled on as well. He quickly shifted his position on the Negro Question, rejecting the slogan of equal rights for self-determination and saved himself from abuse there. He returned to the United States and actually ended up drafting the party pamphlet American Negro Problems which remained an important CPSU publication for several years and continued to be consulted for decades after. But, though he seemed to be once again back in the swings of things, the game was up.

In January 1929 he was ordered to return to Moscow and forbidden to attend the Workers Party convention but decided to say in the United States. He told the American Communists that he was going to Moscow, but hid in an apartment in New York in order to continue directing the Lovestone faction. At the same time, he became embroiled in love affairs with two of his secretaries, one of whom had a jealous boyfriend. When Pogány finally returned to Moscow he told the Comintern leadership that fearing the U.S. authorities were on his trail he had gone to Mexico, but then decided not to take the ship from there and returned to the U.S, which was why he had been delayed. Meanwhile the true story of his hiding out in New York and his love affairs had come to light. The executive committee of the American Communist Party expelled him, but later rescinded the expulsion, arguing that that should be left to the Comintern.

When he arrived in Moscow in April, he was excoriated by Stalin and his group for his theories of American exceptionalism and his position on the Negro Question. Expelled from the Comintern in the summer of 1929, he was put to work in the Soviet bureaucracy until his reinstatement in the Comintern in May of 1932. Once again he spoke, wrote and translated furiously and made a name for himself, while on important matters he echoed the opinions of Stalin and vilified Trotsky and Bukharin. But he had no real future. He had not only offended Stalin, but too many others as well. Finally in July of 1936 his time came. The secret police arrested him and he was imprisoned as were his wife and daughters. On February 8, 1938, Pepper was tried, convicted, and shot. After Khrushchev’s revelations of Stalin’s crimes at the Twentieth Party Congress in 1956 Pogány was posthumously rehabilitated.

Pogány’s political life was marked by a series of major disasters: the Hungarian Revolution, the March Action, and the Labor Party fiasco in the United States. Yet at the same time, his fundamental program for the Workers Party—Americanization, building an aboveground party, creating a broad labor party, and fighting for Negro rights and equality—represented the necessary steps to create real left party in the United States. The revolutionary forces of the period and the Communist Parties, however, proved unable to harness Pogány. He was one of the ambitious ones whose egotism makes them unable to work collectively and to contribute to the common cause. Ultimately as Sakmyster writes, the combination of Pogány’s vanity and arrogance and the transformation of the Communist Party into Stalin’s dictatorship came together in such a way as to destroy him. We should remember that the revolutionary movement that produced Pogány/Pepper also produced Victor Serge and many other noble and idealistic men and women for whom the building of a democratic socialism was more important than either their own personal careers or the demands of Stalin’s bureaucracy. In any case, we have to go forward, for we are the only material we have to work with.

Leave a Reply