Amidst so much to read and digest about events in Charlottesville and Trump’s response to them, and what seems (but is not) a new, highly violent emergence of neo-Nazis, the KKK, and white supremacist organizations, this blog by Adam Shatz on the website of the London Review of Books seems to me one of the more eloquent, insightful analyses. I share it with NP readers. Lois Weiner

Amidst so much to read and digest about events in Charlottesville and Trump’s response to them, and what seems (but is not) a new, highly violent emergence of neo-Nazis, the KKK, and white supremacist organizations, this blog by Adam Shatz on the website of the London Review of Books seems to me one of the more eloquent, insightful analyses. I share it with NP readers. Lois Weiner

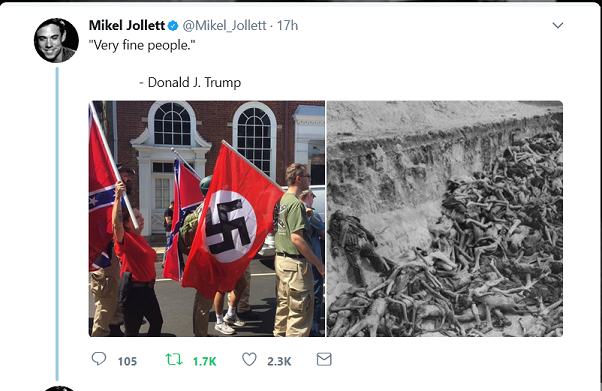

Trump set them free

In late July, HBO unveiled plans for a new show set in an alternative reality, in which the Confederate South, led by General Robert E. Lee, has successfully seceded from the Union. D.B. Weiss, one of the producers of Confederate, explained the thinking behind the series: ‘What would the world have looked like if Lee had sacked DC, if the South had won – that just always fascinated me.’

Last weekend in Charlottesville, Virginia, Weiss got his answer, with the ‘Unite the Right’ demonstration against the planned removal of Lee’s statue in Emancipation Park (formerly known as Lee Park). This ‘gallant scene of the pastoral South’, as Billie Holiday might have described it, was open to anyone who hated black people and Jews (‘Jews will not replace us’ was one of the cries), from members of the Ku Klux Klan to neo-Nazis. Emboldened by having an ally in the highest office in the land, they came with Confederate flags, swastikas, medieval-looking wooden shields, torches and, of course, guns. They came to fight. One young woman in the counter-demonstration was murdered by a man who rammed his car into her, weaponising his vehicle just as jihadists have done in Nice and London. A helicopter surveilling the event crashed, killing the two officers inside. Dozens were injured.

For the next two days, the world waited for Trump to denounce those responsible for the pogrom. The week before, he threatened North Korea with nuclear incineration (‘fire and fury’). Trump is so hollow a person, so impulsive a leader, that it’s easy to miss the great paradox of his presidency: that a cipher of a man has revealed the hidden depths, the ugly unmastered history, of the country he claims to lead.

The ‘Unite the Right’ protest was a reminder that the dream of the Confederacy has never died: the vision of Herrenvolk democracy has continued to smoulder since Union troops left the vanquished but still defiant South, scarcely a decade after the end of the war. Eric Foner has described the Reconstruction era, when ex-slaves became citizens and the first biracial southern governments were elected to power, as America’s ‘unfinished revolution’. The battle over Reconstruction never ended; it has simply changed forms. And the struggle to achieve full enfranchisement for black people in the South has produced many martyrs: Medgar Evers and Martin Luther King; James Chaney, Michael Schwerner and Andrew Goodman. And now Heather Heyer, the 32-year-old paralegal killed in Emancipation Park.

It is true, as some have sanctimoniously pointed out on Twitter, that even in her death, Heyer was a beneficiary of white privilege, remembered as a ‘strong woman’, rather than subjected to the invasive background check typically meted out to unarmed black people killed by the police. But her biography suggests that she would have been the first to object to any special treatment. ‘If you’re not outraged, you’re not paying attention,’ she wrote in her last Facebook post. She broke up with a boyfriend who expressed unease over her friendship with a black man, her manager at work. White supremacists have reserved a particular loathing for white women in the civil rights struggle: ‘nigger lovers’, they call them. One white woman at the counter-demonstration reported a jeering fascist as saying to her: ‘I hope you are raped by a nigger’; Heyer is likely to have heard similar things. For white supremacists, the end of white rule has always meant the conquest of white women by men of colour, from the rapacious emancipated slaves in Birth of a Nation to Trump’s immigrant ‘rapists’.

The man charged with Heyer’s murder, James Alex Fields Jr, a 20-year-old from Ohio, fits the usual terrorist profile: a radical loser without a father, intelligent but semi-educated and isolated, drunk on visions of grandeur on the stage of history. His murder weapon was a car, rather than a gun, but he was cut from the same cloth as Dylann Roof, who shot dead nine worshippers at a church in Charleston two years ago. Fields wrote school papers celebrating the Third Reich and shouted racist curses at home, but neither his teacher nor his mother thought to report on his ‘radicalisation’. Even if they had, the government is unlikely to have cared. In February, the Trump administration announced that it would no longer investigate white nationalists, who have been responsible for a large share of violent hate crimes in the United States; the focus of the ‘countering violent extremism’ programme would be limited to Islamist radicals. White nationalists were exultant. ‘Donald Trump is setting us free,’ the Daily Stormer website crowed.

When Fields set off for Charlottesville, he told his mother he would be attending a rally for Trump, which wasn’t entirely a fib. David Duke, the former Imperial Wizard of the Klan and a former Louisiana state representative, whose endorsement Trump could hardly bring himself to disavow, said that Unite the Right was intended to ‘fulfill the promise of Donald Trump’.

The fascists in Charlottesville are a fringe, not a mass movement, but they are a coddled fringe: hence Trump’s initial attempt to blame ‘many sides’ for the violence, as if victims and perpetrators inhabited the same moral plane. The fascists represent the hard edge of the coalition that brought him to power, and they express, though in a cruder form, the ideology of his advisers Steve Bannon and Sebastian Gorka. When – under apparently intense pressure from his aides – Trump finally denounced white supremacists as ‘evil’ in a speech read off a teleprompter, he sounded like a little boy forced to eat his spinach, or to rat on his friends. No president has been so easily flattered, so thrilled by the sight of his own name, which his advisers include in policy memos in order to hold his attention. To repudiate a follower is not only to threaten his electoral base, as Bannon surely counselled him; it is to threaten the supply of adulation that is Trump’s lifeline, and the only thing, aside from loyalty to Trump, that he has raised to a principle.

James Comey discovered the costs of betraying this ‘loyalty’; and so has Kenneth Frazier, the head of the pharmaceutical company Merck. On Monday, Frazier – one of America’s most prominent black executives, the son of a janitor who, unlike Trump, can reasonably claim to be a self-made man – resigned from a presidential business council in protest at Trump’s response to Charlottesville. Within less than an hour, even as he continued to withhold any condemnation of the perpetrators, Trump was on Twitter: ‘Now that Ken Frazier of Merck Pharma has resigned from President’s Manufacturing Council, he will have more time to LOWER RIPOFF DRUG PRICES!’

Trump’s Republican allies have scrambled to denounce the violence, in ever more pious tones, while falling far short of withdrawing their support for Trump. Listening to Paul Ryan, John McCain, Marco Rubio, Ted Cruz and Orrin Hatch inveigh against the evil of white supremacy, you might have thought they’d just dusted off their copies of Between the World and Me. They can hardly claim to have been shocked by Trump’s response, however. As erratic as Trump has been, he has been remarkably consistent on the question of race. He cut his teeth in a real estate firm – his father’s – that was investigated by the FBI for not renting to blacks. In 1989 he took out an ad in four newspapers, calling for the execution of five young black and Latino men charged with raping a jogger in Central Park; even when the ‘Central Park Five’ were exonerated 25 years later, he insisted on their guilt. He built a campaign on the claim that Obama was not American, appealing to the oldest prejudices about black American rights to citizenship. He has revelled in the idea of police brutality.

What, then, explains the florid paroxysms of Republican anti-racism in the face of Charlottesville? The purpose is not to expunge white supremacy from American life, but to expunge its naked expression, which Trump, to their embarrassment, has been reckless enough to encourage. Since the Nixon era, Republicans have understood that the party’s plans to favour the white ‘silent majority’ depend on coded language that everyone understands but which can be plausibly denied. Cruz and Hatch may be distressed by Trump’s response to Charlottesville, but neither of them objects to his policies on race, which amount to the most far-reaching assault on civil rights since the Voting Rights Act was signed into law in 1965. His attorney general, Jeff Sessions, whom the New York Times has hailed as a ‘forceful figure’ for his comparatively forthright condemnation of the violence, has led these efforts. He has reduced the civil rights division of the Justice Department, promised to end oversight of police departments, and proposed relaunching the drug war that helped lead to the scandal of mass incarceration. His idea of a ‘civil rights investigation’ is to investigate cases of discrimination against white students in universities, or – Trump’s favourite – claims of ‘voter fraud’ in the 2016 presidential election, a flagrant attempt to suppress the vote among blacks and Latinos who supported Hillary Clinton.

During the election, Trump’s attacks on Muslims, undocumented immigrants and other non-white people were portrayed by some members of the press as a kind of rhetorical extravagance: the lurid expression, like his tower and his casinos, of a tabloid clown. The implicit suggestion was that his racism needn’t be taken too seriously, and that it wasn’t, in any case, the major reason for his popularity. A number of prominent liberal intellectuals – in a move that suggested self-flagellation but was closer to racial blindness – claimed that if Trump was popular, it was because of liberal condescension to the fabled white working class. The identity politics of the left, they suggested, was driving misunderstood and maligned blue-collar workers into Trump’s arms. As it turned out, Trump’s support among whites ranged across class lines, and was particularly strong among middle and upper-middle-class whites. They were driven into his arms by identity politics – their own. They understood, and welcomed, Trump’s promise to make America great again, for what it really meant: to make it white again, and to take back the White House from a black president.

Yet the spectre of a black president continues to haunt the White House, not least in Trump’s imagination. In his most revealing, because least rehearsed, response to Charlottesville, Trump said that racism ‘has been going on for a long time in our country – not Donald Trump, not Barack Obama. It has been going on for a long, long time.’ Trump often invokes Obama, not least when he is trying to dismantle national healthcare: like a security blanket, the name ‘Obama’ seems to provide Trump with a sense of mooring. Still, this was a curious remark, coming from someone who has had little patience for history or the longue durée, and who had rather strongly implied that if America had a race problem, it was Obama’s doing. One possible interpretation of this cryptic (and typically ungrammatical) statement is that Trump could hardly be expected to end racism, when the country’s first black president, of all people, could not: a back-handed, and racist, compliment to his predecessor. Another is that Trump remains perversely fixated on the figure of Obama, aware that without him, and without the anti-Obama backlash he spearheaded, he would not be president.

Adam Shatz

August 15, 2017

Leave a Reply