This is the first part of an article about the new politics in America today.

The presidential election campaign of 2016 represents a turning point in American politics, raising issues and political agendas that would have been unthinkable in the United States only a few years ago. The major media and the public debate whether or not Republican Donald Trump is a fascist, while at the same time there is a discussion about whether Democrat Bernie Sanders’ version of democratic socialism is the answer to the country’s problems. Trump’s political rallies have, at his instigation, become violent and he now threatens to send his followers to disrupt Sanders’ rallies.

These new political developments have deep historical roots going back to the 1960s, and they are arising principally a result of the decline of American hegemony internationally, a series of economic crises culminating in the deep economic crisis of 2008, the growing economic inequality in American society, and the failure of the major parties and establishment candidates to respond to the needs of middle class and working class people. The development of this new politics in America leads us naturally to ask: What in our society has led to this change? How significant is this new politics really? And what are its prospects for the future? And what can we do to bring about a better future of democracy, equality, and justice? For there is a radical alternative to these developments.

The primary elections in both the Republican and Democratic parties have seen the emergence on a mass scale of political ideologies and social movements that until now had remained largely submerged. Ideas that were unthinkable in the past and virtually beyond discussion in mainstream society are now everyday topics. Bernie Sanders’ campaign has raised a far-reaching, progressive economic program aimed at recouping the position of the country’s working people while also initiating a debate about the previously taboo topic of socialism, a subject that has not been raised in the general public in the United States since the 1940s.[i] Sanders speaks a language unheard for decades, referring to the American “ruling class,” “the billionaire class,” and the need for a “political revolution.” He calls for rebuilding the labor movement and Labor for Bernie attracts thousands. What is most novel about Sanders is that his campaign questions not only the current administration, but—in part through its adoption of the term “socialism”—implicitly questions capitalism, just as his call for a “political revolution” questions American democracy.

At the same time, Donald Trump’s xenophobic remarks about Mexican immigrants and proposals to exclude Muslims from the country—until now part of the lexicon of fringe rightwing racist groups—not to mention his quoting Benito Mussolini and failing for days after being asked to dissociate himself from David Duke of the Ku Klux Klan, have led to a debate among politicians and in the media about whether or not Trump is a fascist whose speeches—including incitement to violence–are encouraging the development of a fascist movement in America.[ii] Trump’s program of economic nationalism, the call to end the trade treaties and to stop shipping American jobs abroad finds a positive response among workers, including many labor union members.[iii] Not since the 1930s has one seen in America large-scale debates over the meaning of socialism and fascism, and perhaps never anything quite like this at the national presidential level. We have a new politics in America.

What’s taking place is not simply the one-off appearance of flamboyant, outlandish, or quirky candidates. Nor is it a fluke of this election. We are at a real turning point in contemporary American political life. A new American right and left have been incubating in our cities, suburbs, and rural areas for decades, engendered by earlier social upheavals and economic crises and born under the impact of the 2008 Great Recession. Since the end of the post-war’s Golden Years, a series of recessions—in 1975-75, 1979-82, 1990-91, 2001, and then the Great Recession of 2007-2008—have battered the notion of American exceptionalism, the myth of America’s economic invulnerability, and the fantasy of permanent capitalist prosperity. The recessions disturbed the comfort of the American middle class and whittled away at the standard of living of American workers generally, while pushing millions of whites, Blacks and Latinos into poverty. If before we were dreaming the American Dream, we are now wide-awake.

The result of the return of regular recessions to the American economy beginning at the end of the 1960s, after the relatively smooth growth of the thirty Golden Years, brought about a long, slow, but growing political polarization. A Pew Research Center report found recently that, “Republicans and Democrats are more divided along ideological lines—and partisan antipathy is deeper and more extensive—than at any point in the last two decades.”[iv] The report discovered that the American people have become more ideologically consistent, sorting out into opposing camps, and consequently have less in common with each other. “As partisans have moved to the left and the right, the share of Americans with mixed views has declined.”[v]

A New York Times article described the situation: “Twenty-seven percent of Democrats and 36 percent of Republicans see the other party as a threat to the nation’s well-being. Consistent liberals and consistent conservatives, those who hold nearly uniform liberal or conservative beliefs, are even more alarmed: 50 percent of consistent liberals and 66 percent of consistent conservatives see the other party as a threat to the nation.” The Times article notes that Americans are now so divided that they would prefer to live in like-minded communities and would rather not have their children marry someone of the opposite camp.[vi] Americans are separating, pulling apart, and facing off.

While the far left argues convincingly that the Republicans and Democrats represent what are fundamentally the same capitalist system and more specifically the same politics of economic austerity, at the same time it is also true that on many important issues—abortion rights, regulating firearms, labor unions, tax policies, immigration, affirmative action, social welfare programs, and questions of a religious versus a secular society—the two parties have quite different and often diametrically opposed positions. And while economic crisis and class issues may be driving the development of a new politics, it is race issues, especially the position and role of Black people in American society, that are often at the heart of the increasingly polarization. Working people’s declining incomes and growing economic insecurity may drive the process of political change, but race is the flashpoint of the conflict.

Political polarization is both an expression of and the result of the changing racial make-up of the country, and the voting patterns of racial groups. Political scientist Alan L. Abramowitz writes in The Washington Post:

Today, the Republican electoral coalition remains overwhelmingly white. Nonwhites made up only 10 percent of Romney voters according to the 2012 national exit poll. But the nonwhite share of Democratic voters has increased fairly steadily since the 1960s and that trend has accelerated since 1992. Nonwhites comprised 45 percent of all Obama voters in 2012, and a majority of Obama voters under age 40.[vii]

Abramowitz concludes his article with the observation that, “The deep partisan divide in Washington clearly reflects a deep partisan divide within the American electorate, and for this reason, it is unlikely to diminish any time soon.”[viii] That is, there is not only a polarization in Congress, but also a political polarization in society, and it is one that is based fundamentally on issues of class, race, and gender. This new political situation has its roots in the radical changes that began to take place in America more than forty years ago and culminated in the 2008 Great Recession. And while it is often the so-called social issues that divide left from right in mainstream America, class issues are often at the root of things.

Starting with the Sixties: Black Movements and White Backlash

The starting point for understanding the new politics in America will be found in the late 1960s and early 1970s with two developments coincided that fundamentally changed American society.[ix] The first was the Civil Rights movement, followed by Black Power, lasting from 1955 to 1975, while the second was the opening of a financial crisis that began in the late 1960s and reached its nadir in the economic recessions of 1974-75 and 1979-82, definitively ending the post-war Golden Years. Each of these developments contributed to the reconfiguration of American politics in the succeeding decades, slowly producing a new right and a new left, a process that continues to unfold today.

The Black civil rights movement in the South between its beginning in Montgomery, Alabama in December 1955 and President Lyndon B. Johnson’ signing of the Civil Rights Act in 1964 upended racial politics in the South and unsettled things throughout the nation. As Bill Moyers remembered, “When [Johnson] signed the act he was euphoric, but late that very night I found him in a melancholy mood as he lay in bed reading the bulldog edition of the Washington Post with headlines celebrating the day. I asked him what was troubling him. ‘I think we just delivered the South to the Republican Party for a long time to come,’ he said.”[x]

At the same time, the civil rights movement’s frustrations with de facto racism and economic inequlity, especially in the North, gave rise to the Black Power movement, which was accompanied by the urban riots, and ghetto rebellions, destroying many of the country’s inner cities. The Black riots and rebellions accelerated white flight to the suburbs and provided justification for the tremendous white backlash that was already taking place. Many conservative whites of all social classes in all sections of the country became opponents of all that they identified as in any way Black: affirmative action, social welfare, and equal opportunities in employment and housing.

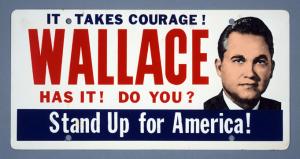

Quite naturally the white backlash against the Black civil rights movement began in the South and in the Democratic Party. In 1968, George Wallace, a four-term governor of Alabama, one of the leading fighters for racial segregation, and a hero to many white southerners, decided to leave the Democratic Party (temporarily) and run as an independent candidate for the U.S. presidency. He established the American Independent Party and chose as his running mate U.S. Air Force General Curtis LeMay who had played a major role in directing the bombing of Japanese cities and civilians during World War II. LeMay was an advocate of the strategic use of nuclear bombs and had come into conflict with President John F. Kennedy when he wanted to drop atom bombs on Cuba in 1962. Later LeMay suggested that nuclear bombs might also be used in Vietnam. Wallace’s program called for defending segregation in the South, increasing Social Security and Medicare, and getting out of the Vietnam War if it could not be won—presumably by LeMay’s methods—within 90 days of his assuming office. Wallce and LeMay represented both a throwback to Old South’s fight against Reconstruction, but also an anticipation of a new right that would emerge in the 1980s.

Wallace lost, but it was the most successful third party campaign in modern American history. Republican Richard Nixon won the election with 31.7 million popular votes and 301 electoral votes; Democrat Hubert Humphrey got 30.9 million popular votes and 191 electoral votes. But Wallace, better than any other third party candidate before or since, won 9.9 million popular votes, carrying five southern states, and receiving 46 electoral votes. (By comparison, John B. Anderson’s Independent Party campaign in 1980 and Ralph Nader’s Green Party campaign in 2000 carried zero states and got zero electoral votes.) Most important Wallace’s campaign, demonstrating the political power of alienated Democrats, spelled the end of the old Solid South of the Democratic Party and opened the way to the Republican’s Southern Strategy.

Over the next two decades, Southern whites left the Democratic Party en masse and became Republicans, a Solid South once again, but now as Red States. The ghetto rebellions led many northern, city-dwelling and especially suburban Democrats to move into the Republican Party as well. The country simultaneously underwent a re-segregation, as Blacks and whites, channeled by realtors into different neighborhoods, went in increasing numbers to separate (and because of tax laws) fundamentally unequal city neighborhood or suburban schools. The cities—having become largely Black, Latino, and immigrant—largely stuck with the Democratic Party, while the white suburbs and rural areas tended to become Republican strongholds. The roots of the contemporary racist and reactionary Republican Party, as well as the rightward drift of the Democratic Party and the emergence of the Blue Dog Democrats in the 1990s must be found in large measure in the white backlash of the 1960s and 1970s.

The Black movement’s impact in that era was not simply in the area of race relations—it affected virtually every aspect of American society. The Black movement, as we know, opened the door to two decades of social protest, from 1956 to 1975. The Black movement for civil rights, legitimating social protest after the McCarthy era of reaction and repression, also made possible the anti-Vietnam War movement and the women’s movement, and the three together drove a wedge deep into the heart of America, separating much of the younger generation, some young white workers, many Blacks and Latinos, as well as a good many urban left liberals from the more conservative, white, suburban world. Blacks, Latinos, and women—and later gays and lesbians—demanded, fought for and won greater rights and power, while straight white men in particular experienced a loss of status. While males’ resentment against this loss of power and prestige in their homes, on their jobs, and in society became a powerful driver of the new right movement. As minorities and women challenged patriarchy and white power, middle-class and working-class white men felt increasingly under attack and many reacted by turning away from the Democratic Party.

Thanks to my friends Dave Finkel, Rusty Gilbert, Joanne Landy, Bob Master, and Kim Moody for their suggestions. I alone am responsible for the views expressed in this article.

[ii] http://www.nytimes.com/2015/12/03/opinion/campaign-stops/is-donald-trump-a-fascist.html?_r=0; http://www.cnn.com/2015/11/24/politics/donald-trump-fascism/ ; http://www.cnn.com/2015/11/24/politics/donald-trump-fascism/ ; https://newrepublic.com/minutes/124205/yes-donald-trump-fascist

[iv] http://www.people-press.org/2014/06/12/political-polarization-in-the-american-public/ See also another PEW report on polarization at: http://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2014/06/12/7-things-to-know-about-polarization-in-america/

[v] http://www.people-press.org/2014/06/12/political-polarization-in-the-american-public/

[vi] http://www.people-press.org/2014/06/12/political-polarization-in-the-american-public/

[vii] https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/monkey-cage/wp/2014/01/20/how-race-and-religion-have-polarized-american-voters/ Polarization also reflects a sharp division over religions, as Abramowitz observes: “By 2012, 69 percent of white voters who reported attending religious services at least once per week identified with the Republican Party compared with only 41 percent of white voters who reported rarely or never attending religious services—the largest divide ever recorded. Some 75 percent of religiously observant whites voted for Mitt Romney in 2012 compared with only 46 percent of non-observant whites.”

[viii] https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/monkey-cage/wp/2014/01/20/how-race-and-religion-have-polarized-american-voters/

[ix] The argument I advance in this section is hardly original. Others, for example Ruy Texeira and Alan Abramowitz, have made a similar case: http://www.brookings.edu/~/media/research/files/papers/2008/4/demographics-teixeira/04_demographics_teixeira.pdf

[x] Bill Moyers, Moyers on America ( ), p. 167.

Well done!

Thanks Dan, Really tight analysis and very readable. I admit feeling a sense of dread knowing the direction of the next segments in your series. I will share on FB. All the best to you and Sherry…

Mike McCleese Worcester, Vermont