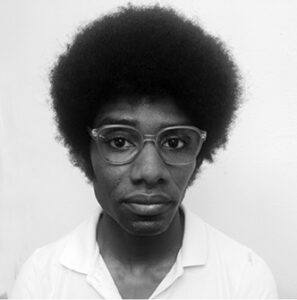

Khury Petersen-Smith (KPS) is the Michael Ratner Middle East Fellow at the Institute for Policy Studies in Washington, D.C. He researches U.S. empire, borders, and migration. Phil Gasper (PG) spoke with Khury on behalf of the New Politics editorial board on April, 12, 2022.

Khury Petersen-Smith (KPS) is the Michael Ratner Middle East Fellow at the Institute for Policy Studies in Washington, D.C. He researches U.S. empire, borders, and migration. Phil Gasper (PG) spoke with Khury on behalf of the New Politics editorial board on April, 12, 2022.

PG: Great to talk with you, though not in the greatest of times looking at the global scene. I thought we’d start with Ukraine because that’s dominating the headlines at the moment. You’ve written some interesting pieces about what is going on, the background and so on. In one of them you argue against binary thinking by the left in terms of the war in Ukraine.1 Can you explain what that means and what you think the right framework to understand what is happening should be?

KPS: Absolutely. I think we have this problem where the nation-state is the only political container that we’re able to think in terms of. And that is true in general and it’s true of the left. I mean, the nation-state is powerful and so there’s this gravitational pull to align with one state or another, particularly when states pose themselves as rivals. And so, when it comes to binary thinking, it’s painfully the case with the situation in Ukraine. Russia has one story of what’s happening—that this is about a response to Western aggression. Then the United States and NATO have another story, which is that they’re intervening on behalf of Ukraine in defense of Western values, which are universal values, and Russia is attacking those things.

On the left, there’s been this pull on both sides. I’ll locate myself in this conversation in the U.S., though it’s not limited to the U.S. people who want to stand against U.S. empire say—well there’s a pull to say—well, I guess in rejecting the U.S. line, I have to accept or excuse or apologize for or downplay what Moscow’s doing. Then on the flip side, there are people on the left who would, in other circumstances, be critical of U.S. power, but in light of Russian aggression, they say, well, I guess the U.S. is actually doing the right thing. And not only doing the right thing, but their story makes sense—this is an attack on Western values, this is an attack on international law.

The truth is, I would argue, that both of these states are part of a world system in which they abuse the rights of people for the pursuit of power on the world stage. And, actually, one of the difficult things about the Ukraine crisis is that there’s this 24-hour conversation about it that in many ways is very important, but it’s informed by a memory of, like, six weeks. If you just take a step back and look at how the U.S. and Russia have exercised power on the world stage, both have done horrendous things. And there have been plenty of times when they’ve joined each other in doing horrendous things. Russia and the U.S. actually collaborated after the 9-11 attacks in the early days of the War on Terror. The U.S. and Russia famously collaborated during World War II—they were on the same side, and they were on opposing sides, and they got together again. So, this notion that there’s this binary world where Russia and the U.S. represent entirely polar opposite points of view and behaviors is just false. And I think that an internationalist orientation is one that begins, first and foremost, with a solidarity with ordinary people and people resisting oppression, and that is always skeptical of state power as a starting point, particularly for the world’s most powerful states.

PG: Can you say a little bit more about the background to the current crisis, the current war? You mentioned what both sides say. How much of that is correct? Is it a case where both are correct when they’re criticizing each other?

KPS: That’s a good question. After the end of the Soviet Union and the end of the Cold War, that was one moment in which the U.S. was the world’s sole superpower, it wielded tremendous power on the world stage. Then there was another moment, after the September 11th attacks and the beginning of the War on Terror, where it became clear that there was this kind of trajectory toward the development of multiple world powers and a set of questions about who would be the most powerful states in the world and how they would rule. For seven decades, the U.S. was able to not only wield power directly, but craft all of these institutions of global governance with the U.S. at the head of the table—craft all of these laws, these rules of commerce, and essentially play an enormous role in structuring the world economically and politically and socially. And so, there was a question about, in the 21st century, will that still be the model? And if so, which states will preside over it?

I went back to the national security strategy document of the Bush administration in 2002, because I remembered that document spoke to the emergence of what Washington called potential peer competitors—potential rivals to U.S. power. I remember in that document a mention of China and of Russia. Upon rereading it, what was fascinating was, I had forgotten that India is in there as well. And so, Washington actually identified three potential challenges to U.S. power, Russia, China, and India. What was also striking were the glowing words for Russia. It was about how Russia is on its path to democratization after the end of the Cold War, that there was growing cooperation between the U.S. and Russia. And so, the U.S. welcomes a rise of Russia if it can proceed along this path. So that’s an interesting kind of background to where we’re at today. And I think two things worth noting have transpired. One is that the U.S., in an effort to really secure its position as the world’s number one superpower, made a massive gamble called the War on Terror, in which they invaded several countries in a row, launched military operations across whole regions of the world in an effort to project U.S. power in the few places where it didn’t yet dominate, and make sure that the U.S. reigned supreme. The War on Terror has been a catastrophe for humanity. The U.S. state also really lost the gamble. The U.S. is not more powerful twenty years later, the U.S. is relatively lower in power.

Russia, meanwhile, has been projecting power in its own way. In particular, around the same time, 1999-2000, Russia was carrying out a massive war in Chechnya that was atrocious and horrendous, which was about Russia re-establishing its power in the region. You could put its operations in Georgia [in 2008] in that same category. And then, very significantly, Russia intervened in a massive way in the Syrian civil war. The Middle East has historically been considered for a century by the world’s powers as the most strategic place in the world. The U.S. was hoping to dominate the Middle East with its War on Terror and it was actually set back. And Russia was able to step in, and I think that’s what its intervention in Syria was about.

So, I actually see that as the path to bring us to the Russian invasion of Ukraine. I mean, there’s a conversation about Russia’s historic attachment to Ukraine, and Putin has a kind of ethnic nationalist vision, and there’s truth in that. But this is about Russia establishing itself as having the right to call the shots in the region, first in this sort of post-Soviet region, the region that it dominated under the Soviet Union, then increasingly in the Middle East, and now in Europe. That’s Putin’s gamble—Russia should be a political player in Europe (it’s already an economic player). And I think that’s what this war is about in so many ways. The frame that this is about an attack on Western values and universal values—I don’t think that that holds up as an explanation of what’s going on.

PG: So, there’s big power politics behind this and their shifting relative strengths, because China is in the background of this—of the conflict in Ukraine—as well. I think you’re right, the U.S. gambled in the early part of this century, and while it’s still the biggest military and economic power, part of its gamble was to try and maintain total hegemony, and that clearly is not the world that we’re living in today. So, in many ways, it’s less stable and more dangerous than, certainly, 25 years ago. Part of the background, as well, has been the expansion of NATO in the post-Soviet era, and you’ve written about that too.2 So, could you bring that into the story?

KPS: Well, there’s a couple of things to say. NATO which is a military alliance whose pretext was collective self-defense of North Atlantic nations in the Cold War. Well, the Cold War ended, and NATO not only remains but has expanded. So, the pretext is false. I mean, the idea that it’s a defensive alliance is false. It is a military alliance for projecting Western power in a way that’s led by the United States. There’s a sort of formal NATO alliance. It also has these other projects that involve countries beyond Europe and North America. So, it’s really a kind of U.S.-led western military alliance with global reach.

That said, there has been a question in Washington of the utility of NATO. This alliance, which was part of the architecture for the kind of post-World War II Pax Americana, U.S., empire—is this still useful to us? I think that that question is bound up in a set of questions about the utility of these multinational formations in general, militarily, politically, and economically. Is the UN still useful to us? Are these trade deals still useful to us?

The greatest expression of that kind of questioning in Washington was the Trump presidency. There was a section of the U.S. elite that said, let’s try something different. Yeah, we’re still number one. Our profits are pretty good, but they’re not as good as they once were. We still have a lot of power, but don’t have the relative power that we once had. And we may not be able to secure this forever. So, maybe we should try something new. And Trump said, I’ll try something new. Forget about NATO. I’m going to thumb my nose at NATO. I’m going to go to NATO convenings and mock people in NATO. I’m going to confront NATO states for not doing their fair share. The U.S. has shouldered the burden for too long and it has hurt U.S. power. And that is a pretty central piece of the Trump narrative—that the U.S. playing this role, not solely for itself, but structuring the whole world around U.S. power and therefore taking responsibility for that world order, is no longer serving us. And actually, other countries have taken advantage of our generosity. And therefore, maybe we should leave this alliance. So, that was a debate in Washington.

Of course, others, particularly in the Democratic Party, and its main stewards of U.S. empire—Hillary Clinton and Barack Obama, Madeleine Albright—are dedicated to NATO. So, there was a bit of a debate. Well, the debate is over. I think with the war in Ukraine there is a level of unity in Washington on the outlook of U.S. empire, unseen in a long time. And I think that there is unity behind NATO as, yes, this does remain a useful vehicle for us to maintain the kind of world order that we want.

PG: And the shift is visible in Europe as well, because now it looks very likely that NATO is going to expand further—Finland, possibly Sweden, joining it. And there’s definitely been a shift towards more belligerence. Germany is now on board for doubling its military budget. At the same time, the U.S. military budget is being jacked up even further. You could see NATO expansion in the post-Soviet era as a real provocation to Russia. But Putin’s response, by invading Ukraine, has actually brought about what he claimed that he didn’t want to see, which is a further expansion of NATO. I have to say that before the war started, I didn’t think Putin was foolish enough to actually invade. I thought his strategy was to build up on the border and exacerbate the differences that existed within NATO. And it was very clear that there were some pretty sharp differences between the UK and the U.S. on one side, and Germany and perhaps France on the other side. And those have now, at least for the time being, disappeared. There’s now unity between the European and the U.S. ruling classes. And it looks like it has created an even more dangerous situation than existed prior to that.

KPS: I think you’re absolutely right. I mean, I also didn’t expect the invasion because, like I said, I thought that the goal has been Putin being a political player in Europe. And just by amassing troops at the border, he achieved his goal. He got meetings with Macron He got a meeting with Biden. He established himself as a player. And so, my thinking was Putin got what he wanted. Why would he go for more? But he too made a gamble. And I think it’s a gamble where, again, the people paying the massive price are the people of Ukraine, but at the moment, Russia is not winning the gamble. The war is not going the way they thought.

But the other thing is there has been a polarization, a further polarization, a kind of geopolitical polarization that has done exactly what you said. It’s consolidated the Western powers in a kind of alliance. This is another part of the binary geopolitical frame that’s really built into the whole thing. And I think, just on the final word on the question of NATO, there were these questions in Washington about is this the vehicle to achieve our goals. I think there have been questions throughout Europe about any number of [similar issues]. Is the European Union the vehicle? The UK leaves—they say we’re thinking this is not the vehicle, we need some other arrangement. What we’ve seen just in a matter of weeks is that a number of long-term goals that these states have all had, have been able to be achieved in the context of this crisis. It has settled the question for them.

The U.S. wanted a bigger military budget. They’ve been making the case particularly using China as the kind of justification. But they got it with Russia. Germany, which has historically had these limits on the amount of military spending and how it spends, that’s over. They’ve crossed a line. Denmark, same thing. I think there’s a real kind of dark celebration, actually, in the Capitol in Washington, in Ottawa and Berlin and Brussels, because in the context of this war, they’ve been able to achieve these long-term goals of advancing power.

PG: So, the big picture is that we have to keep all of this in mind. This is a competition between a whole number of powers, which sometimes come into alliance with each other, and sometimes have greater antagonisms. But the central dynamic is the growing conflict between the U.S., Russia and China, and how that plays out.

For the time being, it looks like the U.S. doesn’t want to get directly militarily involved [in Ukraine]. Far too risky. We are talking about the U.S. and Russia still being by far the two biggest nuclear powers. We don’t know that that line is not going to be crossed, because it’s often not through direct intention, but just through the accident of the tensions which build up. But for the time being, the U.S. response has been sanctions on Russia. You’ve written about that too.3 And I wonder if you can talk a little bit about sanctions because you’ve criticized the sanctions which the U.S. and European countries have put in place on Russia. And I’d also like you to talk a little bit about this in the context of other kinds of sanctions. Because while many on the left have criticized the sanctions on Russia, many of us also have been supporters of the boycott, divestment, sanctions movement to pressure Israel. Some people have thought that there is a contradiction here or a tension of some kind. Can you talk about the sanctions in that context too?

KPS: Absolutely. First, just a word about why the U.S. is not yet engaging directly militarily. And I think what you said is true, the risk is enormous. The other thing is that the U.S. is achieving its political goals without having to do that. I mean, it’s like Washington at the moment has all the benefits that it reaps from a war without actually having to send troops into combat. I mean, you’ve got a wartime president whose approval ratings has went up. You’ve got this huge ideological boost—the idea that the U.S. is a force for good in the world, that its allies are a force for good. They’ve got their bigger military budget. So, they’ve already won, and they don’t need, from their perspective, to take the risk of combat.

Now sanctions. The U.S. has used sanctions for many years as one tool in its arsenal to advance U.S. power, whether we’re talking about the U.S. sanctions on Iraq in the nineties, the U.S. sanctions on Cuba, which have existed for several decades, the sanctions on Iran, on Venezuela, on North Korea. So, Washington frames sanctions—and unfortunately a lot of people accept this frame—as an alternative to war. We’re not going to invade, we’ll just use sanctions. But the truth is the impact of sanctions has historically been as devastating as military operations. In Iraq and at the moment in Iran, the impact of U.S. sanctions is absolutely catastrophic, especially in these past couple of years with the COVID pandemic.

So, there’s the impact of sanctions. But then the other thing is that far from being an alternative to war, the U.S. has actually used sanctions with military operations. And so, the sanctions on Iraq—it’s like the U.S. invades Iraq in 1991, it imposes sanctions in the nineties, and invades again in 2003, bombing intermittently over the course of the sanctions-regime, through the no-fly zone that the U.S. maintained. So, it’s not sanctions or war, it’s sanctions and war. That’s one reason why we should just be skeptical.

The other thing is the impact has entirely predictably been on the most vulnerable people of Russia. When the Ruble crashed, those are the people who suffered—ordinary people, especially the most vulnerable of the ordinary people, poor people, people with disabilities, people with illnesses, who are now struggling to access medicines and things like that. There are reasons to oppose sanctions in the moment because of their impact on Russian people, which is totally unfair. It’s impacting people who are not responsible for this war.

The other thing that I’m very concerned about, though, is that the U.S. is using this to re-legitimize sanctions in general. So, people who have been questioning the U.S. sanctions on Iran, and who maybe would oppose U.S. sanctions in other contexts, have said, well, in the case of Russia, maybe it’s okay. With that new boost of legitimacy, the U.S. will deploy its sanctions apparatus against other countries too. It won’t stop with Russia. I’m just concerned about the kind of legitimizing of U.S. power in general. At the moment, the main face is sanctions, as well as the sale of weapons.

Now, on the question of Israel, it’s interesting because if we ask people “What do you mean by sanctions?”, different people will say different things. It’s an incredibly broad category. All it means is that there should be accepted norms, and ways of doing things, and rules that apply to global political life. And that if a country deviates from or violates those, sanctions are a kind of response. They’re a punishment. The kind of sanctions that we talk about when we talk about sanctioning Israel, which is in violation of international law, and there are all sorts of other violations that it commits—it behaves in ways that violate what should be acceptable in a global society—for the most part, particularly for those of us located in the United States, we’re talking about stopping the cooperation of U.S. institutions with the Israeli administration of apartheid, particularly the sale of weapons. Usually when you ask people, “What do you mean when you say sanctions against Israel?”, it means stop the U.S. military aid. That is a different measure than the kind of sanctions being used against Russia.

When we’re talking about sanctions against Israel, or when I’m talking about sanctions against Israel, I’m not talking about making ordinary Israelis suffer, like wrecking the Israeli economy. But also, the U.S. has a very different relationship with Israel than it does with Russia. So, if the U.S. was selling Russia weapons, I would support ending that. That’s not the situation, but that is the situation with Israel. And so those are the sanctions that we support.

PG: So, there are sanctions and sanctions. In general, sanction just means some kind of punitive response—something that recognizes the violation which has taken place and tries to correct it. I want to talk to you also about the refugee aspect of the current crisis, because this is a topic you’ve written about extensively. And it brings out some of the huge hypocrisy. You talked about the U.S. using this as an opportunity to present itself as a force for good in the world. But if you look at the refugee crises around the world, Ukraine is not the worst. There’s a massive refugee crisis in Syria, of course, and Yemen, where the U.S. continues to support the Saudi war on Yemen—a huge humanitarian crisis there, including several million displaced people. There’s, of course, the refugee crisis on the U.S. southern border, or the so-called crisis—but clearly there’s an issue about how refugees are treated. Can you put all of that into context for us? Both the ways in which the U.S. has approached this from a very hypocritical position, but also what the response should be to growing refugee issues around the world.

KPS: Absolutely. This is important. The first thing that has to be said is, of course, Ukrainians have the right of freedom of movement and the right to refuge, the right to be relocated to countries where they’ll be safe and where they can start new lives for the moment. They have that right because everybody has that right—all displaced people have that right. And one of the things we’re seeing, of course, [is that] millions of people have been displaced within Ukraine and from Ukraine by the Russian invasion. Among the people displaced is quite a significant number of Africans, who’ve been studying in Ukraine or otherwise living in Ukraine, who are in no less a desperate situation than Ukrainian nationals, and you could argue in more of a desperate situation actually, because they have more complicated legal status, [and are] more vulnerable. And we’ve seen, on one hand, Ukrainians received by neighboring countries and Africans facing discrimination at the hands of officials in those neighboring countries, as well as Ukrainian officials. That is an injustice in and of itself. But it’s also a window onto the global situation of displacement and refugees, which is one in which tens of millions of people are displaced beyond their home countries and there is stratification in terms of how they’re received, the rights they have, the lives that they are expected to be able to live. And that is a racist stratification.

You named a number of situations. One that it’s important to put on the table is the refugee situation of Palestinians. It’s significant not only because all refugee populations are significant, and not only because it’s a large population of refugees—it has been the largest number of refugees in the world—but also because Israel and its allies have made Palestinians the test case of permanent refugeehood, which is actually a feature of this world. There’s this expectation that Israel has normalized, that Palestinians will never be able to return to their homes. Not only Palestinians today, but generations of Palestinians will be refugees. Israel has pioneered that. The U.S. has helped cement that notion and it has been embraced by states around the world.

There are refugee camps in Africa where there is a quiet expectation that people will spend their entire lives in, for example the Dadaab camp in Kenya. There are Rohingya refugees in Bangladesh who live in camps and there’s an expectation, or there’s a quiet understanding, that they will never be accepted or embraced by a country and given rights to live in that country freely. So, that’s the kind of global situation of displacement. It is a situation in which the U.S., and many of these powerful states that are today saying we stand with Ukraine, we welcome refugees—these states, like the U.S., Britain, France, are directly responsible for actually producing these refugee populations.

And on one hand we have in this tragic situation an opportunity to entirely transform the ways that refugees are treated. For a number of reasons, good and bad, the Ukraine crisis has revealed to many people, particularly Americans, but people around the world, the realities of war and displacement in ways that were not visible before to a lot of Americans. I wish they had been visible when we’re talking about Syrians and Palestinians and Iraqis. They’re visible in a new way now. And it’s a good thing that there’s a growing awareness and more solidarity and empathy. That’s great. The question is, how do we expand our solidarity and empathy to embrace all of the people who face displacement? That’s the opportunity.

Unfortunately, at the moment we’re seeing the opposite happen by the states of the world. We can start with the neighboring states, like Poland and Hungary. Poland immediately before the Russian invasion of Ukraine was in the news for months because it was barring refugees coming across the border from Belarus. They deployed Polish police to the border, they were putting up fences, and were forcing people, primarily from the Middle East, to wander in the forest and die, freeze to death, starve. And they maintain that regime to this day. Polish activists, who’ve taken great risks to help these migrants, face nine years in prison on the border with Belarus. And the same state, Poland, on the border with Ukraine is welcoming refugees. So, they’ve got a differentiated response. Hungary is the same way. Viktor Orbán recently won re-election. A centerpiece of his campaign and his rule has been xenophobic racism, building a fence on Hungary’s border. And yet he’s said, we welcome Ukrainian refugees. So, there’s this kind of racist, differentiated response to refugees.

Israel has said we’ll take in Ukrainian refugees, we’ll take the Jewish ones. They’re taking some non-Jewish refugees, who are treated quite differently from the Jewish ones. All the while they continue to displace Palestinians into refugeehood. They have a fence on the southern Israeli border directed at Africans, as well as detention centers for Africans. So, that is the response of the world, largely.

And then of course, the United States is playing its part too. And actually, at the moment Ukrainians are arriving at the U.S.-Mexico border. At that border, the U.S. has carried out hundreds of thousands of expulsions of asylum seekers and refugees under something called Title 42, which is this anachronistic public health statute that Stephen Miller and the Trump administration dusted off and said, oh, there’s a pandemic, we can use this to bar refugees and asylum seekers from entering the country on the basis of public health. That is obviously cynical given how the Trump administration denied the existence of a pandemic for so long. So, it’s totally cynical. Biden has maintained it. For two years now, a central demand of migrant justice activists and supporters of refugee rights has been to end Title 42. The U.S. is maintaining it, and yet in the past few weeks has been treating Ukrainian refugees, and some Russian refugees as well, as exceptions to Title 42. So, somehow Haitians, Central Americans, Mexicans, these people all constitute a threat to public health, but Ukrainians don’t. At the moment, the U.S. is actually working with the Mexican government to create a separate track for Ukrainians to seek refugee status in the U.S. They’re housed in different locations in Tijuana upon arrival. And they’re able to bypass the tens of thousands of other people, overwhelmingly people of color, who are waiting at the border to get in. This is disgusting. It is a kind of revelation of the longstanding white supremacy in U.S. border policy.4

It also has to be said that with all of the kind of racist hierarchy and treatment of these different groups of refugees, the U.S. response to the Ukraine crisis is woefully inadequate. The U.S. has said we’ll take in a hundred thousand refugees. There are millions of Ukrainians displaced. So, I think that it’s such a painful illustration of the function of racism, which is on one hand to target and brutalize people of color and black migrants in particular—I mean, this is coming months after Biden summarily deported 12,000 Haitians from the Del Rio crossing in Texas, which totally violates international law. So, on one hand these are the greatest victims of border policy. At the same time, racism lowers the floor for the treatment and the respect of the humanity of all people. It’s not the case that the U.S. is stepping up to the challenge with Ukrainian refugees and leaving others behind. It is kind of reinscribing its racism [but] the whole U.S. refugee system is severely out of step and such an injustice given the level of displacement in the world today. There are some 32 million people who the UN counts as refugees and the U.S. arbitrary cap for refugees is 125,000. It’s pathetic. So, the challenge is for us to entirely transform the whole refugee system, obviously with anti-racism at the center of that transformation. And that is about really speaking to the need that exists for displaced people in the world.

Notes

1. “Why Binary Thinking on Russia’s Invasion Is a Losing Strategy,” YES!, March 7, 2022.

2. “U.S. Militarism Is a Cause of Tension in Eastern Europe, Not a Solution,” In These Times, February 8, 2022.

3. “Sanctions May Sound ‘Nonviolent,’ But They Quietly Hurt the Most Vulnerable,” Truthout, March 6, 2022.

4. Khury Petersen-Smith and Azadeh Shahshahani, “Time to End the West’s Xenophobic Double Standard on Refugees,” The Nation, May 18, 2022.

Leave a Reply