As the climate crisis worsens, struggles against fossil fuel pipelines have united such unlikely forces as young climate activists, white-settler land owners, and Indigenous nations. These fights have started to center the issue of Indigenous land rights, both on the ground and in the courts.

As the climate crisis worsens, struggles against fossil fuel pipelines have united such unlikely forces as young climate activists, white-settler land owners, and Indigenous nations. These fights have started to center the issue of Indigenous land rights, both on the ground and in the courts.

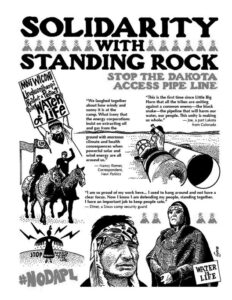

Land rights have been a focus of Indigenous struggles since the first Europeans came to the continent of Turtle Island, but the radicalization that now puts settler colonialism itself on trial has its origins in the Standing Rock encampment in 2016. This article gives an overview, in part from the author’s firsthand experience, of the roots of the struggle against the Dakota Access Pipeline (DAPL), what the encampment was like, the violence of the state’s response, and the lasting impact of these events.

[The inset italicized sections below are from the author’s personal journal.]

As we drove through heavy thunderstorms, we felt the nerves, excitement, and sacredness of where we were going. This was a historic time of resistance, but it’s not the first time this has happened on the northern Great Plains.

Once we hit North Dakota, we saw that the signs for state roads were labeled with an Indigenous head—a reminder of not-so-thinly veiled racism. On roads with large numbers, they just stretch the Indigenous head to fit.

As night fell and we drove on, it was possible to imagine the time before the United States invaded Lakota country. Sitting Bull and Crazy Horse would be proud of what their relatives are doing today.

We turned onto a road with a handmade sign pointing us toward the Sacred Stone Camp—the area on the Standing Rock Indian Reservation started back in April 2016 to protest the pipeline. Signs say, “No alcohol, no drugs, no guns.” Someone else added another slogan at the bottom: “No DAPL.”

We were greeted with excitement, like everyone is who comes to offer solidarity and support. We dropped off donations of food and camping supplies and got the lay of the land.

We were told it was about a 15-minute walk to the Oceti Sakowin camp. Oceti Sakowin is the Seven Council Fires, or the Lakota, Nakota, and Dakota people (Sioux). This larger camp was not on the reservation, but on land stolen by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, which made it more vulnerable to forces of the federal government coming in and kicking them out.

We can see hundreds of flags whipping violently in the strong wind. Taking a closer look at these flags, we see Indigenous nations represented from all over Turtle Island and the world—flags representing Leonard Peltier, Omaha Nation of Nebraska, Cherokee Nation, Oglala Lakota, Ojibwe Nation, Hiawatha Nation, Turtle Mountain Band of Chippewa, Forest County Potawatomi, the American Indian Movement. There were also flags from Palestine, Iran, and the Sami people of northern Europe and an LGBT pride flag.

This is the first time in recent history that this number of nations have come together in a united struggle—defying the long history of divide and conquer on the part of colonizing governments.1

Such was the view before me upon entering the Oceti Sakowin encampment at Standing Rock. The struggle attracted the attention of millions from around the world. The encampment lasted nearly a year, from April 2016 to February 2017, but the struggle against the DAPL has been ongoing ever since Energy Transfer Partners, a Canadian fossil fuel company, began building a $3.8 billion project in 2014.

DAPL stretches 1,172 miles from the Bakken oil fields in North Dakota through South Dakota and Iowa, before ending in Illinois.2 It carries a daily load of 570,000 barrels of oil, extracted through hydraulic fracturing, across 209 rivers, creeks, and tributaries. Activists, dubbed water protectors at Standing Rock, forced the Obama administration to stop the pipeline in 2016, until Trump reversed the decision during his first days in office.3 The pipeline permits are still being challenged in the courts, and President Biden is facing renewed pressure to shut down DAPL, having shut down the Keystone XL pipeline in 2022 following a catastrophic oil spill.

In the fight against DAPL, the environmental and Indigenous movements united under the slogan Mni Wiconi, which is Lakota for “water is life,” to emphasize that the demand for clean water is not just for Indigenous people but for everyone down river. But the forces rallying at Standing Rock also stood for treaty rights and Indigenous sovereignty, and against settler colonialism. An increasingly radical climate justice movement had started to critique the core of the ecological crisis: capitalism and colonialism.

Why Standing Rock? Why Now?

Referring to the invasion by the United States of the Lakota country, Hunkpapa Lakota medicine man Sitting Bull once stated,

We have now to deal with another race—small and feeble when our fathers first met them, but now great and overbearing. Strangely enough, they have a mind to till the soil, and the love of possession is a disease with them. These people have made many rules that the rich may break but the poor may not. They take their tithes from the poor and weak to support the rich and those who rule.4

His assessment still stands: DAPL and other pipelines extend the dispossession, heedless of the consequences for the earth or the people whose land is invaded. The history of the United States is one of extraction involving the attempted and sometimes successful removal of Indigenous nations from their homelands. Indigenous people have resisted, and in some cases they have been successful in preventing further environmental destruction.

So why was Standing Rock different from other times? How did it become the largest Indigenous gathering in the United States since the occupation of Wounded Knee in 1973? Before we answer those questions, we must take a step back and look at the role land has played in the U.S. colonial project.

The United States made more than 300 treaties with Indigenous nations and has continued to break every one of them in its thirst for more profits by the fossil fuel industry. As Roxanne Dunbar-Ortiz puts it in An Indigenous Peoples’ History of the United States,

Everything in U.S. history is about the land. Who oversaw and cultivated it, fished its waters, maintained its wildlife; who invaded and stole it; how it became a commodity (“real estate”) broken into pieces, to be bought and sold on the market.5

Along with land theft, the United States projects myths around the taming of the wilderness, implying that Turtle Island (North America) was empty of people when European settlers arrived. In reality, millions of people were living on Turtle Island, the majority of them farmers who lived sustainably with their nonhuman relatives.

In his book Red Skin, White Masks: Rejecting the Colonial Politics of Recognition, Glen Coulthard, a citizen of the Yellowknives Dene, describes Marx’s theory of primitive or primary accumulation as the process where capital displaces the Indigenous population and privatizes the land to make it a commodity. This is what Coulthard calls a “violent transformation of noncapitalist forms of life into capitalist ones.”6

That totalizing power of capital in the North American context required settlers and settler colonialism to overturn Indigenous modes of production and relationship to the land and to supplant them with capitalist markets. Previously, most Indigenous nations on Turtle Island did not have “private property,” and land was held in common. Along with private property, colonialism brought individualism to drive the commodification of land. In contrast, Indigenous nations relied on interdependence and what Winona LaDuke calls co-evolution with their environment and surroundings. From the Indigenous perspective, colonialism transformed abundance to scarcity.

Capitalism and settler colonialism entail more than simply taking land. they also separate people from the whole living world they inhabit — animals and plants as well as land. The attempted removal of Indigenous people was intentional because their knowledge and connection to their homeland threatened the capitalist process of commodifying the entire world to exploit it for profit.

The struggle at Standing Rock challenged this dynamic. It came on the heels of a new push for Indigenous liberation on Turtle Island, starting with the Idle No More movement in 2013 in Canada and continuing through to the struggle against the Keystone XL pipeline that lasted throughout the Obama administration. Within this same era, we saw the rise of the Occupy movement in 2011 and the Black Lives Matter movement in 2013. Standing Rock became a moment and a specific struggle that drove people to question the nature of the U.S. colonial project.

Leading to the Oceti Sakowin Encampment

The encampment against DAPL started in the wake of the proposal that the pipeline be routed north of Bismark, the capital of North Dakota.7 Residents of the city, which is 90 percent white, opposed its construction, and the pipeline company quickly responded by relocating the route to right outside of the Standing Rock Indian Reservation. The not-so-thinly veiled racism was evident from the outset.

The Standing Rock Sioux Tribe (SRST), also known as the Hunkpapa Lakota Nation, led the resistance.8 Before the encampment developed, the SRST filed a lawsuit against the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, which had quietly approved the pipeline without the consultation with the tribe that is required in treaty agreements. The SRST said the route of the pipeline—through the Missouri River and Lake Oahe—would disturb tribal burial grounds and affect the nation’s drinking water. “The Corps puts our water and the lives and livelihoods of many in jeopardy,” Standing Rock Sioux Chair Dave Archambault II said. “We have laws that require federal agencies to consider environmental risks and protection of Indian historic and sacred sites. But the Army Corps has ignored all those laws and fast-tracked this massive project just to meet the pipeline’s aggressive construction schedule.”9

In April 2016, protesters set up the first encampment, known as the Sacred Stone Spiritual Camp, at the confluence of the Cannonball and Missouri Rivers, which form the borders of the reservation. This camp, which was located on the reservation, quickly grew to capacity, and the second and the most well-known camp, Oceti Sakowin, was built on land that was stolen by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, which left water protectors more vulnerable to state violence. The camps would attract thousands of water protectors, both Native and non-Native, over the coming months. Jon Eagle Sr., SRST’s tribal historic preservation officer, explained the historic and cultural significance of the site:

The land between the Cannonball River and the Heart River is sacred. It’s a historic place of commerce, where enemy tribes camped peacefully within sight of each other because of the reverence they had for this place. In the area are sacred stones where our ancestors went to pray for good direction, strength, and protection for the coming year. Those stones are still there, and our people still go there today.10

In 1851 and 1868, the Oceti Sakowin signed the Fort Laramie Treaty with the U.S. government, creating the Great Sioux reservation, which included all of South Dakota west of the Missouri River. The 1868 treaty stated that “no white person or persons shall be permitted to settle upon or occupy any portion of the [territory]; or without the consent of the Indians, first had and obtained, to pass through the same.”11 The treaty also protected hunting rights in the surrounding area, including where the pipeline was set to go through. The United States unilaterally ended treaty-making in 1871 and in 1877 officially stole the sacred Black Hills, which the Lakota knew as He Sapa. Though the United States broke its treaties with the Lakota (and every other Indigenous nation), the agreements have been the legal framework for Indian law since the 1970s.12

It is with this framework that we must understand the events at Standing Rock: It was a struggle for self-determination and treaty rights. It was also a continuation of the successful fight waged by Native activists and environmentalists against the Keystone XL pipeline.

The SRST called on the Obama administration to halt the pipeline. Obama’s relationship with the SRST began after his June 2014 visit to their reservation, making him only the fourth sitting president to make an official visit to an Indian reservation.13 But Obama and 2016 Democratic presidential nominee Hillary Clinton were silent on the issue of the DAPL. The Democratic Party continued to promote an “all of the above” energy strategy that includes fracking and the new oil fields in North Dakota.

Life at the Oceti Sakowin Encampment

To continue from my account of entering the encampment:

Within the Oceti Sakowin camp is the Red Warrior camp, which has been the base of the most vibrant and militant direct-action protests.

As we walked to the Oceti Sakowin camp, our way was partially blocked off by a broken-down car that has been spray-painted, “No DAPL, Save the Water” and “Protectors.” This last slogan is a reference to what Native leaders of the struggle have been saying: “We are not protesters, we are protectors.”

We come up around a bend to see the confluence of the Cannonball River and the Missouri River. There are hundreds of tents and teepees—which immediately gives me chills at the historic moment I’m a part of.

We went to what was called “Facebook Hill,” the highest point of the camp and the only place to get somewhat decent cell phone reception, to check in at the press tent. There are solar stations to charge phones and laptops.

From this vantage point, you can see the entire camp, sprawling toward the river and beyond the small hills. There are over a thousand small tents mixed with teepees, and it’s impossible not to think about generations of Lakota, going back hundreds of years, who pitched camps just like these.14

The struggle at Standing Rock played out in the media with a series of court cases and high-profile police conflicts, but day-to-day life in the camp was the fuel that kept the fight going. The encampment gave us a glimpse of what a world based on kinship and good relations with mother earth looks like, by contrast with destruction and oppression inherent in a system that values commodities over human lives. It was led by (as Indigenous scholar Kim TallBear said) “badass Indigenous women.”15 As Charlie Aleck reflected in an International Socialist Review article,

At its peak, 15,000-20,000 people lived and worked at the Oceti Sakowin and Sacred Stone camps. You could get lost from one side to the other in a day as new tents were put up, old tents collapsed, and new pathways worn in. The usual landmarks were “the green tent with such and such flag” or “the beige van next to the porta potties.” If you had been there more than a few days, you could recall the smaller camps by name—Lower Bruhle, Red Warrior, Two-Spirit, the International Youth Council, and so on. You might even know there was a second sacred fire at the Headsmen camp.

Each day starts with a water ceremony at 6:00 a.m. Each meeting begins with a prayer. You take these opportunities throughout the day to remember that you and the people standing next to you are all fighting for a sacred land and water, and you speak of it in the language of the Oceti Sakowin (the original name of the Sioux Nation). You pray under the banner “Mni Wiconi,” water is life, because the Oceti Sakowin have used this place for ceremony since time immemorial, and downstream are several million people who depend on this waterway for their drinking water. The fight is very literally life or death.

The prayer gives you a break in the hustle and bustle to ground yourself again and offers you the courage to fight another day. To survive the coming cold, you must be able to depend on your neighbor and they on you, until the pipeline, this “Black Snake” of Oceti Sakowin prophecies, is dead in its tracks. At the end of Lakota prayers, they say, “Mitakuye Oyasin,” meaning, “We are all related.” It is solidarity in action borne of necessity.16

The ethic of Mitakuye Oyasin was central to the activity in the camp, which included action training, food distribution, media, legal support by the National Lawyers Guild, two-spirit support, and much more. Everything was free for everyone and genuinely embodied what Karl Marx meant in writing, “From each according to his ability, to each according to his needs.”

State Violence Against Water Protectors

Not surprisingly, the state had zero tolerance for this protest. The peaceful encampment quickly faced violence from the police, private security (including the counterinsurgent private contractor called TigerSwan), and National Guard forces from all over the country. Morton County Sheriff Kyle Kirchmeier made absurd claims during the summer of 2016 that the protesters were about to physically destroy the pipeline. “They were preparing to throw pipe bombs at our line, M80s, fireworks, things of that nature to disrupt us,” he said.17 These claims were a pretext for law enforcement to come out and harass water protectors, including setting up checkpoints near the encampment.

Following Kirchmeier’s claims, Energy Transfer Dakota Access LLC filed lawsuits against protesters at the site, including SRST Chair Dave Archambault. The company claimed protesters “have created and will continue to create a risk of bodily injury and harm to Dakota Access employees and contractors, as well as to law enforcement personnel and other individuals at the construction site.”18

Police attacks on water protectors came after a federal appeals court lifted a temporary injunction against construction on October 9, opening the way for Energy Transfer Partners to resume construction. On October 22-23 nearly 130 water protectors were arrested and charged with crimes including aggravated assault, participating in a riot, and resisting arrest.19

On October 27, police unleashed a wave of brutality on water protectors in Standing Rock, who had recently moved their encampment directly in the path of DAPL construction. Over 300 highly militarized police with armored vehicles and riot gear joined with 80 military personnel and 150 DAPL workers to unleash rubber bullets and bean bag rounds on the water protectors. More than 40 people suffered injuries, including welts and broken bones. Some 141 people were arrested.20

Tara Houska, then national campaigns director for the Native activist group Honor the Earth, described the brutality on Democracy Now!:

There were police walking around everywhere with assault rifles. Directly across from us, there was actually a policeman holding his rifle trained on us, directly on us. Bean bag rifle assault—bean bag nonlethal weapons were also aimed at us. Every time we put our hands up, they’d put them down. As soon as our hands came down, they would aim back at us. Police officers were smiling at us as they were doing these things. There were police officers filming this, laughing, as they—as human beings were being attacked, being maced. I mean, it was a nightmarish scene. And it should be a shame to the federal government, it should be a shame to the American people, that this is happening within U.S. borders to Indigenous people and to our allies, to all people that are trying to protect water. Yesterday was a really shameful moment for this country and where we stand.21

Others on the ground recalled the violence. Lauren Howland, a 21-year-old member of the Youth Council, described her experience outside the Morton County jail in Mandan, North Dakota, in a video that appeared on Facebook:

They flanked us, they corralled us, and then they started taking us out … They gave us two options—either get arrested or leave peacefully, and we were on our way out peacefully, and they started macing us … and pushing us with their batons. They surrounded us.22

Then came the famous images of the Morton County police shooting cannons of water and rubber bullets on the encampment in below-freezing conditions on November 20, 2016.23 The violence of the police continued until the final days of the encampment after Donald Trump came into office.

Although the physical attacks ended, state violence continued through lengthy court cases and imprisonment of water protectors such as Red Fawn24 and Marcus Mitchell.25 Within Indigenous communities this is nothing new; after all, Sitting Bull, Crazy Horse, and countless others were imprisoned resisting U.S. settler colonialism in the 1800s, and the FBI infamously did the same to the American Indian Movement following the occupation of Wounded Knee in 1973. Standing Rock is merely one of the latest iterations of state-sanctioned violence against Indigenous people.

Solidarity Against Settler Colonialism

Despite the extreme violence, millions were inspired to join the struggle at Standing Rock, including billions of people who “checked in” on Facebook in order to try and confuse law enforcement who were using social media to find water protectors.26 Indigenous people led the way, creating the opportunity to build a multiracial movement against climate change.

One resounding message from Indigenous activists has been the power of solidarity. During the fight against the Keystone XL pipeline, for example, Natives and non-Natives formed the Cowboy-Indian Alliance.27 Similar coalitions were forged in the Standing Rock struggle.

Crow Creek Sioux Tribal Chair Brandon Sazue explained in a Facebook statement why he and his tribe were offering support:

We will stand with you, my relatives. Whether we are Native, white, African American, etc. Our water is our most precious resource along with our children. We must all stand together in this most urgent of times. This is not about race, but about the human race! What we do today will make a difference tomorrow! If there was ever a time to stand united, that time is now!28

This sentiment was widespread in Indian Country. Oglala Sioux Tribal President John Yellow Bird Steele sent supplies and buses of people from the Pine Ridge Indian Reservation to Cannonball to support the protesters.

The environmental implications of what was happening helped the movement gain traction among non-Natives, but from an Indigenous perspective, sovereignty was at the core of this fight. The immediate connection between environmental justice and Indigenous sovereignty enabled many non-Native activists to see Indigenous land rights as a lynchpin to the fight for climate justice and, ultimately, to question the nature of the U.S. colonial project.

One of the more powerful moments of solidarity came in December 2016, when more than two thousand veterans gathered to offer defense amid worrisome signs that law enforcement intended to destroy the encampment. It would have been a public relations nightmare for the pipeline and the authorities if police forces turned their weapons on veterans. These veterans did not just come to help, but also to apologize for the military’s role in the attempted ethnic cleansing of Indigenous peoples. Wesley Clark Jr. led the group and spoke passionately at a ceremony, saying,

Many of us, me particularly, are from the units that have hurt you over the many years. We came. We fought you. We took your land. We signed treaties that we broke. We stole minerals from your sacred hills. We blasted the faces of our presidents onto your sacred mountain. When we took still more land and then we took your children and then we tried to make your language and we tried to eliminate your language that God gave you, and the Creator gave you. We didn’t respect you, we polluted your Earth, we’ve hurt you in so many ways but we’ve come to say that we are sorry. We are at your service and we beg for your forgiveness.29

The emotion was palpable. It was a turning point for so many and created even greater determination to fight back.

Lasting Impact: The Struggle Continues

The fight against DAPL shifted after Donald Trump was inaugurated, with activists split between continuing the encampments and pursuing a legal path forward in the courts. On February 1, 2017, the final encampment was shut down by law enforcement after they carried out 74 arrests of water protectors establishing a new camp.30

Though the pipeline was completed following Trump’s green light, the permits continued to face legal challenges. As recently as July 2020,31 courts ordered the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers to conduct an environmental impact study, only to be overturned by an appeals court the following month.32 Then in early 2021, a judge ruled that the pipeline was operating without the necessary federal permit and needed to undergo an environmental impact review. The courts are hearing evidence from both sides to determine whether the pipeline should be shut down while the review is conducted.33

Since President Biden shut down the Keystone XL pipeline, pressure to shut down DAPL has increased. Celebrities, along with key environmental organizations such as the Sunrise Movement, Indigenous Environmental Network, 350.org, Zero Hour, and the Sierra Club, signed a letter urging President Biden and Vice President Harris to shut down DAPL.34 The letter came on the heels of Lakota youth running a 93-mile relay across Standing Rock to the site of the former Oceti Sakowin encampment, demanding that DAPL be shut down.35

Even as the struggle continues and changes, Standing Rock’s radicalizing influence persists. It was Representative Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez’s experience at Standing Rock that inspired her to introduce the Green New Deal. The struggle inspired countless other protests against pipelines throughout Turtle Island, from Wet’suwet’en territory in Northern British Columbia to Line 3 in Northern Minnesota.

A whole new generation of activists has learned the long history of the United States continually breaking treaties with Indigenous nations: how the United States stomps over their self-determination any time the government or corporations need access to Native lands to extract energy and raw materials. As our planet burns and our ecosystems are destroyed for profit and capitalist expansion, it is vital that our solutions to the crisis center Indigenous nations’ historic right to their lands, resources, and sacred sites.

This piece would not have been possible without two of my close Indigenous comrades, Ragina Johnson and Charlie Aleck. I have collaborated and worked with them over the years. All three of us went to Standing Rock together and collaborated on our journals.

notes

1. Parts of this journal were originally published in collaboration with Ragina Johnson and Charlie Aleck in Socialist Worker. “The Road That Brought Us to Standing Rock”, Socialist Worker, Oct. 3, 2016.

2. Dakota Access Pipeline, “Moving America’s Energy: The Dakota Access Pipeline”.

3. Robinson Meyer, “Trump’s Dakota Access Pipeline Memo: What We Know Right Now,” The Atlantic, Jan. 24, 2017.

5. Roxanne Dunbar-Ortiz, An Indigenous Peoples’ History of the United States (Beacon Press, 2014).

6. Glen Coulthard, Red Skin, White Masks: Rejecting the Colonial Politics of Recognition (University of Minnesota Press, 2014), 7.

7. United States Census Bureau, “Bismarck city, North Dakota.”

9. EarthJustice, “Standing Rock Sioux Tribe Takes Action to Protect Culture and Environment from Massive Crude Oil Pipeline,” July, 27, 2016.

10. Logan Glitterbomb, “Indigenous Property Rights and the Dakota Access Pipeline,” Counter Punch, Aug. 30, 2016.

11. Fort Laramie Treaty of 1868.

12. “SECTION 3: THE TREATIES OF FORT LARAMIE, 1851 & 1868,” North Dakota.

13. Brian Ward, “The Ongoing Betrayal of Native Nations,” Socialist Worker, Aug. 6, 2014.

14.Ryan G., Ragina Johnson, Chance Lunning, Rene Rougeau, Cole Sutton and Brian Ward. ”The View at Standing Rock,” Socialist Worker, Oct. 4, 2016.

15. Nick Estes and Jaskiran Dhillon, eds., Standing with Standing Rock: Voices from the #NoDAPL Movement (University of Minnesota Press, 2019), 13.

16. Charlie Aleck (writing as Sara Rougeau), “We Have Always Been Here: Reflections on the Standing Rock Protest,” International Socialist Review, Issue #104.

17. Kris Maher and Alison Sider, “Clashes Halt Work on North Dakota Pipeline,” Wall Street Journal, Aug. 18, 2016.

18. James MacPherson, “Pipeline Owners Sue Protesters,” Milwaukee Journal Sentinel, Aug. 15, 2016.

19. Charlie Aleck (writing as Sara Rougeau), “Mass Arrest at Standing Rock,” Socialist Worker, Oct. 27, 2016.

20. Common Dreams, “#NoDAPL: Native American Leaders Vow to Stay All Winter, File Lawsuit Against Police,” Common Dreams, Oct. 29, 2016.

21. “A Shameful Moment for This Country: Report Back on Militarized Police Raid of DAPL Resistance Camp,” Democracy Now!, Oct. 28, 2016.

22. Sacred Stone Camp, “A statement from a water protector,” Facebook, Oct. 22, 2016.

23. Alan Taylor, “Water Cannons and Tear Gas Used Against Dakota Access Pipeline Protesters,” The Atlantic, Nov. 21, 2016.

24. Will Parrish, “Standing Rock Activist Accused of Firing Gun Registered to FBI Informant Is Sentenced to Nearly Five Years in Prison,” The Intercept, July 13, 2018.

25. Will Parrish, “Standing Rock activist faces prison after officer shot him in the face,” The Guardian, Oct. 4, 2018.

26. Brett Molina, “Why People Are Checking in to Standing Rock on Facebook,” USA Today, Oct. 31, 2016.

27. Brian Ward, “Cowboy-Indian Solidarity Challenges the Keystone XL,” System Change Not Climate Change, March 18, 2014.

28. Reservation News, “Support Grows Despite Arrests at Dakota Access Pipeline Protest,” Kumeyaay.

29. Jenna Amatulli, “Forgiveness Ceremony Unites Veterans and Natives at Standing Rock Casino,” Huffington Post, Dec. 5, 2016.

30. Charlie Aleck (writing as Rene Rougeau), Ragina Johnson, and Brian Ward, “The Challenge at Standing Rock,” Socialist Worker, Feb. 7, 2017.

31. Helen H. Richardson, “Court Orders Shutdown and Removal of Oil from the Dakota Access Pipeline,” Truthout, July 6, 2020.

32. Reuters, “U.S. court allows Dakota Access oil pipeline to stay open, but permit status unclear,” Aug. 5, 2020.

33. Nina Lakhani, “Celebrities Called on Biden and Harris to Shut Down Dakota Access Pipeline,” The Guardian, Feb. 9, 2021.

34. “Dear President Biden and Vice President Harris: Shut down DAPL,” Feb. 8, 2021.

35. “Shutdown DAPL Run.”

Leave a Reply