Arthur Henry Young (1866-1943), known to the world as Art, was arguably the most widely recognized and beloved cartoonist in the history of American radicalism. A working cartoonist for sixty years, Art Young drew thousands of simple black-line drawings with biting captions that appeared in big-city newspapers, liberal magazines, and, most importantly, in the socialist, labor, and radical press of the early twentieth century.

Arthur Henry Young (1866-1943), known to the world as Art, was arguably the most widely recognized and beloved cartoonist in the history of American radicalism. A working cartoonist for sixty years, Art Young drew thousands of simple black-line drawings with biting captions that appeared in big-city newspapers, liberal magazines, and, most importantly, in the socialist, labor, and radical press of the early twentieth century.

Starting in Wisconsin shortly after the end of the Civil War and ending in the midst of World War II, Art Young’s life, art, and activism span the Age of Monopoly and the Great Depression. At the peak of his influence, Art’s clear yet stylish cartoons helped give a visual design and humo rous edge to a wave of anti-capitalist social movements—socialist, anarchist, communist, Wobbly, feminist, labor, and Black radical—organized in opposition to the unchecked power of monopoly capitalism, Wall Street finance, government surveillance, and racist nationalism.

For these reasons, after the passage of a century or more, Art Young’s cartoons strike us as surprisingly relevant to our current era of inequality, ecological crisis, police violence, and war.

Formally educated in art schools in Chicago and Paris, Young chose graphic and cartoon art from an early age as his “road to recognition.” Art recognized that painting was singular and slow, whereas, in his words, “a cartoon could be reproduced by simple mechanical process and easily made accessible to hundreds of thousands. I wanted a large audience.” Young published his first cartoon in Judge magazine in 1883 and thereafter learned his craft in the editorial offices of Chicago and New York’s biggest papers, working for a time under Thomas Nast, the most important American cartoonist of the nineteenth century.

In both art and activism, Young’s career stretched between his jailhouse portraits of the Haymarket Anarchists, drawn days before their execution in 1887, and a Fourth of July picnic in 1918 at the home of Eugene V. Debs, the Socialist Party presidential candidate, just a few days before Debs’ arrest for an anti-war speech. Somewhere in between, Young converted to socialism and turned against the capitalist system. Art even ran for public office in New York City on the Socialist Party ticket. “I have always felt,” he wrote in 1928, “that there is more power in my talent than in the mind of the statesman.”

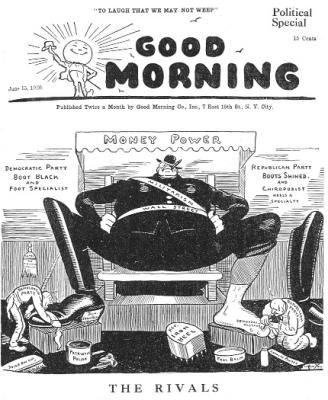

Young published his best cartoons in the early twentieth century alongside John Sloan, Maurice Becker, William Gropper, Stuart Davis, and George Bellows in small radical magazines like The Masses, The Liberator, and his own brilliant, if short lived, journal Good Morning. Art stood at the center of a community of radical artists working in the heart of Greenwich Village’s modernist bohemia.

Nearly unique in the history of political cartooning and the American left, Art Young’s talent as a humorist enabled him to reach deep into the mainstream. Art drew cartoons for the liberal Metropolitan and The Nation magazines, and he sold sentimental and ironic drawings to family magazines like Life, Puck, and the Saturday Evening Post. He once explained that he could draw his anti-capitalist cartoons for middle class readers as long as he labeled the villain “greed” rather than “capitalism.” But he made these choices so that he could afford to express himself fully in the pages of the radical press.

“Radical publications paid little,” wrote Young of The Masses, “generally nothing in real money, for contributions, but paid a good deal in that coin of consolation, that comfort to the mind when it is relieved of pent-up grievances against social conventions and the tyranny of wealth.”

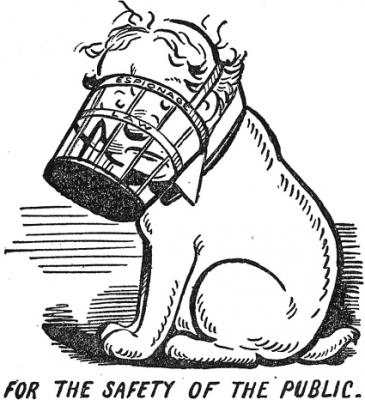

For his troubles, Young was censored by the Postal Service, threatened with libel suits by the Associated Press, and, in 1918, he, Max Eastman, Jack Reed, and the rest of the editors of The Masses faced two federal sedition and criminal conspiracy trials where they narrowly escaped life sentences. In the defeated years of the 1920s, he covered politics and presidential campaigns, and in the resurgent 1930s he drew for the Daily Worker and New Masses, published two autobiographies, and created his greatest work, a vision of the inferno in which dead capitalists have colonized hell itself.

Almost exclusively drawn in pen and ink, Art Young’s cartoons are notable for combining formal simplicity with conceptual complexity. His best cartoons depict vast social conflicts on a level of abstraction—plutocracy versus democracy—that made his work instantly accessible, effortlessly humorous, and deceptively didactic. “I was much more interested always in drawing cartoons which would strike at a vulnerable point in the armor of the common enemy,” wrote Young, “than in battling over the fine points of tactics.”

Material social forces are abstracted into individual cartoon characters, his single panel images forming broad social melodramas featuring bloated and arrogant plutocrats, the puppet politician, the bull-necked police and jackbooted militarist, the harlot “capitalist press,” the dignified yet dispossessed poor, and the occasional heroic socialist. By this method of abstraction, Art’s cartoons frequently sought to represent or reveal the nature of capitalism as a whole, cartooning the social totality in a single, simple image.

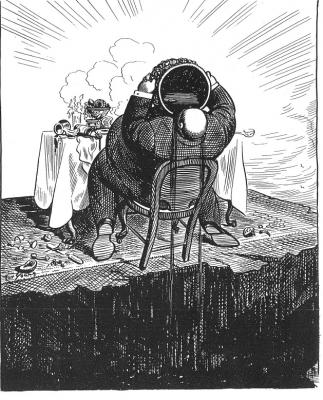

We can see Art’s gift for abstraction in a 1920 cartoon simply entitled “Capitalism.” Young’s image personifies a global economic system with billions of working human and industrial parts as a fat, bald white man, tipping back in his chair over a blackened chasm. He is an intoxicated glutton blindly eating himself to death—that much is obvious. But the image also dramatizes the fiction of corporate personhood (established by the Supreme Court in 1886), transforming the abstract logic of accumulation into a personal appetite blind to all that it endangers, including to the grotesque capitalist himself. Dangling unaware on the edge of a cliff, the capitalist world is dangerously out of balance. “‘Après moi, le déluge!’ is the watchword of every capitalist,” writes Karl Marx in one of many possible sources for this image.

Perhaps this cartoon telegraphs a vision of ecological disaster for our own time. The steam billowing off the heaping platters builds into storm clouds, while the radiating heat of the unseen sun adds its energy to the inevitable tipping point. But what happens when the chair tips over and the capitalist falls off the cliff? What happens to the rest of us? The answer was as true for Marx as it was for Young and as it remains for us now: Without socialism we will all drown.

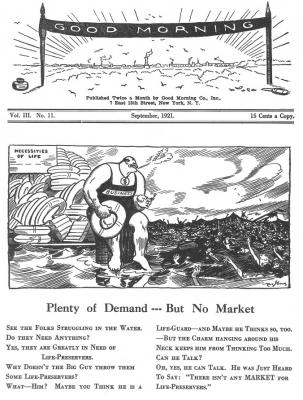

For more on this theme of capitalism personified in a drowning world, consider another cartoon from the early 1920s. At the center of the page sits a pompous man labeled ‘‘business” occupying an ocean pier, dressed in the height of Newport Beach swim fashion, with his toes leisurely playing in the water. A mountain of life preservers looms uselessly behind him, while countless men, women, and children struggle in the rising waters. The caption simply states what any good economist recognizes as an iron law: “Plenty of Demand — But No Market.”

Both immediate and sophisticated in its critique, Young’s cartoon helps visualize Marx’s theory of value in two ways. First, in taking the laws of supply and demand at face value, Young depicts the capitalist system as a grotesque catastrophe in which plentiful (overproduced even) resources are incapable of being matched up with overwhelming need. That which cannot be sold (without exchange-value), has no value at all in a capitalist society. So waste and privation pile up side by side.

Secondly, Young’s drama explicitly humanizes the economic system by insisting upon the moral encounter behind the supposedly impersonal laws of exchange. In Young’s image, the “laws of supply and demand” are revealed to be the result of real ethical choices in which profits (to the capitalist at least) are more valuable than people. Economics, mocked in both image and text, merely offers a pseudo-scientific justification for ruling-class moral blindness. The socialist solution of organizing “use values” (and kicking the bully off the pier) seems the only option for our collective survival.

If Art Young’s plutocrats reveal a self-destructive logic, his vision of the state is one in which plutocracy has defeated democracy. In this cover of Good Morning from the presidential election of 1920, an enthroned and “manspreading” sovereign serves under the banner of the “Money Power” while scraping minions from the two political parties polish his jackboots, pedicure his toes, and replace his repressive “Iron Heels.” Young’s black-uniform-wearing agent of repression is labeled “Wall Street” and “Militarism” for the counter-subversive coalition that pushed the United States into World War I and the Red Scare. In short, this cartoon offers a unique vision of an authentic American fascism at the start of the 1920s.

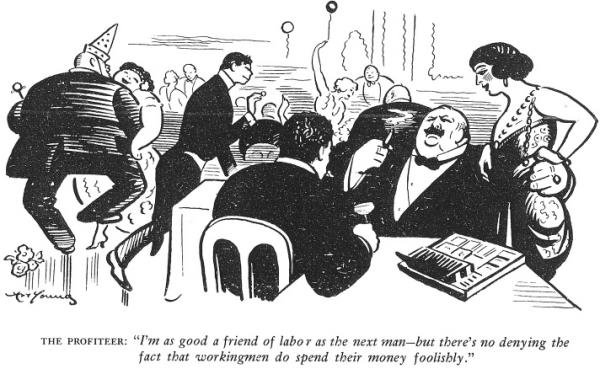

If one of Art’s gifts was the totalizing allegory, he also had a talent for capturing the political stakes in simple human encounters. These far more intimate cartoons—socialist morality plays—enabled Young to satirize the platitudes and conventions of social interaction. In one example, seen below a fattened “Profiteer,” cigar in one hand and a fashionable young lady in the other, professes his concerns (or thinly disguised disgust) for the moral choices that poor workers make with their scant earnings. He seems like one of those men who pay his employees lowered wages out of concern for their moral well-being. Of course, the Profiteer spends his boundless money on parties and liquor, frivolous merriment that seems to leave him feeling judgmental but seemingly no happier. “Apres moi, le deluge” indeed.

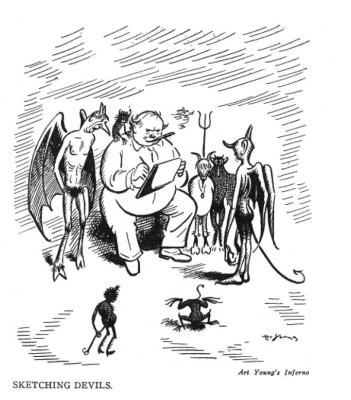

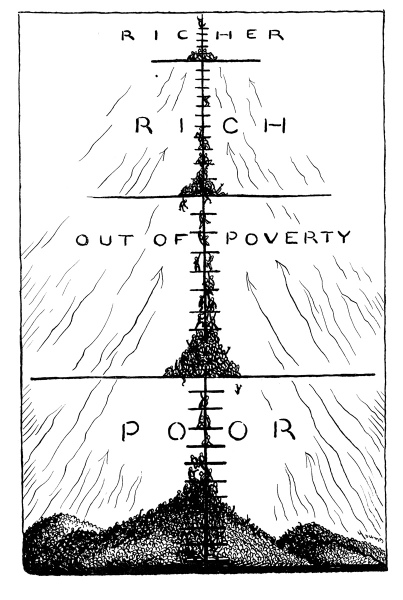

Art’s last major work, Art Young’s Inferno, published in 1934, was his third book-length updating of Gustave Doré’s famous engravings of Dante’s Inferno. In his darker moods, Young believed that capitalism made a hell of the earth, the struggle to climb the economic ladder being the equivalent of struggling out of the pit itself.

But with so many of their class condemned to hell, Art imagined the capitalists leading a hostile takeover, deposing old man Satan, installing their own CEO, and transforming the inferno into the last refuge of the free market. “Capitalism on earth is doomed,” declares a damned soul to Young along his travels. “It spread over the world for hundreds of years, now Hell is the only available place left – the last outpost, and believe me, we are going to make a good job of it – no fool notions. They say, ‘We live and learn,’ but we had to die to learn.”

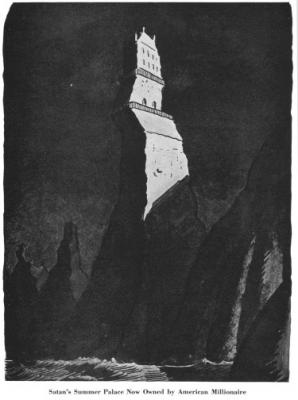

Of course, capitalism seems to naturally thrive in hell, triggering a wave of privatization, monopolization, and gentrification, upsetting many of the older natives of the underworld. Thanks to the Hell Water Power Co., the single most powerful entity in hell, all the parks charge admission and cool breezes cost a dollar, bathrooms are rare and expensive, and highways charge a toll each and every mile. Hospitals only treat sinners who can pay (“the fraternal racket of gouging the sick”). Real estate speculation has grown so fevered that caves are rented for a fortune and an American millionaire just set a record by buying Satan’s old summer home. Sounds like San Francisco in 2015. In short, the entire book is a lost masterpiece of anti-capitalist humor and a priceless assault on the fundamentalist logic of free-market capitalism that may be more relevant now than it was 80 years ago.

Comedian and radical teacher, popular artist, and a revolutionary critic, Art Young’s time has come again, and we need him now more than ever.

[…] Another website, looks at the more radical art movements of the 1920s. In this piece the artist uses abstraction to personify the global economic system as a fat, powerful man who abuses his power through having the smaller and weaker classes quite literally shine his shoes. This is likely a nod to the old fashioned services that poorer people would provide to the richer classes, connoting that this kind of use of power is also present in global economics and money handling. In these kinds of cartoons, ruling classes and powerful figures are often personified as greedy animals, provoking thoughts of glutton and over indulgence as a result of all the surplus money. Alternatively, the poorer working classes are depicted as small and scrawny, very reminiscent of their pockets and bank accounts. […]