The most radical and militant union in American history was the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW), colloquially known as the Wobblies. Its active years were from 1905 to 1919, or at best until mid-1920 when it led its last major struggles—a maritime workers strike in California and a miners strike in Colorado. Fierce government repression during and after World War I, along with vigilante violence and internal divisions, dealt the IWW blows from which it never recovered. The mass industrial union movement during the New Deal passed it by. Yet, the IWW continues to exist on a small scale to this day.

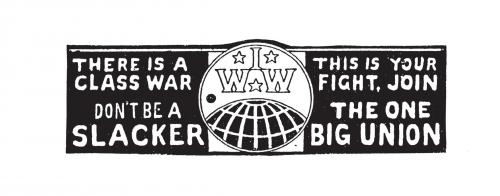

Its philosophy can be described as anarcho-socialist. Workers, organized into one big industrial union, would seize the means of production through a general strike and run the economy on a cooperative basis. Voting was a waste of time under capitalism, and no government would be necessary under socialism.

The IWW made absolutely no distinctions among workers on racial, ethnic, or religious lines, welcoming whites, blacks, Mexicans, the native-born, and immigrants, including the Chinese who were shunned, if not despised, by the mainstream American Federation of Labor and were even mistrusted by the Socialist Party. The IWW published its literature in a multitude of languages, including Yiddish.

A remarkable IWW poster, evidently from the mid-1920s or later, warns workers against the Ku Klux Klan on the grounds that it is “anti-Jew, anti-Negro, anti-Catholic, anti-foreigner, and anti-labor” leaving no doubt where the IWW stood on the plagues of anti-Semitism, racism, religious bigotry, and xenophobia.

Could the IWW have done more? In its opposition to big business and imperialist war, it never blamed Jewish bankers. Perhaps it did not specifically denounce Henry Ford’s publication of The International Jew in 1922, but neither did the American Federation of Labor led by the Jewish Samuel Gompers. Gompers also supported the severe restrictions on immigration from Eastern Europe, enacted in 1924, that endangered millions of Jews facing persecution. The IWW, on the other hand, welcomed foreign-born workers, including Jews, with open arms.

The IWW did not have many Jewish members because it did most of its organizing among workers in heavy industry or out west, among miners, agricultural workers, maritime workers, longshore workers, and lumberjacks. Some of these were migratory laborers. These were not occupations that attracted Jews. Of the few Jews living out west, most tended to be peddlers, merchants, and shopkeepers. The workers among them were employed mainly in the garment industry or in other skilled trades in the cities.

Yet one of the five known victims of the 1916 Everett Massacre in Everett, Washington, was a Jew. Nineteen-year-old Abraham Rabinowitz joined hundreds of Wobblies who hired a boat in Seattle to transport them to Everett, where they planned to launch a “free speech fight” demanding the right to speak on street corners in support of labor organizing. They were met with police gunfire as the boat attempted to dock. Some were shot, others drowned. The IWW press eulogized Rabinowitz as one who was “born of a race without a flag, a race oppressed by the intolerance and superstition of the ages, and died fighting for the brotherhood of man.” (See Philip Foner, The Industrial Workers of the World (1965), 534-35.)

The IWW’s headquarters was in Chicago. Although it did not represent many workers there, it had a considerable presence among hobos, who were essentially migrant laborers. During the warmer weather, they would hop freight trains to take them to jobs further west, returning over the winter to Chicago, where there were many flop houses and soup kitchens.

Beginning in 1908, it was in Chicago that Dr. Ben Reitman found housing for hobos and organized a Hobo College, featuring lectures and other educational programs, in which hobos themselves participated. Reitman had hoboed around as a teenager and was so enamored of their way of life that in his later years he wrote a work of fiction that purported to be the memoirs of a female hobo, Sister of the Road: The Autobiography of Boxcar Bertha as Told to Dr. Ben Reitman (1937). In it, the fictional Bertha describes her encounters with a variety of types, including Wobbly organizers.

Reitman was best known as the manager and lover of anarchist Emma Goldman. His brief but intense involvement with the IWW occurred in San Diego in 1912, when he and Goldman arrived to lend their support to an earlier “free speech fight.” A mob of vigilantes dragged him from his hotel room and forced him into a car. He was brutally tortured and dumped 20 miles out of town in his underwear. None of his attackers were charged with a crime.

Reitman also lectured on sexual health and was a strong advocate of birth control. He went into Chicago’s brothels to treat prostitutes for venereal disease and perform abortions. His advocacy of birth control landed him in jail.

Only in the IWW’s forays into the East, most notably the famous 1912 Lawrence, Massachusetts, textile workers strike and the 1913 Paterson, New Jersey, silk workers strikes, was there significant Jewish participation. Hannah Silverman, a 17-year-old Paterson mill worker, became an important strike leader in the silk workers’ struggle.

Mathilda Robbins, born Tatiana Rabinowitz, led a strike of textile workers in Little Falls, New York, in 1912. She was one of two paid IWW female organizers. During the 1920s, she was active in the IWW Sacco-Vanzetti Defense Committee. She wrote a column and contributed poetry to the IWW press and, in later years, became a social worker in Los Angeles.

Minnie Corder, a Jewish immigrant, was one of a few female Wobbly soapbox orators. Her turf was the Lower East Side of New York City and other Jewish working-class neighborhoods on the East Coast. Before joining the IWW in 1919, she participated in garment workers strikes in Boston in 1913 and 1915 and became a Socialist Party activist. She stuck with the Wobblies for the rest of her life.

Perhaps the best known Jewish Wobbly was Frank Tannenbaum. He organized unemployed workers in New York City to demand food and shelter from churches during the bitter cold winter of 1913-1914. He was falsely accused of incitement to riot and served a year in a notorious city prison, where he organized a strike of inmates against harsh conditions. After World War I, Tannenbaum dropped out of the labor movement to pursue a higher education. He earned a PhD from Columbia University and became a scholar specializing in race relations, criminology, and Latin American history.

Irving Abrams joined the IWW as a teenager in Rochester, New York, where he met Emma Goldman. Moving to Chicago, he found work in the garment industry, where he participated in a general strike led by the Amalgamated Clothing Workers in 1915, in which he was arrested 39 times. In 1920, he became an attorney specializing in civil liberties cases. He is best known for his role in the association that preserved the monument in a Chicago cemetery honoring the Haymarket martyrs and provided support to their families, duties he diligently carried out until 1971. His Jewish affiliations included the Workmen’s Circle, the Jewish Labor Committee, and the Hebrew Immigrant Aid Society. Abrams wrote a memoir, Haymarket Heritage (1989).

Abrams was the product of an improbable marriage—both his parents were converts to Judaism who met in Europe before immigrating to the United States. Ironically he may have been the most Jewish of Jewish Wobblies.

Meyer Friedkin was one of the few Wobblies said to have been on close terms with songwriter and poet Joe Hill, who was executed for murder, on false charges, in Utah in 1915. Friedkin was convicted of conspiracy in 1918 in the mass trials targeting the IWW and sentenced to 10 years in prison. There was even a half-Jewish, half-Indian Wobbly organizer known only as “Lone Wolf,” who was involved in the Wheatland farm workers strike in California in 1913, in which three people were shot dead, and was active in Chicago during the 1920s.

The best known Wobbly of all (except for Joe Hill), William D. (Big Bill) Haywood, had a Jewish lover known as B. Shotac. The daughter of Russian immigrants, she was employed as a public school teacher. He stayed in her apartment when he visited New York City, and it was there that the pageant to publicize the Paterson silk strike of 1913 was conceived by Mabel Dodge and John Reed. Haywood died in 1928 in the Soviet Union, where he had fled to escape government prosecution.

Although not technically a Wobbly, Archie Green, the son of secular socialist Jewish immigrants, is considered the premier “laborlorist” of the IWW. He corresponded with and interviewed aging Wobblies, collected original documents and other ephemera, co-edited The Big Red Song Book of Wobbly songs, and wrote a book on Wobbly culture. Franklin Rosemont, a Wobbly himself, dedicated Joe Hill: The IWW and the Making of a Revolutionary Working Class, his 2003 work on Joe Hill and the cultural impact of the IWW, to Green, dubbing him “the Shakespeare and Hegel of laborlore.” That is quite an encomium.

Three of the major historians of the IWW were also Jews: Melvyn Dubofsky, Philip Foner, and Joyce Kornbluh. The introduction to Kornbluh’s anthology, Rebel Voices, was written by IWW activist and keeper-of-the-flame Fred Thompson (not Jewish).

There is another side to this story. The Socialist Labor Party, one of the founding members of the IWW with a considerable Jewish following, pulled out in 1908, bitterly attacking the IWW and forming a rival organization called the Detroit IWW.

In 1912, Boris Reinstein, acting on behalf of this rival organization, led a strike of textile workers in Passaic, New Jersey. His ability to speak five languages allowed him to communicate effectively with the multi-ethnic mill workers. But he was at odds with the regular IWW. When the strike failed, the two sides blamed each other. A refugee from tsarist Russia, Reinstein returned there after the 1917 revolution and became an official in the Communist International.

Yet the influence of the Socialist Labor Party was not entirely negative. Its leader, Daniel De Leon (Jewish, but not openly so) provided the theoretical underpinnings for the IWW at its founding convention. Until 1908, the SLP newspaper, the Daily People, was the only socialist daily to support the IWW without reservations.

SLP intellectuals who left the party, including two Jews, Justus Ebert and Austin Lewis, continued to advocate for revolutionary industrial unionism, the former as an IWW journalist and the latter as a spokesperson for the left wing of the Socialist Party friendly to the IWW. Ebert wrote The IWW in Theory and in Practice, the most reprinted of all IWW publications. Lewis wrote The Militant Proletarian, an outstanding work of Marxist theory embraced by the Wobblies.

However, when IWW left the Socialist Party in 1912 over the issue of “sabotage,” many of the SP’s prominent Jewish leaders were glad to see it go, and most SP Jewish members remained loyal. Jewish anarchists associated with the Workmen’s Circle and the newspaper Freie Arbeter Shtimme also proved to be hostile to the Wobblies.

The Jewish-dominated International Ladies Garment Workers Union fought the Wobblies tooth and nail in the workplace. Gompers and the entire American Federation of Labor showed no mercy when the IWW was under siege during and after World War I.

On the other hand, the Amalgamated Clothing Workers (ACW), the second most powerful Jewish union, and one that did not join the AFL until 1933, engaged in some jurisdictional disputes with the IWW but welcomed its adherents and absorbed some of its radicalism. The best example is Joseph Schlossberg, who was an SLP stalwart before joining the ACW and becoming its secretary-treasurer. He brought with him a radical socialist orientation that stressed worker control and pushed the union to the left.

If the quintessential Wobbly was the unskilled industrial worker in the West—or the hobo—then it is hardly surprising that in the big picture, there were relatively few Jews among them. Historically, Jews are an urban people. Occupationally, Jewish workers gravitated to skilled trades. Yet American xenophobes and anti-Semites did not see it this way. Because Jewish immigrants to the United States were prominent in the labor movement and the left, their Christian detractors, influenced by the negative stereotype of the “wandering Jew” conflated them with the most hated and dangerous of radical organizations—the IWW. As Philip Webb wrote in his book Homeless Lives in American Cities: Interrogating Myth and Locating Community (2014), “The image of the immigrant Jewish radical is superimposed onto that of the native migratory hobo to combine threats to economic life and the bourgeois family in an anti-Semitic representation. … The Russian Jew thus becomes an easy symbol for the radical threat of homelessness.” To the WASP elite and a portion of the American middle class, “Russian Jews became the poster child for all radicals.” If evidence was required, the links between Emma Goldman and Ben Reitman—two demonized Jewish radicals—and the IWW was more than enough.

After the IWW’s decline as a labor union, it evolved into an advocate for revolutionary change. Sam Dolgoff embodied this evolution. Born in 1902, he was a painter by trade but spent part of his youth as a hobo. During the Depression, he served the Wobbly cause as a soapbox orator and organizer in New York City. He was a dissident in the AFL Painters Union. During the Spanish Civil War, he raised money for the Spanish anarchists. In 1954, he and his wife Esther formed the Libertarian League, an organization that attracted a Wobbly following. During the 1960s he spoke up for Cuban labor activists imprisoned by Castro. He also wrote books on anarchism. In the last decades of his life, Dolgoff became a living link between the old libertarian left and the New Left, sharing his memories and opinions with members of Students for a Democratic Society and other young radicals, as a speaker at college campuses. He died a rebel in 1990.

The influence of the IWW on the counter-culture of the 1960s and 1970s was felt in The Living Theater, an avant-garde troupe of actors led by two Jewish anarchists and Wobblies, Julian Beck and Judith Malina. The Living Theater itself became an IWW affiliate and raised money for the organization by holding a benefit.

Anarchist, internationalist, and pacifist Fredy Perlman was among a group of left libertarians who established a printing cooperative in Detroit in 1970 that published Black and Red magazine and other like-minded literature. The co-op became an IWW local. Perlman designed its union label which called for the abolition of the wage system and the state and “all power to the workers.”

Over 2004-2005, the IWW made history by organizing baristas at the Starbucks retail chain across the United States. The campaign’s co-founder was Daniel Gross, an attorney who co-authored, with Staughton Lynd, Labor Law for the Rank & Filer (2008) and was a member of the National Lawyers Guild Labor and Employment Committee. He is currently working with Brandworkers, organizing retail and food-service employees in New York.

Based on primary research, Franklin Rosement wrote in 2008 that “in recent years an impressive number of labor activists, radical environmentalists, socialists, anarchists, feminists, pacifists, poets, puppeteers, novelists, artists, musicians, cartoonists, and historians have concluded … that of all revolutionary and labor organizations in U.S. history, the IWW is the single most important inspiration and model—or at least one of the top two or three—for a new revolutionary movement in our time.”

As it turns out, I was recently in touch with Diane Krauthamer, the outgoing editor of the IWW newspaper the Industrial Worker. She told me that she is Jewish. If Rosemont was right, there should be more than a few young Jews like her. To borrow a phrase from the 1968 worker and student uprisings in France, la lutte continue (the struggle continues).

Leave a Reply