November 20 marks the anniversary of the Mexican Revolution of 1910‐1920. The party created by that event, the Institutional Revolutionary Party (PRI), is in power today. Yet, over the last nine years 60,000 people have been killed and 25,000 forcibly disappeared in the drug wars, while more than half the population lives in poverty. Foreign investment pours into Mexico to take advantage of wages lower than China’s, while the country is controlled by a handful of billionaires. One has to wonder: What happened to the Mexican Revolution?

The dictator Porfirio Díaz, who ruled Mexico from 1876 to 1910, caused the revolution. He and his cabinet of wealthy landowners and businessmen took land from the peasants and violently repressed any dissent. They also invited foreign capitalists from the United States, Britain, and France to invest in Mexican mines, railroads, oil, and agriculture until foreign corporations controlled much of the economy.

In 1906, anarchist revolutionary Ricardo Flores Magón of the Mexican Liberal Party organized armed uprisings accompanied by strikes that shook but did not topple Díaz’s dictatorship. Four years later, Francisco I. Madero, a wealthy landlord and industrialist, ran for president against Díaz but ended up in jail. Escaping, he called upon the people to rise up in revolution on November 20, 1910.

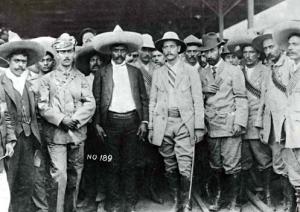

Madero represented the modernizing bourgeoisie of Mexico, northern farmers and manufacturers influenced by U.S. capitalism who resented Díaz and his cronies cornering the market. When Madero called for revolution, not only the Mexican business class but also the plebeian classes, heard him. Ranchers, peasants, factory workers, miners and railroad workers picked up the gun and rode with Francisco “Pancho” Villa and Emiliano Zapata. The nation rose up and drove Díaz from the country.

In Mexico’s first‐ever democratic election in 1911, Madero won the presidency, but his moderation and temporizing failed to satisfy the peasants and workers, while his suggestion of reform outraged the old ruling elite. Mexican conservatives, with the collusion of the U.S. ambassador, overthrew and assassinated Madero and put

Victoriano Huerta in power in 1913. In a second wave of revolution, led by another northern landlord and businessman, Venustiano Carranza, the forces of Villa and Zapata were again victorious and Huerta was toppled.

The revolutionary forces then divided: modernizing capitalist state builders led by Carranza against the plebeian armies of Zapata and Villa. The great irony of the revolution is that Carranza made an alliance with the anarchist House of the World Worker to provide troops in exchange for recognition of workers’ unions. So workers went off to fight peasants and lifted the modernizing capitalist to power.

Carranza, however, failed to satisfy workers and peasants with his new government, and was soon overthrown by General Álvaro Obregón. Obregón and his successor Plutarco Elías Calles were finally able to end the violent stage of the revolution by 1920 on the basis of concessions to the society’s underdogs.

The revolution had been fought over four fundamental issues: peasants’ demands for land, workers’ demands for unions, society’s demand for education, and the nation’s demand to control its natural resources. The Constitution of 1917 responded to all of those issues, but no action was taken on them until 1934 when Lázaro Cárdenas became president. Cárdenas carried out a massive land distribution, recognized the labor unions, and seized and nationalized Standard Oil and Royal Dutch Shell in Mexico. Schools were built throughout the country. So, one can say that the revolution was finally accomplished and fulfilled in 1940, improving the lives of millions.

Cárdenas also reformed the state, incorporating into the ruling party the Confederation of Mexican Workers, the National Peasant Confederation, and the public employees’ unions. The PRI government became a one‐party state. When Cárdenas stepped down in 1940, he was succeeded by conservative leaders who favored foreign and domestic business over Mexico’s working people.

By 1960, Mexico faced new problems. The population grew dramatically and millions moved to the cities. Modernization created new social classes. Now, there were not just peasants, ranchers, and industrial workers, but also white‐collar workers, university students, technicians, and new layers of management. The PRI’s one‐party state was challenged, and when students demonstrated in 1968 on the eve of the Olympic Games, demanding democracy, the government killed hundreds. A new left developed in Mexico in the 1970s, organizing among students, peasants, and workers; the government responded by disappearing some 500 in the country’s “dirty war.”

Beginning in the 1980s, the PRI adopted neoliberal policies, and Cuauhtémoc Cárdenas (son of Lázaro) led a split in an attempt to preserve the nationalist economic model. Though Cárdenas won the 1988 election, computer fraud put Carlos Salinas of the PRI in the presidency. Still, resistance persisted. In January 1994, the Zapatista Army of National Liberation led an uprising in an attempt to overthrow the government, but its rebellion was contained in the state of Chiapas.

Not allowed to elect a president from the left, to break the power of the PRI the Mexican people voted for Vicente Fox of the conservative National Action Party (PAN), who became president of Mexico in 2000. Fox proved a failure for his own party and for the people of Mexico. Andrés Manuel López Obrador, populist leader of the Party of the Democratic Revolution (PRD), challenged him and won the 2006 election, but, despite massive protests, vote fraud kept him from power. Felipe Calderón became president and launched his war on the drug cartels, unleashing the terrible violence that has taken so many lives.

So, in 2012 Enrique Peña Nieto was elected president and the PRI was back in power, passing a neoliberal program of education, labor, and energy counter-reforms. His government has not gone unchallenged. The murder of six and kidnapping of 43 students of the Ayotzinapa Rural Teachers College in September 2014 led to massive demonstrations against the government. At the same time, Mexican teachers have been striking against the education reform program. Still, though Mexico surely needs another revolution, the forces that might bring it about have not yet developed.

*Dan La Botz is a teacher, writer, and activist, editor of Mexican Labor News and Analysis, and a member of Solidarity. This article first appeared on the Democratic Left blog.

Leave a Reply