Collapsing wages, food shortages, and rampant inflation have led to growing hunger and desperation in Venezuela. Recent videos illustrate just how desperate the situation has become, as hungry people chase down livestock in the fields to butcher it for its meat, or skin dogs and cats on the streets of Caracas. Violent food-related protests have erupted in various cities around the country, and the looting of grocery stores is becoming more and more widespread. Meanwhile, thousands of Venezuelans are flooding across the borders into neighboring countries.

Maduro’s defenders on the left have basically turned a blind eye to this situation, claiming that mainstream reports are exaggerated, and assuring that the situation is the result of an “economic war” waged from the capitalist class and the United States. In their view, the current crisis is just another example of US imperialism and capitalist interference with a leftwing government in Latin America, a conspiracy to topple the socialist experiment by making the economy “scream” like Chile in 1973.

Others admit Maduro deserves some of the blame, but claim he has been limited in his ability to act because of the fall in oil prices and a campaign of sabotage from the right-wing opposition. Supporting the current regime as a bulwark against imperialism and the neoliberalism of the opposition is still the best option, they assure.

However, while it is true that Washington and local capitalists have long sought to undermine and overthrow the Chavez government, a closer look at the current crisis shows that a supposed “economic war” has very little to do with it. Nor does it have much to do with falling oil prices.

In fact, the primary cause of growing hunger and desperation in recent years are the government’s very own policies, which are under direct control of President Maduro himself, and could easily be rectified if the ruling elites so desired. But the policies remain in place, and the reason is pretty straightforward: corrupt government insiders are benefiting enormously from them.

As ordinary Venezuelans scramble to survive, Maduro and his friends are lining their pockets with oil dollars. Yet, inexplicably, many among the international left continue to give them their support.

“Thieves with no ideology”

At the crux of the crisis is Venezuela’s currency control system, which began under Hugo Chavez as a way to restrict access to foreign exchange, and ensure the government had enough dollars to import priority goods like food and medicine.

Like previous attempts at fixed exchange rates in Venezuela, there was some corruption and abuse of this system under Chavez. But it wasn’t until Maduro came to power in 2013 that things really started falling apart.

“A gang was created that was only interested in getting their hands on the country’s oil revenue,” says Hector Navarro, former Chavista minister and socialist party leader.

“They are thieves with no ideology,” he added.

Chavez’s former finance minister, Jorge Giordani, has said the same, estimating that some $300 billion have been embezzled through the foreign exchange system in recent years. Both Navarro and Giordani were long time members of Chavez’s inner circle, and mainstays of his cabinet until they became critical of Maduro in 2014 and were sacked.

Longtime Chavista insider Mario Silva also warned about this very thing after Chavez’s death in 2013. In a leaked audio recording, he claimed that a group of corrupt officials headed by then Vice President Diosdado Cabello were gaining the upper hand within the government, and they were “bleeding” the country of its dollar reserves.

This made Giordani’s dismissal in 2014 especially noteworthy, as he was the primary person in charge of keeping the currency regime in check, making periodic adjustments to avoid major distortions. Once Giordani was out of the way, the currency was allowed to get increasingly overvalued, greatly benefitting the “gang of thieves” and their foreign exchange schemes.

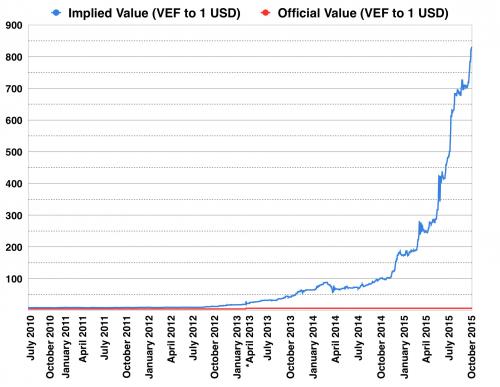

The basic scheme goes like this: those who can get access to foreign exchange at the cheap official rate set by the government, then simply turn around and sell those dollars on the black market for an extraordinary profit, or deposit them in bank accounts abroad. The greater the distance between the black-market rate and the official rate, the more profitable the scheme becomes.

Since 2013, Maduro has allowed rampant inflation to continually erode the value of the currency, refusing to make any significant adjustments to the exchange rate. As a result, the going rate for dollars on the street is now thousands of times higher than the rate at which the government sells them, creating huge incentives for illicit activities.

As a result, hundreds of millions of dollars have disappeared in goods that are never imported, infrastructure that is never completed, and briefcase companies that don’t exist. Instead of using the incoming oil dollars to pay for needed goods and services, government officials and their associates in the private sector simply abscond with them, leaving ordinary Venezuelans to deal with the consequences.

Numerous examples have come to light in recent months. The common denominator in these cases is that those involved usually have close ties to the Maduro government—a necessary ingredient for acquiring dollars at the official rate.

Even President Maduro and his vice president El Aissami have apparently gotten in on the fun. According to the former attorney general, a company owned by El Aissami was granted $120 million last year to import food from Mexico, while another $340 million were approved for a company with ties to Maduro.

All in all, the two companies received nearly half a billion dollars at the official rate of exchange, which was only one percent of the real value of the dollar at the time. Whatever food they imported was then sold in Venezuela at more than twice the price they had paid in Mexico.

There’s no wonder why Maduro and gang aren’t interested in fixing the distorted currency system. It allows them to funnel massive amounts of oil dollars into their own pockets, while profiting off food shortages in Venezuela.

Squeezing the poor

These same currency distortions are the primary cause of the current economic disaster. With so much of the oil revenue being misappropriated through the currency system, or sent abroad in the form of debt payments, there is very little money left over for the needs of ordinary Venezuelans.

But instead of fixing the currency distortions, or defaulting on the debt, the solution for Maduro has been to impose austerity on the country. And he has done so at a level that would put any neoliberal government to shame.

Since 2012, imports have been cut by over 65 percent, even amidst severe shortages of food and medicine. Social spending has also been cut drastically, with overall government expenditure reaching a lower percent of GDP than during the neoliberal years of the 1990s.

The results of these cuts have been very predictable: a collapsing health system and widespread shortages of food and medicine. Infant mortality and maternal deaths have skyrocketed, and thousands of preventable deaths have occurred as basic medications and medical supplies are frequently unavailable to those whose lives depend on them.

The lack of funds has also forced the government to ramp up the printing press in order to create the money they need to make up budget shortfalls. But printing money with no backing greatly exacerbates inflation, and erodes wages, sending people’s income downward while prices continue upward.

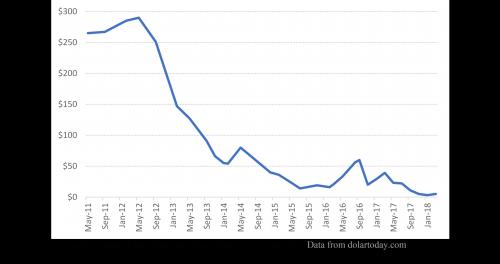

Since 2013, wages have declined by more than 90 percent in real value as runaway inflation has been met with inadequate wages hikes from Maduro. The national minimum wage has gone from the equivalent of about $300 per month in 2012 to about $5 per month today. In other words, the roughly 40 percent of the Venezuelan population that earns the minimum wage is now scrambling to get by on less than $5 per month!

Meanwhile, food prices have continued to spiral upwards at an astounding rate. Though the government uses price controls to combat inflation, widespread trafficking of goods means they can seldom be found at regulated prices. With the drastic cuts in dollars approved for imports, business owners import goods with dollars they acquire on the black market, and, therefore, they sell the goods at black market prices.

The result is that a single food item like a carton of milk or a pound of meat can cost as much as half the monthly minimum wage. Venezuelans often spend hours in line to buy food, only to find that their monthly salary will only afford them two or three items in the grocery store.

As might be expected, this has caused growing hunger and malnutrition. Hundreds of thousands of Venezuelans are now flooding into neighboring countries in search of basic necessities, or to start a new life there. Others attempt the risky and often deadly trip by boat to nearby islands.

Workers are also leaving their jobs en masse as their salaries have essentially become worthless. As a result, major sectors of the economy are now critically understaffed, only worsening what is by far the worst economic crisis in Venezuelan history.

A litany of excuses

Maduro and his defenders point to a number of factors to deflect blame for this situation—from the “economic war,”, to low oil prices, to US sanctions. But none of these excuses holds much water.

The capitalists and food traffickers that are accused of sabotaging the economy are actually just following the incentives set up by government policies, and are often well-connected insiders themselves. In fact, some of the worst food trafficking has been shown to be people inside the government, including the military, proving that the motivation is economic, not political.

Meanwhile, it is the government and the government alone that controls the exchange rate, and the allocation of oil dollars, making this a fairly easy problem to solve. But despite constant calls to fix it, Maduro has insisted on maintaining an extremely overvalued currency, and has continued to hand over the oil dollars to those who squander them while cutting imports, wages, and social spending for the poor.

As for falling oil prices, this has only exacerbated what Maduro’s policies were already causing. By the time oil prices fell in late 2014, the economy had already been contracting for three straight quarters, real wages had already dropped 80 percent, and imports had been cut by 25 percent. The growing inflation, food shortages, and currency distortions at the root of the crisis all began in late 2012, two years before oil prices had fallen.

The same goes for US sanctions, which had a negligible impact until Trump imposed broader sanctions last year. By that time, Venezuela’s economy had been in a free fall for four straight years.

In other words, it makes little sense to try to point the finger at things that did not occur until well after the crisis was underway. While sanctions and low oil prices have certainly exacerbated the problems, the truth is that Maduro’s own policies have ruined Venezuela’s economy far more than Washington or the opposition could have ever dreamed possible.

Lessons for the left

Venezuela’s collapse has some important lessons for the left. But in order to grasp them, there must be an honest accounting of what went wrong.

Many have insisted on viewing the enemy of their enemy as their friend, and so have continued to defend the Maduro regime, and deny the extent of the current disaster. Insisting that things would be worse under the neoliberalism of the opposition, they ignore the brutal austerity that Maduro himself has imposed, and shrug at the fact that the country is now poorer in per capita terms than at any time in the last 40 years.

But for those willing to take an honest look at the evidence, there is little point in trying to minimize the magnitude of the crisis, or the government’s role in it. Instead, we should attempt to learn about what went wrong, so that the left doesn’t keep repeating the errors of the past.

The first lesson to be learned is that leftist projects in developing countries need to take the problem of economic development more seriously. Though Chavez placed much emphasis on social programs for the poor, and anti-imperialist alliances abroad, he did not give the problems of the domestic economy the attention they deserved.

His approach to the economy generally involved the state taking over key sectors, with the notion that state control would remedy the problems of underinvestment by the private sector. Firms were often expropriated on a whim, and endless state-owned endeavors were launched without giving them careful thought or planning.

This led to a very bloated state bureaucracy, widespread corruption, and a long-term decline in production in key sectors, which became a major drain on state revenues and economic growth. State owned enterprises often ended up in the hands of corrupt bureaucrats who made them into their own private domains, and then milked them dry.

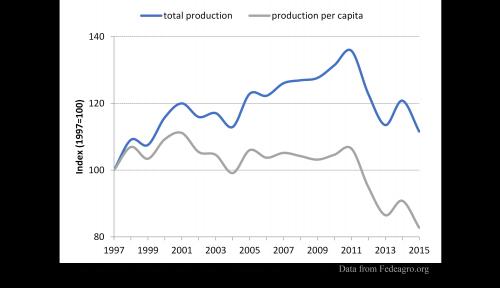

One notable example of this was in 2010, when Chavez launched a major offensive in the agricultural sector. Hundreds of large farms were expropriated, along with multiple food processing industries.

Given that the farms and industries were often undercapitalized and unproductive, state intervention was the right approach. But most of the enterprises that were expropriated were then handed over to state officials and bureaucrats who had little preparation or oversight. The result was complete mismanagement, leading to a drastic decline in food production in the years that followed, and a worsening of food shortages.

The lesson here is that state takeovers of major sectors of the economy are not necessarily a good idea in poor countries with weak institutions. These types of interventions must take into account the organizational capacity of the state to administer enterprises without running them into the ground, especially in sectors that are so crucial to the national economy.

One alternative might have been to turn control of these enterprises over to workers. And, in fact, there was a proliferation of community and workers’ organizations under Chavez. But the government did not do this in most cases, and here lies another important lesson for the left.

While increasing worker power and control over production should be a major goal of any socialist project, to be successful workers and social movements must build organizational power that is independent from political parties and the state.

In Venezuela, the communal movement was very much a state-sponsored initiative, with local communes and community councils usually following directives on how to organize from above. The extent of their power and control over production was decided by the government, not workers.

This resulted in the communes being used as mechanisms of patronage and control rather than vehicles of liberation. Nowadays, members of these organizations get certain perks and benefits from the government, but come election time they are forced to vote for the government candidates to avoid losing those benefits.

Finally, there is an important lesson here on the question of reforming liberal democracy. Though Chavez was justified in his criticisms of Venezuela’s previous two-party system, and the fairly exclusionary kind of democracy that existed in the country before 1998, in attempting to dismantle and transform this system, he ended up creating something even worse.

Virtually all organs of the state, including the courts, the electoral body, and the military, were stacked with party loyalists, and yes-men that were valued more for their obedience than their competence. As a result, the institutions became rubber stamps for orders coming out of the executive. This was often justified by pointing to the fact the institutions were never really independent under liberal democracy either, and so the abuses under Chavez never seemed too consequential.

However, when Chavez died, and Maduro’s “gang of thieves” gained the upper hand inside the government, there were no longer any checks on their power. The lack of any independent institutions allowed them to force out internal opponents, neutralize the congress, hold fraudulent elections, and form an all-powerful body that now runs the country as they please.

Instead of making liberal democracy more inclusive and democratic, Maduro and gang have transformed it into a kind of authoritarianism that now deports journalists, jails union leaders, detains online activists, murders whistleblowers, and tear gasses the poor and hungry. What once was one of best electoral systems in the world has now been stripped of all the guarantees that ensured free and fair elections, allowing Maduro and gang to bend everything in their favor.

All of this should serve as an important lesson for the left—that despite the major limitations of liberal democracy, having some checks and balances is better than none. Had Chavez allowed more room for independent institutions, and permitted real checks on the power of the presidency, Venezuela might not be in the mess it is today.

As the country heads into another very questionable electoral process, the left should not throw its support behind the corrupt and authoritarian Maduro regime, nor should it support the US-aligned right-wing opposition. Our support and solidarity should instead be with the Venezuelan people, and their right to democratically elect their leaders. That is the only possible solution to the crisis.

Chris Carlson is a PhD candidate in Sociology at the CUNY Graduate Center. His research is on the sociology of development, with a focus on agrarian relations and structural transformation in the Global South.

Leave a Reply