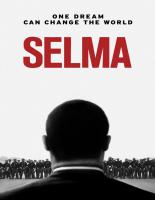

By: Ava DuVernay

2015

In Ava DuVernay’s film Selma we first meet Martin Luther King Jr. as he’s preparing to accept the 1964 Nobel Peace Prize in Oslo. Minutes later he’s in the Oval Office with President Lyndon Johnson unsuccessfully pressuring the president to introduce voting rights legislation. Not too long after, he’s in a church basement discussing how to provoke a confrontation between a segregationist county sheriff and the Black community of a small Alabama city.

The opening half-hour of Selma deftly cuts to the core of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference’s (SCLC) strategy under King’s direction. The movement’s power came not from celebrity—or even oratory—but through provocation, disruption, political division, and open, ugly conflict. The King that urges the movement to “negotiate, agitate, resist” in the film is a far cry from the sanitized King of American history textbooks and traditional MLK Day parades.

By delivering this long-concealed King to the public, DuVernay has made a tremendous contribution not only to American cinema, but to the Black Lives Matter movement that is still gaining its footing. DuVernay’s refusal to make Selma into a hagiography or a one-man show makes it one of the few honest portrayals of a movement that America has purposefully mis-remembered. It also allows DuVernay to share the true roots of King’s successes with a new generation of activists.

And yet, while DuVernay skillfully depicts the contentious relationship between King and LBJ, as well as the brutal violence inflicted by police and white vigilantes, Selma leaves out another crucial aspect of the SCLC’s strategy in each of its southern campaigns: the fracturing of the white power structure in the segregated South and in the New Deal coalition nationally. We see King extolling the power of “drama” in putting pressure on the West Wing, but little attention is given to how the SCLC’s campaigns skillfully took advantage of a slowly changing South and shattered alliances between northern liberals and southern segregationists. The SCLC did both to further their ultimate aims, and they made few friends doing so.

One film can’t show it all, of course, and the gradual pulling apart of a political coalition probably wouldn’t be great cinema. But today, young activists are constantly being urged to avoid conflict and work within a broken system. More than anything, these activists need to know that the most successful civil rights activists at the height of their power ignored similar admonitions. The best organizers of the civil rights movement understood that their campaigns had to tear at the fabric of a hostile society, not meld into it. This involved extensive knowledge of local political and economic conditions, and they knew it meant exposing fair-weather allies to extreme political risk.

The SCLC’s strategy was rooted not just in high-level negotiations, but also in antagonistic engagement with the political-economic order of the Deep South. The segregated South in the 1960s was still undergoing a long-term economic transformation that began during Reconstruction. Reeling from decades of losses in agricultural employment, many southern cities were electing moderate segregationist mayors who pledged to attract industrial capital that was slowly abandoning the Rust Belt for warmer, less unionized climes. These officials were not as tethered to the traditional planter elites and were more concerned with portraying their cities as orderly, reliable, and employer-friendly. Enforcing segregation with vicious and unpredictable police violence was not a high priority. While most of these mayors still supported segregation, they often went to great lengths to avoid violent confrontation between police and demonstrators.

Selma’s Joseph Smitherman was one such mayor. Determined to avoid the reputation that Birmingham had earned during and after the 1963 demonstrations, Smitherman sought to deal with protesters in a way that would not attract the national media. Smitherman’s police chief, Wilson Baker, received orders to ignore an injunction blocking any meeting of three or more people discussing voting rights. This modicum of respect for the First Amendment allowed basic organizing to take place in the city, including the boisterous mass meeting in Brown Chapel depicted in the film. In smaller towns across the Deep South with more conservative elected officials, such meetings were often subject to brutal violence by vigilantes. Numerous murders of organizers, including the shooting of Medgar Evers referred to in the film, made such meetings more risky and rare than many now assume.

While Baker and Smitherman hoped to keep overt conflict to a minimum, County Sheriff Jim Clark, who controlled the County Clerk’s office and areas outside Selma’s city limits, had other plans. A hard-line segregationist, he guaranteed horrific violence towards demonstrators. Selma thus could offer a less hostile—though still dangerous—organizing environment as well as an assurance of confrontation. As King—expertly played by David Oyelowo—says in the film after being punched by an unnamed white man in a hotel lobby, “This place is perfect.”

But these “perfect” conditions made most outside observers uncomfortable—even those who professed sympathy for the SCLC’s cause. As they had in Birmingham, many tepid supporters of King urged him and the SCLC to side with the less reactionary political leaders in Selma and work with them to achieve the change that everyone agreed was inevitable.

Instead, the SCLC’s Selma strategy exploited the differences between the moderate Smitherman and the hard-line Clark as well as the constituencies they represented. The strategy pitted these competing factions against each other in order to create a massive, disruptive media event. This local disruption reverberated through state and national politics and exerted pressure on officials at all levels. Though the film touches on the local dynamics briefly, we only get a sense of how essential they were to the movement through references to the failed Albany Campaign of 1961-62, in which officials colluded to avoid dramatic confrontation. DuVernay shows us how King used chaos to get LBJ’s attention, but we learn less about the complex process of creating chaos that can effectively build power and bend elected officials to one’s will.

Without recognizing the deep power dynamics involved in the key civil rights campaigns, we can fall into the trap of thinking that King’s power flowed exclusively from moral suasion—that the images of southern Blacks beaten and killed by cops stirred the conscience of the nation. Many were stirred, and many joined the movement. But far more saw King’s activism as unnecessarily divisive and counterproductive. To them, the SCLC—and particularly King—were a bunch of agitating publicity-seekers, not brilliant strategists and tacticians. To be sure, much of white America and its political representatives thought the actions of southern police and vigilantes were excessive, but many people placed blame on both King and the segregationist establishment for the violence. Many members of the Black elite felt the same way.

By the time of the Selma campaign, Gallup polls* showed that a consistent plurality of Americans thought the government was focusing too much on civil rights for Blacks or moving too quickly to grant those rights. Nor was King a wildly popular figure. Polls from the 1960s showed that the percentage of respondents rating him as “highly favorable” never topped 20 percent. The percentage of respondents who labeled him “highly unfavorable” was always higher.

In short, moral suasion only got the Selma campaign so far. It was disruption and political threats to the Democratic Party that played a much larger role in delivering an impressive string of victories. While DuVernay comes closer to showing us this than any other popular illustrator of King and the SCLC, we don’t really get the full picture. Instead, we’re shown how brutal white violence delivered to King regular meetings with a wavering LBJ and caused trouble for Alabama Governor George Wallace. We see King’s “drama” unfold, and we see its positive results. But it is the links between that “drama” and political power that are still a bit gray.

This is perhaps best illustrated in a scene between LBJ and Wallace late in the film. They talk of being hounded by protesters, the urgency of change, and their political legacies. Wallace makes clear that he’s not changing his hard-line segregationist position; LBJ sides with the SCLC and shortly thereafter introduces the Voting Rights Act. While it is a powerful conversation, the scene doesn’t quite carry as much weight as it should. Both men knew that acceding to the SCLC’s demands meant the abandonment of the Democratic Party by southern whites. It meant breaking the political coalition that they had both risen on and that Democrats had painstakingly built and struggled to hold together. Selma doesn’t quite show us that. Instead it hints that through stirring drama and protest, politicians can be forced to change their positions. While this is partially true, it’s important to note that King and the SCLC were also wielding a serious political threat just in case moral suasion didn’t cut it.

For activists today, this is important to absorb. As the Black Lives Matter movement charges forward, it will undoubtedly be confronted with half-supportive mayors, governors, and presidents. It will be offered half-measures and weak concessions and will be diverted from its original, radical demands (fergusonaction.com/demands) by supposedly sympathetic politicians and commentators. It is at these moments that it will need the power analysis that King and the SCLC had.

The movement will also need to know how to communicate with a largely unsupportive public. It is perhaps the greatest shortcoming of Selma that we hear mainly from elected officials, civil rights organizers, and violent segregationists but get little sense of broader American public opinion at the time. We are presented with an honest and illuminating portrait of King and the SCLC without an equally honest depiction of how hostile most of America was to their actions. This is an essential part of the story because it could help dispel the insistent claims that Black Lives Matter is somehow different—more annoying, less focused, less historic—than the Selma campaign. More than anything, today’s young activists need to be reminded that these civil rights heroes were hated and scoffed at too—not just by reactionaries but by moderates and many liberals. This is important to keep in mind as a new generation “negotiates, agitates, and resists” and is met with admonishments to “be civil” and “go slow.”

Leave a Reply