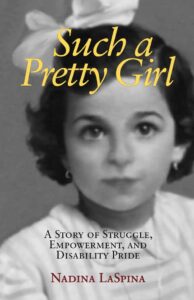

By: Nadina LaSpina

San Francisco: New Village Press, 2019

I haven’t met Nadina LaSpina, but I can easily imagine it. She radiates through her memoir, Such a Pretty Girl: A Story of Struggle, Empowerment, and Disability Pride. Shiny! Illuminating! Bright! Readers will hear her riotous laughter, the cooking-up of plans, and good listening. Her memoir is one-part of unapologetic exuberance and another part of clear-headed persistence.

I haven’t met Nadina LaSpina, but I can easily imagine it. She radiates through her memoir, Such a Pretty Girl: A Story of Struggle, Empowerment, and Disability Pride. Shiny! Illuminating! Bright! Readers will hear her riotous laughter, the cooking-up of plans, and good listening. Her memoir is one-part of unapologetic exuberance and another part of clear-headed persistence.

Nadina is apparently propelled by a cosmic energy towards disability justice. Throughout the decades, she has organized with Disabled In Action, ADAPT, and Not Dead Yet. Her memoir sketches the disability movement’s historical contexts by introducing us to its characters, including her friends, lovers, and comrades. She is, no doubt, a person you want to know to have in your corner—at your kitchen table and shoulder-to-shoulder on the streets.

Her memoir, however, doesn’t cast her as an inspirational leader. It doesn’t read as an account of her exceptional triumphs or a long list of her many accomplishments. This is important since, too often, disabled people are characterized as inspiring for succeeding “despite” their disability. Instead, the memoir recounts her struggle to build a life in a world that wants to erase bodies like hers. In her words, it took years to “learn how to fight against the violence done to us and many more years for the wounds to begin to heal.” (at 312)

The first chapters in Part I (‘Che Peccato: What a Shame’) recount Nadina’s early years in Sicily. Her father’s desperation to find a “cure” led to innumerable surgeries and, eventually, a double amputation. She also describes innumerable encounters with classmates, neighbours, and friends characterized by pity and mourning. This aligns with dominant conceptions of disability that prize independence and disparage the need for support. These pervasive stereotypes pressure disabled people to alter themselves to conform and function “normally” through cure, rehabilitation, and prosthetics. Beginning in the mid19th century, disability became associated with abnormality, and our social and economic worlds were organized around the search for the “normal”. Disability is considered a private burden, rather than its costs, the subject of state or collective support. The subjugation of disabled persons is not historical, and these stereotypes continue to be so pervasive that they often remain unrecognized as oppressive. Critical Disability Theory (CDT), however, characterizes disability as a universal human variation rather than an aberration. CDT explores the ableist assumptions of the bio-medical and charity models of disability and exposes their distinct historical and institutional underpinnings.

In Part II (‘Fighting Back’), Nadina recounts her experiences as a disabled student and the barriers she faced on campus as a graduate student and faculty member. On one occasion, a classmate proclaimed: “I don’t think of you as disabled,” as though it were a compliment. Indeed, disability’s place on campus remains contested, and students with disabilities are governed by bio-medical and charity models of disability. This section reminded me of Jay Dolmage’s Academic Ableism (2017) and his exploration of ableist attitudes, policies, and practices that are baked into Canadian post-secondary accommodation processes. Biological reductionism has long infiltrated Canadian campuses to identify “normal” learners and exclude those outside the bell curve.

Universities are neoliberal institutions, relying on various strategies to increase the role of the free market, marked by individualistic understandings of social problems. Pre-pandemic, Canadian universities faced brutal cuts from their conservative provincial governments in the name of modernization. For example, Ontario’s Progressive Conservative party has a long and violent history of violent cuts to social assistance. These cuts were never neutral and are, instead, intended to create a future without disability. In 2019, the Premier slashed tuition by 10 percent. Campuses had no way to make up for the lost revenue. Students with disabilities bore the brunt of cuts to services. Ontario’s provincial government took credit for improving access, even though tuition cuts help higher-income students as opposed to debt cancellation. The pandemic compounded the hostile environment for students with disabilities.

In Part III (‘Love and Activism’), Nadina tracks the evolution of the American disability rights movement(s) of the second part of the twentieth century. This Part smells haunting and verdant, a combination of heartache and celebration. Across the world, Disability Pride Marches are organized to resist ableism, disability violence, and disability oppression. Organizers often raise demands that go beyond traditional civil rights reforms, like enacting legislation or policy reform. They aim, instead, to dismantle structures and root causes of disability subjugation. They challenge presumptions that the best way to address disability exclusion is to gain inclusion in state institutions. Organizers adopt transformative resistance strategies, including mutual aid and the abolition of the institutions that warehouse persons with disability (prison, long-term care, child protection, group homes). In Toronto, disability movements have lost several key leaders recently, including Graeme Bacque and Don Weitz, whose work supported a “Mad turn” to Disability Pride.

Nadina’s memoir is also about connection, loss, and love, especially Part IV (“Come Sono Contenta: How Happy I Am”). She describes falling in love with Danny Robert, a fellow disability activist. Their love story is electric, but I found myself preoccupied with her relationship with her “blood sister,” Audrey, whom Nadina met in a New York hospital as a teenager. About Audrey and Nadina, Sister Angelica, at the convent where they went to school, pronounced: “This is your destiny; you can never be happy.” (at 91) Audrey died by suicide. At her funeral, the rabbi said Audrey had “stopped suffering” and that “she had suffered bravely all her life.” (at 92) Nadina writes: “No, no. I wanted to scream. Audrey was a lot of fun. Audrey and I had been so happy so many times… I was angry at Audrey for dying and at myself for being unable to stop her… Angry at everyone who had made Audrey believe she was better off dead.” (at 92)

These same presumptions about the inevitability of the suffering of disabled people have been used to justify the expansion of the criteria to access Medical Assistance in Dying (MAiD) in Canada. The restrictions on access to MAiD for persons whose sole source of suffering is related to their mental health are set to be removed this coming March. There are, however, terrifying barriers to mental health services and support in Canada (particularly non-coercive ones). Persons with mental health issues, like Audrey, might certainly have been, are without adequate support. There is also no protocol to confirm that persons with disabilities have been provided with viable alternatives before becoming eligible for MAiD. In April 2019, the United Nations Special Rapporteur on the Rights of People with Disabilities criticized the unavailability of “adequate safeguards to ensure that persons with disabilities do not request assistive dying simply because of the absence of community-based alternatives and palliative care.” Consider the “sinister implications” of the availability of MAiD to persons with disabilities, like Audrey, if it becomes an additional means of death and a substitute for assistance in living.

MAiD is a deeply feminist issue. Women with disabilities, often denied adequate support, are pressured to seek MAiD. The Disability Filibuster launched in March 2021 on International Women’s Day. It came together as a “last-ditch effort to stop the expansion of MAiD.” Organizers broadcast an ongoing live stream that featured disabled people and allies. Speakers testified about the impact of the changes to MAiD’s availability on Black, Indigenous, queer and poor communities, characterizing it as another form of cultural genocide. Indigenous communities, and organizations like the BC Aboriginal Network on Disability Society, advocate for services that support life, such as suicide prevention services. The expansion of MAiD contradicts this work, becoming a kind of “suicide assistance”.

In all, Nadina shines through this compelling book. It chronicles the struggles of people with disabilities to confront ableism, disability violence, and other forms of oppression. She illuminates a future course for disability justice movement(s). Such a Pretty Girl is an important and necessary contribution – a ‘must-read’ for anyone interested in modern reverberations of struggles for disability justice, including the eviction of encampments and a disability-centered response to COVID-19. At the same time, though, the book feels intimate rather than tactical or strategic. Nadina figured out a way to live well in a world that intended to exclude her. Her struggles feel familiar and deeply relevant.

Leave a Reply