The Pope in Mexico Criticizes the Government, Big Business, and the Church Hierarchy, While Siding with Working People, the Poor, Migrants, and the Indigenous

Pope Francis, during his six-day visit to Mexico in mid-February, criticized the country’s political and economic elite as well as the Catholic Church hierarchy for their preoccupation with wealth and power, while simultaneously expressing support for the country’s working people and the poor. The Pope’s presence in Mexico constituted an indictment of Mexico’s ruling elite and of the society of inequality, violence, and corruption that they have created.

The Pope also criticized Donald Trump and other Republicans who call for building a wall between Mexico and the United States calling their views "not Christian." Said the Pope: “A person who thinks only about building walls, wherever they may be, and not of building bridges, is not Christian. This is not the gospel.”

Without mentioning the term, the Pope revived the language and ideas of the Theology of Liberation of the 1960s and 1970s, while he also embraced the indigenous people and implicitly their social movements in Mexico. He was, however, criticized by the left for his failure to discuss the issues of priests’ sexual abuse of children, the issue of femicide (the murder of women), and the 43 Ayotzinapa Rural Teachers College students who were disappeared in September 2014.

The Catholics remain the largest religious group in Mexico, some 83 percent, despite the growth in recent decades of Evangelical churches and other Protestant sects. While the Mexican state is officially secular and historically anti-clerical, in fact the government often favor the Catholic Church. During the Pope’s visit some officials, rather than shaking hands, even knelt and kissed the Pope’s ring, a Catholic obeisance.

Criticizing the Government and the Catholic Hierarchy

At a formal reception by Mexican President Enrique Peña Nieto, the Pope criticized Mexico’s economic elite and political leaders for the country’s economic inequality, lack of justice, and for creating the conditions that have brought about “corruption, drug dealing, the exclusion of different cultures, violence, human trafficking, kidnapping and death, causing suffering and impeding development.”

Speaking to the country’s Catholic hierarchy—bishops, archbishops, and cardinals, often called the “princes” of the Church—the Pope criticized religious “fundamentalism” and “triumphalism” and called upon the religious leaders to instead emphasize personal relationship to Christ. Many interpreted him as criticizing the hierarchy when he said, “We do not need ‘princes,’ but rather a community of the Lord’s witnesses. Christ is the only light; he is the well-spring of living water; from his breath comes forth the Spirit, who fills the sails of the ecclesial ship.” Speaking in Morelia, Michoacán, he told parish priests that they must not become “bureaucrats of the divine,” most “not become comfortable in the sacristy,” and must not “resign themselves to an apparently unchangeable system.”

Speaking to Workers, Migrants, and the Indigenous

The Pope held mass and spoke to crowds at several cities in Mexico, from the working class city of Ecatepec in central Mexico where he addressed a million people, to Chiapas in the South, one of the country’s most indigenous states, to Ciudad Juárez in the north (across from El Paso, Texas) where he spoke to audiences that included maquiladora workers. In all of his talks the Pope put special emphasis on the exploited, oppressed, and marginalized, whether the indigenous, factory workers, the poor, or migrants. He also spoke out everywhere against drug trafficking, corruption, and violence, as well as on the environmental threat of climate change.

Speaking in Juárez to several thousand, including many factory workers, he said:

“The dominant mentality puts the movement of people at the service of capital, leading in many cases to the exploitation of employees who are treated as if they ere objets to be used and thrown away. And we have to do everything possible to make sure that these situations don’t happen any more. The movement of capital cannot determine the movement and the life of people.

“What does Mexico want to leave to its children? Does it want to leave them the memory of exploitation, of inadequate wages? Of bullying in the workplace? Or does it want to leave them a culture of work with dignity, of a decent home, and land to work?”

In Chiapas, Mexico, the Pope asked the indigenous people for forgiveness. “How good it would be for all of us,” said the Pope, “to examine our consciences and to learn to say, forgive us. Today the world, despoiled by the throwaway culture, needs you.” He began his mass in Chiapas with a short reading of a Psalm in the Tzotzil language, spoken by many Mayan people in the region, and he also made mention of the Popol Vuh, of “Book of the Community” of the ancient Mayan Quiché people. While in Chiapas, Pope Francis also signed a decree authorizing the saying of mass in Náhuatl, the most widely spoken indigenous language in Mexico.

Reviving the Theology of Liberation

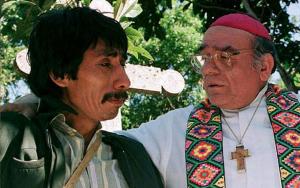

While in Chiapas, the Pope said a prayer at the tomb of Bishop Samuel Ruiz García (pictured below), a believer in the Theology of Liberation and best known for his role as a mediator during the Chiapas Rebellion of 1994 led by the Zapatista Army of National Liberation (EZLN).

Many conservatives accused him of encouraging and supporting the Zapatistas. The Theology of Liberation, with its “preferential option for the poor,” helped to inspire many progressive social movements in Latin America in the late twentieth century. Former Pope John Paul II and his right-hand man Cardinal Joseph Ratzinger (later Pope Benedict) worked systematically to eradicate the Theology of Liberation by firing professors, punishing priests, and closing down organizations inspired by that emancipatory philosophy.

Still, La Jornada, the Mexico City leftist daily newspaper, editorialized

“Without denying the force and the relevance of the Popes speeches, it’s necessary nevertheless to add that Francis avoided at all costs referring to three tragedies that are emblematic of the national reality today: the sexual buses committed by a number Catholic priests against minors, the scandalous persistence of femicide in the country, and the exasperating failure of the government to clear up the aggression carried out the year before last against the teachers college student from Ayotzinapa where 43 of them were disappeared and whose fate remains unknown to today.”

Despite these critical limitations, the Pope’s visit represented a condemnation of the Mexican political and economic order, a call for greater justice, and a demand that the working people, the poor, migrants, and the indigenous, who are today the last, should come first.

NICE

NICE