Puerto Rican socialist Rafael Bernabe calls for a Green New Deal in Puerto Rico, to facilitate its economic and ecological reconstruction.

Puerto Rico

Puerto Rican socialist Rafael Bernabe calls for a Green New Deal in Puerto Rico, to facilitate its economic and ecological reconstruction.

José A. Laguarta Ramírez presents an in-depth discussion of the history of the Puerto Rican radical left.

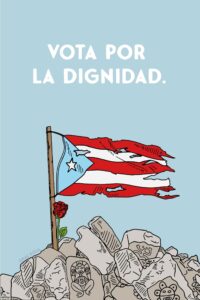

As the eyes of the world were fixated on the outcome of the U.S. presidential election, the U.S. colony of Puerto Rico produced a more satisfying and historic outcome for the left after its local election on Nov. 3, 2020.

Any attempt to address the electoral issue in Puerto Rico from a socialist perspective must begin by pointing out the limits of the electoral process in the island.

The United States has suffered 135,000 deaths from COVID-19 and has tens of millions of unemployed and both crises continue now into the fifth month, but nowhere has the economic crisis been greater than in the U.S. colony of Puerto Rico.

The passionate uprising that began in Minneapolis after police murdered George Floyd quickly spread across the country and around the world, is now the biggest upheaval since 1968.

As of May 4, Puerto Rico is reporting 1,806 confirmed coronavirus infections and 97 Covid-19 deaths. Compounding the public health crisis, recent natural disasters (hurricanes and earthquakes) and long-term neoliberal austerity have pushed the island’s people to the brink. But social . . .

Barricades block the entrance to the Governor’s mansion known as La Fortaleza in San Juan, Puerto Rico on March 18, 2020. – On Sunday March 15, Puerto Rico’s Governor Wanda Vazquez imposed a curfew and ordered the shutdown of most . . .

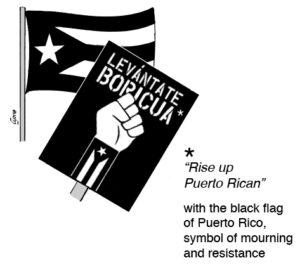

The summer of 2019 will go down as a major moment in Puerto Rico’s history. Between July 10 and 25, street protests—unprecedented in their intensity, persistence, diversity, and size—led to an unprecedented result: The Island’s highest government official . . .

Latin America is experiencing an abrupt change generated by enormous confrontations between the dispossessed and the privileged. This confrontation includes both revolts by the people and reactions by the oppressors.

The October Revolts

The uprising in Chile is the most important event . . .

For 14 days this summer, Puerto Ricans engaged in nightly protests that resulted in the ousting of Governor Ricardo Rosselló. The protests—which amassed nearly one-third of the archipelago’s population—were sparked by a leaked chat in which the governor and members . . .

The discredit attained by the dominant parties, by the legislature, by the “politicians” and even “politics” itself, defined inaccurately, but viscerally despised by many people, recalls the concept of “organic crisis” advanced by the Italian Marxist Antonio Gramsci. Authors such . . .

We express our solidarity with the people of Puerto Rico in their struggle against the corrupt government of Governor Ricardo Rosselló. This Friday marks seven days of massive protests demanding the resignation of the governor and his followers. In spite . . .

Police donning anti-riot gear—many with their names and badge numbers covered—used teargas, pepper spray, rubber bullets, and batons to dislodge protesters from the streets surrounding the Puerto Rican governor’s mansion in Old San Juan on Wednesday evening. Earlier that day, tens . . .

In 1898 the U.S. military invaded and seized Puerto Rico and Cuba during the Spanish-American War. Unlike Cuba, Puerto Rico has not yet achieved independence and the United States continues to exert political, economic, judicial, and military control over the . . .

Isolating the situation of Puerto Rico is one of the mechanisms used to seek acceptance of the austerity policies that are now being imposed on the Island.(1) If the crisis is seen as the result of actions by Puerto Ricans or their government — if the responsibility lies, exclusively or fundamentally, in Puerto Rico — then it is logical that it bears the consequences of its own deeds or misdeeds, painful as they may be.

Isolating the situation of Puerto Rico is one of the mechanisms used to seek acceptance of the austerity policies that are now being imposed on the Island.(1) If the crisis is seen as the result of actions by Puerto Ricans or their government — if the responsibility lies, exclusively or fundamentally, in Puerto Rico — then it is logical that it bears the consequences of its own deeds or misdeeds, painful as they may be.

Dear Friends:

Dear Friends:

By now you have surely heard about the catastrophic impact of Hurricane María in Puerto Rico, as well as the slow and still inadequate response by U.S. federal agencies, such as FEMA.

A month after María, dozens of communities are still inaccessible by car or truck. Close to 90 percent of all homes lack electricity. Half lack running water. Many of Puerto Rico’s 3.2 million residents have difficulties obtaining drinking water. The death toll continues to rise due to lack of medical attention or materials (oxygen, dialysis) or from poisoning caused by unsafe water.

(Normally my writing, especially when facing new situations,is the result of discussions with my comrades. But these days we are practically incommunicado. That’s why even more than in other cases, this article is entirely my responsibility. And, at the same time, I write with incomplete informatioin, the result of the same lack of communication, and therefore everything that I write is, even more than usual, subject to future correction. – RB)

(Normally my writing, especially when facing new situations,is the result of discussions with my comrades. But these days we are practically incommunicado. That’s why even more than in other cases, this article is entirely my responsibility. And, at the same time, I write with incomplete informatioin, the result of the same lack of communication, and therefore everything that I write is, even more than usual, subject to future correction. – RB)

Crises raise new, sharp problems that unveil and accentuate both the admirable and the negative aspects of the societies they affect. They also pose new tasks and offer new perspectives on already established plans. The case of Puerto Rico and the effect and response to the strike by Hurricane María is no exception.

With this dramatic announcement, Governor Alejandro García Padilla transformed the island nation’s long-simmering debt overhang problem into an international spectacle. A financial mess that seemingly concerned only institutional investors, municipal bondholders, and some hedge fund managers exploded into a full-blown debt crisis with disquieting parallels to the situation in Greece.

The situation at the University of Puerto Rico is framed within a context of a 10-year economic depression and unsustainable debt crisis, which was meant to be remedied by the 2016 Puerto Rico Oversight Management Economic Stability Act (PROMESA), signed by President Obama, and its federal Fiscal Control Board (Junta de Control Fiscal, the word Junta in Spanish is politically charged). Similar to what was presented at the conference this weekend regarding Greece, South Africa and Mexico, the public university became, throughout the second half of the twentieth century, a vehicle by which many people have escaped poverty.