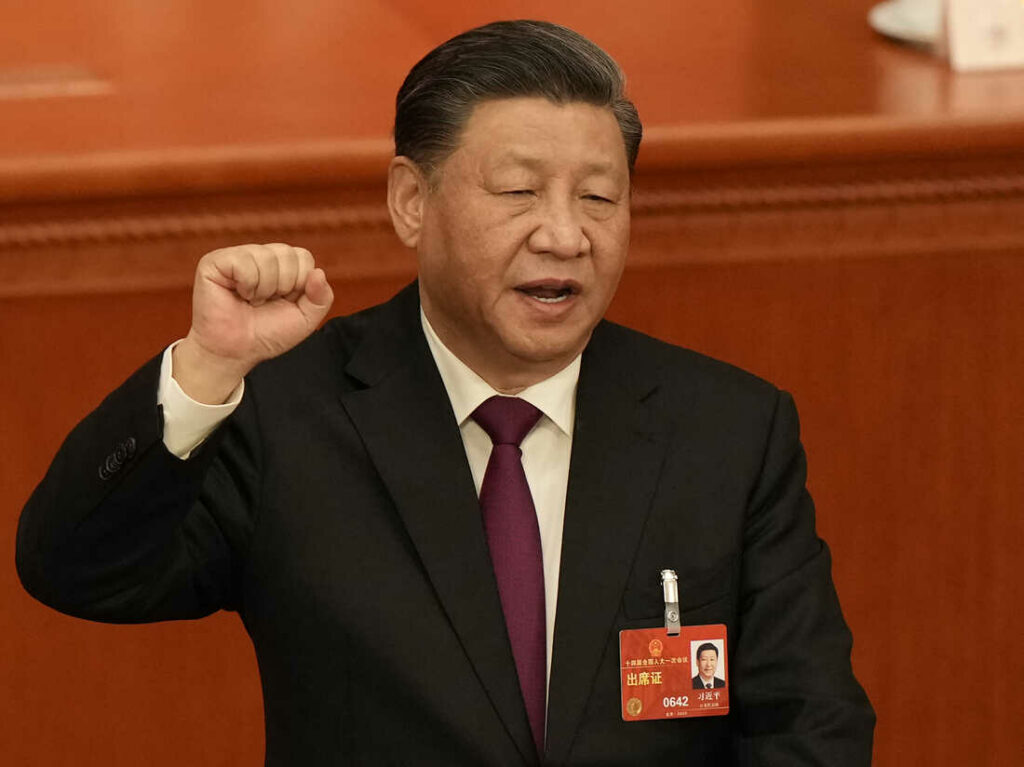

Chinese President Xi Jinping takes his oath after he is unanimously elected as President during a session of China’s National People’s Congress (NPC) at the Great Hall of the People in Beijing, Friday, March 10, 2023. AP with permission.

This is part 2 of a four-part series. Part 1 Part 3 Part 4

DECONSTRUCTING XI’S BOGUS HISTORY OF CHINA’S RISE AND ITS “SUPERIORITY”

I. Why do Chinese flee China’s “superior civilization” for the “declining West”?

To begin with, it’s often been observed that Mr. Xi rejects all Western ideas except one, Marxism. He celebrates Marx all the time. In a speech marking the two hundredth anniversary of Marx’s birth in May 2018, Xi reaffirmed that “Writing Marxism onto the flag of the Chinese Communist Party was totally correct… Unceasingly promoting the sinification and modernization of Marxism is totally correct.”[1] Yet Xi can hardly claim Marx’ support for his theory of “non-Western” modernization.” For far from rejecting “Western bourgeois values,” Marx and Engel’s vision of socialism was rooted in the Enlightenment values of science and democracy. They championed the achievement of the human rights of free speech, universal suffrage, democratic elections, habeas corpus, the right to peaceful assembly and association, freedom of the press, and public education uncensored by the state even more ardently and forcefully than the bourgeoisie itself because those victories consolidated in the course of the English, American and French revolutions were not just victories for the bourgeoisie against feudalism but also victories for the proletariat against the bourgeoisie and capitalism — and indispensable prerequisites for a future socialism. Thus:

The bourgeoisie cannot fight for his political rule, nor express this political rule in a constitutional laws without at the same time, putting weapons in the hands of the proletariat . . . Consistently, therefore, it must demand direct, universal suffrage, freedom of the press, organization, and assembly, and abolition of all discriminatory laws against particular classes of the population. . . It is therefore in the interest of the workers to support the bourgeoisie and its struggle against all reactionary elements, so long as the bourgeoisie remains, true to itself.[2]

Yet in practice the bourgeoisie often failed to remain true to itself, in which case it fell to the workers and plebians to finish the revolution for the bourgeoisie, and in the process to secure the rights that workers could eventually turn against the bourgeoisie themselves. Thus

[Had it] not been for that [British] yeomanry and for the plebeian element in the towns, the bourgeoisie alone would never have fought the matter out to the bitter end and would never have brought Charles 1 to the scaffold. In order to secure even those conquests [universal suffrage, freedom of speech and the press, the right to assemble, etcetera] of the bourgeoisie that were ripe for gathering at the time, the revolution had to be carried considerably further — exactly as in 1793 in France in 1848 in Germany.[3]

Voting with their feet

If Western values are obsolete and inappropriate for developing nations, why do China’s leaders all send their children to Western universities? Xi Jinping sent his only daughter Xi Mingze to Harvard in 2010 (which he could hardly afford on his legal salary thought to be around $20,000 a year but could easily afford because he and his whole family were multimillionaire kleptocrats long before he was installed as general secretary of the Communist Party in November 2012).[4] Reportedly, she prefers life in Boston over Beijing.[5] If the superiority of Chinese-style civilization is so obvious, why don’t Western college students flock to China to get their education instead of the other way round? And why are more and more Chinese fleeing to the “declining” West? Of the 10.5 million PRC emigrants living abroad in 2021, virtually all of them moved to Western, Eastern and other capitalist democracies (most to the U.S., E.U., South Korea, Japan, Australia, Malaysia, New Zealand, South America, in that order.)[6] Currently, 5.2 million people of Chinese descent (excluding Taiwanese) live in the United States.[7] Xi’s crackdowns have only accelerated this exodus as Chinese vote with their feet.[8] Western capitalist democracies have many problems. Yet while people scale walls or set out on flimsy rafts to migrate to Europe and the United States, no one clamors to move to China. Of its 1.4 billion people, barely a million, just 0.07%, are immigrants.[9] Right now Beijing is trying to staunch the outflow by banning courses in “preparation for emigration” at Hong Kong universites.[10] With the economic slump, Covid lockdowns and Xi’s fierce political repression, a top trending search by young Chinese on Weibo (China’s twitter equivalent) has been runxue (literally, the English verb run + the Chinese verb study) – researching how to get out of China.[11]

As of November, more than 24,000 PRC escapees have crossed the Mexican border into the United States this year. Typically, they fly to Ecuador which admits them without a visa, then make their way to Mexico. Once in the U.S. many apply for asylum and most succeed.[12] In March, the Guardian reported that disillusioned Chinese emigrants (913 in December 2022 alone), are so desperate to reach the United States that they’re undertaking the arduous and dangerous trek across the roadless, lawless and deadly Darian Gap between Columbia and Panama. The paper quotes a Mr. Xu who says that he used to identify with China’s “Little Pinks”, a group of cyber-nationalists, but in 2021, he began learning about the Great Chinese Famine and the Tiananmen Square massacre by using virtual private networks, or VPNs. “I realised [the CCP] don’t care about human rights,” Xu says. “After I leave the country [China], I have no plans to go back alive.” “I feel like this country has been deceiving us, persecuting us. I have to do something.” He points to the rash of suicides and family separations under Zero Covid, which were ignored by a state media only talking of a “tremendous victory.” “They [the Communists] would do anything to disregard ordinary people’s pain,” he says. “I don’t know much about the US, but at least it’d be better than living in China.” Another, Mr. Yin, a 55-year-old cook from Nanjing says that China’s tough pandemic rules were just one of many reasons that he wanted to escape life under the Chinese Communist Party. “I’m not afraid of them at all,” Yin says. “We would go help Taiwan fight against the CCP if China attacks Taiwan.” What kind of “superior civilization” can’t keep its own people from risking their lives to flee?[13]

Curiously, Western Maoist apologists for China such as Monthly Review’s John Bellamy Foster and Vijay Prashad trumpet Xi’s claims for poverty alleviation and “ecological civilization” but never trouble ask themselves the obvious question that Fang Zhili poses: “Why should a good society fear that people are going to run away? If you’re so good, people will be trying to get in, not out.”[14]

Voting with their wombs

Those who can’t get out face a bleak future of a decelerating economy, rising unemployment, and an aging society as young Chinese women have gone on strike, voting with their wombs against the party-state, declaring themselves the “last generation.”[15] The same government that banned women from having more than one child in 1981 is now pressuring them to become baby factories. The Party that once encouraged women to join the workforce, is now telling them that “their place is in the home, rearing children.”[16] This is not going to work for at least three reasons: First, educated women all over Asia are rebelling against patriarchal cultures, refusing to marry or have children.[17] Birth rates are plummeting and populations are shrinking in South Korea, Taiwan and Japan too. Second, since the privatizations of social services in the 1990s, the cost of raising children in China has become unaffordable for many. The old system of free public childcare and free public schools is no more. And though state schools don’t charge tuition for primary and secondary schools, school “fees” can be steep. The supply of public kindergartens is also seriously inadequate, and private ones prohibitively expensive for most. The patchwork of health insurance is expensive, coverage is minimal, and does not include children. Women also face systematic discrimination in jobs, pay, and advancement, even height. Single women suffer additional barriers. They get no state support, are ineligible for the few subsidies allocated to married mothers and are regularly denied paid maternity leave by their employers. Third, women are revolting against the lack of human rights. As one single mom said “What many women, especially single mothers, lack is not money but the protection of their rights and the respect of society.[18] That’s not likely to be forthcoming from the Xi’s CCP (the 24-member Politburo includes zero women and just 5% of the 205-member Central Committee are women).[19] Far from expanding the rights of women, Xi’s Communist Party is locking up feminists and extinguishing the last of what rights the Chinese people thought they were entitled to in their paper constitution but discovered in three years of Covid lockdowns that after all, they’re just 1.4 billion prisoners. As the anti-lockdown protesters chanted last November, “We don’t want to be slaves. We want freedom. We want rights. We want democracy. We don’t want dictators, we want to vote.”[20] China’s collapsing birth and marriage rates are expressions of the deep pessimism of young people. And Xi faces not just the women’s strike. In recent years many Chinese young people of both sexes are “lying flat” — refusing to take high pressure jobs in response to the grueling “996” work schedule (9AM-9PM, 6 days a week).[21] demanded by China’s tech companies and by regime and societal pressure to over-work and over-achieve. This has given rise to the “Four No” movement: no dating, no marriage, no home ownership, no kids.[22] In short, a vote of no confidence in bleak future Xi Jinping is engineering for his subjects.[23] In what Western democracy do young people declare themselves “the last generation” and protest in the streets against state slavery?

II. Debunking the debunker –

- We have completed in decades the industrialization process that had taken developed Western countries hundreds of years.”

Yes it certainly did take centuries of step-by-step advances in rational critical thinking and scientific advancement from the 15th-16th centuries Renaissance and beginnings of the Scientific Revolutions of Copernicus, Galileo, Brahe, Bacon, through the 17th-18th centuries Enlightenment of Newton, Kepler, Descartes, Locke, Adam Smith, Kant and others, to the James Watts, Richard Arkwrights, Thomas Newcomens, Thomas Edisons and Henry Fords of the Industrial Revolution of the 18th to 20th centuries, to lay the foundations of our modern industrial societies. But once the scientific, technical, and industrial bases of modernization had been laid in the West, the Chinese had no need to invent the wheel all over again, industrializing without capitalism and at “China speed” as Mr. Xi implies. China just “skipped over stages” by copying it wholesale from the West like Japan, South Korea, Taiwan and other countries had done before China. Trotsky gave this historical process a name: “combined and uneven development.”

China’s miracle in East Asian comparative perspective

In fact, China’s “miracle” was neither an “unprecedented feat” nor as rapid as the modernizations of its own East Asian neighbors, let alone characterized by “long-term social stability.” In Xi’s telling, China’s rise was a continuous smooth ascent from 1949 to today. In truth, China lost three decades as Mao worked and starved to death tens of millions of Chinese in his “Great Leap Forward,” then terrorized the whole population and killed another couple of million people in his crazed “Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution” such that by his death in 1976 China was worse off and further behind the West than it had been in 1949.[24] In those same decades, China’s neighbors, the “Four Tigers” (Taiwan, Hong Kong, South Korea and Singapore) brewed up the original export-oriented industrialization “East Asian Miracle” that China completely missed.[25] They were all at roughly the same socio-economic level as China in 1949 (and Korea would endure another war in 1951-53), but by the 1980s the Four Tigers were already fully modernized industrialized economies. By the 1990s they were all first-world “high income” economies whereas Communist China could not even attain lower-middle income status until 2001.[26] Furthermore, China’s neighbors also eliminated mass poverty and except for Hong Kong which was still a U.K. colony, transitioned to democracies by the 1990s to boot. In short, they fully accomplished their East Asian Miracle modernizations while China dragged itself through three decades in Maoism-in-poverty under the Party’s then “correct policies.”

What’s more, the former copycats South Korea, Taiwan, Singapore went on to become mighty tech innovators in their own right while China’s state sector and its SOEs remain incapable of significant innovation such that Mr. Xi still finds himself in the humiliating position of having to beg, coerce, threaten or steal – mostly steal — regular infusions of leading-edge science and technology from the declining West to keep his economy advancing.[27]

- “Chinese socialism not Western capitalism modernized China’s economy”

Xi’s claim that Chinese-style modernization “abandoned the old path of capital-centered Western modernization” and is “not dependent upon others” is perhaps the most obviously counterfactual of his four theses. This argument is part of retro-Maoist Xi’s effort to drive capitalism out of China, recenter and promote the state economy, airbrush Deng and his market reform era out of Chinese history books and museums and rewrite history to portray China’s rise as due solely to the brilliant and glorious Chinese Communist Party and its SOEs, not Western capitalists and their science and technology.[28]

Manifestly, China’s rise has been wholly dependent upon Western capitalism from the outset in 1978 down to today. China’s industrial modernization began with Deng Xiaoping’s marriage of Western capital to Chinese labor in his new export-processing Special Economic Zones (SEZs) set up from 1978. He invited Western and investors and companies to bring in their capital, their modern technology, new industries, and expert managerial and production knowhow in return for granting them the right to dramatically cut their cost of production by super-exploiting China’s unfree ultra-cheap labor with few environmental restrictions. He also gave them access to the world’s biggest untapped market, an irresistible incentive. Initially, most FDI (Foreign Direct Investment) was concentrated in archipelago of 14 Special Economic Zones (SEZs) along China’s east coast but in the 1990s dozens of new iterations were added.[29] The SEZs were fenced off from the rest of the economy. In some cases, as with Foxconn’s factories, they are rigidly militarized. Indeed, since 2010 Foxconn’s factory dormitories have also been conveniently fitted with anti-suicide nets to prevent China’s blissfully happy “common prosperity”- enjoying workers from jumping off the roofs to their deaths.[30] SEZs grant tax concessions and duty-free imports and exports. The government’s contribution to this project was to provide labor and build the necessary infrastructure: land, ports, roads, rails, water and power, and telecoms.

The new SEZs comprised a capitalist economy within the framework of the old Stalinist state-owned centrally planned economy. The government still owns all the land and natural resources and most of the economy including the commanding heights: large-scale mining and manufacturing, heavy industry, metallurgy, shipping, energy generation, petroleum and petrochemicals, heavy construction and equipment, atomic energy, aerospace, telecommunications and internet, vehicles (some in partnership with foreign companies), aircraft manufacture (in partnership with Boeing and Airbus), airlines, railways, most pharmaceuticals and biotechnology, banking, military production, as well as the media, schools and universities. The state-owned industrial economy has always been far larger than the private and joint-venture economy. Even so, according to the World Bank, by the 2010s SEZs accounted for 22% of China’s GDP, 45% of total national foreign direct investment, and 60% of exports and had created tens of millions of new jobs.[31] Whereas, in 1978, virtually everyone worked for the state, by the 2010s more than 80% of the urban labor force were working in private businesses or were self-employed.[32]

In the first decades of reform and opening, all the Foreign Invested Enterprises (FIEs) were run by foreign engineers and executives. But as the famously industrious, education-focused, quick-learning and entrepreneurial Chinese learned how to operate modern technology and factories and China educated its own engineers and technicians, they staffed more and more of the engineering and managerial positions and Chinese companies supplied more and more of the physical inputs to replace imports.[33] By the 2000s and 2010s developing domestic private competitors were clawing back shares of the domestic market from foreign manufacturing and retail as well as creating entirely new high-tech electric vehicle and e-commerce industries. Google quit China in 2010 over tech theft, leaving the market to Baidu and other Chinese search engines. The state-backed Didi Chuxing ride-hailing service drove out Uber in 2016. KFC and MacDonalds were driven out by Chinese competitors the same year. Panasonic abandoned TV and solar panel production in China do to “fierce competition” from domestic producers, and so on.[34] By the 2010s Huawei had become the world’s biggest telecom company and homegrown private tech companies like Alibaba, Ant Financial, Baidu, Tencent, Bytedance, Warren Buffet-backed BYD Company Ltd. (the world’s largest electric vehicle manufacturer), and CATL (Contemporary Amperex Technology Co., the world’s largest EV battery maker) were leading the economy. In 2022 Bytedance’s TikTok became an international sensation and the top downloaded app in the United States. Thus pace Mr. Xi’s fable, Chinese-style modernization has been indisputably powered by capital accumulation, by private investors and corporations both foreign and domestic from 1978 to today. Indeed, ironically, while Xi has campaigned to reassert Party control over the economy and promote the state-owned SOEs against the private sector, the government’s decades-long failure to kickstart indigenous innovation in state-owned industries like microchips, aviation, pharmaceuticals, among others, despite spending hundreds of billions of dollars such efforts since the 1990s, leaves China’s economy’s more dependent on Western and Chinese capitalists than ever—a major problem for Xi’s goal of state-sector economic supremacy.[35]

The Communist Party’s unique “innovations in the theory of world modernization”

Yet Xi is correct that China’s modernization is unique compared to India and the Four Tigers — just not in the way he claims.What the Communist Party uniquely contributed was its all-powerful and well-organized police state. As I explained elsewhere, when globalization took off in the 1980s, made possible by revolutionary developments in technology and manufacturing processes such as computerization, the internet, and modularization of production that permitted sourcing components from several (and often competing) nations,

What gave China the advantage as an export platform over, say, India which had at least as many millions of hungry jobless workers, was that China had a highly organized and effective developmental police state that could not only furnish labor and control labor costs, but could also clear land and concentrate resources to build the industrial parks and infrastructure (power plants, ports, roads, railways, telecommunications, and so on) to get them up and running, and could build new universities to train engineers.[36]

Apartheid with Communist Party characteristics

With respect to the labor force, the Communist Party’s innovation was to supply hundreds of millions of union-free, EPA free, OSHA free, NIOSH-free, police-state enforced, semi-slave migrant workers to be exploited by Western capitalists at the world’s lowest cost, virtually industrial revolution-era wages, what employers termed the “China Price.”[37] In fact, the Communist Party — self-proclaimed representative of the proletariat — created an entire apartheid class of ex-farm migrant proletarians, nearly 300,000 million strong, to supply the SEZs, urban and infrastructure construction, supply urban domestics, delivery services, etc. with pliant super-exploitable workers. In contrast to South African apartheid, this class of Chinese workers is not distinguished by racial identity but solely by their lack of an urban hukou or legal residence permit. This system was established in the early 1950s when the Party sought to prevent mass migration from the country to the cities by assigning every Chinese a hukou based on where they were born. Such assignments were permanent and were inherited by their children. Access to housing, childcare, schooling, medical care, rations, and subsidies were all determined by one’s hukou. By denying those new migrant workers an urban hukou, they could not legally buy an urban residence, and so have been condemned to live for forty years on the margins, in peri-urban slums, in company dormitories (as at Foxconn), on the street, etc, subject to being expelled and sent back to their rural homes at the whim of local officials. As illegal migrants in their own country, they have no legal right to send their children to urban public schools, no legal entitlement to urban medical or other social services, no legal entitlement to state provided minimum subsistence payments (the dibao), disability insurance, state-provided pensions and death benefits. Some of these restraints have been relaxed by local officials in second- and third-tier cities. But the formal national legal structure remains in place and is vigorously enforced in top-tier cities like Beijing where the government is determined to cap the urban populations, by force when necessary.[38]

By comparison, India suffers from numerous disadvantages in its bid to become an export powerhouse. High on this list is its political system— democracy. Prime Minister Modi complains that democracy is a barrier to development because he can’t get his parliament to overhaul labor laws that favor workers. Nor can he get rid of land laws that prevent the converting of farmland to factory sites. India’s workers strike when they feel aggrieved, as they did when Modi attempted to make it easier to fire them. By contrast, independent trade unions are illegal in China and the right to strike was deleted from the national constitution in 1982. Nonetheless, in recent years there have been more than a thousand industrial strikes per year in the country, but they’re all illegal and labor organizers are routinely locked up or worse.[39] China’s police-state advantage is again on display today as companies under pressure to shift their manufacturing bases out of China try to relocate to places like India. Indian workers are not keen on working 12-hour days, females don’t want to work night shifts, and employers can’t just marshal 100,000 Indian workers to work all night to meet some Apple deadline like Foxconn factories do in China. Moreover, the companies cannot always count on the police to tip the balance of class struggle in their favor. In one recent case, workers struck for higher wages, better labor protection and when those were not forthcoming, trashed a Taiwanese Apple subcontractor’s factory “causing millions of dollars in losses to the Taiwanese company and forcing it to shut the plant.”[40]

Primitive accumulation with Communist Party characteristics

With respect to land and natural resources, China’s innovation in modernization has been the government’s right and power to clear land and mobilize water and other natural resources at will, whenever and wherever it wished to build new dams, ports, industrial parks, roads, railways, airports, or new cities. Since the government owns all the land and natural resources, and controls the police and courts, it doesn’t have to bother with public hearings, environmental impact statements or legislatures. Since the 1990s, it has summarily evicted hundreds of millions of farmers from their land and tens of millions of urban residents from their apartments and houses, with or without compensation.[41] That’s how it built thousands of kilometers of new highways and high-speed railways across the country since 2008. This was only possible because the central government could mobilize and concentrate funds and resources on massive infrastructure projects like those and could expropriate farmers and urban residents by fiat. No other contemporary modernizing government in the world has the power to carry out such wrenching transformations.[42]

By comparison, in India in 2007, Tata Motors won approval from a local government to build an auto factory in the Ganges delta in India’s West Bengal. But while the factory was under construction, protesting peasants elected a new government that promised to return the farmland to them, which it did in 2017. This is a common problem for industrialists in India’s still mostly agrarian but democratic country.[43] Recall that in England, even with the state on their side, it still took centuries of class struggle for the new capitalist landlords to complete the process of “primitive accumulation,” to expropriate peasant freeholders, turn them into wage laborers, and convert their farms into sheepfolds.

In short, it’s difficult to overstate the importance of China’s police-state advantage for speeding industrial modernization. Police-state enforced ultra-cheap labor + state ownership of all land and resources + the Communist Party’s monopoly of political power – those were the Party’s “major innovations in the theory of modernization” that distinguished China’s industrial modernization from those of Taiwan, South Korea etc.

- “Chinese modernization is a modernization of common prosperity for all people, not just for a few.”

Indeed. This will come as news to those 300 million impoverished migrant workers denied urban hukous and public schools, who struggle to scrape together money to build and staff their own shanty-town schools — only to see the government that professes its “love and serve the people,” send in demolition crews to demolish them along with their makeshift housing, to kick what Communist officials term the “low-end population” (diduan renkou) out of its first tier cities like Beijing and Shanghai.[44] This will also be news to the thirty million SOE workers who were laid off in the late 1990s and, once out the door, were cut off from company-provided healthcare, pensions and other benefits, to become precarious workers like the ex-farm migrants, or retire in poverty struggling to survive on the state’s stingy dibao (the dole).[45]

Worse than capitalism

Far from “resolutely preventing polarization,” Communist Party-style modernization has constructed one of the most economically polarized societies in the world, a society characterized by a massively higher rate of poverty, and more extremes of wealth and poverty than found in the world’s industrial capitalist democracies. At the top, the Hunrun Global Rich List reported in 2019 that China had more billionaires than the U.S. and India combined.[46] Ninety-nine percent of them are Communist Party members. In 2002 the New York Times reported that China’s National People’s Congress – the “congress of crony capitalists” – possessed a collective wealth of hundreds of billions of dollars.[47] A Bloomberg exposé of CCP aristocratic “princelings” in 2012 revealed that Xi Jinping and his close relations had already amassed a fortune in minerals, real estate and telecoms worth at least 376 million dollars even before he was anointed party secretary in 2012. The New York Times calculated that as Xi took office in 2012, outgoing Premier Wen Jiabao (whose annual salary was about $15,000) was worth at least $2.7 billion when he retired, all of it secreted under the names of his close relatives and associates. Even his retired school-teacher mom was worth $190 million.[48]

At the bottom are the proletariat and precariat, the apartheid subclass of migrant proletarian workers, and the farmers. After seven decades of “socialist” development, China still has many times more extremely impoverished people than either its East Asian industrialized neighbors or the capitalist economies of West Europe and the United States. In terms of the GINI coefficient, a commonly used metric of inequality (On a scale 0 to 100, 0 corresponds with perfect equality where everyone has the same income, and 100 corresponds with perfect inequality, where one person has all the income and everyone else has no income), according to the World Bank China’s current GINI coefficient is 38.2, just 3.3 points more equal than capitalist United States at 41.5, but significantly more unequal than capitalist South Korea at 31.4, Japan at 32.9, and Taiwan at 33.6. In Europe, Germany’s GINI is 31.7, France is 32.4, and even Thatcherite England at 35.1 is more equal than China, let alone Norway and Finland both 27.7 or Sweden and Netherlands, both 29.5.[49]

Living the Big Lie

Yet the GINI coefficient vastly underestimates inequality in China because its estimates are based on reported incomes whereas, as I’ve discussed elsewhere,[50] in China official salaries are pocket change. Uniquely, compared to other modes of production like feudalism or capitalism, China’s CCP ruling class have become filthy rich, collectively perhaps the richest ruling class in the world, but they’re obliged to hide their wealth because it’s all ill-gotten, illegal. Which means that Communist Party members have to live the Big Lie, pretend to be “proletarian” revolutionaries like their “plain living and hard struggling” Maoist forebears of the 1930s and 40s while using their Party cards to tap the state’s ATMs. As China got rich, rivers of money flowed into government coffers from the profits of SOEs, foreign trade, taxes and so on and China accumulated the world’s largest foreign exchange hoard, nearly four trillion dollars in 2015. Yet individual CCP members have no legal title to any of that treasure. The only way they could take “their share” of the party-state’s wealth was to steal it by one means or another, and hide it: Loot the SOEs, the banks, pension funds, etc., list it in their wives’ and children’s names, stash it in secret offshore accounts in Panama or the Cayman Islands, smuggle it out through Hong Kong banks to buy properties in Vancouver or Los Angeles or New York, and so on.[51]

Millionaire and billionaire Chinese Communist Party officials, including Xi Jinping’s close relatives, accounted for the largest single national group of offshore secret account holders revealed in the Panama Papers.[52] As Deng Xiaoping said, “some have to get rich first,” so he saw to it that his own children were among the first at the trough.[53] If the secret wealth of China’s tens of millions of filthy rich Communist Party members were included, China’s GINI co-efficient score would be off the charts.

The fraud of “poverty eradication”

Xi claims his Party’s policies have “eradicated absolute poverty.” This claim is zealously promoted by Western Maoists who don’t trouble to look at the evidence for this claim.[54] What Xi has virtually eradicated is any public mention of poverty. In March, the Cyberspace Administration, the country’s internet regulator, announced that it would crack down on anyone who publishes videos or posts that portray “sadness, incite polarization, or create harmful information that damages the image of the Party.” It bans sad videos of old people, disabled people, and children.[55] When Hu Chenfeng, an underground journalist posted a heartbreaking video in which an elderly retired widow in Chengdu showed him what groceries she could buy with her monthly pension of 100 yuan or $14.50 (basically just rice), Hu’s video was censored and his accounts suspended.[56] Instead of eradicating poverty, Xi is manufacturing poverty as his crackdowns on the private businesses are throwing millions of workers, young and old, out of work. Youth unemployment is rising so fast that in August the embarrassed government stopped reporting youth unemployment statistics. Xi’s advice to China’s jobless futureless youth: “Go to the countryside and ‘eat bitterness’ like I did in the Cultural Revolution.”[57]

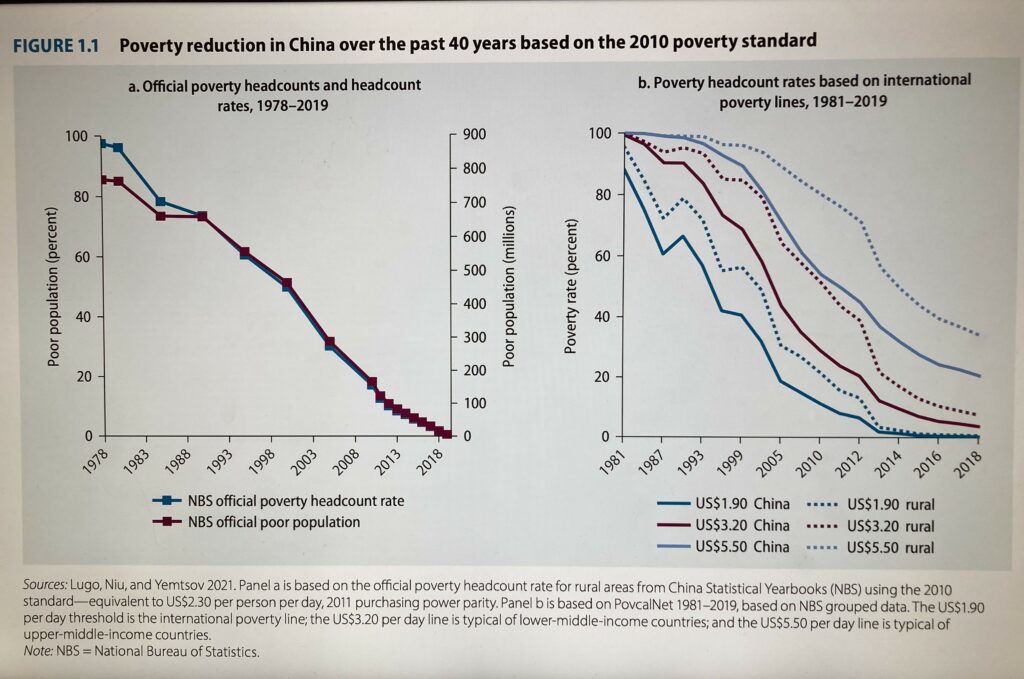

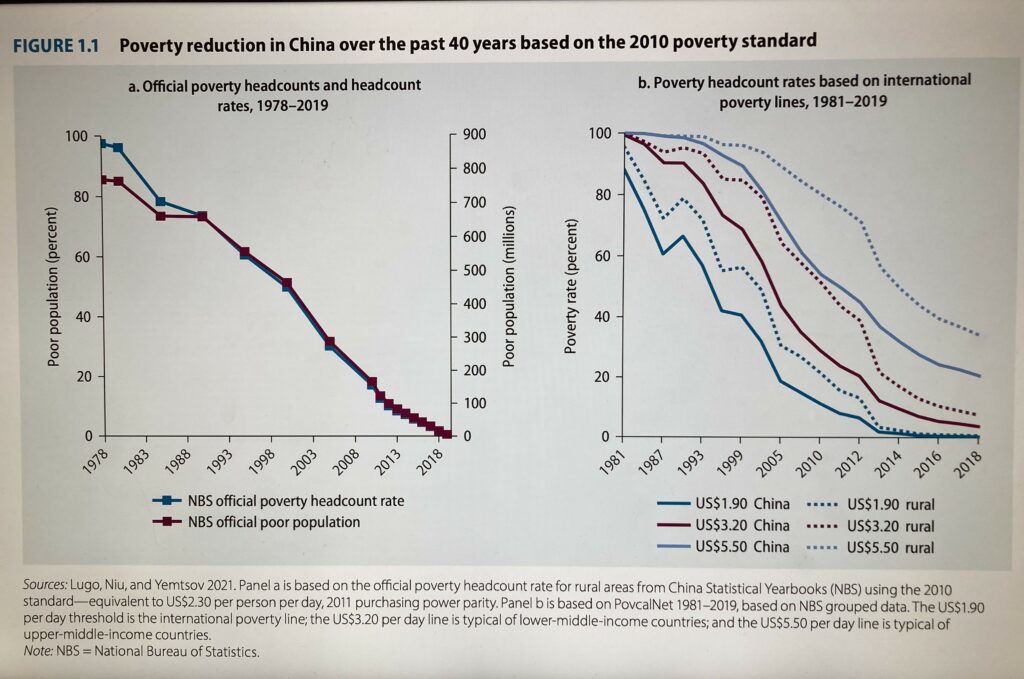

To make its claim that absolute poverty has been eradicated, China’s National Bureau of Statistics (NBS) uses the World Bank’s “extreme poverty” line of $1.90 per day (adjusted for inflation, the equivalent to $2.30 per day in 2011 Purchasing Power Parity) to count those in poverty (Figure 1 below, left panel).[58] But that number is highly misleading in respect of industrialized, urbanized, and comparatively wealthy China today. The World Bank says a threshold of $1.90 a day is appropriate for countries with annual per capita incomes of less than $1,000 or so, such as Ethiopia or China in the 1970s. For lower-middle-income countries such as India with per capita incomes between $1,000 and about $4,000, it says the poverty line should be $3.20 a day. For upper-middle-income countries like China, it says the poverty line should be $5.50 a day.[59] Using the Bank’s classification of US$1.90($2.30) per day, China’s poverty zeros out by 2018 (Figure 1, right panel, dark blue line) as Xi claims. But using the classification of $5.50 per day ($167 per month), the graph shows that about 20% of China’s 1.4 billion, 280 million people, were living in poverty in 2018 (Figure 1, right panel, light blue line). In May 2020 Premier Li Keqiang stated that “[t]he average per-capita income in China is RMB30,000 (US$4,193), but there are over 600 million people [43+% of the population] whose monthly income is barely RMB1,000 (US$140), not enough to rent a room in Chinese cities.”[60] In other words, after seven decades of “socialist modernization,” somewhere between 20% and 43% of China’s population still live in “extreme poverty.” By comparison, in countries that suffered the exigencies of capitalist modernization such as Taiwan, this figure is just 1.5%, in South Korea 15.1%, in Japan, 16.1%, in Hong Kong 19.9%, in France 13.6%, in Germany, 14.8%, in Thatcherite UK 18.6%. Even in the notoriously unequal United States, the figure is just 11.6%.[61]

Table 1. China National Income and Consumption Expenditures In 2021

|

Urban per capita average wage/salary: Y28,481

Urban per capita expenditures for living (cost of living): Y30,307

Rural per capita average wage/salary: Y18,931

Rural per capita expenditures for living (cost of living): Y15,916

|

China’s 600+ million poor are comprised of the hundreds of millions of rural poor living in villages and farms, most of whom depend on remittances sent to them by their children working in the cities, laid-off SOE workers surviving on the dibao, and many of the 300 million apartheid underclass migrant workers who eke out a marginal existence as semi-legal workers in the cities.

Xinhua recently ran a headline entitled “U.S. mired in wave of strikes fueled by inequality.”[62] That’s true. But in Xi’s “whole-people democracy” people can’t even legally strike, protest, or even talk about poverty in public or on social media, let alone vote for a different party. What kind of democracy is that?

- “Chinese-style modernization is a modernization in which man and nature live in harmony.”

This thesis is cruel irony to the thousands of Chinese wasting away and dying in China’s hundreds of “cancer villages” or indeed to all Chinese.[63] Large swathes of China would count as EPA toxic waste dumps, more than any other large country in the world. 70% of its rivers and lakes are unsafe for human use of any kind, according to the government.[64] 80% of China’s ground water aquifers are officially “unfit for human consumption” because of industrial contamination.”[65] Not one city in “modern” China can provide potable tap water. Decades of wanton pollution of rivers, lakes, reservoirs, and aquifers with agricultural chemicals, industrial dumping, untreated sewage dumping, and use of industrial wastewater to irrigate farmlands has degraded much of China’s farmland, contaminated food supplies, and damaged the health of millions. Farm soils are contaminated with all manner of heavy metals including cadmium, mercury, chromium, lead, arsenic, and other chemicals. Officially at least 20% of China’s farmland is “seriously polluted” with heavy metals including cadmium, nickel, arsenic mercury, lead and other chemicals. Much of the rest is extensively contaminated.[66] In 2013, the Ministry of Lands reported that 2% of China’s farmland — an area the size of Belgium — was too polluted to grow crops. Efforts to clean up water and soil pollution have all been conspicuous failures.[67] Food contamination and food poisoning are never-ending nightmares in China, compounded by deliberate food adulteration for profit like the serial contaminated baby formula scandals since 2008 that continue to this day. That’s why Chinese parents scour grocery shelves, the internet, and implore their overseas relations and friends to bring or ship them safe foods from the “declining West.”[68] China has had so many drug and vaccine scandals that many Chinese refused to take the government’s Covid vaccines. Government regulation is an abject failure across the board.[69] Unsurprisingly, cancer is epidemic in China, “rising rapidly” while cancer indices are falling in the (declining) West.[70] Lung cancer is the leading cause of death in industrialized northern China, indeed, the top killer of both men and women in both urban and rural China.[71] After lung cancer, gastrointestinal cancers, closely associated with soil and water pollution, are leading causes of death in rural China.[72] Quoting Xi Jinping who said “If we do not do a good job in food safety, and continue to mishandle the issue, then people will ask whether our party is fit to rule China,” Professor Yanzhong Huang who has written an entire book on the pollution-induced health crisis in China, recently wrote:

Growing up in a village by the Yangtze River, I may have dreamed of having a bowl of rice every day, but I did not have to worry about the safety of my food. Now, with hundreds of millions of people being “lifted out of poverty,” their defining anxiety has shifted from food security to food safety. It is hard to imagine that China can regain its former greatness while its people lack uncontaminated soils on which to farm.”[73]

Xi is correct in saying that “under the capitalist modernization model, capital’s endless pursuit of profits [and] unrestrained demand for natural resources inevitably leads to ecological crisis.” Yet today it is ironically “socialist” China’s disproportionately huge CO2 emissions that are leading the world to climate collapse while its relentlessly growing resource consumption is plundering and annihilating ecologies around the world. China’s carbon emissions are nearly triple those of the United States with a GDP just two-thirds as large. Since 2019 China’s emissions have exceeded those of all developed countries combined and presently account for 33 per cent of total global emissions.[74]

It’s often said in China’s defense that while China’s current annual emissions may lead the world by far, historically, the United States has contributed the most CO2 to the atmosphere. That’s true. But according to NOAA, on current trends China’s cumulative emissions will exceed those of United States in just 15 years.[75] Even in per capita terms, China’s CO2 emissions “now exceed the average in the advanced economies” according to the IEA.[76]

“Socialist” China is also “outpacing the rest of the world in natural resource use” according to the United Nations. In a 2013 report, UNEP concluded that “China’s growing affluence has made it the world’s largest consumer of primary materials (such as construction minerals, metal ores, fossil fuels and biomass), with domestic material consumption levels four times that of the USA.”[77] In per capita terms, PRC Chinese still consume a tiny fraction, roughly a fifteenth as much natural resources, as do Americans. As the Sierra Club has written: “With less than 5 percent of world population, the U.S. uses one-third of the world’s paper, a quarter of the world’s oil, 23 percent of the coal, 27 percent of the aluminum, and 19 percent of the copper. Our per capita use of energy, metals, minerals, forest products, fish, grains, meat, and even freshwater dwarfs that of people living in the developing world.”[78] But, again, the planet does not care about per capita consumption, only total consumption. And in this regard, without in the least excusing Western capitalism’s obscene per capita levels of resource consumption[79] still, as I’ve written elsewhere:

China’s voracious consumption of natural resources is out of all proportion to any rational economic need, and flagrantly disregards local and international environmental regulations and laws. Conservationists liken China to “a giant vacuum cleaner of the natural world.”

China is the leading driver of global deforestation, consuming more lumber than the rest of the world put together. It is also the largest importer of illegally logged lumber. While protecting its own forests, China is leveling forests from Siberia to South America to satisfy the voracious appetite of its construction companies, papermakers, and flooring and furniture manufacturers. A recent headline in the South China Morning Post read: “Chinese consumers’ crazy rich demand for rosewood propels drive toward its extinction.”

Chinese loggers are also destroying the habitats of Siberian tigers, Amur leopards, Indonesian orangutans, and dozens of rare birds, driving an untold number of species to the edge of extinction. Just as there’s no market in China for ecologically certified lumber, neither is there a market for ecologically certified palm oil, beef, seafood, or agricultural products. . . It’s fishing fleets plunder the world’s oceans, depriving North Koreans, coastal Africans and Latin Americans of fishing jobs.

China is the largest consumer by far of illegally poached wildlife— elephants, lions, tigers, rhinos, sharks, pangolins, and dozens of exotic bird species—for its booming trade in traditional medicine. With state media fully occupied trumpeting patriotic propaganda about “Amazing China,” its citizens have no idea that their country leads the world in CO2 emissions, nor that their country is almost single-handedly responsible for the industrial-scale slaughter of exotic fauna and flora at the center of the “Sixth Extinction.”[80]

Xi Jinping is emphatically correct to say that “We will not be able to follow the old path of the United States and Europe in building a modern country, and a few more earths are not enough for the Chinese to consume. The old way, to consume resources, to pollute the environment, cannot be sustained!” But why then, is his Chinese-style civilization consuming more natural resources per unit of GDP than the U.S. or Europe? Why are China’s fishing fleets plundering the world’s oceans, devastating fisheries (and destroying the livelihoods of fishermen) in Africa, South America, the South Pacific and Indian oceans?[81] Why is China the leading driver of exotic species extinction?[82] Why does it lead the world in dumping toxic pollution in lakes rivers and farmland? And why is “socialist” China leading the world to climate collapse?[83]

The fact is, neither Western capitalism nor China’s hybrid communist-capitalism are sustainable. They’re both suicidally unsustainable. Ecologically speaking, the fundamental contradiction in Xi’s “Chinese-style modernization” is his assumption that he can decouple resource consumption and emissions from growth in order to maintain that 6%+ growth rate to overtake the United States and become the world’s top superpower. As I argued in my book and follow-up article, such decoupling is as impossible in Communist China as in the capitalist West. Xi can, as he promised the world in his 2020 televised speech to the United Nations, either “transition to green and low-carbon development . . [and] take the minimum steps to protect the Earth, our shared homeland,” or he can pursue his 6%+ growth rate. He can’t do both — and neither can we. Infinite growth on a finite planet is the road to collective ecological suicide.[84]

Notes:

[1] Christian Shepherd, “No regrets: Xi says Marxism still ‘totally correct’ for China,” Reuters, May 4, 2018, https://www.reuters.com/article/cnews-us-germany-marx-china-idCAKBN1I50ET-OCATP.

[2] The Prussian military question and the German Workers Party, January-February 1865, MEW 16,87, Hal Draper, Karl Marx Theory of Revolution (New York: Monthly Review Press, 1978), Vol. II, 282 (emphasis in original), also 273-74.

[3] Socialism Utopian and Scientific, in Marx and Engels: Selected Works, 3, 105, in Draper, op cit., 275.

[4] Bloomberg, “Xi Jinping millionaire relations reveal elite Chinese fortunes,” June 29, 2012, https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2012-06-29/xi-jinping-millionaire-relations-reveal-fortunes-of-elite?sref=4KuSK5Q1. https://www.quora.com/If-Xi-Jinping-earns-less-than-100-000-USD-a-year-then-who-pays-for-his-daughters-Harvard-education. A question to Quora in September 2022, “If Xi Jinping earns less than $100,000 then who pays for his daughter’s Harvard education?” returned this answer from a Mr. Lan Yanchiu, a teacher in China: “Easy: I pay for it. Just like it is me who pays for Xi’s and his extensive family’s Shanghai and Hong Kong assets and properties, Canada and Cayman Islands companies, moreover it is me who pays for the personal wealth of each of the billionaire members of the National People’s Congress and of the Politburo. This money disappears precisely from my pocket and other Chinese citizens’ pocket and re-appears in their pocket. This is “communism with special Chinese characteristics”: the principle that “in communism there is no private property” is understood by the Party in the way that “you might think you own things, but we have the right to take anything from you at any time we wish.” https://www.quora.com/If-Xi-Jinping-earns-less-than-100-000-USD-a-year-then-who-pays-for-his-daughters-Harvard-education. Lan’s response has been subsequently deleted.

[5] “Xi Jinping’s daughter Xi Mingze living in America, reveals US Senator Hartzler,” Economic Times, February 21, 2022, https://economictimes.indiatimes.com/news/international/world-news/xi-jinpings-daughter-xi-mingze-living-in-america-reveals-us-senator-hartzler/articleshow/89728856.cms?utm_source=contentofinterest&utm_medium=text&utm_campaign=cppst.

[6] “Immigrant population by country of origin and destination, mid-2020. Estimates,” Migration Policy Institute, 2023, https://www.migrationpolicy.org/programs/data-hub/charts/immigrant-and-emigrant-populations-country-origin-and-destination?width=1000&height=850&iframe=true. See also, Heidi Østbø Haugen and Tabitha Speelman, “China’s rapid development has transformed its migration trends,” Migration Policy Institute, January 28, 2022, https://www.migrationpolicy.org/article/china-development-transformed-migration.

[7] U.S. Census Bureau,

https://www.commerce.gov/news/blog/2023/05/us-census-bureau-releases-key-stats-honor-2023-asian-american-native-hawaiian-and#:~:text=5.2%20million,and%20Japanese%20(1.6%20million).

[8] “She was supposed to be China’s Future. After ‘Zero Covid,’ she wants to leave,” interview by Lulu Garcia-Navarro, New York Times, December 15, 2022, https://www.nytimes.com/2022/12/15/opinion/china-zero-covid-chinese-dream.html?smid=nytcore-ios-share&referringSource=articleShare.

[9] “China needs foreign workers. So why won’t it embrace immigration?” Economist, May 4, 2023, https://www.economist.com/china/2023/05/04/china-needs-foreign-workers-so-why-wont-it-embrace-immigration; Haugen and Speelman, op cit.

[10] Reuters, “China ‘banning thousands of citizens and foreigners from leaving country,” Guardian, May 2, 2023, https://www.theguardian.com/world/2023/may/02/china-barring-thousands-of-citizens-and-foreigners-from-leaving-country; Chan Ho-him and Primrose Riodan, “Hong Kong political elite pressed to give up western passports,” Financial Times, March 5, 2023, https://tinyurl.com/27atn4w8; Sammy Heung, “’Preparation for emigration’ courses under fire as lawmakers call for inclusion of national security clauses in subsidy conditions,” South China Morning Post, February 15, 2023, https://tinyurl.com/3bnvn45r.

[11] Li Yuan, “‘The last generation’: the disillusionment of young Chinese,” New York Times, March 24, 2022, https://www.nytimes.com/2022/05/24/business/china-covid-zero.html.

[12] Eileen Sullivan, “Chinese join migrant crush on U.S. border,” New York Times, November 25, 2023.

[13] “Growing numbers of Chinese citizens set their sights on the US – via the deadly Darian Gap,” Guardian, March 8, 2023, https://www.theguardian.com/world/2023/mar/09/growing-numbers-of-chinese-citizens-set-their-sights-on-the-us-via-the-deadly-darien-gap.

[14] Eg. John Bellamy Foster et al., “Why is the great project of Ecological Civilization specific to China?” Monthly Review, October 1, 2022, https://mronline.org/2022/10/01/why-is-the-great-project-of-ecological-civilization-specific-to-china/; Vijay Prashad, “China eradicates absolute poverty while billionaires go for a joyride in space: the Thirty-First Newsletter (2021),” Monthly Review, August 6, 2021, https://mronline.org/2021/08/06/china-eradicates-absolute-poverty-while-billionaires-go-for-a-joyride-to-space-the-thirty-first-newsletter-2021/.

[15] Li Yuan, “Last generation,” op cit.

[16] Stevenson, “China’s male leaders signal” op cit.

[17] Eg. Hawon Jung, “Women in South Korea are on strike against being ‘baby-making machines,’” New York Times, January 26, 2023.

[18] Nicole Hong and Zixu Wang, public is wary of trying to push for baby boom,” New York Times, February 26, 2023. Barclay Bram, “The last generation: why China’s youth are deciding against having children,” Asia Society Policy Institute, January 23, 2023, https://asiasociety.org/policy-institute/last-generation-why-chinas-youth-are-deciding-against-having-children.

[19] “It’s a man’s world. No more women leaders in China’s Communist Party,” France 24, October 24, 2022, https://www.france24.com/en/live-news/20221024-it-s-a-man-s-world-no-more-women-leaders-in-china-s-communist-party.

[20] Gan and Wang, op cit.

[21] “What is China’s 996 work culture that is polarizing its Silicon valleys,” South China Morning Post, June 9, 2021, https://www.scmp.com/tech/tech-trends/article/3136510/what-996-gruelling-work-culture-polarising-chinas-silicon-valley. Li Yuan, “China’s young people can’t find jobs. Xi Jinping says to ‘eat bitterness,’” New York Times, June 2, 2023.

[22] Jeff Pao, “Youths’ desperate ‘four no’ attitude worries China,” Asia Times, July 13, 2023, https://asiatimes.com/2023/07/youths-desperate-four-no-attitude-worries-china/.

[23] Nicolas Eberstadt, “China’s collapsing birth and marriage rates reflect a people’s deep pessimism, Washington Post, February 28, 2023; Fay Yiying and Chen Jiangyi, “After 3 years of Covid, China’s Gen-Z are mourning their lost future,” Sixth Tone, December 6, 2022, https://tinyurl.com/4cwe2mbv.

[24] Summarizing the economic achievements of the Mao era, historian John Fitzgerald writes: “Before the start of China’s reforms, 800 million people were living below the poverty line, basically the entire population give or take a few million senior party, cadres and technical expert living in a relative comfort. When the Communists seized power 30 years earlier, there had been roughly 400,000,000 people living below the poverty line. Again, that was the entire population of the country at that time. Over the intervening period of Maoist rule, the number of people living below the poverty line doubled to 800, million.” Cadre Country (Sydney: UNSW Press, 2022), 56.

[25] World Bank, “The East Asian Miracle (World Bank/Oxford University Press, 1993), https://documents.worldbank.org/en/publication/documents-reports/documentdetail/975081468244550798/main-report; Umesh C. Gulati, “The foundations of rapid economic growth: the case of the four tigers,” The American Journal of Economics and Sociology, Vol. 51, No. 2 (Apr., 1992), 161-172, https://www.jstor.org/stable/3487387.

[26] According to the criteria of national income established by the World Bank, China became a lower-middle-income country in 2001 and an upper-middle-income country in 2010, https://www.worldbank.org/en/country/china/overview.

[27] Finbarr Berminghan, “Beijing envoy warns Dutch of retaliation for chip curbs: ‘China won’t just swallow this,’” South China Morning Post, March 22, 2023, https://www.scmp.com/news/china/article/3214361/china-wont-just-swallow-beijing-envoy-warns-dutch-retaliation-chip-curbs. As James McGregor, author of a history of China’s innovation drive “writes, “while China’s scientists, prodded by the state, are making gains, significant discoveries and inventions are still few and far between given the enormous sums of money spent and China’s impressive and fast-growing talent pool.” “China’s drive for ‘indigenous innovation’—a web of industrial policies,” APCO, 2010, 4,

https://www.uschamber.com/sites/default/files/documents/files/100728chinareport_0_0.pdf; Scott L. Montgomery, “Why China may never be the world leader in science,” Global Policy Journal, March 21,2023, https://www.globalpolicyjournal.com/blog/12/09/2022/why-china-may-never-be-world-leader-science. Zhang Jun, “The Western illusion of Chinese innovation,” Project Syndicate, July 30, 2018: https://www.project-syndicate.org/commentary/myth-of-chinese-innovation-capacity-by-zhang-jun-2018-07.

[28] “Full text of the Chinese Communist Party’s new resolution on history,” Nikei Asia, November 19, 2021, https://asia.nikkei.com/Politics/Full-text-of-the-Chinese-Communist-Party-s-new-resolution-on-history; “Xi Jinping is rewriting history to justify his rule for years to come,” Economist, November 6, 2021; Chun Han Wong, “China’s museums rewrite history to boost Xi,” Wall Street Journal, August 20, 2018, https://www.wsj.com/articles/sleight-at-the-museum-china-rewrites-history-to-boost-xi-1534766405.

[29] Douglas Zhihua Zeng, “China’s Special Economic Zones and industrial clusters: Successes and challenges,” World Bank blog, April 27, 2011, https://blogs.worldbank.org/developmenttalk/china-s-special-economic-zones-and-industrial-clusters-success-and-challenges.

[30] See photos of the Foxconn nets and jail-like bars on dormitory windows in Smith, China’s Engine chapter 1.

[31] World Bank, “China’s Special Economic Zones: Experience gained,” n.d., https://www.worldbank.org/content/dam/Worldbank/Event/Africa/Investing%20in%20Africa%20Forum/2015/investing-in-africa-forum-chinas-special-economic-zone.pdf.

[32] Nicholas R. Lardy, Markets Over Mao (Washington D.C.: Peterson Institute, 2014), 85.

[33] Yoko Kubot, “Apple’s China engineers keep products flowing as Covid shuts out U.S. staff,” Wall Street Journal, May 9, 2022, https://www.wsj.com/articles/apples-china-engineers-keep-products-flowing-as-covid-shuts-out-u-s-staff-11652094929; Ryosuke Matsui, “In China decoupling, companies still rely on Chinese know-how,” Nikkei Asia, March 17, 2023, https://asia.nikkei.com/Spotlight/Supply-Chain/In-China-decoupling-companies-still-rely-on-Chinese-know-how.

[34] Natsumi Kawasaki, “Eclipsed by Chinese rivals, Panasonic quits solar cells and panels,” Nikei Asia, January 31, 2021, https://asia.nikkei.com/Business/Electronics/Eclipsed-by-Chinese-rivals-Panasonic-quits-solar-cells-and-panels.

[35] Bloomberg, “China’s $220 billion biotech initiative is struggling to take off,” May 15, 2023, https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2023-05-15/china-biotech-stumbles-despite-220-billion-investment#xj4y7vzkg; Bloomberg, “Next China: losing mojo” May 19, 2023, https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2023-11-03/amazon-founder-jeff-bezos-announces-move-to-miami-from-seattle?sref=4KuSK5Q1; McGregor, op cit.; Matthew Johnson, “The CCP absorbs China’s private sector: capitalism with party characteristics,” Hoover Institution, September 2003, https://www.hoover.org/research/ccp-absorbs-chinas-private-sector-capitalism-party-characteristics; Max J. Zenglein and Jacob Gunter, “The party knows best: aligning economic actors with China’s strategic goals,” MERICS, October 2023, https://merics.org/en/report/party-knows-best-aligning-economic-actors-chinas-strategic-goals;

[36] Smith, China’s Engine, 2.

[37] Alexandra Harney, The China Price: The True Cost of Chinese Competitive Advantage (London: Penguin, 2008), 3.

[38] Floris-Jan van Lyun, A Floating City of Peasants: The Great Migration in Contemporary China (New York: New Press, 2006); Tom Miller, China’s Urban Billion (London: Zed, 2012); Chris Buckley, “Why parts of Beijing look like a devastated warzone,” New York Times, November 30, 2017, https://www.nytimes.com/2017/11/30/world/asia/china-beijing-migrants.html.

[39] China Labor Bulletin, “Introduction to China Labour Bulletin Strike Map,” May, 2022, https://clb.org.hk/en/content/introduction-china-labour-bulletin’s-strike-map: Marrian Zhou, “Factory strikes flare up in China as economic woes deepen,” NikkeiAsia, August 28, 2023, https://asia.nikkei.com/Business/Business-trends/Factory-strikes-flare-up-in-China-as-economic-woes-deepen; Gerry Shih, “’Everyone is getting locked up’: as workers grow disgruntled, China strikes at labor activists,” Washington Post, December 24, 2019, https://chinalaborwatch.org/everyone-is-getting-locked-up-as-workers-grow-disgruntled-china-strikes-at-labor-activists/.

[40] Chandini Monnappa and Phartiyal, “Apple supplier Wistron could not manage scaled up India plan, government report says,” Reuters, December 19, 2020, https://www.reuters.com/article/us-apple-india-wistron/apple-supplier-wistron-could-not-manage-scaled-up-india-plant-government-report-says-idUSKBN28T0C9.

[41] Smith, China’s Engine, chapter 2 and the sources cited therein. For a case study see, Qin Shao, Shanghai Gone (New York: Roman & Littlefield, 201).

[42] “Why China is so good at building railways,” Youtube, n.d., https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0JDoll8OEFE&list=RDCMUC9RM-iSvTu1uPJb8X5yp3EQ&start_radio=1&rv=0JDoll8OEFE&t=3. Also Shin Watanabe, “China Railway expands high-speed network as profits take back seat,” NikkieAsia, January 29, 2023, https://asia.nikkei.com/Business/Transportation/China-Railway-expands-high-speed-network-as-profits-take-back-seat.

[43] Manipadma Jena, “Land taken for Indian car factory returned to farmers, bears fruit,” Reuters, May 9, 2017, https://www.reuters.com/article/us-india-landrights-farming/land-taken-for-indian-car-factory-returned-to-farmers-bears-fruit-idUSKBN1851LI.

[44] Buckley, “Why parts of Beijing look like a war zone,” op. cit.; Lucas Niewenhuis, “Bejing evictions reach into the tens of thousands, destroying livelihoods of migrants,” China Project, November 30, 2017, https://thechinaproject.com/2017/11/30/beijing-evictions-reach-tens-thousands-destroying-livelihoods-migrants/; Tania Branigan, “Millions of Chinese rural migrants denied education for their children,” Guardian, March 14, 2010, https://www.theguardian.com/world/2010/mar/15/china-migrant-workers-children-education; Andrew Jacobs, “China takes aim at rural influx,” New York Times, August 29, 2011, https://www.nytimes.com/2011/08/30/world/asia/30china.html; Li Yuan, “China is deleting poverty, one video at a time,” New York Times, May 8, 2023.

[45] On the fate of the migrant workers see Li Yuan, “After building up China, they have nothing to fall back on,” New York Times, November 1, 2023. On the fate of the SOE workers see Dorothy Solinger, Poverty and Pacification: The Chinese State Abandons the Old Working Class (New York: Rowman& Littlefield, 2022) and Sarosh Kuruvilla et al., From Iron Rice Bowl to Informalization (Ithaca: Cornell, 2011). On the real beneficiaries of the dibao system see Jennifer Pan, Welfare for Autocrats (Oxford: OUP, 2020).

[46] Ding Yi, “China has more billionaires than the U.S. and India combined,” Caixin, February 26, 2020, https://www.caixinglobal.com/2020-02-26/china-has-more-billionaires-than-us-and-india-combined-hurun-report-101520792.html.

[47] Joseph Kahn, “The nation: party of the rich: China’s congress of crony capitalists,” New York Times, November 10, 2022; Su-Lee Wee, “China’s parliament is a growing billionaires club,” New York Times, March 1, 2018.

[48] David Barboza, “Billions in hidden riches for family of Chinese leader,” New York Times, October 25, 2012; “Xi Jinping millionaire relations,” op cit.; “Heirs of Mao’s comrades rise as new capitalist nobility,” Bloomberg, December 26, 2012, www. bloomberg.com/news/2012-12-26/immortals-beget-china-capitalism-from-citic-to-godfather-of-golf.html.

[49] World Bank, GINI Index, 2019, https://www.indexmundi.com/facts/indicators/SI.POV.GINI/rankings; Bert Hofman, “China’s common prosperity drive,” EAI, September 3, 2021, https://research.nus.edu.sg/eai/wp-content/uploads/sites/2/2021/09/EAIC-33-20210903.pdf.

[50] China’s Engine, chapter 6.

[51] Keith Bradsher and Joy Dong, “Suitcases of cash: How China’s money flows out,” New York Times, November 28, 2023.

[52] On illegal CCP cadre income see, again, China’s Engine, chapter 6. For the revelations about Chinese kleptocrats in the Panama Papers see Stuart Lau, “Chinese dominate list of people and firms hiding money in tax havens, Panama Papers reveal,” South China Morning Post, May 10, 2016, www. scmp.com/news/hong-kong/article/1943463/chinese-dominate-list-people-and-firms-hiding-money-tax-havens-panama; Patti Waldmeir and Tom Mitchell, “Panama Papers: Top officials tied to offshore companies,” CNBC News, April7, 2016, www.cnbc.com/2016/04/07/panama-papers-top-china-leaders-tied-to- offshore-companies.html.

[53] Smith, China’s Engine, 136ff.

[54] Eg. China and the Left: A Socialist Perspective, https://www.codepink.org/chinaandtheleft.

[55] Li Yuan, “China is deleting poverty,” op cit.

[56] Ibid.

[57] Li Yuan, “Chinese grads struggle to find work. Xi shrugs,” New York Times, June 2, 2023.

[58] World Bank, Four Decades of Poverty Reduction in China (Washington D.C., 2022), 2, Figure 1, https://thedocs.worldbank.org/en/doc/bdadc16a4f5c1c88a839c0f905cde802-0070012022/original/Poverty-Synthesis-Report-final.pdf; Indermit Gil, “Deep-sixing poverty in China,” Brookings Institute, January 25, 2021, https://www.brookings.edu/blog/future-development/2021/01/25/deep-sixing-poverty-in-china/; World Bank, Understanding Poverty, https://www.worldbank.org/en/understanding-poverty.

[59] World Bank, op cit.; Gil, op cit.

[60] Bert Hofman, op cit.; Li Qiaoyi, “600m with $140 monthly income worries top,” Global Times, May 29, 2020, https://www.globaltimes.cn/content/1189968.shtml.

[61] World Bank, CIA Factbook, https://www.cia.gov/the-world-factbook/field/population-below-poverty-line/;

U.S. Census Bureau, Poverty in the United States: 2021, https://www.census.gov/library/publications/2022/demo/p60-277.html.

[62] October 11, 2023, http://en.people.cn/n3/2023/1011/c90000-20081876.html.

[63] Jonathan Kaiman, “Inside China’s ‘cancer villages’” Guardian, June 4, 2013, https://www.theguardian.com/world/2013/jun/04/china-villages-cancer-deaths. For a survey of water and soil pollution, and food contamination, see Smith, China’s Engine, chapter 3.

[64] Mark T. Buntaine et al., “Citizen monitoring of waterways decreases pollution in China by supporting government action and oversight,” PNAS, July 12, 2021, https://www.pnas.org/doi/10.1073/pnas.2015175118.

[65] Shan Jie, “Groundwater 80% polluted,” Global Times, April 12, 2016, https://www.globaltimes.cn/content/978117.shtml.

[66] Jennifer Duggan, “One fifth of China’s farmland polluted,” Guardian, April 18, 2014, https://www.theguardian.com/environment/chinas-choice/2014/apr/18/china-one-fifth-farmland-soil-pollution.

[67] Bloomberg, “China says land the size of Belgium too polluted to farm,” December 31, 2013, https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2013-12-31/china-says-arable-land-size-of-belgium-too-polluted-for-farming?sref=4KuSK5Q1. See Smith, China’s Engine, 62-64 on the failure of cleanup efforts, notably Lake Tai.

[68] Louise Moon, “China’s parents haunted by melamine baby milk scandal still favour foreign brands,” South China Morning Post, February 22, 2022.

[69] See Smith, China’s Engine, chapter 3 for numerous examples. Also, Orang Wang, Editorial, “Action needed to put a lid on trade in baby milk formula,” South China Morning Post, March 2, 2019, https://www.scmp.com/comment/insight-opinion/article/2188379/action-needed-put-lid-trade-baby-milk-formula?module=hard_link&pgtype=article.

[70] Yanzhong Huang, Toxic Politics: China’s Environmental Health Crisis and its Challenge to the State (Cambridge: CUP, 2020), 31.

[71] Ibid. 32.

[72] Avraham Ebenstein, “Water pollution and digestive cancers in China,” Population Association of America papers, 2009, https://paa2009.populationassociation.org/papers/91541#:~:text=In%20summary%2C%20the%20results%20suggest,effect%20on%20digestive%20cancer%20rates; Tan Ee Lyn, “China’s ‘cancer villages’ bear witness to economic boom,” Reuters, September 16, 2009,https://www.reuters.com/article/uk-china-pollution-cancer/chinas-cancer-villages-bear-witness-to-economic-boom-idUKTRE58G00B20090917.

[73] Yanzhong Huang, “In China, food safety is threatened by an increasingly opaque political system, South China Morning Post, January 10, 2021, https://www.scmp.com/magazines/post-magazine/long-reads/article/3116884/china-food-safety-threatened-increasingly-opaque.

[74] Climate Action Tracker (CAT), n.d., climateactiontracker.org/China, and climateactiontracker/United States, accessed July 22, 2023; International Energy Agency (IEA). 2021. Global Energy Review 2021. Paris: IEA.www.iea.org/reports/global-energy-review-2021; Larsen, Kate, Hannah Pitt, Mikhail Grant, and Trevor Houser, “China’s greenhouse gas emissions exceeded the developed world for the first time in 2019.’ Research Note, May 6, 2021, Rhodium Group. rhg.com/research/chinas-emissions-surpass-developed-countries; IEA, “Global emissions rebounded to their highest level in history in 2021,” https://www.iea.org/news/global-co2-emissions-rebounded-to-their-highest-level-in-history-in-2021#.

[75] Michon Scott, “Does it matter how much the United States reduces its carbon dioxide emissions if China doesn’t do the same?” Climate.gov, August 30, 2023, https://www.climate.gov/news-features/climate-qa/does-it-matter-how-much-united-states-reduces-its-carbon-dioxide-emissions#:~:text=In%20fact%2C%20at%20China%27s%202021,up%20to%20the%20United%20States.

[76] IEA, Global Energy Review, March 2022, https://www.iea.org/reports/global-energy-review-co2-emissions-in-2021-2#.

[77] UN Environment Program, August 2, 2013, https://www.unep.org/news-and-stories/press-release/china-outpacing-rest-world-natural-resource-use. See also Elizabeth C. Economy and Michael Levi, By All Means Necessary: How China’s Resource Quest is Changing the World (Oxford: OUP, 2014).

[78] “United States consumption, E-The Environmental Magazine,” September 14, 2012, https://www.blueridgeoutdoors.com/go-outside/united-states-consumption/.

[79] Which I’ve criticized elsewhere, eg., Smith, Green capitalism: The God That Failed (WEA, 2016).

[80] Smith, China’s Engine, xviii-xix.

[81] Steven Lee Myers et al., “How China targets the global fish supply,” New York Times, September 26, 2022, https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2022/09/26/world/asia/china-fishing-south-america.html.

[82] Smith, China’s Engine, Introduction.

[83] Smith, China’s Engine, Introduction.

[84] “Smith, “Climate arsonist Xi Jinping: a carbon-neutral economy with a 6% growth rate? Real-World Economics Review, no.94, December 9, 2020, 52, http://www.paecon.net/PAEReview/issue94/Smith94.pdf.

[This article is one of several articles on Palestine-Israel that will be appearing in our Winter 2024 issue.]

[This article is one of several articles on Palestine-Israel that will be appearing in our Winter 2024 issue.]

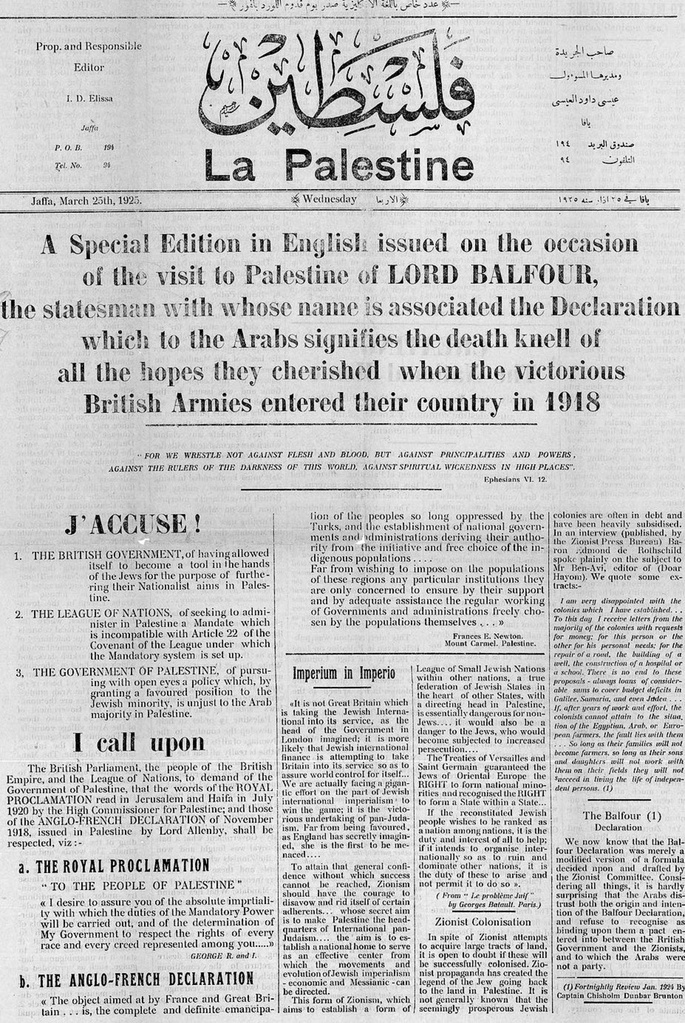

If Al-Qaeda and ISIS were the indirect products of the policies of US imperialism, Hamas is a direct product of Israel. A glimpse into the painful history of 75 years of conflicts and confrontations between Israel and Palestinians helps one better understand the latest Hamas/Israeli fighting that started on October 7, 2023.

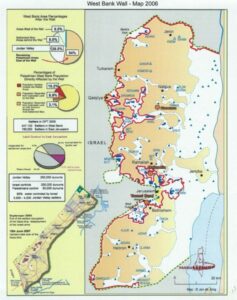

If Al-Qaeda and ISIS were the indirect products of the policies of US imperialism, Hamas is a direct product of Israel. A glimpse into the painful history of 75 years of conflicts and confrontations between Israel and Palestinians helps one better understand the latest Hamas/Israeli fighting that started on October 7, 2023. In 2002, Israel decided to build a massive concrete wall separating the West Bank and Israel, but actually placing much of the wall within the West Bank, in some areas penetrating more than 15 miles into the occupied territory. It also created large settlement complexes around East Jerusalem, effectively separating it from the West Bank.

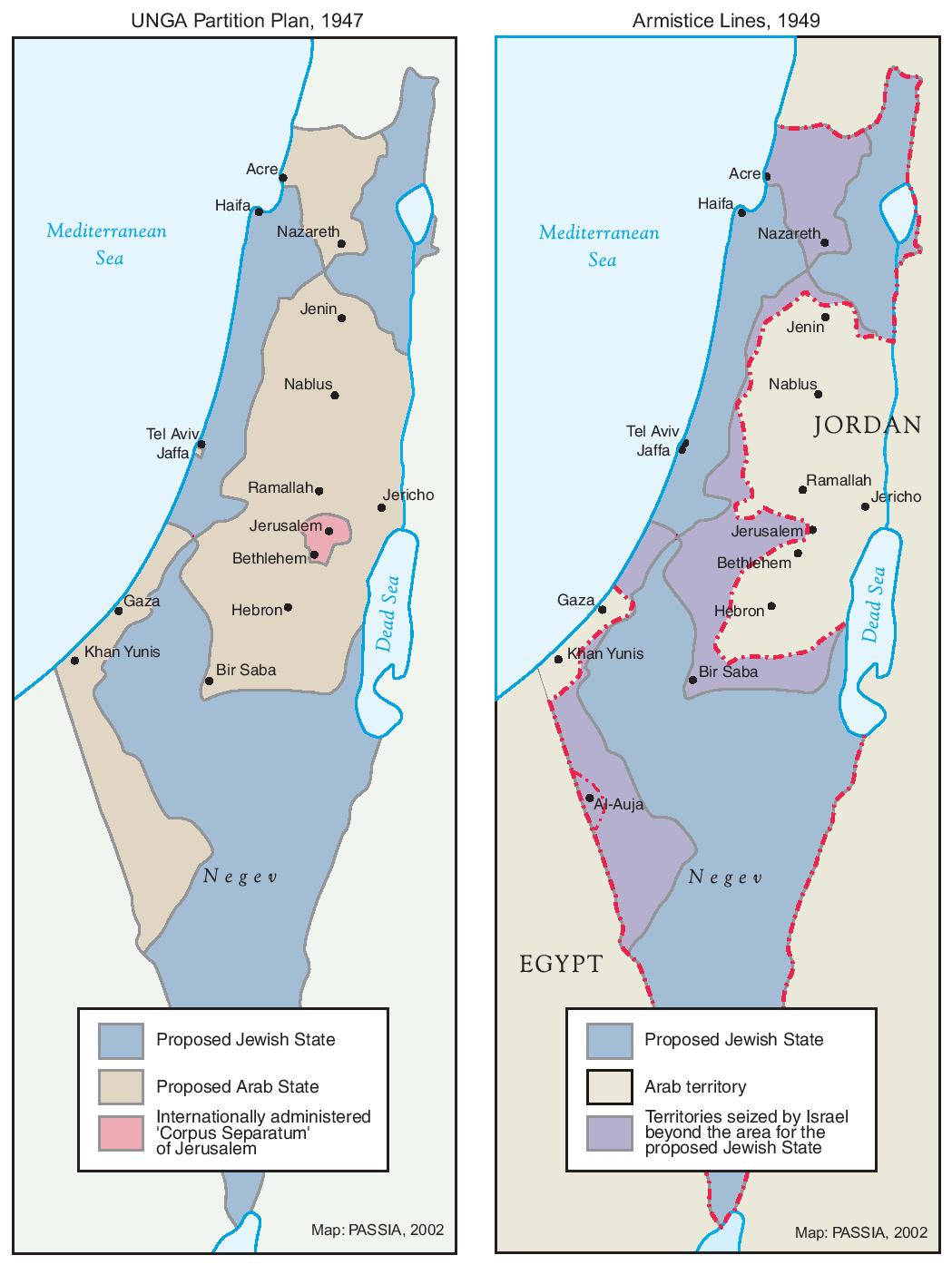

In 2002, Israel decided to build a massive concrete wall separating the West Bank and Israel, but actually placing much of the wall within the West Bank, in some areas penetrating more than 15 miles into the occupied territory. It also created large settlement complexes around East Jerusalem, effectively separating it from the West Bank. In 1947, Britain, which no longer had the option to maintain the mandate, handed over the “Palestine Question” to the United Nations. Two proposals known as the Minority Plan and Majority Plan were discussed in the General Assembly. The Minority Plan, favored by Iran, India and Yugoslavia, proposed a single federal state for two peoples, in which each nation would have full autonomy in its territory, but issues such as foreign relations, national security, and immigration would be dealt with at the federal level through a bicameral parliamentary system. This was a very progressive plan but was not acceptable to the Zionists who wanted to establish an independent Jewish state. The Majority Plan had the support of the United States and the Soviet Union and was adopted in Resolution 181, allocating much wider sections of land for the Jewish State compared to earlier British partition plans. Arab states, newly established with very limited diplomatic experiences, voted against both plans, though Israel accepted the Majority Plan. With the war raging on, Israel declared itself a state in 1948, and by the end of the war, it added more territories to what was allocated to it by the UN Resolution.

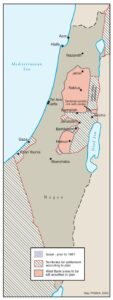

In 1947, Britain, which no longer had the option to maintain the mandate, handed over the “Palestine Question” to the United Nations. Two proposals known as the Minority Plan and Majority Plan were discussed in the General Assembly. The Minority Plan, favored by Iran, India and Yugoslavia, proposed a single federal state for two peoples, in which each nation would have full autonomy in its territory, but issues such as foreign relations, national security, and immigration would be dealt with at the federal level through a bicameral parliamentary system. This was a very progressive plan but was not acceptable to the Zionists who wanted to establish an independent Jewish state. The Majority Plan had the support of the United States and the Soviet Union and was adopted in Resolution 181, allocating much wider sections of land for the Jewish State compared to earlier British partition plans. Arab states, newly established with very limited diplomatic experiences, voted against both plans, though Israel accepted the Majority Plan. With the war raging on, Israel declared itself a state in 1948, and by the end of the war, it added more territories to what was allocated to it by the UN Resolution. With the establishment of the state of Israel, and its expansion through subsequent wars, numerous UN Resolutions have dealt with Israel and the Occupied Territories; more than 400 by the General Assembly, and over 222 by the Security Council– excluding 44 resolutions vetoed by Washington. One of the most important Security Council resolutions was 242 in 1967, which along with acknowledging the existence of Israel, demanded its withdrawal from the territories occupied in the 1967 war. Palestinians did not accept the Resolution, as it implied recognition of Israel. Egypt and Jordan accepted it, and later other Arab states made it a condition for the recognition of Isael. Instead of complying with the resolution, Israel came up with the Allon Plan, proposing the partition of the West Bank, allocating two separate areas assigned to Palestinians to be annexed to Jordan, and the rest remaining under Israeli control. The most intriguing part of the plan was that the two divided Palestinian areas were inside Israel and not bordered by the Jordan River, though the plan allowed a passage to Jordan through Jericho.

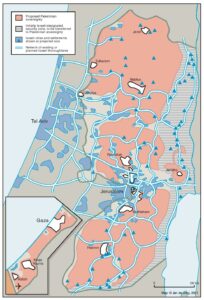

With the establishment of the state of Israel, and its expansion through subsequent wars, numerous UN Resolutions have dealt with Israel and the Occupied Territories; more than 400 by the General Assembly, and over 222 by the Security Council– excluding 44 resolutions vetoed by Washington. One of the most important Security Council resolutions was 242 in 1967, which along with acknowledging the existence of Israel, demanded its withdrawal from the territories occupied in the 1967 war. Palestinians did not accept the Resolution, as it implied recognition of Israel. Egypt and Jordan accepted it, and later other Arab states made it a condition for the recognition of Isael. Instead of complying with the resolution, Israel came up with the Allon Plan, proposing the partition of the West Bank, allocating two separate areas assigned to Palestinians to be annexed to Jordan, and the rest remaining under Israeli control. The most intriguing part of the plan was that the two divided Palestinian areas were inside Israel and not bordered by the Jordan River, though the plan allowed a passage to Jordan through Jericho. In 2000, President Bill Clinton hosted Israeli prime minister Edud Barak and Palestinian Authority chair Yasser Arafat at Camp David. Clinton and Barak proposed changes to the West Bank borders according to which Israel would annex 9-10 percent more of the West Bank and 9-10 percent more of the border with the Jordan River which would also be put under “indefinite temporary” [sic] Israeli control. In return, Israel would add 1-3 percent of its own territory in the Negev Desert to the Palestinian territories. Some unspecified parts of Area C would also go under Palestinian control, without any impact on Jewish settlements. Palestinians would be allowed to commute on a highway that would link Jerusalem to the Dead Sea, with Israel having the right to shut it down anytime it deemed necessary. Refugee issues remained unresolved. The proposal would give the Palestinian state administrative control over part of East Jerusalem without “sovereignty” over the Haram al-Sharif/Al-Aqsa Mosque, or the Temple Mount compound. Arafat declared that he could not possibly agree with the proposals and the summit failed. Arafat’s return to the West Bank coincided with the second Intifada, and Israel’s response included demolishing much of Arafat’s residence, leaving a small section for his impending house arrest.

In 2000, President Bill Clinton hosted Israeli prime minister Edud Barak and Palestinian Authority chair Yasser Arafat at Camp David. Clinton and Barak proposed changes to the West Bank borders according to which Israel would annex 9-10 percent more of the West Bank and 9-10 percent more of the border with the Jordan River which would also be put under “indefinite temporary” [sic] Israeli control. In return, Israel would add 1-3 percent of its own territory in the Negev Desert to the Palestinian territories. Some unspecified parts of Area C would also go under Palestinian control, without any impact on Jewish settlements. Palestinians would be allowed to commute on a highway that would link Jerusalem to the Dead Sea, with Israel having the right to shut it down anytime it deemed necessary. Refugee issues remained unresolved. The proposal would give the Palestinian state administrative control over part of East Jerusalem without “sovereignty” over the Haram al-Sharif/Al-Aqsa Mosque, or the Temple Mount compound. Arafat declared that he could not possibly agree with the proposals and the summit failed. Arafat’s return to the West Bank coincided with the second Intifada, and Israel’s response included demolishing much of Arafat’s residence, leaving a small section for his impending house arrest.

The people of Palestine have suffered from multiple oppressions for many years. Their homeland was occupied. They lost many of their youth. Their intellectuals were exiled or killed. Their children experienced war and explosions. Women experienced the loss of their homeland and their children.

The people of Palestine have suffered from multiple oppressions for many years. Their homeland was occupied. They lost many of their youth. Their intellectuals were exiled or killed. Their children experienced war and explosions. Women experienced the loss of their homeland and their children.

It is undeniabe that Luis Arce, the President of Bolivia, is no longer responding to the demands of his ex-boss, former President Evo Morales. Confrontations between the two men appear to be turning into what in Bolivia we call a ch’ampa war.

It is undeniabe that Luis Arce, the President of Bolivia, is no longer responding to the demands of his ex-boss, former President Evo Morales. Confrontations between the two men appear to be turning into what in Bolivia we call a ch’ampa war.