For generations, May Day, the International Workers Day celebrated by working people in more than 200 countries, was ignored in the United States, the country of its origin. In fact, the annual holiday is as American as cherry pie, commemorating as it does the 1886 nationwide general strike in which U.S. trade unionists — largely foreign-born — walked off the job in support of an eight-hour workday.

Back in 1886, when the typical work day was 10, 12 or even 14 hours long and joblessness was rife, the demand for a work day limited to eight hours at decent wages was viewed as radical. The eight- hour-day movement was spearheaded by two organizations, the craft-dominated Federation of Organized Trades and Labor Unions (the forerunner of the American Federation of Labor) and the Knights of Labor.

This bilingual union leaflet announced the Haymarket Square rally supporting the demand for an 8-hour workday and denouncing Chicago police assaults on strikers.An 1884 proclamation from the Federation pledged that “eight hours shall constitute a legal day’s labor from and after May 1, 1886.” A circular of the time calling for a massive work stoppage on that date read, “Lay down your tools, cease your labor, close the factories, mills and mines (and demand) eight hours of work, eight hours for rest, eight hours for what you will.” Nationwide, anywhere from 150,000 to 500,000 workers — the number is in dispute — answered the call, though the epicenter of the strike effort was indisputably Chicago.

This bilingual union leaflet announced the Haymarket Square rally supporting the demand for an 8-hour workday and denouncing Chicago police assaults on strikers.An 1884 proclamation from the Federation pledged that “eight hours shall constitute a legal day’s labor from and after May 1, 1886.” A circular of the time calling for a massive work stoppage on that date read, “Lay down your tools, cease your labor, close the factories, mills and mines (and demand) eight hours of work, eight hours for rest, eight hours for what you will.” Nationwide, anywhere from 150,000 to 500,000 workers — the number is in dispute — answered the call, though the epicenter of the strike effort was indisputably Chicago.

Today’s May 1 observance is also associated with Chicago’s infamous May 4 Haymarket Square tragedy that same year. Thousands of labor activists had gathered in the square that evening to protest law-enforcement attacks on the strikers. When the peaceful rally was winding down, riot police marched into the crowd, demanding that everyone disperse. An unknown assailant tossed a homemade bomb at the line of police, killing one. In the chaos that ensued, at least a dozen people were killed, including six more police officers, all from gunshot-related wounds. Eight of the movement’s leaders, two of whom were not even present at the rally, were charged with murder and conspiracy.

The prejudicial trial took place in a hothouse atmosphere. Typical was the Chicago Tribune’s demand for the deportation of immigrants it labeled “ungrateful hyenas” and “foreign savages who might come to America with their dynamite bombs and anarchic purposes.” The prosecution offered no evidence for its contention that the defendants plotted to target police at the demonstration; it argued simply that the remarks of the rally speakers constituted incitement to violence. All eight were found guilty of murder and four of the eight were eventually hanged. Authorities used the incident to launch a massive witch hunt and arrest hundreds of labor leaders, which put a halt to the eight-hour campaign for years.

The eight-hour day finally became a reality only in 1938, when the New Deal’s Fair Labor Standards Act made it a legal day’s work throughout the nation.

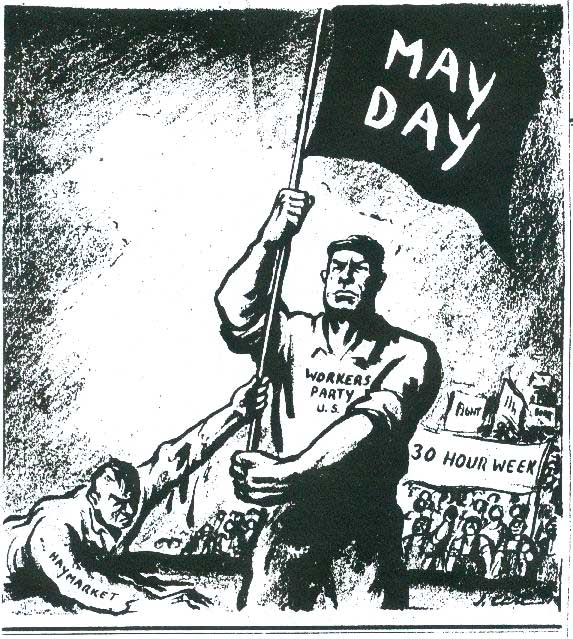

May 1 was adopted as a holiday internationally in 1890. In 1921, following a postwar Red Scare and the forced deportation of thousands of foreign-born workers— virtually all Southern and Eastern Europeans — May Day was named “Americanization Day” as a slap at foreign-born workers, then seen as dangerous radicals. During the Cold War, Congress sought to reclaim May 1 from “red sympathizers” by proclaiming it Loyalty Day, a day to reaffirm loyalty to the United States. The association of May 1 with communism was abetted by the Soviet Union, which used the date for parading military hardware and rattling sabers.

May 1 was revived as a day to mark worker rights in the United States in 2006, when immigrant workers participated in giant demonstrations on that day in New York and Los Angeles in their fight for immigration reform and a path to citizenship. For a second year, city unions, including the United Federation of Teachers, together with dozens of ethnic and community organizations joined a rally on May 1 at Manhattan’s Foley Square.

Uniting the twin fights for worker and immigrant rights that trace back to the birth of May Day, the rally participants protested attacks on public-sector workers, from union busting and attacks on public and private-sector workers, long-term unemployment, outsourcing and the shift of jobs overseas, the soaring cost of higher education and the increasing precarious conditions for even the college-educated, to anti-immigrant attacks and mass deportations and the need for equitable legislation establishing a path to citizenship.

In 2012, much of the Occupy movement added its support and presence as well.

Labor is heard: The labor-sponsored May Day rally at Foley Square in 2006 was everything that planners hoped it would be. Some 20,000 union members and supporters — the largest May Day rally in New York City since the 1930s — repeatedly cheered speakers defending teachers and other public-sector workers from attack and applauded calls for comprehensive immigration reform and an end to the stepped-up deportations of immigrants. More photos >>

The original version of this post was published here.

Fascinating story, well told.

Fascinating story, well told.