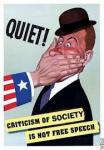

Introduction: On December 31, 2011 President Barack Obama signed into law the National Defense Authorization Act (NDAA) of 2011. Tucked into the bill providing the military with hundreds of billions of dollars were provisions authorizing the President to indefinitely detain in military jails those charged with providing "substantial support" to al-Qaida or the Taliban, and to prosecute these individuals in military tribunals. These provisions could easily be used against those who raised funds for an organization controlled by Islamic fundamentalists with ties to al-Qaida. In addition, the wording is so imprecise that it could lead to the detention of anyone who helped to organize a demonstration, or hosted a website, that promoted the views of Islamic fundamentalism as propounded by al-Qaida.

Introduction: On December 31, 2011 President Barack Obama signed into law the National Defense Authorization Act (NDAA) of 2011. Tucked into the bill providing the military with hundreds of billions of dollars were provisions authorizing the President to indefinitely detain in military jails those charged with providing "substantial support" to al-Qaida or the Taliban, and to prosecute these individuals in military tribunals. These provisions could easily be used against those who raised funds for an organization controlled by Islamic fundamentalists with ties to al-Qaida. In addition, the wording is so imprecise that it could lead to the detention of anyone who helped to organize a demonstration, or hosted a website, that promoted the views of Islamic fundamentalism as propounded by al-Qaida.

In signing NDAA (2011), Obama issued a finding stating that he would not detain any U.S. citizen in a military prison as authorized by the bill. In fact, his finding is not legally binding, and the statute remains on the books as enacted by Congress. Furthermore, any future president would not be bound morally or legally to the finding, and would be free to utilize its provisions.

The bill denies U.S. citizens fundamental rights guaranteed by the Constitution's Bill of Rights. The right to a trial by a jury of one's peers in a court of law that adheres to due process is an essential prerequisite to a genuinely democratic society. In enacting NDAA (2011), Congress and the President have taken a significant step toward military rule.

This is not the first time that the question of military tribunals has been raised. Indeed, the struggle to prevent military courts from claiming jurisdiction over civilians has been repeatedly fought since the United States was first founded. The issue has often become acute during times of war, when those in power are eager to sacrifice basic rights to the expediency of the moment. A critical episode in this continuing struggle came during World War I, when the federal government initiated a sustained campaign to quash dissent. As a result, fundamental civil liberties were trampled upon in the rush to jail radicals, pacifists, and militant trade union activists.

In the midst of this wartime hysteria, key members of Congress, with the support of military intelligence, pushed hard to expand the jurisdiction of military tribunals to include opponents of the war. This effort triggered an intense debate that foreshadowed the current controversy concerning NDAA (2011). In the end, President Woodrow Wilson blocked the move, and dissidents continued to be prosecuted within the civilian judicial system, where they were accorded a jury trial. A close examination of this debate can help us to better understand the dangers inherent in NDAA (2011).

The British Experience

Shortly after Britain's declaration of war on Germany on August 4, 1914, the Liberal government of Herbert Asquith moved to erect an elaborate legal apparatus to crush any opposition. Three days later, on August 7, 1914, the government introduced the Defence of the Realm Act. In its initial version, the Act banned any action hampering the war effort at docks and railways, and authorized the government to issue regulations to ensure this goal. Those accused of violating the statute or the regulations would be tried by courts-martial, that is military tribunals.[1]

Three weeks later, the government returned with a revised version of the Act. The revised statute extended the zones in which British citizens could be tried before a military tribunal to include any area used for the "training or concentration" of British troops. The Army and Navy high command then declared that the coastal areas of southern and western England, as well as the entire coast of Scotland and Ireland, were covered by the revised statute.[2]

The first two versions of the Defence of the Realm Act sailed through Parliament with minimal discussion and little opposition. In November, 1914, the Asquith government returned to Parliament with a new version, and found itself embroiled in a volatile debate. This time anyone, including British citizens, could be tried by a military tribunal for allegedly violating the statute, or the regulations issued to enforce it, anywhere within the United Kingdom. Furthermore, the death penalty could be levied against those who were found to be acting "with the intent of assisting the enemy."[3]

Debate on this provision in the House of Lords was extensive and heated. Peers were dismayed with the willingness of the Liberal government to nullify a key mainstay of British liberty going back to the Magna Carta of the 13th century. Richard Haldane, as Lord Chancellor and government spokesperson, admitted that "the principle of trial before a jury is a principle which is very deep" in British jurisprudence, "and one which we should all respect."[4]

In the course of this debate, the government agreed to come back to Parliament with a revised version of the statute. In accordance with this agreement, the government proposed the fourth and final version of the Defence of the Realm Act, which was approved by Parliament in March, 1915. The revised Act permitted British citizens charged with violating the statute or the regulations to choose which court system would be utilized to try them. Needless to say, civilians opted to be tried in a civilian court. One clause of the 1915 legislation gave the government an escape valve. An official proclamation could mandate courts-martial for British citizens violating the regulations "in the event of invasion or for special military emergencies arising out of the present war." This section was never invoked in Britain (England, Scotland and Wales), but such a proclamation was issued for all of Ireland in the immediate aftermath of the Easter Uprising of April, 1916.[5]

The regulations issued by fiat to enforce the Defence of the Realm Act proved to be as dangerous threat to civil liberties as the Act itself. Indeed, even after the 1915 legislation limiting the jurisdiction of military tribunals, the military still exercised tremendous power over civilians. The regulations permitted military commanders to ban anyone from a specified area, forcing the individual to move to another part of the United Kingdom. Another regulation authorized the military to raid any house or office to search for printed material that could "cause disaffection" from the war effort. Printing presses seized by the military during a raid could be destroyed to ensure that they were not used to produce seditious literature.[6]

These and other regulations gave the military immense powers to police dissidents within the United Kingdom. In the United States, President Woodrow Wilson was unwilling to grant the military such sweeping authority. Instead, the federal government relied on one regulation, Regulation 27. In addition to banning "false reports," or "statements likely to cause disaffection," it also prohibited statements or reports "likely to prejudice the recruiting, training [and] discipline" of the U.S. military.[7] This wording provided the basis for the Espionage Act of June 1917.

Warren and the Espionage Act

During the first months following the decision to enter the war, U.S. authorities relied on the British experience in developing a strategy to suppress dissent. President Wilson, through his confidante Edward House, turned to William Wiseman for advice. Wiseman headed the U.S. operations of the Secret Intelligence Service, or MI6, the British equivalent of the Central Intelligence Agency, but he also cultivated a close working relationship with House.

In January 1917, Wiseman began "working with federal authorities" on legal strategies to counter and disrupt the anti-war opposition. In doing so, he not only gained access to detailed information on the activities of U.S. intelligence agencies, but he was also able "to some extent [to] influence their actions." Wiseman quickly discovered that "various state and federal police authorities" were "at loggerheads, and without proper cooperation." He therefore "drafted a report showing [the] necessity for cooperation and much fuller powers."[8]

According to Wiseman, this report convinced the administration to formulate a "Conspiracies Bill" for Congressional approval. Wiseman also provided the Department of Justice with a complete copy of the Defence of the Realm Act, including the many regulations that had been issued to enforce it. He reported to his superiors that U.S. authorities had then "based their bill on it." Wiseman was not engaging in idle boasting.[9]

Charles Warren was the Assistant Attorney General assigned to draft the proposed legislation. A Harvard graduate, Warren had been involved in Democratic Party politics before joining the Justice Department in 1914, where he specialized in enforcing the Neutrality Act during the first years of the war. In October, 1917, Warren sent a copy of the Espionage Act as approved by Congress that June to Rufus Isaacs, Lord Reading, who had recently visited the United States as a special emissary of the British government. Warren pointed to the Espionage Act as a key indication of how "far this country has gone in the direction of your Defence of the Realm Act."[10]

Title I, Section 3 of the Espionage Act provided the federal government with the legal grounds to incarcerate hundreds of anti-war activists and radical union militants during World War I. Those convicted of violating this section could be imprisoned for up to twenty years. Its provisions closely followed key sections of the Defence of the Realm Act.

The most frequently used provision of Title 1, Section 3 of the Espionage Act provided that anyone who "shall willfully obstruct the recruiting or enlistment service" of the armed services during wartime would be in violation of the law. In 1918, dozens of Industrial Workers of the World (IWW) leaders received sentences of ten to twenty years in maximum-security federal prisons upon being convicted of violating this provision, in large part because the union’s newspaper had printed editorials criticizing the draft.

The actions of the federal government during World War I represented the most sustained assault on civil liberties in the history of the United States. The IWW was left in shambles, and the Socialist Party was a shell of the mass party it had once been. Nevertheless, prominent figures such as former president Teddy Roosevelt insisted that the Wilson Administration was too lenient, and that harsher measures were needed. This position found influential supporters within the federal government as well.

Traitors

Although Charles Warren had drafted the Espionage Act, and initially oversaw its enforcement, he was convinced that it provided an inadequate basis for the total suppression of radical dissidents and anti-war activists. Warren believed that it was essential to move the trials of dissidents from the civilian judicial system to military tribunals, which would be authorized to impose the death penalty on those convicted. The President disagreed, believing that the Espionage Act provided a sufficient basis to effectively quash any organized opposition to the war, and he therefore opposed the drive to expand the jurisdiction of military tribunals.[11]

Warren vehemently objected to the President's decision on this critical issue, so he continued to press for more drastic measures. He was convinced that two key flaws in the existing system would undermine government efforts to repress dissidents. Warren's first objection was that some of those convicted of violating the Espionage Act were released on bail pending final disposition of their legal appeals. In fact, federal district judges usually set such high bail terms that the great majority of defendants charged with violating the Espionage Act remained in prison while waiting their trial or appellate reviews. Still, a few well-known figures, such as Eugene Debs and Bill Haywood, were released on bail and remained free for months before their verdicts were upheld. Cases such as these incensed Warren.

In addition, Warren was convinced that activists would not be deterred by the lengthy prison sentences being imposed on those convicted under the Espionage Act. Dissidents would risk prison sentences convinced that they would be granted presidential pardons once the war ended. In the end, most political prisoners did not serve their full sentences, although IWW leaders remained in Leavenworth Federal Penitentiary, a brutally rigorous maximum security prison, for more than four years after the war had ended. Many of them never recovered from the harsh treatment they received as prisoners.

In Warren's view, only the death penalty could deter radicals from engaging in activities that might obstruct the war effort. Obviously, there could be no presidential pardon for those executed. Furthermore, a few executions would provide a signal warning to everyone who was thinking of joining an anti-war group.

In the spring of 1917, Warren developed a double-edged legal strategy to meet these perceived failings in the Espionage Act. He began by arguing that those who actively opposed the war, organized militant strikes, or engaged in sabotage were guilty of treason and should be executed. His original brief supporting this argument does not seem to be extant, but other sources, including a law review article, provide the essential points.

Charges of treason were frequently hurled at anyone who opposed the war. Sensationalized articles in the tabloid press spuriously claimed that dissidents were funded by the German government. These arguments were even made by members of the Cabinet. Postmaster General Albert Burleson categorized the anti-war press as "traitorous," thus defending his decision to bar socialist newspapers from the mails.[12] Nevertheless, Warren was moving much further, proposing that dissidents be tried as traitors, and, potentially, executed on that basis.

Treason is the only crime specified in the Constitution, with the wording derived from a British parliamentary statute of 1351. Article III, Section 3 of the United States Constitution specifies that treason is either the "levying of war" against the federal government, that is armed revolt, or "adhering to their enemies, giving them aid and comfort." The authors of the Constitution were concerned that this section could be misused, and thus they specified that a person could only be convicted of treason on the basis of two witnesses who would testify that the defendant committed an "overt act" to further the conspiratorial plot.

Throughout U.S. history, very few individuals have been convicted of treason. Indeed, the federal courts have narrowly limited the scope of the actions that can be defined as providing "aid and comfort" to an enemy in time of war. Already in 1806, Chief Justice John Marshall in writing a prevailing opinion acquitting Aaron Burr had held that treason "should not be extended by construction to doubtful cases," and that, instead, "crimes not clearly within the constitutional definition should receive such punishment as the legislature in its wisdom may provide."

The Espionage Act, which Warren had drafted, had been enacted to do exactly this. Nevertheless, Warren sought to vastly expand the scope of the treason charge to cover a wide range of activities including sabotage and organized opposition to the war and the draft.

The charge of treason had been devised to deter the citizens of a combatant nation from providing assistance to the government of an enemy nation. During the period from the start of World War I in August 1914 to the U.S. entry into the war thirty months later, German agents carried on an extensive program of sabotage directed at facilities in the United States that were producing goods for the British war effort. German agents also initiated rather meager attempts to finance pro-German propaganda, and to incite strikes in factories producing munitions for the British. After the United States declared war on Germany in April 1917, U.S. authorities, with the aid of British intelligence, quickly rounded up and detained most of those suspected of cooperating with German agents.

Warren's belief that the Espionage Act was inadequate did not stem from his fear of the activities of German agents, or those who cooperated with them. Instead, he focused on those on anti-war activists and radicals. In the summer of 1917, the federal government felt especially threatened by the Industrial Workers of the World, which had organized militant strikes in the timber camps of the Pacific Northwest and the copper mines of the West. In a letter to Attorney General Thomas Gregory on August 7, 1917, Warren denounced the IWW strikes as "treasonable."

The federal government viewed the IWW as a significant threat because it had shown its ability to coordinate effective strikes involving tens of thousands of workers. Still, prosecutions initiated on this basis would have represented a political disaster. Instead, the Department of Justice pointed to acts of violence that caused property damage to recalcitrant corporations. Over the years, the IWW had been vocal in its support for sabotage as a valid tactic in the class struggle, although it had been generally vague in specifically defining this tactic. Once the United States entered the war, and the IWW became a target of government repression, the union publicly disavowed the use of sabotage. Nevertheless, there is credible evidence that Wobblies committed acts of vandalism against strikebreakers during the timber strike that spread throughout the Pacific Northwest in the summer of 1917, and that union leaders sanctioned these tactics.

Thus, the broader issues became focused on the narrower question as to whether those alleged to have committed acts of sabotage could be prosecuted for treason. Warren understood that a charge of treason would be dismissed unless he could counter the guidelines set forward by Marshall in the Burr case. He therefore argued that the destruction of property being used "for the successful prosecution of the war may equally constitute treason, and giving aid and comfort to the enemy." Such actions were covered when "performed with the intent" of aiding the enemy. Warren insisted that in determining intent a defendant "must be held to intend the direct, natural, and reasonable consequences of his own act."[13]

Warren was making use of a legal standard of proof that allowed the government to gain convictions on the basis of a minimum of evidence. The "bad tendency" argument is rooted in British common law in relation to libel. A person can be prosecuted for statements uttered or printed that have the "tendency" to encourage listeners or readers to violate the law. The U.S. Supreme Court had ruled that the First Amendment did not protect statements that violated this rule.[14]

Warren was stretching the net cast by the "bad tendency" argument even further than previously. He was proposing that defendants be convicted of treason, that is of assisting the enemy, because their actions objectively aided the German cause. Thus, the prosecution did not have to prove that defendants intended to help the enemy, or even that their actions had resulted in any impact, as long as the government could establish the "natural and reasonable consequences" of these actions. This was an argument similar to that used by the government in prosecuting opponents of the war under the Espionage Act, but it required a further jump in the argument to infer a link between those charged with treason and the German government on the basis of the potential results of their actions, even when no evidence of such a link had been uncovered.

Warren had a difficult time finding any precedents for such a vast expansion of the scope of the charge of treason in U.S. case law. Instead, he turned once again to the British legal precedent. Specifically, he cited a ruling by Rufus Isaacs, who had presided as Lord Chief Justice over the trial of Roger Casement, an Irish nationalist involved in the Easter Uprising in Dublin in April 1916. Isaacs had held that any British subject who commits an act "which strengthens or tends to strengthen the enemies of the King in the act of the war against the King" is thereby giving "aid and comfort" to the enemy, and is, therefore, guilty of treason.[15] Casement had been executed on the basis of this ruling. The wording provides such sweeping grounds for prosecution that virtually any opposition to the war, or any strike, could be considered an act of treason.

Attorney General Gregory was prepared to expand the range of the treason charge to cover sabotage, holding that "the destruction of human life or property for the purpose of aiding the enemy" constituted a treasonous act.[16] Nevertheless, the Attorney General rejected Warren’s legal strategy, as it related to the IWW and sabotage. He was convinced that the treason statute failed to provide an effective basis for "dealing with the willful destruction or injury of war supplies or war industries." Treason was such a high crime, and the penalty for its commission so severe," that "the hostile intent" had to be "clearly demonstrated."[17] This represented an implicit rejection of Warren’s argument that intent could be inferred from the "natural and reasonable consequences" of an allegedly treasonous act.

Warren's proposal to levy the charge of treason against IWW leaders and anti-war activists never moved beyond the Department of Justice. The Administration believed that the death penalty was not needed, and would be unnecessarily provocative. In spite of Warren's objections, dissidents continued to be prosecuted under the Espionage Act throughout the last months of the war.

Martial Law

In conjunction with his plan to widen the scope of the charge of treason, Warren also proposed that Congress impose martial law throughout the United States. Those accused of treason would therefore be tried by military tribunals, and could be executed upon conviction. In a military court-martial, a defendant has far fewer rights, and appeals to a higher authority are far quicker. Furthermore, the judge in a military tribunal is not independent of the prosecution, but rather is an officer acting under orders from the same commanding officers who are directing the government's case.

Martial law nullified the fundamental right of habeas corpus, that is a defendant's right to request a review in civil court, before a civilian judge, where the prosecution has to provide credible proof that the accused has committed the crimes specified. Article I, Section 9 of the Constitution guaranteed the right to seek a writ of habeas corpus, and guaranteed that Congress could only suspend this basic right "when in case of rebellion or invasion, the public safety may require it."

A declaration of martial law, backed up by Congress, would have granted the armed forces enormous powers, while depriving citizens of fundamental rights. Fortunately, both Attorney General Gregory and President Wilson were wary of moving in this direction, so Gregory commissioned James Proctor to examine the precedents and evaluate the current situation within that context.

Proctor concluded that the prevailing conditions in 1917 made it "impossible" to declare martial law in any zone within the United States, and, in addition, neither the President nor Congress had the authority to suspend the right of habeas corpus. Although the United States was then engaged in fighting a total, global war, the country itself was peaceful, with "neither invasion, nor threat of invasion, nor any interference with the administration of law by the courts." Furthermore, martial law could not be imposed, and those charged with treason during time of war still maintained their right to a judicial review of their detention by seeking a writ of habeas corpus in a federal district court.[18]

Proctor was relying on a key Supreme Court decision in interpreting the Constitution on this issue. During the Civil War, the military commander of Union troops stationed in Indiana declared martial law, although the state was not a battle zone. In 1864, Lambden Milligen and four others were charged with plotting an armed attack on a prisoner of war camp holding Confederate soldiers. All five were tried by a military tribunal and sentenced to death. This verdict became a test case for the the limits of the military judicial system in the midst of the Civil War.

In 1866, the U.S. Supreme Court overturned the judgment of the military tribunal by a unanimous vote. A majority of the Court used the opportunity to issue a sweeping decision upholding the right of civilians to be tried in a civilian court even during a wartime emergency. Military tribunals established in areas "in which the federal courts were open" and in "unobstructed exercise" of their operations "had no jurisdiction" to try civilians from states that had not joined the rebellion for "any criminal offense."

The majority decision went on to explicitly reject a key prosecution argument. Attorneys for the prosecution had contended that martial law could be imposed anywhere in the United States since the entire country was mobilized for the war effort, and saboteurs were operating behind the battle lines. In this context, every state had become "in a military sense" a "theater of military operations." The majority opinion rejected this position even though the judges recognized that Indiana had been threatened with an invasion in the recent past, and might be in the future. Nevertheless, martial law could be imposed only when Confederate troops actually invaded, or when there was a credible and immediate threat of invasion. Until then, the fundamental right to a trial by jury remained intact and irrevocable.[19]

The logical implication of the Milligan decision, as Proctor correctly understood, was that martial law could not be declared in any region of the United States during World War I, and that federal courts therefore maintained their exclusive jurisdiction over civilians charged with any wartime crime, including treason. Warren attempted to circumvent this argument by insisting that World War I posed a set of challenges to government authority that were significantly greater than those posed by the Civil War. Indeed, "under the new organization of warfare introduced by Germany," which involved "enlisting the services of hosts of civilians" to "cause all the injury possible by undermining propaganda" or committing acts of sabotage, "the question arises whether the whole country has not become a part of the zone of operations of the war."[20]

In a total war, Warren argued, the economy of the entire country is mobilized to produce the munitions, armaments, and supplies required to supply an army of millions of soldiers. Any activities that might restrict output, whether by organizing strikes or distributing literature criticizing the government, provided a direct threat to the war effort and must be stopped. The imposition of martial law, followed by the execution of targeted dissidents, would crush the opposition and ensure that the war effort continued without disruption.

Supporters of the military tribunal sections of NDAA (2011 have advanced a similar argument. During a Senate debate on the bill, Senator Carl Levin, chair of the Armed Services Committee and a Michigan Democrat who acted as one of the key sponsors of NDAA, insisted that the entire United States had "been made part of the battlefield without any doubt." Indeed, "on September 11, the war was brought here by al-Qaida."[21]

This argument, as formulated by both Warren and Levin, is not persuasive. The Civil war was also a total war, albeit not a global one. Furthermore, the Confederates engaged in sabotage throughout the North, and encouraged "peace Democrats" to press President Lincoln to initiate talks leading to a negotiated settlement. Nevertheless, the Milligan case had upheld the basic constitutional right to a trial by jury in a civilian court operating in accordance with the due process of law, and this right prevailed even in the midst of World War I.

Gregory was not swayed by Warren's brief, and Proctor’s memorandum continued to set the parameters for federal policy throughout World War I. Warren responded by attempting to circumvent the Department of Justice by winning the support of key members of Congress. In January, 1918, Senator Robert Latham Owen, an Oklahoma Democrat, an ally of the Administration and a zealous supporter of the war effort, wrote to the President suggesting that Attorney General Gregory draft "a law authorizing the trial by court-martial" of "citizens of the United States detected in conspiracies involving treason."[22]

Woodrow Wilson firmly rejected Owen's suggestion as "a very serious mistake." Such a move would undercut the civilian judicial system by giving "the impression of weakness," thereby sending an implicit message of no confidence in the courts.[23] Although Wilson's definitive rejection of a proposal to expand the jurisdiction of military tribunals to include civilians was made in the context of the charge of treason, he would maintain a similar position when Warren advanced a new rationale for bringing anti-war activists before military courts-martial.

Spies

By August 1917, Warren had abandoned his effort to greatly widen the range of actions covered by the charge of treason for a new legal theory. Bypassing the touchy questions of treason and martial law, Warren argued instead that those who opposed the war, or committed acts of sabotage, were engaging in espionage. In his view, "owing to changes in the conditions of modern warfare," specifically the efforts made by Germany "to attack and injure the successful prosecution of the war" by a variety of covert means, anyone guilty of violating any section of the Espionage Act in wartime would be tried by a military tribunal as a spy and could be sentenced to death upon conviction.[24]

In drafting the Espionage Act, Warren had already equated opposition to the war to spying. Title 1 of this statute was headed Espionage and its first two sections targeted the usual activities of spies, obtaining secret military information and transmitting it to an enemy nation. Section 3, on the other hand, contained several broadly phrased prohibitions, clauses that were used to prosecute a wide range of radicals and anti-war dissidents. Warren's new legal theory went a great deal further, holding that those who opposed the war should be tried as spies by military tribunals.

Warren understood that the Milligan case would be cited in opposition to his new proposal. Although Warren recognized that the Supreme Court's ruling in the Milligan case had limited the times when martial law could be imposed, the ruling did not "necessarily limit" the "application of military law to civilians." The right to impose martial law arose "out of strict military necessity," while the authority of Congress to institute military tribunals derived from a very different source, the Constitution.[25]

The first article of the Constitution had authorized Congress to "declare war," "provide for the common defence," and "make rules for the government and regulation of the land and naval forces." From these general guidelines Warren argued that Congress had the power to override the basic rights guaranteed to citizens of the United States in the Bill of Rights when it determined that the risk to the armed forces of "the inherently dangerous effect" of certain acts "upon the military situation" required such legislation. Thus, he concluded, the Milligan decision had not limited the "power of Congress to legislate under Article 1, Section 8 of the Constitution."

Congress had already enacted legislation holding that civilians could be tried as spies in military tribunals in times of war. In 1806, Congress had held that "all persons not citizens of the United States" who were found "lurking as spies" in the vicinity of military installations could be tried by military tribunal and executed if convicted. In 1862, in the midst of the Civil War, Congress had amended this act to include "all persons" found "lurking" near fortifications.[26] This marked a significant extension of the scope of military justice, but it does not seem that anyone was actually prosecuted under the provisions of the amended act. Instead, Union generals relied on courts-martial created on the basis of martial law.

Warren argued that Congress had already asserted its right to determine who could be tried by a military tribunal for spying, and thus it could determine what acts were covered by the charge of espionage. The Constitution gave Congress "the power today to subject to court-martial civilians who commit acts just as injurious to the members of our army and navy" as those who spied on military fortifications.

In 1919, after the war had come to an end, Warren wrote a law review article defending the proposition that Congress could authorize military tribunals to try civilians for acts of sabotage, thereby greatly restricting the range of actions included in his argument. This time he also conceded that espionage had a clearly defined scope, which did not encompass acts of sabotage, but he nevertheless insisted that the Constitution had given Congress the authority to permit military tribunals to punish "the acts of the destructive enemy agent." After all, saboteurs might prove to be "more dangerous than spies."

Warren's argument in this article comes very close to that advanced by those supporting the relevant provisions in the National Defense Authorization Act. The damage caused on September 11, 2001 was sabotage writ large. The NDAA (2011) does not include a rationale for its sweeping provisions, but implicitly the argument holds that under the provision of the Constitution that gives Congress the responsibility to "provide for the common defense" of the United States, Congress can authorize the military to indefinitely detain anyone, including a U.S. citizen, who provides "substantial support" to al-Quaida and the Taliban. Such individuals, goes the argument, represent a significant threat to the national security of the United States during a time of hostilities, and thus are not protected by the Bill of Rights.

The argument that the Milligan decision did not limit Congressional authority to extend the jurisdiction of military tribunals to civilians is tenuous at best. The decision to overturn the conviction of Milligan could have been made on narrow technical grounds, but Judge David Davis used the opportunity to write an opinion intended to establish broad guidelines on the entire issue. His opinion held that "it is the birthright of every American citizen when charged with crime to be tried and punished according to law." The controversy concerning the jurisdiction of military tribunals is grounded in "the struggle to preserve liberty and to relieve those in civil life from military trials." Furthermore, the Constitution "is a law for rulers and people equally in war and peace." The argument that the fundamental rights embodied in the Bill of Rights "can be suspended during any of the great exigencies of government" is "pernicious," and "leads directly to anarchy or despotism." Although the Milligan case arose out of a trial held under martial law, Davis was making arguments that were designed to restrict the power of military trials at any time and whatever the legal rationale.

The Chamberlain Court-Martial Bill would have greatly increased the power of the military, and would have marginalized the Department of Justice in the effort to quash dissent during World War I. Neither Attorney General Gregory nor President Wilson was prepared to move in this direction, and the issue soon led to a tense confrontation between the President and members of Congress.

The President Responds

Warren did not just develop a legal theory justifying the use of military tribunals to prosecute civilians as spies for opposing the war and the draft, he sought to bypass the Department of Justice in order to win Congressional approval for his plan. In August 1917, Warren met with Senator Paul Husting of Wisconsin and Wheeler Bloodgood, an attorney who headed the Milwaukee County Council of Defense. Husting was eager to have anti-war activists tried by military courts. Wisconsin had a large population of German heritage, while Milwaukee was a bastion of the moderate wing of the Socialist Party of America. Husting and Bloodgood were incensed that the Milwaukee Leader, the newspaper of the Socialist Party of Milwaukee, was still being printed two months following the passage of the Espionage Act.

Victor Berger, the editor of the Leader and the leader of the right-wing of the Socialist Party, criticized the war as an imperialist venture, and yet he also urged his readers to obey all the laws, to register for the draft, and even to buy Liberty Loan Bonds to fund the war. Husting and Bloodgood realized that the war remained extremely unpopular in Wisconsin. They were worried that Berger’s cautious critique could still present a threat to government policy, and they were, therefore, anxious to establish a repressive apparatus that could immediately silence the Leader and dismantle the Socialist Party.[27] Warren proposed his new legal theory under which opponents of the war would be tried as spies in military tribunals as the solution to this problem. Convinced, Husting and Bloodgood persuaded Warren to write a memorandum providing the legal rationale underlying the proposed legislation.[28]

Warren was undermining administration policy on an important and sensitive issue, while continuing to occupy an influential position of responsibility. Attorney General Gregory was quick to respond. In mid-September, 1917, Gregory met with John Lord O’Brian, a prominent attorney in upstate New York with close ties to the Republican Party. As a result, a new division of the Justice Department was created on October 1, the War Emergency Division. As head of this new division, O’Brian supervised and coordinated the entire array of programs within the Justice Department aimed at suppressing radicals and disrupting the anti-war opposition. Warren was displaced, confined to prosecutions targeting those who violated the Trading with the Enemy Act.[29]

Obviously, Warren had been demoted in retaliation for his persistent advocacy of a policy that would have stripped the Justice Department of its leading role in the suppression of anti-war activities. Nevertheless, he remained an Assistant Attorney General, and he continued to promote the ideas formulated in his memorandum.

The issue finally came to a head in the spring of 1918. Once again, events in Milwaukee appear to have provided the spur to the conflict. A year earlier, soon after the United States had entered the war, Bloodgood had approached Mayor Daniel Hoan, who had been elected on the ticket of the Socialist Party, to probe his support for the war effort. Hoan reassured Bloodgood that he "did not favor" the anti-war resolution that the Socialist Party had recently passed at an emergency convention in St. Louis. Hoan pledged that he "was ready to assist the Defense Council" in its work, and, indeed, Bloodgood reported, Hoan had provided "active and very helpful assistance" along these lines. In public, Hoan dodged the issue of the war, but with municipal elections approaching in April 1918, Hoan, under pressure from Berger, signed on to the Party’s platform criticizing the U.S. entry into the war, and calling for a quick end to hostilities and a negotiated peace.[30]

At the same time as Milwaukee's municipal elections were scheduled, a special state-wide election was called to fill the seat vacated by the death of Senator Husting, who had been killed during a duck hunting trip in October, 1917. Berger stood as the socialist candidate on a platform urging immediate negotiations leading quickly to a peace treaty based on the principle of "no annexations and no reparations." His campaign attracted considerable support beyond the Socialist Party's Milwaukee stronghold, thereby demonstrating a widespread belief that the war should be brought to an end as soon as possible.[31]

In March 1918, Bloodgood returned to Washington, incensed at Hoan's public, albeit reluctant, opposition to the war, and deeply worried by the possibility that Berger could be elected Senator. Of course, the Administration shared Bloodgood's concerns. A month earlier, Berger and four other Socialist Party leaders, including Adolph Germer, its national secretary, had been indicted for violating the Espionage Act.[32]

Bloodgood was convinced that the approach taken by the Department of Justice would be ineffective, and Warren agreed. In Warren's view, only the death penalty could successfully intimidate the anti-war opposition, and thus safeguard the war effort. He insisted that "the moral effect of one man arrested and tried by court-martial was worth a hundred men tried by the Department of Justice in the criminal courts." Warren suggested to Bloodgood that Congress enact legislation mandating the Army to "deal with enemy activities."[33]

At Bloodgood's urging, Warren began circulating his memorandum. The memorandum, and a bill implementing its argument, were soon in the hands of Senator George Chamberlain, an Oregon Democrat and the chair of the Senate Military Affairs Committee. A few days later, Warren sent a draft to Chamberlain of a proposed bill embodying the legal argument formulated in the memorandum.

On April 16, Senator Chamberlain filed the proposed legislation, claiming that the United States had been "allowing treason to run riot."[34] He then proceeded to hold hearings on the bill before his committee. (Chamberlain may have been particularly eager to sponsor a bill extending the jurisdiction of military tribunals because Oregon had felt the impact of an IWW strike that had shut down the lumber industry of the Pacific Northwest for several months beginning in the late spring of 1917.)

Initially, Chamberlain received the support of a majority of the Senate Military Affairs Committee for his bill. Supporters of the bill specifically cited the success of Victor Berger's campaign for a Senate seat as a reason that a more draconian repression was essential. The proposed legislation specifically mandated that those charged in military tribunals under its provisions would be denied bail. According to Chamberlain, "the privilege of bail" had "been used in furthering spy plots."[35]

The Chamberlain Court-Martial bill, as drawn up by Warren, established a wide definition of espionage in time of war. Those who violated the Sabotage Bill, which would be signed into law by the President a few days after the Chamberlain bill had been introduced, were included. In addition, a provision of the bill barred the "spreading [of] false statements and propaganda." This replicated the Espionage Act, but Chamberlain went further by holding that those who printed and distributed literature that undermine the morale of those in the armed forces or that "oppose the cause of the United States" in the war were spies, and, thus, could be tried by a military tribunal. Those convicted of any provision of the bill would "suffer death."[36]

Warren testified in a closed, executive session during the first days of the Committee's hearings, voicing his dissatisfaction with the methods being used by the Department of Justice to suppress opposition to the war. This closed session was followed by a series of open hearings. Bloodgood appeared before the committee, expressing his dismay with the situation in Wisconsin. Colonel Ralph Van Deman, the chief of the Army’s Military Intelligence Division, testified it was essential to have tribunals that could "give quick and summary action" to quell those who opposed the war. Since civil criminal courts were "tied up with forms and red tape and law," military courts were necessary.[37]

Van Deman did not refer to one aspect of the proposed legislation. MID agents tended to view liberal opponents of the war as at least as much of a threat to the government as the IWW and the radical, left-wing of the Socialist Party. As a result, John Lord O’Brian and the attorneys at the War Emergency Division generally disregarded these reports as unreliable.[38] If military tribunals, operating under the auspices of the War Department, supplanted civil courts, the Army's Military Intelligence Division, and Van Deman, would largely determine who would be prosecuted for their opposition to the war.

Van Deman’s willingness to openly testify in favor of legislation in blatant contradiction to Administration policy is telling. It is hardly likely that he would have agreed to appear in public without the support of some of his superior officers. Woodrow Wilson understood that his authority was being directly challenged, and he moved quickly to meet the challenge. Warren was forced to resign from the Justice Department on April 19, only days after his testimony in executive session. Van Deman was quickly replaced as chief of the Military Intelligence Division, and then transferred to General Pershing’s headquarters staff in Paris. Van Deman’s career as an intelligence officer was over, although he remained an Army officer until 1929. His replacement, Marlborough Churchill, followed similar policies, but he did so more discreetly.[39]

Clearly, the Administration was embarrassed and angered by the Committee hearings on the Chamberlain Court-Martial Bill. It therefore moved forcefully to prevent the Chamberlain bill from being further considered by Congress. Attorney General Gregory sent an open letter to Representative William Gordon categorizing the bill as "exactly contrary" to the policy adopted by the Department of Justice. Furthermore, Gregory insisted that Warren had sent his brief and the proposed bill to Congress "without the consent or knowledge of the Attorney General," and without his approval.[40]

On April 20, President Wilson sent his own public letter to Senator Lee Overman, insisting that he was "wholly and unalterably opposed" to the Chamberlain Court-Martial bill. The bill was "unconstitutional" and its passage "would put us upon the level of the very people we are fighting and affecting to despise." Confronted with the imminent threat of a Presidential veto, Chamberlain reluctantly withdrew his bill from consideration. Warren's drive to vastly expand the scope of military tribunals had finally been thwarted.[41]

In the end, the Justice Department retained the primary responsibility for prosecuting anti-war dissidents. The federal government did not lessen its efforts to quash dissent, but it did so within the formal procedures set by the judicial system. Indeed, utilizing of the Espionage Act hundreds of activists were jailed for their opposition to the war, or for initiating strikes, and served lengthy sentences in federal penitentiaries.

Conclusions

World War I was intensely unpopular among millions of Americans, especially those in the Western states. In order to silence the opposition, the federal government imposed draconian measures that left the First Amendment’s guarantees of freedom of speech in tatters. The assault on basic rights was more drastic during World War I than in any other period of this country’s history. Nevertheless, as severe as the repression became, influential voices sought to make the repressive measures even harsher, to greatly expand the role of the military in suppressing domestic dissent. Only President Wilson's intervention blocked the passage of legislation greatly widening the jurisdiction of military tribunals.

The NDAA of 2011 placed into law many of the provisions that were advocated by Charles Warren during World War I. Citizens of the United States charged with a crime will be stripped of rights guaranteed by the Bill of Rights and will be subject to trial by a military tribunal. Only the vocal objections of an aroused populace can force the federal government to abandon its assault on basic rights. Understanding past debates on this vital issue is an important part of this process. Although the United States likes to present itself as a model of democracy, the historical record is very different. Those who are dismayed by the erosion of civil liberties since the destruction of the World Trade Center in September, 2001 need to consider these recent developments in the light of events in past times of crisis.

Footnotes

1. The Defence of the Realm Act, August 8, 1914, Acts of Parliament, 1914, Chapter 29.

2. The Defence of the Realm Act (Amended), August 28, 1914, Acts of Parliament, 1914, Chapter 63.

3. The Defence of the Realm Act (Consolidated), November 27, 1914, Acts of Parliament, 1914, Chapter 8.

4. Richard Haldane, November 27, 1914, House of Lords Debates, 5th Series, Volume 18, Column 205.

5. The Defence of the Realm Act (Amended), March 16, 1915, Acts of Parliament, 1915, Chapter 34; K. D. Ewing and C.A. Gearty, The Struggle for Civil Liberties: Political Freedom and the Rule of Law in Britain, 1914-1945 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2000), p.50.

6. The relevant regulations are Regulation 9 and Regulation 51. Charles Cook, ed., Defence of the Realm Manual, 6th edition, (London: HMSO, 1918), p. 1 and p. 184.

7. Cook, ed., Manual, p. 126.

8. William Wiseman to Mansfield Cumming, February 7, 1917, Box 4, Wiseman Papers, Yale University, New Haven Connecticut. Cumming was the first head of MI6, the original ‘C’ of James Bond fame. Wiseman’s report can not be located in his own papers at Yale, or the British National Archives in Kew Gardens or the U.S. National Archives at College Park, Maryland. It would make interesting reading.

9. Wiseman to Cumming, February 7, 1917, Box 4, Wiseman Papers.

10. Charles Warren to Rufus Isaacs (Lord Reading), October 12, 1917, Reading Papers, British Library, London, England. Warren also pointed to two other items that he drafted in this context. These were the Trading with the Enemy Act and a presidential proclamation allowing for the detention of enemy aliens.

11. The Administration would push to have the Espionage Act made even more draconian. The effort would result in the Sedition Act of May 1918, which amended the Espionage Act by specifying that anyone who used "any language intended to bring the form of government" or "the military or naval forces" into contempt "or disrepect" was subject to prosecution. Although the amendments further widened the scope of the Espionage Act, most prosecutions of anti-war activists during the last months of the war still proceeded under the original sections of the Act.

12. Albert Burleson to Woodrow Wilson, October 16, 1917, in Arthur S. Link, ed., Papers of Woodrow Wilson (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1983), 44:390.

13. Warren, "What Is Giving Aid and Comfort to the Enemy," Yale Law Journal (January 1918) 27:337.

14. In 1918, Eugene Debs would be prosecuted for violating the Espionage Act while speaking in Canton, Ohio. The indictment argued that one could voice opposition to the war or the draft "unless the natural and reasonable tendency and effect" of a speech would have "consequences forbidden by law." Debs' conviction in a federal district court was upheld in a unanimous decision by the Supreme Court.

15. Chief Justice Lord Reading in Rex v. Casement (1916), cited in Charles Warren, "What Is Giving Aid and Comfort to the Enemy," Yale Law Journal (January 1918) 27:3.

16. Thomas Gregory to Senator Morris Sheppard, February 25, 1918, File 9-19 (General), Classified Subject Files, Justice Department Records, Record Group 60, National Archives.

17. Gregory to Sheppard, February 25, 1918, 9-19 (General), Classified Subject Files, Record Group 60, National Archives.

18. Proctor, Memorandum to the Attorney General, April 14, 1917, File 190470, Department of Justice Records, Record Group 60, National Archives.

19. Ex Parte Milligan; 71 U.S. 1, 1866.

20. New York Times, April 17, 1918.

21. Congressional Record, December 1, 2011.

22. Woodrow Wilson to Robert Latham Owen, February 1, 1918, in Arthur S. Link, ed., Papers of Woodrow Wilson (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1983), 46:206. Owen's original letter is not in the Wilson Papers.

23. Wilson to Owen, February 1, 1918, in Papers of Woodrow Wilson, 46:206. Owen also proposed that "enemy aliens," that is recent immigrants from either Germany or the Austrian-Hungarian Empire, be prosecuted by military tribunals if charged with treason. The President was unsure of his position on this issue and referred it to Gregory. Nothing more was heard of the matter, as the Department of Justice asserted its authority to prosecute civilians, even aliens, on criminal charges.

24. New York Times, April 17, 1918. The wording of Chamberlain’s proposed legislation can also be found in Senate Committee on Military Affairs, Hearing, "Extending Jurisdiction of Military Tribunals," April 17, 1918, 65th Congress, 1st Session.

25. Charles Warren, "Spies and the Power of Congress to Subject Certain Classes of Civilians to Trial by Military Tribunal," American Law Review (March 1919): 53:201.

26. Warren, "Spies and the Power of Congress," American Law Review (March 1919): 53:206-7

27. Wheeler Bloodgood, Testimony, April 17, 1918, "Extending Jurisdiction of Military Tribunals."

28. Bloodgood, Testimony, April 17, 1918.

29. John Lord O’Brian, Oral History, Columbia University, pp. 229-30, 234. Warren wrote the Trading with the Enemy Act as well as the Espionage Act.

30. Bloodgood, Testimony, April 17, 1918, "Extending Jurisdiction of Military Tribunals."

31. The special election for Wisconsin's U.S. Senate seat held in April 1918 was a three-way race, with Irvine Lenroot, the Republican candidate, winning a plurality of votes. Berger received more than 25% of the vote, a very respectable result. He would go on to be elected to the U.S. House of Representatives in November 1918.

32. The five Socialist Party leaders were convicted of violating the Espionage Act in February 1919, and Berger received a twenty-year sentence. Ultimately, in January 1921 the U.S. Supreme Court overturned the convictions on the basis of the blatant bias evidenced by Judge Kenesaw Landis.

33. Bloodgood, Testimony, April 17, 1918, "Extending Jurisdiction of Military Tribunals."

34. New York Times, April 17, 1918.

35. New York Times, April 17, 1918.

36. New York Times, April 17, 1918.

37. Ralph Van Deman, Testimony, April 19, 1918, "Extending Jurisdiction of Military Tribunals."

38. Alfred Bettman to John Lord O’Brian, Memorandum, July 11, 1918, File 186701-39, Straight Numerical Series, Department of Justice Records, Record Group 60, National Archives. Bettman had looked at the MID files for Pittsburgh, but it is clear that his dismissal of the MID as an effective intelligence agency is obvious. Bettman was so disdainful of the MID that he questioned "what value there" was "to the Government in using the time and energy of these investigators" for "the accumulation of this sort of matter."

39. New York Times, April 23, 1918. Warren testified before the Senate Military Affairs Committee on April and he was forced to resign on April 19, 1918.

40. Thomas Gregory to William Gordon from the New York Times, April 23, 1918. The article gives the letter in full, but does not supply its date. It was written some time between April 19 and April 22, 1918.

41. Woodrow Wilson to Lee S. Overman, April 20, 1918, from the New York Times, April 23, 1918.

Leave a Reply