Which came first, your interest in politics or your interest in cartooning?

They actually began together, when I was 13 or 14, with a badly drawn, over-the-top, heartfelt diatribe against my mother’s consumerism. Even though I was just a white, middle class teenager in Connecticut, I was indignant about inequality and injustice.

How did you get started as a political cartoonist?

My first political cartoons were published in 1963, when, as a junior at Carleton College in Minnesota, I drew for the official student paper and then for one of the first underground newspapers of the 1960s (the paper’s name changed with every issue). The paper was the voice of a group of liberal, radical, and socialist students on the campus (including several New Politics readers) who engaged the Carleton administration in a struggle against in loco parentis that anticipated the Berkeley Free Speech Movement (FSM). After thirteen issues distributed to every student on campus, the administration finally suppressed the paper by threatening us all with suspension (but then gave up on in loco parentis the following year). Great fun!

After my junior year I married a fellow plotter, Kit Lyons, and we transferred to Berkeley in the summer of 1964, where we participated in the founding of the Independent Socialist Club (ISC), just before the Free Speech Movement, FSM, exploded. Thrilling times. My first ISC leaflets and newsletters were etched into mimeo stencils—lots of dancing Marxs, Lenins, and Rosa Luxemburgs. A wonderful, curmudgeony Trotskyist printer taught me how to prepare art for offset reproduction.

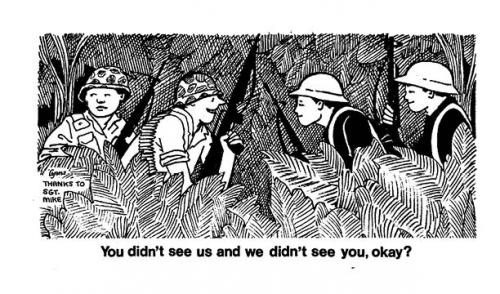

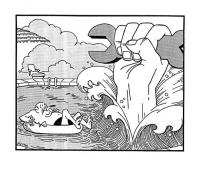

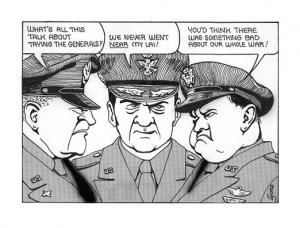

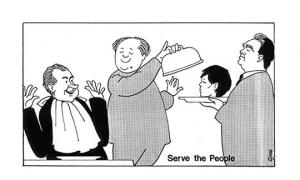

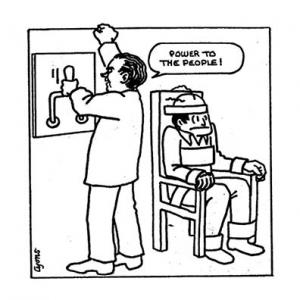

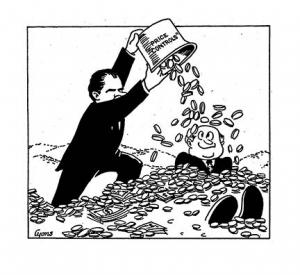

I spent the rest of the 1960s working for a wide range of radical and movement organizations—SDS, the Farm Workers, the Peace and Freedom Party, the Black Panther Party, and many others—and became a full-time staffer for the International Socialist (IS) newspaperWorkers Power in 1969. My work appeared in Liberation News Service, the left’s alternative to AP and UP. I illustrated Barbara Garson’s MacBird, which was translated into many languages, and went on to become a stage play. Most of my cartoons in the sixties and seventies were collaborations with Kit and other members of the ISC and IS.

|

|

|

|

Could you say something about your impressions of the underground comix world? Did you read the comics that people like Crumb and Shelton were producing? Were you offended by their sexism or inspired by their iconoclasm?

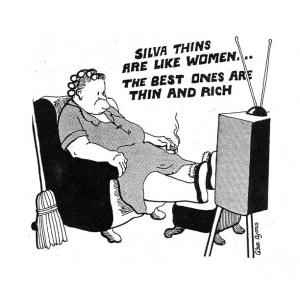

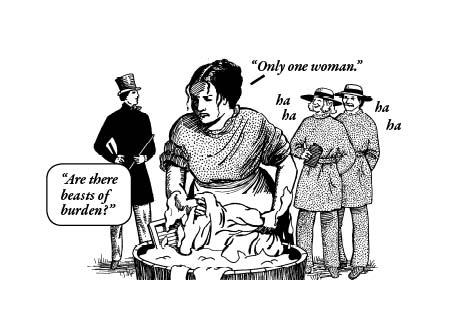

I loved the Fabulous Furry Freak Brothers—the joyous, anarchic craziness of it. It was such a celebration of the anything-can-happen spirit of the times, especially in California. I hated R. Crumb’s depiction of women. There was so much open sexism at the time, which is why, of course, women’s liberation was so . . . liberating. I tried to join the sign painters union, but was turned down because I “wouldn’t be comfortable at the all-male meetings.” On the other hand, a women’s group I had just joined informed me, by phone, that they had voted to become lesbians. Was I in? I said I’d only been married (to a man) a little while, but liked it so far, so no.

I loved the Fabulous Furry Freak Brothers—the joyous, anarchic craziness of it. It was such a celebration of the anything-can-happen spirit of the times, especially in California. I hated R. Crumb’s depiction of women. There was so much open sexism at the time, which is why, of course, women’s liberation was so . . . liberating. I tried to join the sign painters union, but was turned down because I “wouldn’t be comfortable at the all-male meetings.” On the other hand, a women’s group I had just joined informed me, by phone, that they had voted to become lesbians. Was I in? I said I’d only been married (to a man) a little while, but liked it so far, so no.

Who were some of your favorite cartoonists? Were there particular cartoonists who inspired you when you first started drawing cartoons for publication?

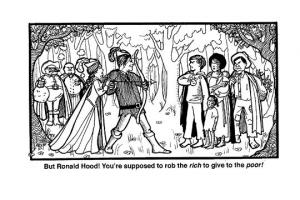

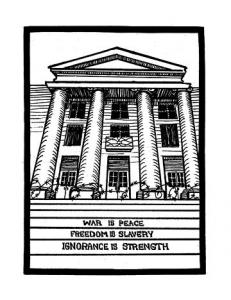

I grew up revering Ernest Shepard, illustrator of Wind in the Willows — his wit, delicacy, and black and white line. Beardsley’s dramatic black and white contrasts were a big influence, as were Hilary Knight’s Eloise drawings, and Crockett Johnson’s Barnaby. The French protest posters of 1968 influenced my style, as well as many of the other artists being published in Liberation News Service, and all the great political cartoonists of the past — from Thomas Nast to Balfour Ker to Carlo of the Workers Party/Independent Socialist League. I love Phil Evans’ British breeziness, and Gilbert Shelton’s Fabulous Furry Freak Brothers. Dan Perkins’ This Modern World is just the best. Why he hasn’t convinced everyone to see reason, I don’t know.

Gilbert Shelton’s Fabulous Furry Freak Brothers. Dan Perkins’ This Modern World is just the best. Why he hasn’t convinced everyone to see reason, I don’t know.

What kind of comics did you create once the sixties were over?

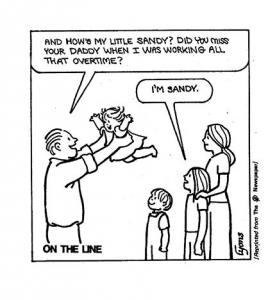

It was a nice change from the tanks and guns to be invited to do a section in Trina Robbins’ It Ain’t Me Babe comic in 1970. Three of us in that group were pregnant, including me, and Trina had just had  a baby. Sadly, just as I had found an exciting women’s group, we moved to Detroit, where I refocused on socialist and trade union cartoons and illustrations, and layouts for Worker’s Power.

a baby. Sadly, just as I had found an exciting women’s group, we moved to Detroit, where I refocused on socialist and trade union cartoons and illustrations, and layouts for Worker’s Power.

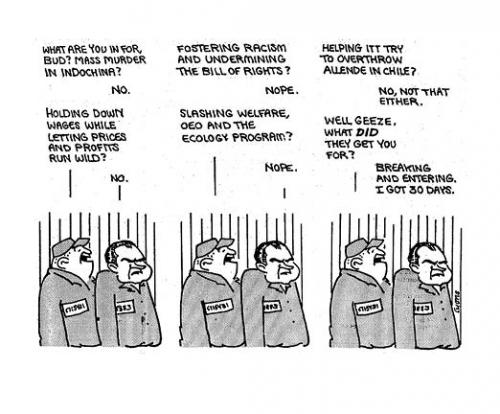

I was always able to do cartoons on subjects that I cared passionately about, including women’s issues. In Detroit, our milieu was the International Socialists. Some members had industrialized; Kit and I put out the newspaper, and did work for rank and file caucuses and other allied groups, as we had in Berkeley and Oakland.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

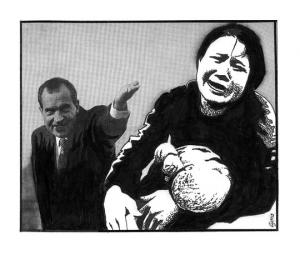

It was a wonderful period, but by 1973 I was feeling burned out—politics overload—and got an MA in Art History from Wayne State, and went on to the University of Delaware in 1975. My interest was in women’s art history; I began research at a time before there were any books on women artists, and almost no art by women was on view in museums. Women artists have definitely been an inspiration to me, Kathe Kollwitz in particular.

It was a wonderful period, but by 1973 I was feeling burned out—politics overload—and got an MA in Art History from Wayne State, and went on to the University of Delaware in 1975. My interest was in women’s art history; I began research at a time before there were any books on women artists, and almost no art by women was on view in museums. Women artists have definitely been an inspiration to me, Kathe Kollwitz in particular.

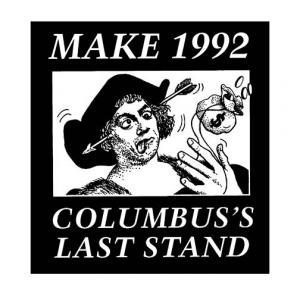

From 1975 to 2009 — a long time! — I was in grad school, raised three children, was a staff member at Sudbury schools in Maine and Maryland, and worked as a graphic designer, book designer, and illustrator. Kit and I haven’t been very politically active since Detroit, although our politics haven’t changed. In 2009 I retired from teaching, and contributed artwork to a book, Vive La Revolution!: An Appreciation of Joel Geier, and the publicity for an IS reunion, collecting old cartoons and doing some new ones. That led to being asked to contribute cartoons to New Politics, which I’ve been doing ever since.

I’m also currently working on a section in Paul Buhle’s forthcoming book, Bohemians. My section is on nineteenth-century utopian communities, including the very funny, not-so-utopian Fruitlands.  My involvement with this project and with New Politics has been an honor. It’s exciting to be back from burnout, although the world seems even more messed up than before.

My involvement with this project and with New Politics has been an honor. It’s exciting to be back from burnout, although the world seems even more messed up than before.

Thanks for this Article.

Thanks for this Article. Really Nice.