Seventy years after the end of World War II and the defeat of fascism and Nazism, the extreme right is on the rise in almost every European country. The last elections for the European Parliament were instructive in this regard, with electoral gains made by Europhobic, racist, and/or protofascist formations: UKIP (the United Kingdom Independence Party), the Party of the People of Denmark, the Austrian Freedom Party, the Swedish Democrats, the Alternative for Germany, Italy’s Northern League, and finally, the Hungarian Jobbik and the Greek Golden Dawn.1 In France, with 24.9 percent of the votes, the French National Front (FN) emerged as the largest party. The dramatic growth of Marine le Pen’s formation—from 6.3 percent in the European elections of 2009—did not end there. In the first round of France’s regional elections, in March 2015, the FN won 25.2 percent of the votes. This was an exceptional achievement for that type of election, evidence of the party’s increased territorial spread and growing appeal.

Seventy years after the end of World War II and the defeat of fascism and Nazism, the extreme right is on the rise in almost every European country. The last elections for the European Parliament were instructive in this regard, with electoral gains made by Europhobic, racist, and/or protofascist formations: UKIP (the United Kingdom Independence Party), the Party of the People of Denmark, the Austrian Freedom Party, the Swedish Democrats, the Alternative for Germany, Italy’s Northern League, and finally, the Hungarian Jobbik and the Greek Golden Dawn.1 In France, with 24.9 percent of the votes, the French National Front (FN) emerged as the largest party. The dramatic growth of Marine le Pen’s formation—from 6.3 percent in the European elections of 2009—did not end there. In the first round of France’s regional elections, in March 2015, the FN won 25.2 percent of the votes. This was an exceptional achievement for that type of election, evidence of the party’s increased territorial spread and growing appeal.

For months now, the political situation has been universally described as “exceptional.” Yet reading the wealth of articles and analyses of an allegedly unprecedented phenomenon, one finds a lot to be desired. Some bemoan the failure of an undifferentiated “left” to respond credibly to this new right that appears to have emerged from the deepest recesses of European history, while others worry about the political direction of the parties in government, the so-called “mainstream” parties. Of particular concern are the European socialist parties, pressured to follow the siren song of political “modernization,” and even at times to carry its torch, when it is in so many respects a reactionary, “regressive modernization.”2

To this is often added an inventory of the great upheavals that have shaken Europe since the fall of the Berlin wall, thus finding at least a partial explanation for the rise of the right in the economic crisis: the emergence of a global “post-Fordist” society, the end of the “great” ideologies, the crisis of political representation and of the governing parties, a general depoliticization of society, the rise of Reality TV democracy, and the concomitant reduction of politics to personalities. In short, it is a great whirlpool, in which are mixed together deeply rooted common sense and concrete analysis of a specific historical conjuncture, rendering it difficult to separate the incidental from the essential. This indeterminacy is likewise connected to the difficulty of clearly identifying, categorizing, and defining what is really included under the term “extreme right”—both because it is not possible to simply reduce what goes under this name today to its historical fascist or fascist-leaning matrix, and because a key strategy of the new formations is to confuse the political terms of reference.

Given the analytical difficulties that this phenomenon raises, one cannot help but recall the words written in exile in 1938 by Angelo Tasca, one of the founders of the Italian Communist Party, regarding another political movement new at the time: “To define fascism, one must write its history, … for there are many fascisms, each harboring multiple, at times contradictory, tendencies, which can evolve to the point of changing even some of their essential features.”3 In this short article, I cannot attempt to provide a complete map of the radical right in Europe. But I hope to delineate a few key tendencies by moving beyond the synchronicity of the journalistic snapshot, namely, by inscribing my reflection in the multiplicity of the phenomenon and the discordance of its social time.

The Rightward Swing

Looking back at the developments of the last decade, one is struck by the magnitude of political, social, and cultural backlash to an economic and social crisis of a depth that seems like a slow-motion replay of the Great Depression of the 1930s: the collapse of industrial output, commercial activity, and stock markets; skyrocketing economic inequality thanks to both rising unemployment and falling wages; and ballooning national debt leading to the brutal imposition of structural adjustment programs on Western European countries, notably on the so-called PIGS (Portugal, Ireland, Greece, and Spain, a group that Italy has joined). In fact, between the 1987 Wall Street crash and the subprime crisis of 2007-2008 there was a crisis every two years on average, implacably hitting the living and working conditions of wage-earners.4 The balance of forces in the workplace shifted radically and durably in favor of employers. Thus, since the 1980s, the class compromise that was established after World War II in European societies has undergone a series of neoliberal counter-reforms, whose effects at the workplace led some to speak of the birth of a post-Fordist society. More prosaically, the notion of post-Fordism includes both the changes in the structures of capitalist production (the burgeoning new information and communication technologies) and in the labor force: flexibilization and subsequent feminization of labor markets; outsourcing and the dislocation of social life; the visible decline of the working class, for itself but not in itself; and the weakening of forms of solidarity and social ties (atomization). Yet the breadth of the right’s counter-offensive cannot be understood without taking into consideration the “laws, decrees, regulations, and directives expressly thought of and approved by parliament under pressure from industrial and financial lobbies for the two purposes of weakening the working and middle classes and simultaneously increasing the power of the ruling class.”5 European societies had to relearn at their own expense Antonio Gramsci’s lesson, that it is not an abstract agreement that safeguards the rules of democracy, but only the organic relation of forces in society, which is put to the test and must be re-established in each new situation.

These developments were accompanied by wide-ranging socio-cultural changes, including an attack on the welfare state, crude historical revisionism, the sanctification of personal responsibility, and the stigmatization of the unemployed and of “foreigners.” These strong trends, already present from the end of the 1980s, became entrenched as economic crises followed one another, slowly but surely transforming the horizons and the political and social legitimacy of social struggles. As Warren Buffet concluded in 2006, “There’s class warfare, all right, but it’s my class, the rich class, that’s making war, and we’re winning.”6

The backlash of the last ten years appears all the more significant as it is accompanied by “dynamics of adaptation for the worse” tied to a kind of “trivialization of social injustice” and the dissolution of the essential principles on which people’s relation to civil society and to the state had rested.7 This is particularly true in Italy, which saw the collapse, after twenty years of Berlusconism, of one of the most important workers’ movements in Western Europe with barely any struggle, and then, at the turn of the twenty-first century, the demise of Rifondazione Comunista, a political party that until the emergence of Syriza in Greece and Podemos in Spain stood out in the landscape of the militant left for its capacity to make the connection with newly mobilized social sectors.

These processes did not unfold linearly and cannot be generalized to the totality of Europe (the capacity of resistance and bucking the tide by the people of Greece today is proof of that). The economic crisis has also triggered a crisis in the legitimacy of neoliberalism and a broad political contestation. Since the mid-1990s, various social movements have attempted to counter from below the neoliberal reforms that were marketed as ineluctable and necessary for avoiding the worst. After the anti-globalization protests came the Spanish Indignados and the Occupy movement, which put in motion a new repertory of political action (of which Web 2.0 has been but one aspect) and above all defended a new way of conceptualizing politics, breaking with the traditions of the mainstream left and the large trade unions.

Too quickly relegated by the press and parts of the institutional left to the pejorative category of populism and anti-politics, these movements constituted jolts whose full impact is yet to be determined. But at least so far in the vast majority of cases, they have resulted neither in the constitution of new political organizations nor in the delineation of a strategic horizon on which the myriad of struggles that took place in Europe against all hope (and repressed in so many ways) over the last decade could be made to converge.8 This is perhaps linked to the underestimation of the present as it is, or at least of the impact of the social, political, and economic transformations that have unfolded since the 1980s. The counter-revolution unleashed by the dominant classes, “using the crisis to construct a majority,” has irrevocably changed our living conditions, “working on and through us.”9

Sub-cultural Hegemony

and “Liquid Times”

In 1988, Stuart Hall warned the left against its dangerous failure to comprehend the implications of the “authoritarian populism” he saw represented by Margaret Thatcher’s government: “Unless the left can understand Thatcherism—what it is, why it arose, what its historical specificity is, the reasons for its success in redrawing the political map and disorganizing the left—it cannot renew itself because it cannot understand the world it must live in if it is not to be ‘disappeared’ into permanent marginality.”10 Hall advocated a “return to the subjective” as a way of fully grasping the impact of the extraordinary dissemination of that orthodoxy in the society at large. Inspired by Lenin, Hall argued that in that moment “absolutely dissimilar currents, absolutely heterogeneous class interests, absolutely contrary political and social strivings [had] merged, and in a strikingly ‘harmonious’ manner” constituted a new political bloc and a new way of conceiving the political terrain.11

Based simultaneously on the search for “active popular consent” and on coercion (restricting and then repressing collective freedoms), this “authoritarian populism” deployed a strong array of cultural tropes for its ideological legitimation: the end of history (Fukuyama); the emphasis on the value of individual liberties—of individuals without individuality; the stigmatization of rights, and in particular social rights; and last but not least, the widespread idea that There Is No Alternative. This ideological process has been so successful that “someone [could say] it is easier to imagine the end of the world than to imagine the end of capitalism.”12 This no doubt constitutes one of the greatest ideological victories of capitalism’s organic intellectuals.

However, although in recent years the crisis of neoliberalism has also put its instruments of ideological legitimation in crisis, not only has the trend failed to reverse, but to the contrary, it has gained in strength. From the trivialization of social justice, we have moved to the radical inversion of the values that undergirded European societies since World War II, allowing the tide of historiographic and political revisionism to conclude with ease the demolition of Marxist, and more generally critical, historiography. This was all the more effective since the new media individualizes memory and renders it more intimate, “in an apparent pluralism that has the same effects as a rigid ideological monopoly,” captured by Paul Virilio in the term “globalitarianism.”13

The French publishing world is today flooded with countless books that, to great media fanfare, promise to completely overhaul our understanding of European society in the last forty years, with the prime culprit now the so-called cultural hegemony of the left, supposedly unbroken since 1968, and the root of all ills. These books castigate a period “completely defined by May 1968,” in which they find nothing but malaise and the “defeat of thought,”14 a period that saw the loss of the “true values” of national identity, undermined by the “triumphant internationalism” advocated by the left and in particular by the radical left. To this is added the stigmatization of immigrants, foreigners, and those with family or religious roots in formerly colonized countries.15 As one would guess, Muslims are in particular singled out for public opprobrium.

The writers of these books pretend to be bravely pronouncing long-denied, yet self-evident, truths. One is Eric Zemmour, columnist and polemicist for Le Figaro, the daily of the institutional French right, who wrote a book titled The French Suicide; another is writer Michel Houellebecq, a regular on the French talk-show circuit with a taste for provocation, whose novel Submission (in which a Muslim fraternity candidate beats the National Front’s Marine Le Pen in a presidential election) came out just as the Charlie Hebdo massacre took place; finally, there is Phillippe Val, managing editor at Charlie Hebdo between 1992 and 2009, whose book Malaise amidst Boorishness (attributing, among other things, the origins of Stalinism to Rousseau) came out in April 2015.16 As noted by French political journalist Edwy Plenel, these authors have mastered the art of sublimating “self-hatred paved with unhappy identity, of French suicide or imaginary submission, laced with acrimony, bitterness, and resentment.”17

It is as if the reversal of the balance of forces on the economic and social plains correlates to an inversion of values, and increasingly so, as the conditions of life and work of a growing part of the European population degrade (with a growing gap between rich and poor, ever-rising unemployment, and austerity measures attacking the fundamental rights of retirement, health, and education) and as the “moral crisis” and “ideological confusion of the dominant class” deepens with every additional failure of their reforms purporting to end the crisis and restart the economy.18 The advance of this inversion of values is made easier by the absence of a horizon of social transformation in a world that “no longer has any kind of stability; it is shifting, straddling, gliding away all the time.”19 It is also the reflection of the attractiveness of a new right-wing constellation, identified by Guido Caldiron as the “plural right,”20 which manifests itself in the ever-expanding room for the cultural and political interventions of the extreme right. Enzo Traverso, the Italian historian of the holocaust and totalitarianism, speaks of the “porous border” between the institutional right and the extreme right.21

All over the world, this plural right has managed over the last ten years to place its flagship themes at the center of the political debates—chief among them immigration, which remains its primary unifying principle. But it was also able to seize what the Argentine political theorist Ernesto Laclau called “empty signifiers”—such as liberty, equality, universalism—and infuse them with its own political grammar, turning them into a “potent weapon of ideological hegemony.”22 On the eve of France’s regional elections of March 2015, French philosopher Jacques Rancières gave a bitter account of the phenomenon:

[The principle of] universalism has been confiscated and manipulated. Having been made into the distinctive sign of one group, it points an accusatory finger at a precise community. … All the republican, socialist, revolutionary, and progressive ideals have been turned against themselves. They have become the opposite of what they were supposed to be: instead of weapons in the struggle for equality, they have become tools of discrimination, contempt, and separation against a people viewed as backward and stupid.23

A Specter Is Haunting Europe:

The National-Populist Constellation

Since the last European elections, the forces of the radical right are the center of attention and a source of concern. The French sociologists Luc Boltansky and Arnauld Esquerre even speak of a “great fear,” worrying that “a Right that is dazed and pulled toward fascism by its extremes is in complete control of the situation.”24

Indeed, the latest electoral achievements of the right give goose bumps: in the UK, UKIP received 27.5 percent of votes (against 16.1 percent in 2009); the Party of the People of Denmark, 26.7 percent (14.8 percent in 2009); Alternative for Germany, 7 percent; the Austrian People’s Party, 19.7 percent (12.7 percent in 2009); the Swedish Democrats, 9.7 percent (3.3 percent in 2009). The Finnish True Finns lost ground, receiving only 12.9 percent of the votes for the European Parliament, against 14 percent in 2009; but in the legislative elections of April 2015 they became the second largest party with 17.6 percent of the vote and 38 seats in the Parliament—in their own words, they “are here to stay.”25 The openly fascist parties at the European periphery received 9.4 percent of the suffrage in Greece (Golden Dawn) and 14.7 percent in Hungary (Jobbik).

The earthquake seems all the more significant in France, where, under Marine le Pen’s leadership, the makeover of the FN, which has national reach and aspirations, looks successful on the face of it. The success of the party in the European elections of June 2014 was indeed confirmed in the regionals in March 2015, when the FN emerged as the third largest party in France—the new byword of the situation is “tripartism.” Although the FN is not (yet) in a position to assume power nationally, its goal of achieving a national electoral base is advancing apace. The party has succeeded in implanting itself in places that were considered immune to its discourse, including some affluent areas.26 This is an important development, especially if—as political scientist Joel Gombin argues—support for the FN is undergoing “stabilization, even stagnation in the most rural, lower-class, and peripheral areas,” against significant growth in “a number of more affluent, urban, and suburban areas.”27

As the electoral success of the FN and its ever-growing nationwide reach in France attests, the nationalist-populist constellation is putting down strong roots in the European soil. The extreme right is no longer a marginal, nostalgic affair. In this sense, it can no longer be described as a remnant of postwar neofascism, a framing that has been quite convenient for the parties in government, allowing the Socialists to evade criticism of their politics that have effectively killed the left, and allowing the right to ever more openly integrate the political grammar of the extreme right in its discourse and practice. Moreover, while some of these extreme-right parties have until recently worn their fascist lineage on their sleeves, others have taken their distance from it publicly in order to win votes and build a national base—with varying degrees of success. The first to do it, although in the long run unsuccessfully, was the Italian Gianfranco Fini, who turned the openly fascist Social Movement into the Alleanza Nationale in 1995. In Hungary, Jobbik, which Marine le Pen’s FN considers beyond the pale, seems to have followed the same trajectory, in particular by toning down its anti-Semitic and racist themes in order to win the votes of disenchanted conservatives.28

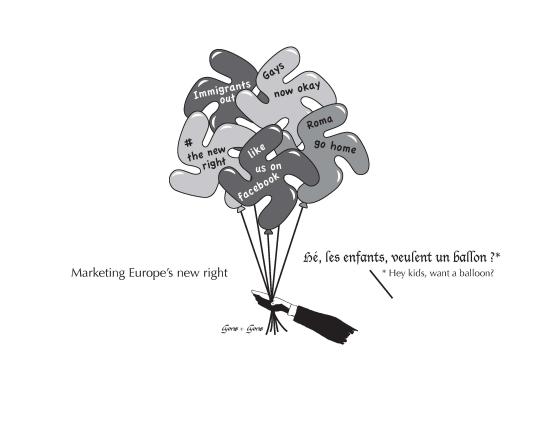

This new, “de-fascisized” extreme right clearly belongs to the twenty-first century. Whether nationalist or ferociously regionalist, like the Northern League in Italy, it wants to be resolutely modern, to the point that some even associate it with hipsterism. As French political scientist Jean-Yves Camus rightfully noted, it has traded the cult of the state for a neoliberal perspective that advocates economic deregulation, reducing taxes for corporations, and the respect of individual liberties,29 and defends private property and free enterprise. The new extreme right is, however, strongly Europhobic, seeing in the project of European integration “a socialist plot, concocted by Eurocrats who live at the expense of small business, [and] encourage immigration and the welfare state.”30 This right exalts “the people” and bases its attitude toward politics on the need to “purify” the political scene of a political “caste” perceived as corrupt.

The European extreme right embodies the rejection of the politics of austerity. It advocates an exit from the Euro as means of stimulating the domestic economy. It fights against the “Islamization” of a West threatened by “the clash of civilizations,” at times, however, raising the banner of women’s rights and even the rights of homosexuals, thus blurring the lines of demarcation between it and the institutional left (Pim Fortuyn, assassinated in 2002, had paved the way in the Netherlands). Its common political objectives, however, openly advertised, are essentially limited to the destruction of the welfare state, anti-Marxism, violent racism—in particular against immigrants, “the heirs of the nineteenth century’s dangerous classes,”31 and above all against Muslims and the Roma people—the defense of patriarchy and imperialism, and the stigmatization of the poor, foreigners, the unproductive, and sexual minorities. Thus, for example, during a televised debate with the Italian anti-globalization organization No Global, the new leader of the Northern League, Matteo Salvini, said that “once I’m done with the Roma, I’ll take up the social centers.”32

In most countries, these far-right parties reflect the loss of confidence, not only in European institutions, but above all in the political forces that drive them. It is an “anti-system” vote that rallies the petty- and middle-bourgeoisie (doctors, teachers, small businesspeople), but also has a significant following among the lower classes (workers, public employees, and the unemployed) and may also, as in the case of the French National Front, attract young people. The extreme right benefits from the left’s state of fragmentation as well as from the corruption scandals that shake parties in government almost everywhere in Europe, from Italy to France, Spain, and the UK. In France, the demobilization of the electoral base of not only the institutional left, but also, for different reasons, the anti-neoliberal—including the anti-capitalist—left, and the dynamics of voting on the right that keep favoring the FN, seem to confirm a sociopolitical decomposition of the so-called “left-wing nation,” the outcome of the disorientation and the growing despair spreading through the world of work and the less affluent neighborhoods in the context of a generalized political and social crisis.

The extreme right presents itself in this vacuum as the only possible alternative, nibbling at the popular electoral base of conservative parties, but also affecting the traditional base of the socialists, thus pushing the parties in government to adopt their rhetoric and follow suit, in particular when it comes to immigration restrictions and national security. What has been defined as right-wing populism thus manifests itself also as “anti-popular-state populism.”33

It is evidently tempting to read in the electoral successes of the radical right merely the political impact of an economic crisis that, since 2007, continues unacknowledged. However, this economic and social crisis coincided with a political and cultural crisis that has shaken the political and social field and the balance of forces inside European societies for the full length of the last three decades. The extreme-right tide is in this context only the crisis’s tip of the iceberg, its distorted and deformed appearance. What we must therefore rethink in order to give a political sense to the future is not so much our ability to defend what is left of our social rights, but our ability to call into question the full social order, a civilizational system that can no longer hold.

Yet the challenge we face today lies precisely in that kind of crisis in which, in Antonio Gramsci’s words, “the old is dying and the new cannot be born.” The next conference of Historical Materialism, scheduled for November, will be aptly dedicated to this very question (www.historicalmaterialism.org). We are most likely passing through the tail of the comet of the slow political, social, and economic transformation that European societies have undergone since the 1980s. The new political and social configurations that will have emerged from this seismic mutation are not yet identifiable. But there is no inevitability in the emergence of a new order, within which this extreme right that is ascendant across Europe would play an as yet undefined role in the social conflict. The only certainty is that the old paths of liberation are coming apart beneath us.

It has been ten years since the U.S. billionaire Warren Buffet declared the victory of the rich in the class war. It is undoubtedly true that the first big battles have been won by the 1 percent at the expense of the 99 percent. But the struggle is far from over, and its outcome is in our hands. It rests with our capacity to reimagine liberation together in the twenty-first century, to delineate a world capable of responding to the fundamental needs of society, democratically decided, in a way that respects ecological balances. We also need strategies that fully empower “the immense multitude that is unaware of its own strength” (Louise Michel), and modes of organization that reconcile individual initiative, and the federation of energies, with their centralization. Only then can we fight against “the skepticism with regards to all theories and general formulae” that characterizes our age.34

Footnotes

1. See Cinzia Arruzza, “The European Conundrum,” Jacobin, May 2014, www.jacobinmag.com; Stéfanie Prezioso, “The European Elections: Despite the Crisis the Neoliberals Save the Day,” New Politics, newpol.org. Also Jean Batou, “Is 21st Century Fascism Advancing Undercover?” newpol.org.

2. Stuart Hall, “Brave New World,” Marxism Today (October 1988), 24-29.

3. Angelo Tasca, Naissance du fascisme. L’Italie de 1918 à 1922 (Paris: Gallimard, 1938).

4. Frederick Lordon, Jusqu’à quand? Pour en finir avec les crises financières (Paris: Raisons d’agir, 2008).

5. Luciano Gallino, La lotta di classe dopo la lotta di classe. Intervista a cura di Paola Borgna (Bari: Laterza, 2012), 3-4.

6. Ben Stein, “In Class Warfare, Guess Which Class is Winning,” New York Times, November 26, 2006.

7. Jean-Pierre Durand, La Chaîne invisible. Travailler aujourd’hui: flux tendus et servitude volontaire (Paris: Seuil, 2004).

8. This is what François Sabado noted with sadness at the Izquierda Anticapitalista Congress, January 17-18, 2015, see Europe Solidaire here.

9. Stuart Hall, “Thatchers Lessons,” Marxism Today (March 1988), 20-27; Stuart Hall, “Brave New World,” Marxism Today (October 1988), 28.

10. Hall, Thatcher’s Lessons.

11. Lenin, “Letters from Afar. The first Stage of the First Revolution,” March 1, 1917 (published March 20-21, 1917 in the Pravda). Cited in Stuart Hall, “The Great Moving Right Show,” Marxism Today (January 1979), 14. See also Hall, “Brave New World,” 24.

12. Frederic Jameson, “Future City,” New Left Review (vol. 21, May-June 2003), 76.

13. John Armitage, ed., Paul Virilio. From Modernism to Hypermodernism and Beyond (London: Sage, 2000), 48.

14. Eric Zemmour, Le suicide français (Paris: Albin Michel, 2014), 9.

15. Edwy Plenel, “L’idéologie meurtrière d’Eric Zemmour,” Médiapart, January 5, 2015.

16. Michel Houellebecq, Soumission (Paris: Flammarion, 2015); Philippe Val, Malaise dans l’inculture (Paris: Grasset, 2014).

17. Edwy Plenel, “Lettre à la France,” Médiapart, January 20, 2015.

18. Cédric Durand, “Fatigue du capitalisme et résistance sociale,” Contretemps-web, 2010.

19. J. Armitage, ed., Paul Virilio.

20. Guido Caldiron, La destra plurale. Dalla preferenza nazionale alla tolleranza zero (Roma: Manifestolibri, 2001), 9.

21. Enzo Traverso, “ L’islamophobie est la source du nouveau populisme de droite,” Libération, January 5, 2011.

22. Ernesto Laclau, “Why do empty signifiers matter to politics? (1994),” in David Howarth, ed., Ernesto Laclau. Post-Marxism, populism and critique (London, New York: Routledge, 2015), 167.

23. Jacques Rancières, “Les idéaux républicains sont devenus des armes de discrimination et de mépris,” L’Obs, April 4, 2015.

24. Luc Boltanski and Arnaud Esquerre, Vers l’extrême droite. Extension des domaines de la droite (Paris: Editions Dehors, 2014), 11, 13.

25. Jean-Baptiste Chastan, “Les centristes remportent les législatives en Finlande,” Le Monde, April 19, 2015.

26. Fabien Escalona, “Sur les ruines de la politique émerge un nouvel ordre electoral,” Médiapart, March 24, 2015.

27. Joël Gombin, “Le FN perce dans de nouveaux territoires,” Le Monde, March 24, 2015.

28. Andrew Byrne, “By-election win marks breakthrough for Hungary’s far-right Jobbik,” Financial Times, April 13, 2015.

29. Jean-Yves Camus, “Du fascisme au national-populisme. Métamorphoses de l’extrême droite en Europe,” Le Monde Diplomatique (May 2002).

30. Richard Seymour, “Taking on the ‘fruitcakes’: How can we stop UKIP?” Red Pepper, September 7, 2013.

31. Enzo Traverso, “La fabrique de la haine: xénophobie et racisme en Europe,” Contretemps, April 17, 2011 (contretemps.eu); Alberto Burgio, Nonostante Auschwitz. Il “ ritorno” del razzismo in Europ (Roma: Derive Approdi, 2010).

32. Il Fatto quotidiano, April 10, 2015.

33. Guillaume Sibertin-Blanc, “Du simulacre démocratique à la fabulation du peuple: Le populisme minoritaire,” Actuel Marx (vol.2, no. 54, 2013), 71-85.

34. Antonio Gramsci, “‘Wave of Materialism’ and ‘Crisis of Authority’,” in A. Gramsci, Selections from Prison Notebooks (London: ElecBook, 1999), 556.

interesting

hm..

interesting

Hmm…