“¿Qué Nueva, Qué Nueva, Qué Nueva Mayoría? ¡Si van a gobernar pa’ la misma minoría!” (“What New Majority? They’ll rule for the same old minority!”)

“¿Qué Nueva, Qué Nueva, Qué Nueva Mayoría? ¡Si van a gobernar pa’ la misma minoría!” (“What New Majority? They’ll rule for the same old minority!”)

FEL student demonstrators

Last year Socialist Michelle Bachelet reclaimed the presidency after four years of center-right rule and restored power to the Concertación coalition that had governed Chile since redemocratization. For progressives, and even some radicals, this election opens a period of heretofore elusive popular reforms. They claim that a recent movement upsurge has supplied the necessary steam to complete the transition to democracy that Chile’s center-left has thus far been unable to accomplish. Spurred by rising mobilization under the outgoing government, and by student activists now in Congress, Bachelet’s landslide victory is said to offer the momentum to carry out the widely demanded tax, constitutional, and education reforms on which she campaigned. With the Pinochetist Alianza’s backing at historic lows and an expanded reform bloc, now christened Nueva Mayoría (NM, New Majority), and bolstered by the rise of a new generation of young Communists who headed massive 2011-2012 student mobilizations, the prospects for pushing through changes benefitting workers, students, and the rural and urban poor appear well founded.

There is no question that Chile’s workers and poor are better positioned today than they were just ten, to say nothing of twenty, years ago. Indeed, popular forces for change enjoy the most auspicious balance of forces since the 1973 coup that stamped out Chile’s democratic road to socialism. To obtain, however, a firmer grasp on what these elections mean for neoliberalism’s continuity and prospects for emancipatory politics in Chile, it is worth closely examining their results in relation to elite interests and movement strategies.

Historical Context

The elections and new movements must be placed within a longer view of Chilean history. Developments going back a century have shaped the current conjuncture. First, the country’s economic conditions generated a process of class formation that produced a socialist workers movement and Marxist-led, independent radical unions in the early twentieth century. Workers looked to the Communist (PCCh) and Socialist (PS) parties to guide their struggles against employers and the state. Rising class conflict converged with the failure of postwar developmentalist governments and the activation of students, peasants, and the urban poor, culminating in the election of Socialist Salvador Allende in 1970. Taking advantage of elite divisions, Allende’s Unidad Popular (UP, Popular Unity) coalition, led by the PCCh and the PS, pursued an improbable socialist transformation without institutional rupture. Meanwhile, new left forces engendered by erupting movements, notably the insurrectionist Movimiento de Izquierda Revolucionaria (MIR, Revolutionary Left Movement), challenged the UP from the left, widening a revolution-from-above versus revolution-from-below rift in Chile’s road to socialism.

By contrast, elites reunited, instigating the 1973 coup that wiped out a generation of militants and their organizations. Reaction to the Popular Unity experience has also severely shaped the present. The junta under General Pinochet ushered in a radical neoliberal capitalist transformation of Chilean society through the barrel of the gun. With the MIR physically eliminated, the PS in exile, and the PCCh tortured, disappeared, and scattered, Pinochet’s military regime installed neoliberal orthodoxy enshrined in the 1980 authoritarian constitution. It outlawed the left and rigged future electoral rules in favor of minority right-wing elites. The junta’s laws disempowered unions, deregulated markets, and recommodified social goods like land, health care, pensions, and education. Indeed, one of Pinochet’s final decrees formalized the prevailing privatization of education by decentralizing schools’ administration and funding, and establishing a voucher system that transferred public money to low-quality venture schools.

Despite pro-market mythologies, the crises and hardships caused by savage market reform triggered mass mobilizations during the early to mid-1980s. Under popular pressure, the regime was forced to consider a return to democracy. To secure a managed transition, elites, supported by the United States, brokered a deal in which free elections would be granted in return for the domesticated opposition accepting free-market reign and deactivating movements. With the MIR all but extinct and the PCCh marginalized, the renovated market-socialists of the PS joined their former foes, the Christian Democrats (DC, Democracia Cristiana) to lead the center-left coalition that governed from 1990 to 2010. Two decades of Concertación rule amounted to a neoliberal democratic regime that undermined popular participation, left Pinochet’s charter unchallenged, and harshly repressed any sign of protest. Able to secure majorities while promoting elite interests, the center-left consistently beat out the hard-right neoliberal Alianza coalition. Four successive DC-PS governments deepened Pinochet’s privatization project, maintained labor’s disenfranchisement, and preserved the highest level of inequality among OECD countries. Unsurprisingly, growing inequality and oligarchic rule fostered new mass movements with expanding and deepening grievances. The 2005-2006 high school rebellion against Bachelet’s first government was a watershed signaling a qualitative leap in popular mobilization. Frustration with the Concertación set the scene for the right’s presidential victory in 2010.

Progressive Optimism

The optimistic scenario anticipated by left analysts celebrating Bachelet’s second election presents another near epochal shift in Chile’s polity. This perceived realignment is said to be driven by the irreversible decline of the hard right. After competing steadily with the Concertación since redemocratization and finally surpassing its historic 40-45 percent threshold to win the presidency in 2010 second-round elections, the Alianza’s ability to rule seems buried for the time being. Progressives in Chile are savoring a “once you go right, you’ll ALWAYS go back” moment. This unprecedented rejection allegedly clears the way for a revival of Allende’s dream of true political and economic democracy.

This sanguine scenario is reinforced by the undeniable influence of emerging mass movements credited with pushing the dominant electoral bloc as well as the national policy agenda unequivocally to the left. As wider swaths of non-elites reject market orthodoxy and increasingly identify with mounting protest, a period-defining shift in public opinion appears to be taking hold before our eyes. The young Communists, including iconic Camila Vallejo, former spokesperson for the university student union confederation (CONFECH), and their allies who led 2011-2012 protests that shook the foundations of Chile’s neoliberal model after years of quiescence, have been elected to Congress. Their parent party has finally realized a long-sought gambit to enter the center-left coalition and “pressure from within.” As Vallejo, who once vowed never to campaign for Bachelet, put it in December, “The elections give us a majority that allows us to make structural changes. Social movements are pressuring many sectors that were not in favor of change before and that have now changed their mind.”

This sanguine scenario is reinforced by the undeniable influence of emerging mass movements credited with pushing the dominant electoral bloc as well as the national policy agenda unequivocally to the left. As wider swaths of non-elites reject market orthodoxy and increasingly identify with mounting protest, a period-defining shift in public opinion appears to be taking hold before our eyes. The young Communists, including iconic Camila Vallejo, former spokesperson for the university student union confederation (CONFECH), and their allies who led 2011-2012 protests that shook the foundations of Chile’s neoliberal model after years of quiescence, have been elected to Congress. Their parent party has finally realized a long-sought gambit to enter the center-left coalition and “pressure from within.” As Vallejo, who once vowed never to campaign for Bachelet, put it in December, “The elections give us a majority that allows us to make structural changes. Social movements are pressuring many sectors that were not in favor of change before and that have now changed their mind.”

With favorable street sentiment and parliamentarians agitating in Congress, the general feeling is that the core features of NM’s platform—tax, education, and constitutional reforms (including changes to the restrictive binomial electoral scheme)—are nearly certain. Further, progressives in this culturally conservative society feel well-positioned to expand “social” rights including gay marriage, gender identity protections, and even “therapeutic” abortion.

Even some radical autonomists advance the notion that Bachelet’s inauguration is the culmination of decades of democratic struggle from below. A piece appearing in Upsidedownworld.org holds, “Bachelet’s return to the presidency, and her promise for structural changes to Chile’s educational and political system, is the result of a decades-long struggle to move out of the shadow of the Pinochet dictatorship, and is one of the fruits of the more recent student movement for a better society. … The student movement’s pressure for change helped pave the way to Bachelet’s re-election and formed the backbone of what became key promises on her campaign trail.”

Describing the new radical impulse overtaking Chile’s polity, the Guardian summed it up thus: “The [student] rebellion that exploded in Santiago in 2011 is not simply against this or that policy. … A more profound [wave of leftism] is beginning [and] spells the end of the dogma that the economy determines people’s consent rather than the other way around. It is the time of the people once again.”

Sensible Sanguinity?

On election night, as the progressive left was celebrating early results, Bachelet’s campaign was far from euphoric. Fewer than 100 supporters showed up to the rented space to cheer her December victory speech as they cagily bobbed to generously amplified cumbias. Meanwhile, a new “wave of leftism” had occupied her campaign headquarters as high school students who had called for annulling votes took direct action to repudiate the bipartisan consensus on profit-driven education.1 Newly elected National University Federation (FECh) president, Melissa Sepúlveda, showed up to lend her support, warning against “taking up the movement’s slogans yet filling your mouths with empty promises!” In response to Young Communist reversal and subsequent stumping for Bachelet, the campus militants who succeeded Vallejo in the 2012 FECh elections put what they view as the Concertación’s dead-end elite politics more colorfully: “The Concertación is the Titanic, and we will not buy tickets on the Titanic, and we feel nobody should buy tickets there.”2

What was happening? How could the very movements deemed to be supporting the democratic aspirations of Chile’s center-left be using their tested disruptive tactics to frontally clash with the Concertación and its new Communist Youth allies, themselves spawned by the movements? How could the very forces that finally put reform on the national agenda after 20 years of stringent neoliberal democracy offer such a radically different read of the moment?

In fact, the analysis of the disparagingly nicknamed ultras is not so different from the strategic understanding of Concertación oligarchs. The brokers of Chilean neoliberalism that emerged from the transition candidly view the moment as a chance to restrict changes to post-Pinochet rules of the game. As Sergio Bitar, a top-level coalition operative put it, “We need to negotiate with the right like we did when we negotiated an end to [minor features of Pinochet-imposed restricted democracy]. That negotiation lasted fifteen years; [the right] is very closed-minded and if they want to prolong things this time, they will make the country explode. We therefore have to understand that change within our institutionality is better than change from outside our institutions”3 (emphasis added).

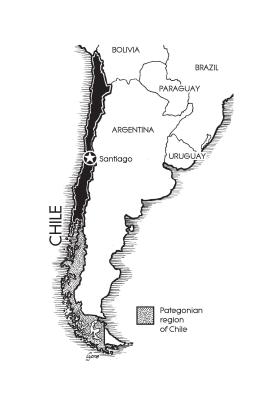

Like the regime managers they are confronting, the new radical forces understood a basic fact of these elections. Chile was deciding on far more than its next political authorities: the country’s convulsed political and social forces are assessing the magnitude of the reforms needed to change the post-authoritarian regime and the role that growing movements should play in achieving them. Besides the massive student protests that mobilized throughout 2011 and 2012,4 so-called regionalist movements have erupted, including a Patagonian mini-commune confronting special forces of Chile’s militarized police for days;5 environmentalists who led street rebellions to challenge mining and hydroelectric projects enjoying the green light of both electoral blocs;6 shanty mortgage debtors organizing and making class demands; and Mapuche indigenous communities’ struggling against national oppression in what can only be called a low-intensity counterinsurgency war by the state.7

The new radicals reject narratives of democratic culmination and shared goals. The elections, in their view, concealed the true contest between those seeking to expand independent class capacities and those who aim to dissolve them under prolonged democratic neoliberalism. The two groups base their strategies on clashing premises: in broad terms, the latter argue that Chile’s fragile democracy needs to overcome fetters imposed by the dictatorship to address inequality; the former, by contrast, are focused on toppling the regime itself. Hence, whereas the latter pitch inescapable policy changes as the culmination of a coherent and linear drive to address institutional vestiges of military rule, for the former the existing form of democracy is itself the central problem. Moreover, they warn that the ballot outcome shows the regime has dangerously retaken the initiative after mass mobilizations had it on the ropes. In this sense, partisan elites are correct to view the recent movement upsurge as a threatening tsunami rather than a friendly tide. The emerging battle then is over whether reform should stabilize the democratic neoliberal regime or whether movements can supersede it. It will determine who sets the terms and who emerges bolstered for a deeper and longer fight.

Behind the Numbers

Prior to any sensible adjudication between these rival perspectives, a review of the results is in order. An analysis of the vote reveals that while there are reasons for optimism in both camps, pitfalls abound.

Any breakdown necessarily begins with a look at turnout. Despite the momentum of the recent upsurge, 50 percent first-round abstention should give pause to all left forces. As I argued in a recent piece,8 U.S.-level turnout is less the result of newfound disappointment or apathy than the recently acquired ability to lawfully sit out elections. Cutting both ways, such middling participation levels reflect the large chunks of Chilean society defeated by neoliberal exclusion as well as newly activated layers looking for options beyond current partisan offerings.

The next observation, which has eluded many, involves the fortunes of the major blocs: together, the Alianza and former Concertación received over five-sixths of all votes. Given the “top-two-winners-take-all” binomial system, together they grabbed 96 percent of House seats and 100 percent of Senate posts. As is widely understood, electoral rules guarantee the two dominant blocs roughly equal shares of seats. In fact, since coalitions are all but ensured to win district representation, often candidates don’t compete against “opposing” parties, instead fighting their partners for each bloc’s reserved spot.9 Further, despite the Alianza’s poor showing in the presidential race, legislative results are perfectly consistent with their tallies since redemocratization—40 percent in the lower house ballot compared to 43 percent in 2009 and 39 percent in 2005. So even while a leading consultant for the hard-Pinochetist wing of the Alianza lamented that “in the last few years the right has suffered a powerful cultural defeat,”10 the right coalition remains a solid pillar of the regime.

Concretely, this translates into a 21 to 17 advantage in the Senate and a 67 to 49 edge for the center-left in the lower house. In effect, although the Communist votes shifted the center of partisan gravity slightly to the left, the duopoly that has shared power since 1990 remains intact. Not only do results suggest that the pro-Pinochet right is far from buried, more specifically they cast doubt on Nueva Mayoría’s ability to deliver on its promises. If the powerful right-wing of the bloc cooperates, Bachelet may muster the simple majority needed to pass tax reform. Her coalition, however, missed the mark for educational reform and constitutional amendments.11

Still, the inclusion of the PCCh in Nueva Mayoría should not be derided outright. After all, there is a reason the Concertación resisted Communist advances for twenty years. Though PCCh president Guillermo Teillier raced to the front of the class to diligently announce that Communists will not “make waves” against Bachelet’s second tenure, the party’s ability to discipline its new blood is no foregone conclusion.

Besides Vallejo who led her district balloting with 44 percent, her co-thinker Karol Cariola, a former leader of the historically radical University of Concepción students—who was less hyped—also won handily with 38 percent of votes. Further, the head of new and theoretically independent Revolución Democrática, a former CONFECH co-spokesperson and president of traditionally conservative Catholic University students, Giorgio Jackson, won his district with a resounding 48 percent of votes cast.12 Though Vallejo and Cariola—as well as rookie Daniel Nuñez—have never displayed the independence of other members of PCCh’s new generation (such as copper federation leader Cristián Cuevas), their party loyalty doesn’t make them outright fools. They know why people voted for them, their instincts having been sensitized during their time at the head of the student insurgency. And while it’s true Vallejo has broken her vow to never support Bachelet, it remains to be seen whether she drops her pledge to use the legislative tribune to stimulate pressure from below.

A third student leader facing no such dilemmas is Gabriel Boric of the recently formed Izquierda Autónoma (IA) or Autonomous Left. Though independent left forces garnered roughly 7 percent of the vote, Boric will be their only legislator. IA rose to prominence on campuses after students rebuked FECh leadership for supporting a Concertación–mediated truce to the educational conflict.13 Right when the international press was trumpeting Vallejo, Boric was defeating her in the election for FECh president on a platform that emphasized strengthening militant and autonomous grass-roots movements. Over a year later, demonstrating that independence from Nueva Mayoría might be an asset rather than a liability, Boric came in first in his Patagonian district, ahead of establishment parties.

Reforms … and Reforms

With the electoral balance of forces thus arrayed, the ineludible reform agenda will be taken up in a tightly scripted yet contested way. Bachelet and Nueva Mayoría will aim to satisfy its business patrons as well as non-elite supporters by “responsibly” delivering the highest attainable results.14 Business, meanwhile, will look to approve the mildest possible reforms functional to the regime’s recovery and stable reproduction. Without question, there will be real tactical disputes over this range. The PCCh will use its minor influence to push in one direction, all the while struggling to define its position in relation to reforms that will undoubtedly disappoint its constituents. Finally, the new radical forces will push to deepen proposed policies, trying to defeat restrictive reforms but doing so in ways that strengthen rather than demoralize new movement actors.

Nueva Mayoría’s anchor policy is tax reform. Not only is this the most achievable measure, it is the means to addressing the most decisive issue of the moment: education reform. In truth, there will be few serious challenges to raising corporate taxes to somewhere around the 25 percent on which Bachelet ran. Under her right predecessor, billionaire Sebastián Piñera, corporate taxes were raised with elite sanction in the aftermath of the 2010 earthquake to cover unexpected infrastructure and welfare expenditures. Today, business understands that political tremors also require a slight tightening of the profit spigot. Indeed, as banking’s serene response to the unveiling of Bachelet’s program revealed, of all the proposed reforms, this is the one that rankles least. Encouraged there were no “surprises,” JP Morgan gave its thumbs-up.15 Adding its seal of approval Morgan Stanley expressed “certainty that Chile’s basic political framework is not at risk, including fiscal discipline.”16 Three years ago, increased corporate taxes were followed by the upsurge in struggle. This time around, business, frustrated by its lose-lose situation under the Alianza, is hoping a broader center-left offers more compelling reforms that contain rising popular demands.17

Bachelet intends to crown her accomplishments by finally delivering a new, grandiose educational model. Contrasting her success with Piñera’s dysfunction on this front, she will present Nueva Mayoría as the only political force capable of overhauling the system inherited from the dictatorship. Yet, beyond promising expanded free options, Bachelet has offered vagueries around increasing accessibility and gradual reduction of the primary and secondary school voucher system. Once more, no elite feathers have been ruffled. New student leaders, on the other hand, have chastised the Concertación for not breaking altogether with the logic of neoliberal education. The core demand of the student movement is renationalization of education, top to bottom—scrapping inequitable decentralization, vouchers, private management and ownership of schools and universities whether non-profit or not, and tuition and fees altogether. Recently, FECh’s Sepulveda harshly rejected Bachelet’s reform preview, which, taking a page from Piñera’s World Bank-inspired discourse, contemplates individual repayment of tuition costs following gainful employment.

A better test of Nueva Mayoría’s willingness to push the envelope involves shelved proposals for labor market reform. Though the PCCh-led national labor confederation (Central Unitaria de Trabajadores or CUT) demanded concrete measures that would reverse Pinochet’s obliteration of labor rights, including restoration of industry-wide bargaining, it is apparent that Bachelet will do little of substance to enhance unions’ fragmented negotiating power. Paying lip service to CUT’s other top demand for renationalized pensions, NM dangled the consolation prize of an Obama-like public option aimed at “stimulating competition” with funds privatized under dictatorship. Despite disparagement of labor grievances, CUT dutifully applauded Bachelet’s celebration of union “support for our program which represents Chile’s workers.”18 Undeterred by Bachelet’s nixing of labor’s central demand, CUT president Bárbara Figueroa formalized PCCh endorsement of this unequal exchange by proclaiming a partnership with the future administration. She averred that pro-labor “reforms will only be possible if we win the December 15 [runoff].” This raw deal for workers can only be explained by Bachelet’s other key trade-off: business would sagaciously approve tax and education reforms as long as NM refrained from tampering with Chile’s flexible labor markets, the cornerstone of its neoliberal orthodoxy.19

Our Mobilizations and Their Moves

The surest way for NM to deliver, of course, would be through a constitutional makeover that would guarantee the legislative majorities required for reforms. The first step would be dumping the binomial system. Yet, surprisingly, in a recent lower house vote to eliminate its constitutional basis, the ignominious amarra or “mooring” imposed by Pinochet’s 1980 charter, dozens of Concertación no-shows guaranteed that the quorum went unmet.20

While NM would numerically benefit from dispensing with the binomial system, the measure’s net gains are less certain for the coalition. Left forces would be the biggest beneficiaries, to the detriment of the exclusionary regime from which the Concertación has profited most. As a recent leak by Alianza president Patricio Melero revealed, Socialist and DC chiefs have confided concern that a poor electoral showing by the right would weaken valued counterweights to demands from the left both within and outside the bloc.21 Concertación oligarchs are foremost committed to the restrictive bipartisanship that undergirds their political reproduction. Accordingly NM roundly and publicly rejects the PCCh-promoted Constituent Assembly preferring to stick to existing procedural rules allowing only the faintest modifications to current schemes of representation.22

Still, to ensure political success, Nueva Mayoría has real interest in achieving reforms. To that end, Communists, and even progressive Concertacionistas, not only appreciate the value of grass-roots pressure, but may even promote mobilizations to win elite-approved policies and safely channel the upsurge. But with independent forces on the move, calling people onto the streets for narrow political gain carries daunting risks, especially with the right appearing to be in disarray. Put simply, it may give insurgents opportunities to protest without the ability to contain them. If NM fails to act and appears ineffectual, however, the coalition will pay an incalculable price and the regime’s legitimacy will continue to dissolve. Its aim then is to get ahead of any mobilizations and push through uncontentious reforms, taking advantage of the elections’ momentum to display quick results.

The PCCh finds itself in a particularly tough spot. If, as expected, NM policies disregard movement demands, Vallejo and her ilk just may follow the party script. The real uncertainty revolves around the more dynamic interplay between less disciplined activists and the mobilized bases who refuse to accept parliamentary success as an end in itself. Just as new student cohorts abandoned the Communist Youth, groups under PCCh influence, particularly in the labor movement, could turn to more independent and radical tactics and goals. Actions by cadre like Cristián Cuevas, who emerged as an activist leader of outsourced service workers to head the entire copper workers confederation, will have to be followed closely in this scenario. While still formally committed to the PCCh strategy, Cuevas, who was edged out by comrade Figueroa in questioned CUT elections, best exemplifies the disruptive new movements of class segments excluded by regime institutions. He has consistently opposed flexibilization and championed sectoral bargaining, the very policy that Bachelet removed from the agenda. Party activists like him will now find it hard to act as firemen extinguishing the conflagrations they helped light against Concertación orthodoxy. The coming months and years will witness a dispute within NM, and more precisely within the PCCh, which will centrally impact the broader struggle between regime maneuvers and counter-regime movements.

Perhaps most decisive will be how radicals respond to NM’s opening salvo. Their tactics, for one, will condition the decisions of disgruntled Communists. More generally, this new, new left will concentrate its energies on reactivating the student movement and expanding mass popular defiance to pressure for more transformative reforms. Grasping the inherent limitations in student capacities, this diverse array of independent revolutionaries shares a commitment to building a broader insurgent force that centrally involves workers, their communities, and their organizations. They seek to strengthen the preliminary alliances woven at the height of the 2011 mobilizations and expand the organized forces pressing for change outside of the institutionalized rules of the game. In so doing, they look to expose the regime’s duopolistic character as the main barrier to political and economic democratization. In short, they hope that the steam mustered for more egalitarian and emancipatory policies overwhelms the regime altogether.

A major obstacle, perhaps unsurprisingly, is disagreement among new autonomous left forces. The very reason that the Autonomous Left (IA) and Boric, after ushering out the Young Communists, were displaced from FECh leadership by Sepulveda is an ostensible “strategic difference” that threatens coherent radical action. IA favors consolidating the student movement as the period’s most advanced anti-regime contingent, while simultaneously building a genuine dissident presence within state institutions.23 Boric’s first-place finish demonstrates that in the context of rising struggle, anti-regime forces can position themselves independently within the state (a proposition frustratingly corroborated by Vallejo and Jackson’s electoral successes). Sepulveda and leadership of the new Frente de Estudiantes Libertarios (FEL, or Libertarian Students Front. Editors note: in Latin America Libertarios are anarchists not Libertarians in the U.S. sense), in contrast, look to orient extant student forces toward galvanizing a non-CUT working class pole eschewing all contention for spaces within the dictatorship-bequeathed state.24 Their insistence that the broadly influential campus rebellions must branch out “transversally” is equally well-taken.

The regime’s difficulties will no doubt facilitate a growing militant challenge, but radicals’ ability to exploit the opportunity remains unclear. After deploying both traditional and innovative organizational resources and devising methods linking secondary and university grievances, the student movement is at a crossroads. After taking advantage of deepening elite divisions and developing strategies to agitate and pull public opinion behind a broad anti-neoliberal program, key decisions await. Activists built the movement in accordance with rising demands and real conditions on the ground, avoiding getting bogged down in cart-before-the-horse debates around regroupment or formal party blueprints. These qualitative advances have raised a new set of challenges. Now that popular insurgency is back, deciding on the most efficacious strategies is crucial.

After so much heavy lifting, what is at stake can be measured in historic terms. IA has correctly identified “the great risk that elites will regroup and generate a new governability pact, threatening … to push back much of what we have gained.”25 But if the seemingly bridgeable gap within the independent left is not addressed, radicals may miss the best chance since 1973 to constrain elite power and assert a popular alternative to neoliberal democracy.

Footnotes

- "Estudiantes de ACES se toman comando de Michelle Bachelet," Terra, Nov. 17, 2013.

- " Presidenta anarquista de la FECH expresa apoyo a toma de comando bacheletista," TerraTV, Nov. 17, 2013.

- Rodrigo Durán and Nicolás Sepúlveda, "No alcanzan los quorums para las reformas de Bachelet: Nueva Mayoría obligada a negociar con la derecho," El Dínamo, Nov. 18, 2013.

- René Rojas, "Chile: Return of the Penguins," Against the Current, no. 157, March-April 2012.

- Diego Zúñiga, "Aysén: Después de la batalla," Que Pasa, Dec. 27, 2012.

- Alexei Barrionuevo, "Plan for Hydroelectric Dam in Patagonia Outrages Chileans," New York Times, June 16, 2011.

- " Chile, Cloc-Via Campesina expresses solidarity with Mapuche People," Via Campesina, Jan. 23, 2013. It is worth noting that persecution of activists and militarization of southern Mapuche territories first intensified under Concertación governments’ application of Pinochet-era anti-terrorism legislation. This approach has led to at least four activists murdered by center-left governments. For a report on the Concertación’s prosecution of the war on indigenous activists, see Human Rights Watch, Undue Process: Terrorism Trials, Military Courts, and the Mapuche in Southern Chile. The best source for ongoing coverage of incursions into communities is paismapuche.org/. For reports of the conflict’s escalation over the past year see here and here.

- René Rojas, "Of Movements and Mayors," Against the Current, no. 162, Jan.-Feb. 2013.

- A typical example was on display in coverage, with no irony intended, of two key Santiago races by one of Chile’s leading mainstream papers: “By just over two points, former RN minister Andrés Allamand beat out his list partner, former Santiago mayor, UDI’s Pablo Zalaquett, in the Westen Santiago contest. … In Nueva Mayoría, PPD senator Guido Girardi gained a 12 point advantage over former Maipú mayor, Christian Democrat Alberto Undurraga.”

- Hugo Guzmán R., "La otra guerra de la Derecha," El Ciudadano, Nov. 23, 2013.

- Educational reform requires four-sevenths of Congress for approval (69 deputies and 22 senators), while constitutional changes require an even higher two-thirds vote (80 deputies and 26 senators). Even if the entrenched Christian Democrat and Socialist oligarchs cooperated, a highly unlikely prospect, Nueva Mayoría’s platform would not prosper.

- Both Jackson and Vallejo obtained more votes than Bachelet in their districts.

- "Gabriel Boric: “La actual institucionalidad no es capaz de contener las demandas estudiantiles”," El Mostrador, Dec. 12, 2011. An excellent report from Centro de Investigación Periodísta described the unfolding of the deal between the PCCh and Concertación this way: “The massive 2011 marches … not only damned Piñera’s government. They also rocked the Concertación whose leaders and parliamentarians were unable to jump on the protest wagon since its governments were primarily responsible for the crisis. … The offer then made by the three PCCh legislators was like a glass of water in the desert. The proposal was to jointly explore, as a “broad opposition,” university reform. The PCCh was well positioned in public opinion thanks to the leadership of its student leaders, particularly Camila Vallejo, and it reached out to the Concertación to devolverle el habla [help it find its voice].”

- Perhaps the most glaring example of the orthogonal interests of NM’s business and popular constituents is embodied in the successful run by Iván Fuentes. Fuentes will be the Christian Democratic deputy representing Aysén, location of the 2012 rebellion that he helped lead. Yet as he tries to advance the region’s anti-corporate demands, he will run up against the multi-million dollar donations that energy giants Enesa and Colbún pumped into the Bachelet campaign to secure her approval of the massively unpopular HidroAysén mega-dam project.

- Reuters, Elecciones: Mercado local se muestra dividido por alcance de reformas que propone Bachelet," Nov. 15, 2011.

- JP Morgan graciously added, “We believe that the majority of these initiatives, particularly those most likely to be approved and implemented, are already known by the market and have been factored into current price valuations”!

- Chile, with one of the lowest corporate tax rates among OECD members, raises 7.5 percent of its gross domestic product through corporate and income taxes, compared with the 11.3 percent average for the OECD. Business, while acceding to raising the corporate tax rate, will take a more recalcitrant position against Bachelet’s proposal to gradually eliminate the Fondo de Utilidades Tributables (FUT), a sort of tax-exempt pool of “development” funds. It is estimated that companies currently hold US$270 billion in these funds, or the value of the whole of Chile’s economy!

- "Bachelet y apoyo de la CUT: “Es un respaldo al programa que representa a los trabajadores en Chile”," The Clinic, Dec. 2, 2013.

- As reported online by El Mostrador, changes to labor rules, which CUT had been actively pursuing, were subordinated from jump to tax reform negotiations. One NM source who participated in talks with business leaders explained that employers were willing “to accept any of Bachelet’s reforms, save labor reform.” They were “willing to give up money [i.e. higher taxes], but not power.” When the deal was settled, Andrés Santa Cruz, head of Chile’s peak employers association, declared with satisfaction that “as it stands, the labor issue does not make us nervous.”

- P. Cádiz and J.M.Wilson, "Reforma que posibilita cambio al binominal sufre traspié por ausencia de diputados de la Nueva Mayoría," La Tercera, Nov. 20, 2013.

- "Patricio Melero: “la Concertación está preocupada de que haya un mal resultado para la derecha, porque se quedarían sin contrapesos al interior del gobierno”, The Clinic, Oct. 6, 2013.

- The Communist Youth have interpreted NM’s constitutional reform pledge as a call for an “institutional refoundation” via a constituent assembly. Yet following in the footsteps of Venezuelan and Bolivian state refoundation, which could enable forms of political participation not dominated by partisan elites, and, more worrisome still, mandate state-guaranteed social rights which post-authoritarian orthodoxy has made the exclusive domain of the market, is clearly out of the question. While Vallejo and Jackson continue clamoring for a Constituent Assembly, Bachelet and her handlers talk only of achieving a “new” constitution through a restrictive parliamentary amendment process.

- Tomás Torres and Eduardo Cárcamo, "Reflexiones libertarias en torno al período en Chile," Anarkismo.net, Oct. 22, 2013.

- Ibid.

- "Este año, ¡a tomar en nuestras manos la educación que queremos!," Izquierda Autonoma, July 23, 2013.

Chile left politics Thanks for the excellent article on Chile. It’s hard to evaluate the strength of the left (or center left) in CHile. That’s partly because despite Chile being one of the most unequal societies (as the article says), there is virtually no extreme poverty — which is unique in Latin America. I believe that’s the result of “new deal” type policies from before Allende plus some UP programs which were so popular they were continued under Pinochet. In addition the center left pretty much gave up grassroots organizing after the Concertation came to power (they were more ONG than grassroots or labor based, and many got government jobs), while the right wing made inroads in the poblaciones largely through distributing food, presents, etc. In other words, the poor can’t be counted on to be solidly left or even center-left. Many voted for Pinera. Classes with “rising expectations” don’t always support the left, even if they have benefitted from redistributive programs. Voting stats (7% to the non-NM left) don’t mean much given the high abstention rates and those leftists who voted for NM as the lesser of two evils, eg the CP and many independents. I don’t know how many people marked ballots “CA’ for constituent assembly (to rewrite the constitution). There’s certainly at lot of mobilization, but from what I saw it was mainly youth/students/intellectual or focused on “social” issues like gay rights and abortion. There was student-labor solidarity during the strikes, and everyone seems in favor of some sort of education reform, but it’s hard to believe that militancy won’t die down if the NM makes some of the reforms mentioned in the article. Can the NM be forced to make more fundamental reforms? Get rid of the Pinochet-era harsh labor laws? Back off from privatization and neo-liberal policies? Get rid of the binomial election system? Are enough people desperate or seriously materially uncomfortable? When we were last in Chile (during the right wing govt) the most common complaint we heard was about “Transantiago” (the reformulated public transportation system), and most folks blamed the mess on Bachelet. I look forward to hearing more from Rene Rojas! Thanks.