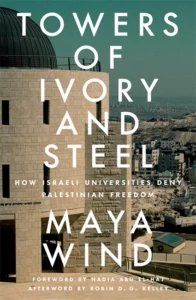

Review of Maya Wind, Towers of Ivory and Steel: How Israeli Universities Deny Palestinian Freedom. New York: Verso Books, 2024.

Review of Maya Wind, Towers of Ivory and Steel: How Israeli Universities Deny Palestinian Freedom. New York: Verso Books, 2024.

Maya Wind’s Towers of Ivory and Steel was published two months before the eruption of the U.S. University encampment movement against the Gaza genocide, but the book could serve as its manifesto. A scathing, meticulously researched study of the role Israeli universities have played in Israel’s colonization and occupation of Palestine, the book illuminates the direct relationship between ethnic cleansing and knowledge production, while explaining why Israel’s genocide in Palestine includes “scholasticide,” the destruction of Palestinian higher education that could conceivably help forge Palestinian resistance. The book is also a remarkable toolkit for the Boycott, Divestment, Sanctions movement, which since its inception has targeted the complicity of the Israeli university in the Occupation. Indeed, Wind’s is the most important book for the academic boycott movement since Omar Barghouti’s foundational 2011 book BDS: The Global Struggle for Palestinian Rights (Haymarket Books).

Wind starts with a history of what she calls throughout the “Settler University” in Israel. She begins with the important fact that three Universities were built by the Zionist movement before statehood in 1948, each of them “directly recruited to support the violent dispossession required for Zionist territorial expansion” (13). The Haganah, a Zionist militia, opened bases on all three of the new universities to “research and refine military capabilities.” (13) The Hebrew University, founded in 1918 at the apex of Mt. Scopus, was meant to signify Zionist political claim to Jerusalem. The Technion in Haifa and the Weizmann Institute in Rehovot sought to advance science and technology in the building of a new state—“Science,” said later Prime Minister David Ben-Gurion, “is one of the most powerful weapons for the realization of Zionism.” (56) To this day, the Technion remains a primary target on the BDS list for its construction of drones and weaponized bulldozers used to raze Palestinian homes. Many Universities across the world—including my former employer Purdue—have formal relationships with Technion.

Wind’s first chapter, “Expertise of Subjugation,” documents how a settler epistemology informs Israeli academic research and knowledge production. She shows how three fields of academic study—Archaeology, Legal Studies, and Middle East Studies—work in close relationship with the state and military apparatus to generate and legitimate Zionist domination of Palestinians. University-sponsored excavations of Palestinian land magically rename them as parts of Jewish history; legal scholars provide rationales for Israeli military’s bending and breaking of international law. Middle East Studies—the field Edward Said identified as the progenitor of “Orientalism”—in Israel functions to erase or stigmatize Arab or Palestinians and to discourage research or scholarship which challenges Zionist interpretations of the world. Even Arabic is considered a “foreign language” on some Israeli campuses, despite the fact that fully 20 percent of the Israeli population likely speaks it.

Wind’s chapter “Outpost Campus” details the role of Israeli universities since 1948 in what is officially known as “Judaization,” the state-sanctioned name for settler-colony ideology and practice. Critical to this is the role universities play in the spatial conquest of historic Palestine. For example, Hebrew University’s location on Mt. Scopus was critical to the “Judaization” of West Jerusalem. The University was built on the ruins of the Palestinian village of Sheikh Badr, whose residents were forced out of their homes by the Haganah military. After the Nakba, workers at the National Library and Hebrew University appropriated 30,000 books left behind by fleeing refugees on topics like Islamic Law. (The Nakba is in a way the original scene of Israeli scholasticide: by late April of this year, Israel’s war had claimed 195 heritage sites; 227 mosques and three churches had also been damaged or destroyed, including the Central Archives of Gaza, containing 150 years of history.) The University of Haifa’s construction in Galilee helped Judaize a region wherein Palestinian presence had been considered a “demographic problem.” The University’s Judaization included research and planning for the “mitspim” (or “lookout”) project meant to build over Palestinian lands and create new sites of surveillance for Jewish settlers. Perhaps the most well-known example of Judaization by Israeli universities is Ariel University built on stolen Palestinian land in the occupied West Bank. The University offers academic credits to students volunteering for night shifts as guards in twenty-eight illegal outposts across the West Bank.

This last fact amplifies Wind’s general thesis that in Israel the role of the University is so deeply embedded in military Zionism as to be almost indistinguishable from it. Her name for this is “The Scholarly Security State”:

Universities run tailored academic programs to train Israeli soldiers and security forces personnel to enhance their operations. University institutes and academic courses serve the state through research and policy recommendations, which are designed not only to maintain Israeli military rule but also to undermine the movement for Palestinians rights in the international arena. Departments and faculty collaborate with the Israeli military, government, and Israeli and international weapons corporations to research and develop technology for Israeli military use and international export. (93)

A key example of the “Scholarly Security State” is the Institute for National Security Studies at Tel Aviv University. After 195 protesters were shot dead during the 2018 non-violent “Great March of Return,” INSS organized a conference to consider how best to “spin” reports of the shootings as a public relations problem. INSS researchers also formulate policy for the state about how to combat the BDS movement, including recommendations for disrupting BDS organizing, and maligning BDS activists for connections with groups described as “terrorist.”

One of the most famous cases in Israeli academia provides a centerpiece of Wind’s next chapter. Historian Ilan Pappé famously left his position at the University of Haifa to teach at Exeter in the U.K. in part because one of his students, Theodore Katz, was attacked for research about the expulsion of Palestinians from the village of Tantura during the Nakba. Pappé is himself the author of The Ethnic Cleansing of Palestine, a groundbreaking account of how Jewish militias organized the massacres of thousands of Palestinians between 1946 and 1948. He has been a target of the Israeli state ever since. After the Second Intifada, Likud Party activists formed the group Im Tirtzu (“If you will it” in Hebrew) intended to “reinvigorate” Zionist ideology. Its tasks include monitoring Left-wing Israeli academics and intimidation of Palestinian students on campuses. In 2010, the Knesset Education Committee commissioned the group to create a report on “anti-Zionist bias” in Israeli academia. One result has been the continuous repression of any research by Palestinian or Mizrahi (North African) Jews which might challenge Zionist narratives about state formation or crucial events like The Nakba.

Wind’s final two chapters focus on how the Israeli University represses and discriminates against its Palestinian and Arab student populations. Less than 20 percent of Palestinian women and less than 10 percent of Palestinian men gather degrees from Israeli Universities. Palestinians constitute only 3.5 of faculty at Israeli Universities. Israeli Universities themselves are heavily guarded and gated—Palestinians students often compare the experience of attending University to passing through a checkpoint. Palestinian students routinely face racist taunts, arrests, or discipline if they engage in political protest on campus. As Wind summarizes, “From their entry into Israeli higher education, Palestinian students have been criminalized, police, and targeted by their universities in collusion with the state. Academic freedom in Israeli higher education does not apply to Palestinian students.” (168)

These conditions have only deepened and been exacerbated by events leading up to and including the current genocide. When the broad-based “Unity Intifada” broke out in 2021, Palestinian solidarity protests at Ben-Gurion University were violently suppressed both by the administration and Israeli settlers who surrounded students chanting “Death to the Arabs!” On-line campus forums were filled with death threats to Palestinian students, literally driving them off campus. Yet for many Palestinian students the overt repression of 2021 constituted a turning point. Said one graduate student organizer at Tel Aviv University, “The mask has come off. We learned that we ultimately can’t count on most of the Israeli academic institutions and students for support.” Said another, “We are a new generation of Palestinian students with a different understanding of our place at the university. We know we have to advocate for ourselves because no one else will protect us.” (192)

These words could well be spoken by students on U.S. campuses currently engaged in what has been called the “global student intifada.” Wind’s book uncannily shows us past as prologue: that the alignment of Zionist forces in the Israeli government and university foreshadow what Robin D.G. Kelly has called the current “unholy alliance” between support for Israel at the level of the U.S. state, pro-Zionist forces on campuses, and an American version of the “settler” legacy in the form of far-right white nationalist forces who have attacked the student encampments. These, events, too, have produced a “new generation” of students worldwide who have learned to “advocate for ourselves.” This conjuncture has generated the most significant threat to U.S. imperialism since the Vietnam war, and the most vigorous challenge to U.S. support for Israel as a Middle East watchdog for empire.

At the same time, Wind’s book should give a boost to students and BDS activists who have made both divestment from Israel, and a boycott of Israeli universities, primary targets. The book demonstrates how the U.S. settler University is a mirror up to Israeli higher education system right down to its own history of expropriation and theft of native lands. It shows how alliances between indigenous and racialized groups, anti-capitalist groups, and anti-Zionist movements are necessary for dismantling the settler University. The book also speaks to the immediate role of Israeli and U.S. universities in the current genocidal war: since October, Israeli universities have doubled down on their support for its student-citizen soldiers while U.S. universities have deployed state police and stood by at UCLA while right-wing white nationalists, Zionist forces and campus police cooperated in an assault on a student encampment.

These events underscore how crucial it is that the global student intifada become its own prologue: to protests against the Democratic National Convention in Chicago, for example, where Palestinian coalitions have already organized a march against Genocide Joe and to wider challenges to U.S. racism and imperialism fed by U.S. support for Israel. The movement of trade unions towards criticism of Israel—like the American Postal Workers union and United Electrical Workers union support for ceasefire—is also an important step for expanding the potential of the Boycott, Divestment, Sanctions movement into workplaces. Because of the encampment movement, there has more progress towards actual University divestment in the past two months than the past 10 years.

All these advances are necessary to dismantle the U.S.-Israel axis at its differential points of production. Maya Wind’s book has the potential to be a memorable and historic weapon in a war against Zionism that we now seem closer to winning.

Leave a Reply