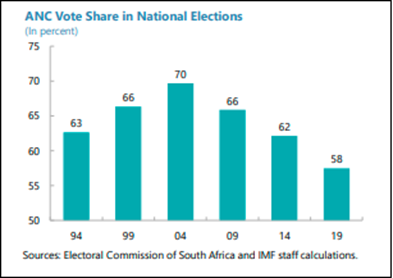

This article was written before the results of South Africa’s election were known. It now appears that the ANC’s share of the vote has declined to about 42 percent. The country is now facing a period of political turbulence as the political parties in parliament maneuver to form a coalition government. –NP editors

South Africa has a general election today [May 29] with 28m citizens registered to vote. Since the end of the apartheid regime three decades ago, the African National Congress (ANC) has won all the elections with substantial majorities. But this time there is the possibility that the ANC will poll less than 50% of those voting.

The loss of the ANC majority, if it happens, will not be due to any increase in the vote share of the main opposition party, the mainly white-led liberal Democratic Congress (DC), whose strength is concentrated in Cape province. The DC’s vote share is stuck at about 23%, more or less the same as in the last election in 2019.

The potential loss of votes by the ANC is to two supposedly more radical parties, split-offs from the ANC. First, there is the party of ex-President Jacob Zuma called uMkhonto we Sizwe (MK) that is polling about 10% and would take votes away from the ANC in the eastern Zulu heartlands. Zuma has been indicted for corruption and abuse of power when president.

The real worry for the ANC and behind them, South Africa’s business elite, is the rise of Julius Malema’s Economic Freedom Fighters (EFF). The EFF appeals to younger voters with its program to strip land from the wealthy, seize assets from the mining companies and spend the proceeds on education, free WiFi and electricity and 24-hour doctors’ clinics. Both the MK and the EFF are showing around 11% of the vote in the opinion polls.

Why is there the possibility that the ANC, the party of South Africa’s overwhelming black majority with the historic legacy of Nelson Mandela, will poll less than 50% of the vote for the first time? When I covered the 2019 election in a post, I wrote that “In those 25 years, the majority have not seen any startling improvement in their living standards, education, health and public services. Indeed, for many, particularly young blacks, things are even worse. Inequality of incomes, wealth and land is extreme; corruption in government and in the party of the black majority, the African National Congress (ANC), is rife.”

Now in 2024, the situation for most South Africans is even worse than in 2019. Since 2019, there has been the brutal experience of the COVID pandemic, the ensuing economic slump and a feeble recovery since. Economic growth has continued to slow almost to a stop. Indeed, real GDP per person is lower than in 2019 and even 2012.

The official unemployment rate is still well over 30% (8m people) and near 60% for job-seekers between 15 and 24 years old.

Manufacturing output is contracting and the deficit on international trade is widening. Government debt to GDP after the experience of COVID has reached a record near 70% of GDP.

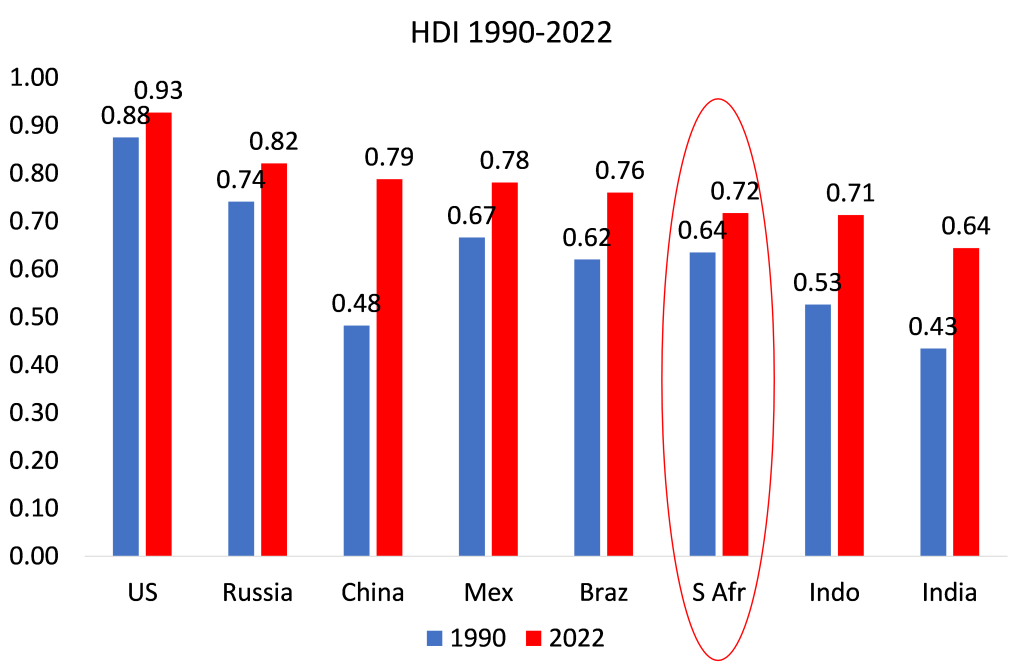

In general, life for the majority of South Africans has worsened since 2019. The World Bank has what it calls a Human Development Index (HDI) which measures key factors like life expectancy, health, education etc. South Africa’s HDI has dropped sharply since 2019.

Indeed, South Africa’s HDI level has been rapidly surpassed or equalled by its economic peers globally, like China, Brazil and even Indonesia.

Only the high level US HDI has grown more slowly than South Africa since 1990, when the apartheid regime was coming to an end.

| Growth | ||

| US | 5.9 | |

| Russia | 10.8 | |

| China | 63.5 | |

| Mex | 17.3 | |

| Braz | 22.6 | |

| S Afr | 12.9 | |

| Indo | 35.6 | |

| India | 48.4 |

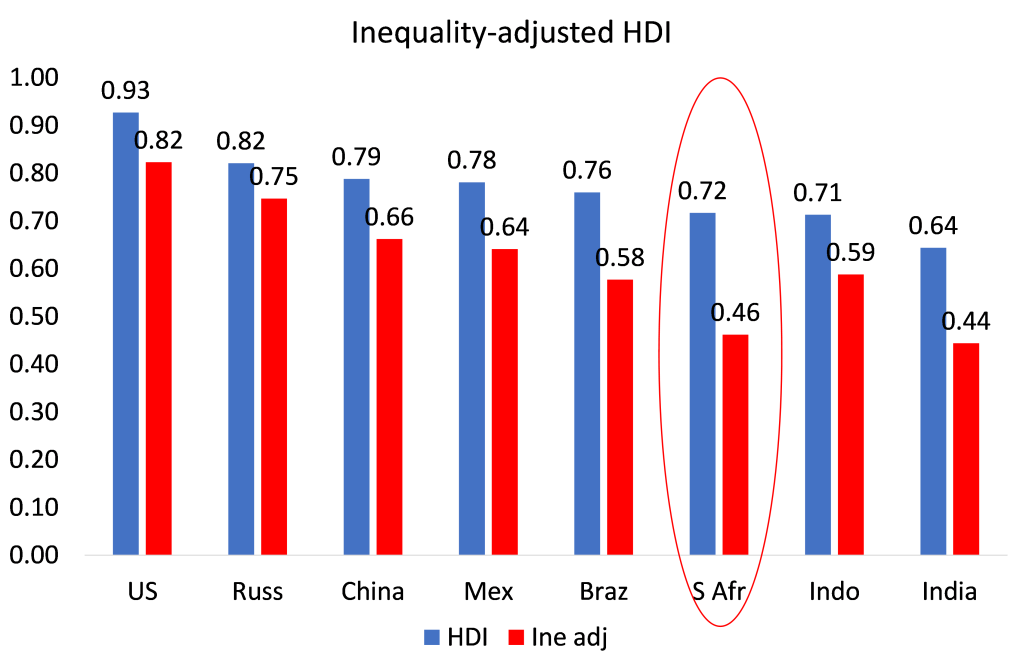

And then there is inequality and poverty. On World Bank levels, some 64% of citizens are living in poverty. Progress on extending access to basic services (such as water, electricity, and refuse collection) has stalled. Vulnerability to hunger has increased since the COVID-19 pandemic. An estimated 12.9 percent of the population was at risk of hunger in 2022, despite the expansion of social grants.

And South Africa remains the most unequal country in the world, having seen a widening gap between the haves and have-nots since the end of apartheid in 1994, according to the World Bank. The bank’s report, titled Inequality in Southern Africa: An Assessment of the Southern African Customs Union (Sacu), released this week, shows that the union is the world’s most unequal region with a consumption inequality over 40 percent higher than the averages for both sub-Saharan Africa and other upper-middle-income countries, the report found.

The World Bank report notes South Africa is characterised by “high wealth inequality and economic polarisation (particularly across labour markets)”. Wealth inequality is higher than income inequality, with estimates showing that the top 10% of the population hold 71% of its wealth, whereas the bottom 60% hold only 7%. This compares with 50% and 13% respectively for the OECD. No other country in the world can compete with South Africa’s inequality of income and wealth.

That inequality isn’t only seen in income and wealth distribution; it also manifests itself in unequal access to opportunities—education, health, and jobs—and regional disparities. When the HDI is adjusted for inequality of income and wealth, South Africa looks even worse. The World Bank’s HDI reduces South Africa to the level of India!

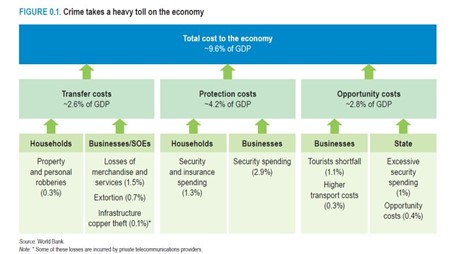

The bottom line is that South African capitalism presided over by the ANC has failed. It is decrepit and corrupt, generating power shortages and widespread crime. Crime is estimated to reduce annual GDP levels by 10%.

South African capital may have some large mining companies that make good profits, but the overall profitability of capital is low and falling. The big gains in profitability that arose after the end of apartheid have faded since the Great Recession of 2008 and ensuing Long Depression experienced globally. South African capital is heavily dependent on world economic growth and trade and is being strangled accordingly.

Source: Penn World Tables 10.01

South Africa’s business elite is desperately hoping that the ANC under President Ramaphosa will manage to survive with a majority in parliament that avoids any forced coalition with the radical EFF. The government is now claiming that it has resolved the electricity power outages, a perennial scourge for the daily lives of South Africans. Eskom, the state electricity provider, has now been able to keep the power on for 50 days. The government plans privatisation of power and transport on the grounds that this will ensure supply. After the election, the business elite will be pushing for more ‘business friendly’ measures on taxes, deregulation etc.

For its part, in an attempt to reduce voter support for the radical parties, the ANC has taken the plunge to win votes with a promise to introduce state health insurance for all citizens and a ‘basic income’ grant for the unemployed (but only within four years of winning the election). This would cost $17bn a year, which the ANC says will be funded by higher taxes, without specifying.

There is certainly room to raise taxes on the wealthy. An individual with a taxable income of ZAR100 000 used to pay tax at an effective rate of 33.8% in 1995; they paid tax at 19.8% in 2011 and 18% in 2022, on what the Alternative Information & Development Centre (AIDC) calls “the corporate income tax race to the bottom”. According to AIDC, a progressive net wealth tax of between 3% and 7% on the top 1% of the richest people in the country could raise more than R143 billion in revenue each year, which would cover most of the cost for a universal basic income grant.

However, the ANC seems reluctant to go down that road to fund any basic income, in case the wealthy and foreign investors desert the country. These measures will indeed worry the business elite and foreign investors. But then big business’ own proposed policies of privatization, tax cuts and deregulation are anathema to the electorate.

Indeed, the hopes of business for the improved health of South African capitalism are illusory. The South African economy cannot progress on a capitalist basis, with its massive inequalities, weak productive investment and trade deficits. The best forecasts for annual real GDP growth are for only 1.3% over the next parliament. That will never create enough jobs for unemployed youth (even if they get some ‘basic income’) and nothing is proposed to deal with the massive inequalities. The trade deficit is expected to widen. Public investment is projected to fall further while the government debt ratio will rise to near 80% of GDP.

Current President Cyril Ramaphosa is a former trade unionist who turned himself into a ‘businessman’ to make millions. He now presides over a corrupt administration in a weak and stagnant economy and a society with extreme poverty and inequality. South African capitalism is a basket case. How long can it hang on without a massive reaction from its people?

First published on Michael Roberts blog.

Leave a Reply