A defense of free speech on university campuses from unions across the country

During the COVID-19 pandemic, the largest teachers’ union local in the country consistently left members unsafe, confused, ill, and even dead.

[Editor’s note: An archived version of the event can be seen here: https://www.facebook.com/newpoliticsmag/videos/263390032588738/]

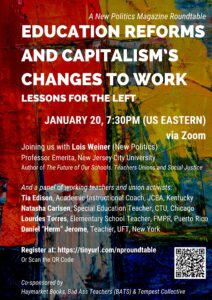

Join us January 20, 7:30pm (Eastern) to discuss what we need to learn and do to resist changes capitalism has made to labor and schools since Trump’s election . . .

Join us for a webinar Jan. 20, 2022, 7:30 pm (EST) as Lois Weiner and teacher union activists discuss how the revived attacks on teachers and their unions reflect capitalism’s chilling alteration of work. Details will be posted shortly.

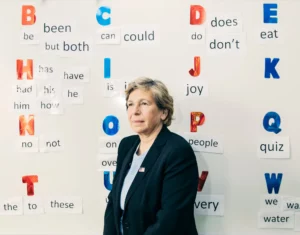

Randi Weingarten, President of the American Federation of Teachers, is once again doing the work of big money.

The rising movement among contingent faculty has pushed bills onto CA Gov. Newsom’s desk and into the budget reconciliation process in Congress.

This action dialogue on Monday, May 3 will focus on the many roles of unions during these increasingly complex times for educators, learners, families, and communities. Speakers include New Politics editorial board member Lois Weiner.

Teachers’ work is being transformed beneath our collective nose. We have missed an opportunity to combat the project in its earliest stages but we cannot delay in understanding and combating the new iteration of neoliberalism’s global project in education.

We shouldn’t assume that union and community efforts will inevitably succumb to corporate co-optation.

Bottom-up democracy through community schools sounds like a great idea, but there are many dangers from these ‘charter schools on steroids.”

Community schools are a way to address the challenges faced by low-income school districts; they also provide a unique opportunity to create bottom-up, democratically controlled school governance.

An analysis of debates among labor leftists about how a commitment to socialism “from below” should inform union activity.

We should let Miguel Cardona know we have his back if he defends what schools, teachers, students really need – while we simultaneously prepare for his not doing so.

Biden will endorse the old normal Obama handed to Trump, but he will also push profiteering and control of education through technology, a project supported by both Democrats and the GOP from the start of Trump’s administration.

Biden’s victory now requires confronting his advocacy of disastrous education policies during the Obama administration, enacted under Obama’s Secretary of Education, Arne Duncan.

School reopenings have become a point of political conflict on a national level, as parent, student, and teachers’ rights to have healthy, safe, equitable schools have been subordinated to the bipartisan consensus to put the economy and profit over human need.

The pandemic and the shutdown have taken a toll, but they now provide an opportunity to rebuild the American labor movement from the bottom up.

After over nine months of negotiations, on March 10, 2020 members of Saint Paul Federation of Educators (SPFE) took to the streets to fight for the schools our students deserve. Then, just one week later, we were back in our . . .

When I first considered writing a retort to Curtis Rumrill’s piece, “Why These Wildcats Will Weaken Us,” I thought it best to refute his argument on the grounds of its many inaccuracies. A retort . . .

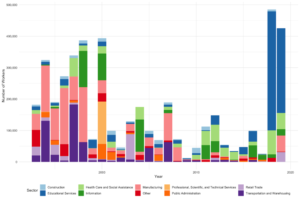

The 2012 Chicago teachers’ strike and the 2016 Verizon strike—the largest public sector and the largest private sector strikes in years, respectively—were warning shots.

After a short decline in strike activity in 2017, strike actions exploded in 2018 driven by West . . .