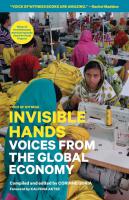

Corinne Goria, editor. Invisible Hands: Voices from the Global Economy. San Francisco: Voice of Witness, 2014. 388 pages. Map.

Corrine Goria, the San Diego-based lawyer and writers, together with a large team of other editors, researchers, transcribers, translators, and all the usual assistants who make possible the production of a book (and it is nice to see them all recognized on the verso of the title page) has produced an engaging and useful volume that is a kind of survey of work today in the capitalist world.

Invisible Hands: Voices from the Global Economy is a collection of interviews with sixteen workers and activists from eleven countries—the United States, Mexico, Guatemala, Nigeria, Zambia, Uzbekistan, India, Bangladesh, China, South Korea, and Papua New Guinea—who talk in the most straight-forward and down-to-earth way about their lives and work. The book is organized by industrial sectors—garment manufacture, agriculture, resource extraction (mining and petroleum), and electronics—though because some of those interviewed had other work experiences, we also learn about other industries and occupations.

When I received the review copy of this book from the publisher, I was planning a course on Global Labor that I am now teaching in the Urban Studies Department at Queens College. After looking the book over, I decided to adopt it for my class. Over the last three weeks the ethnically-diverse, evening class of mostly non-traditional students (from their late twenties to late forties) has read it and found it engaging, disturbing, and sometimes shocking. Workers tell us about their work for textile companies in Mexico or Bangladesh, for mining companies in Zambia or the United States, on plantations in India or North Carolina, or in the electronics factories owned by Foxconn or Samsung in China and Korea. To give a few examples:

· Ana Juárez a garment worker, and Martín Barrios, a labor organizer, tell their story of labor organizing experience in Puebla, Mexico.

· Neftali Cuello, a high school student and tobacco field worker in North Carolina describes her life and work amidst the toxic plants.

· Clive Porabou of the island of Bougainville in the autonomous region of Papua New Guinea discusses the struggle of the Bougainville Revolutionary Army against the Rio Tinto mining company.

· Li Wen, a former factory worker in China, tells us how he lost his hand in an industrial accident and what happened to him afterwards as he dealt with the company and the government.

The personal stories and the students’ reactions to them have provided an excellent basis for our class discussions and an easy way to introduce students to the world of work around the globe today. Since the book provides no theoretical framework and makes no attempt at analysis it allows the students to enter into an open ended discussion, one in which my students frequently compared their own life and work experience with that of the testimonials they were reading. With its stimulating interviews, short chapters, illustrations, large type and leading, and highly readable prose, it is not only an engaging book but an easy read. Anyone interested in work, especially industrial work in the developing world, would find this book a useful introduction.

Still, while generally happy with this book, both as a reader and as a college instructor, I think it has some weaknesses. Though some of the testimonials come from workers who were organizers or activists in struggle, many are from others who describe themselves principally as victims. While I too am moved by their truly sad stories of the deaths of coworkers, the beatings and firings, the injuries, often maiming, and illnesses, I felt that some of the stories became mawkish. I preferred the organizers’ and activists’ stories, but even they often did little more than mention the ideologies that motivated them, the strategies they employed, or the tactics they adopted. The interviewers might have pressed harder, asked more probing questions. And more of the stories might have discussed worker struggles—choosing, for example, a worker activist involved in one of the thousands of strikes taking place in China today.

The editors’ introductions to the workers’ stories are sparse, providing just enough information to be able to read the interviews for oneself—which from a pedagogical point of view is good. Nothing is forced on the reader. On the other hand, the editors fail to raise questions for the reader (or student) about what’s happening in the world of work. Some of these stories deal with the relationship between struggles for national self-determination and fights and for rights at work, as in the case of Bougainville in Papua New Guinea. Others show how the lack of political democracy and civil rights also has an impact on workers’ lives, as in Uzbekistan. Many of these personal narratives raise the question about the relationship between the multinational corporations and the national states in which they operate. We see in several chapters worker organized not only by labor unions but also by NGOs, the Catholic Church, a national liberation movement or a political party. Had the editors called these issues to the reader’s attention and perhaps asked some questions about those issues the book would have been even more effective. For example, are NGOs, usually staffed by middle class people and funded by foundations, really the best vehicle for worker organizing? Or perhaps such a leading question would undermine the book’s open-ended character.

If you conduct labor education for your union, work in the peace and social justice office of your church, or teach in a high school or college classroom—or if you’re just someone interested in reading a sweeping survey of work in the world today—this book is a good place to start. Though as the teacher you will have to ask many questions of your students that the editors have not raised. You and your students will need to read as well something about the history of the labor movement, about economics, about world politics, about the land-grab in developing countries, about the tremendous resistance movement in China today, and, no doubt, other issues as well. Of course Marx would be useful, essential. But with this book as your starting point you will have been plunged into the world of today’s working class: precariously employed, under-paid, working 10 or 12 hours a day six to seven days a week, but still dreaming of a better life, full of hope, speaking out for justice, and in many cases struggling for power in the workplace.

Leave a Reply