When I was a union rep, one of my most challenging assignments was assisting a Communications Workers of America (CWA) bargaining unit at a Boston-area telemarketing firm. Most CWA members in New England had call center jobs at the phone company, with good pensions, health insurance, and full-time salaries. As service reps, they fielded in-coming calls from customers with problems, questions, or new orders to place. In contrast, the telemarketing staff only interacted with the public, on behalf of various clients, via out-bound calling. Like the workers depicted in Boots Riley’s hilarious new film, Sorry to Bother You, they made cold calls to people who did not want to bothered, at dinner time or anytime, with a pitch for a new product, service, or donation to a political cause.

Even with a union contract, CWA’s telemarketing members in Somerville, Mass. were an unhappy lot—and for good reason. Their work was machined-paced by a “predictive dialer.” The quality of the lists they called, for fund-raising purposes, varied widely. Their base pay was low and earning more required navigating a byzantine bonus system. Benefit coverage was skimpy compared to the phone company. Yet, when we tried to negotiate improvements, a company whose clients included major environmental groups and Howard Dean’s presidential campaign hired Jackson, Lewis, a leading anti-union law firm to drag out bargaining for months and soak up money that could have been spent on its workers.

This particular call center was filled with “over-educated” part-timers, juggling other jobs or careers, because it did offer flexible hours. Nobody planned to stay long, however, because who wants to spend all day enduring rejection—hang-ups, name-calling, cursing, or long conversations with lonely people who end up giving or ordering nothing, because they are short on cash too.

Amid such shop-floor frustration and discontent, the telemarketing industry does produce stars–brilliant phone conversationalists who can charm almost anyone out of a few bucks for a magazine subscription, a charitable organization, political cause or candidate. Now 48 years old, Boots Riley was briefly one of those top performers when a mid-1990s downturn in his music career forced the founder of The Coup to seek employment in what is now a $24 billion industry. He had already done a stint, as a Teamster part-timer, loading packages for UPS in Oakland; this time, to pay the rent, he picked up a headset instead, at a call center in Berkeley. As Riley’s hometown alternative weekly, the East Bay Express revealed last week, he toiled under “a punk manager with an anarchy tattoo who enticed workers with cash bonuses to ‘make the grid,’ office parlance for raising money. “

A co-worker familiar with his rap albums recalls hearing Boots use “the same gravely, raspy voice, I knew from Genocide & Juice going, ‘Sorry to bother you, ma’am, but…’” Riley put his past experience as a door-to-door salesman to good use, carefully calibrating his pitch for each assigned fund-raising project. “It was me using my creativity for manipulative purposes,” he confessed to the EBE. “Like an artist who could make a cultural imprint instead figures out what font makes you buy cereal.”

Manic Energy

Fortunately, for millions of potential viewers of Sorry to Bother You, Riley has also found a way to turn his call center experience—shared by millions of other U.S. workers—into a rare Hollywood film dealing with race, class, and the tension between personal ambition and collective action in the workplace. The first-time director employs the manic energy of a Spike Lee movie, rather than the slow, last century pacing of Jon Sayles, to produce one of the best depictions of labor organizing since Matewan (or Norma Rae and Bread and Roses, for that matter).

The workers involved aren’t the usual blue-collar union suspects—i.e. mill workers, coal miners, or immigrant janitors. Instead, they’re Bay Area denizens of the “new economy,” multi-racial millennial office workers stuck on the lower rungs of a regional job market offering tantalizing riches (and even affordable housing) for some, but a far more precarious existence for many others.

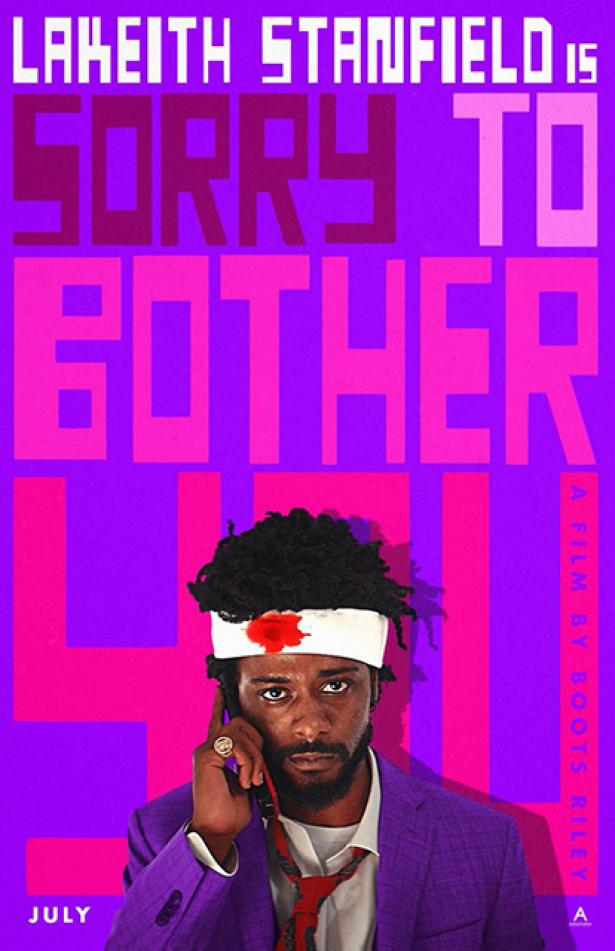

In Riley’s film, which opened nationwide last week, his fictional alter-ego is Cassius (“Cash”) Green, a struggling young native of Oakland played by Lakeith Stanfield. Cash is behind on his rent and living with his artist girlfriend Detroit (Tessa Thompson) in the converted garage of his uncle, whose home is facing foreclosure. “I just really, really need a job,” he desperately informs his soon-to-be-boss at Regal View, an Oakland telemarketer. Instructed, as all new hires are, to “stick to the script,” Cash stumbles through his first days of toil in a grim, crowded room full of partitioned workstations. Before being sent to their cubbyholes to dial for dollars each morning, Cash and his fellow “team members’ are subjected to a pep rally, led by managers who range from the moronic to demonic. (One urges them to employ their “social currency” to better “bag and tag” customers.)

Cash does poorly, with his phone contacts, until an older African-American colleague (Danny Glover) offers him some elder wisdom. “Hey, young blood. Let me give you a tip. Use your ‘white voice.’” Once any hint of Cash’s race or class background is scrubbed clean from his delivery, he starts making powerful connections with his telemarketing targets, zooming quite literally into their living rooms, dining rooms, bedrooms, and even bathrooms to make sales.

His reward, before long, is promotion to “power caller.” He becomes part of the Regal View elite, working many floors above the low-dollar calling room floor, in office splendor of the Silicon Valley corporate campus sort. Cash now wears a suit and tie to work, carries a brief case, and makes marketing calls to potential multi-million dollar clients of Worry Free. The latter is a global manpower agency led by Steve Lift, a tech industry titan with adoring fans and a new book entitled I’m On Top. Played by Arnie Hammer, the charismatic Lift is a cross between Steve Jobs and Hugh Hefner. Among Cash’s rewards for being a top “power caller” is the chance to party with Lift at his Playboy-style mansion; there he gets offered an even more lucrative but truly compromising position at Worry Free.

Revolt of the Precariat

Meanwhile, down in the lower depths of Regal View, a revolt of the precariat has been brewing—and before his personal ambition got the best of him Cash was part of it. Led by Squeeze, a young Asian-American caller (Steven Yeun), the “lowly regular telemarketers” are secretly planning to unionize. On an agreed upon day, all head sets are downed, fists get thrust into the air, and the telemarketers stage a 20-minute work stoppage, chanting “Fuck you, pay me” (no messaging confusion there).

As this labor-management dispute escalates into a full-blown strike replete with mass picketing and police brutality reminiscent of Occupy Oakland, Cash crosses the picket-line, only to become increasingly distraught by the choice he has made and ambivalent about its material rewards (a fancy car and swank new downtown Oakland loft!). “I’m doing something I’m really good at,” he tells one striker. “I’ll root for you from the sidelines.” But that’s not good enough for his feisty and creative girlfriend who threatens to leave him.

In the end, faced with the loss of Detroit and permanent estrangement from his own community and former co-workers, Cash becomes a fellow rebel against the worldview represented by Regal View and Worry Free. He blows the whistle on the latter’s sci-fi scheme to bio-engineer greater labor productivity and enslave workers, under the guise of providing them with “lifetime housing and jobs.”

The movie has a happier ending for the employees of Regal View than Riley’s real life co-workers experienced several years after the director left Stephen Dunn & Associates, the telemarketing firm that employed him in Berkeley more than two decades ago. In 1999, the East Bay Express reports, staff members there began a four-year struggle for union recognition, aided by Local 6 of the International Longshore and Warehouse Union (ILWU). Their long legal battle, against blatant union-busting, only ended when management moved the whole call center to Los Angeles.

In Sorry to Bother You, Steve Lift, the evil CEO of Worry Free, ends up reaping what he sowed. If only more workers struggles had a similar denouement, we’d all be better off. In the meantime, Boots Riley—Oakland activist, musician, and now film-maker extraordinaire—has made labor organizing in an almost entirely non-union industry seem doable and definitely worth the bother.

In 1976-77, Steve Early served as a volunteer for the Steelworkers Fight Back campaign, between better-paid tours of duty with union reformers in the United Mine Workers and Teamsters. He later spent three decades working as an organizer and International Union representative for the Communications Workers of America. He is the author of four books on labor and politics, most recently Refinery Town: Big Oil, Big Money, and the Remaking of an American City. He can be reached at Lsupport@aol.com.

Originally posted at the Stansbury Forum.

Leave a Reply