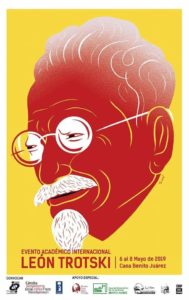

Trotsky Conference in Cuba Poster

Last week I was in Cuba to attend an academic conference on Trotsky. The night before the conference began I had arrived very late at the government-regulated air B&B where I was staying. First there had been a thunderstorm in Miami and lightening strikes, hail, and gusts of wind had prevented my plane from leaving on time and eventually it left two hours late. After I had passed through migration in Cuba I came into a room were a short young man was holding a poster with a portrait of Leon Trotsky. I walked up to him and introduced myself and he told me his name was Junior, welcomed me, and said that he had been waiting for me for hours.

He explained that a taxi would come soon to pick us up. The José Martí International Airport seemed to have few arriving flights and little automobile or pedestrian traffic at 11:00 at night. There were several taxis standing by, but Junior told me we were waiting for a specific taxi. He was a literature student and, though he did not know English, he was very interested in American poets and he asked me about Emily Dickinson, Walt Whitman, and especially about Ezra Pound. As a young man I too had loved poetry above all else and I had memorized and surprisingly still remembered Pound’s poem “Virginal” and recited it to him and then translated it into Spanish. I was astonished that I could still remember it and he was impressed that old American who had come to a conference about Trotsky and could also talk about poetry.

About a half-hour later the taxi arrived, one of those old cars from the 1940s and 1950s still used in Cuba, some of which have been beautifully maintained or restored, though this one was a jalopy. I got in and we started off, the car filling with exhaust fumes coming up through the floorboards. I was reminded of rolling wrecks that I had owned back in the 1960s and 70s when I was a college student in California. The Cuban car’s maximum velocity seemed to be about 35 miles an hour, a speed that could not be kept up because of the large potholes in the road. About an hour later, we arrived in Habana Vieja (Old Havana).

My young guide and the driver got us to the neighborhood in the historic center but we couldn’t drive in to the area because it had been made into a pedestrian mall, the streets blocked with old cast iron canons that had no doubt been taken from one of the forts that for centuries guarded the Havana harbor from pirates and from the English. So we stopped near Plaza Vieja and with them leading the way I dragged my suitcase along over the cobblestones until we arrived at the air B&B’s address on Mercaderes Street where I said thanks and goodbye to my greeter and driver. Clearly this was an old street from the capitalist era, probably from the early colonial era, since Mercaderes means merchants. There are in Cuba today still some merchants on Meraderes, but commerce is not flourishing.

Luckily at 1:30 in the morning a woman named Gracia was sitting by the gate to receive me—but also to inform me that my apartment, #13 was already occupied by two of my “compañeros,” presumably others attending the conference. Gracia told me she would call her husband who was better informed, but he had just gotten out of the shower, she said, which explains why it took him about 15 minutes to dress and come down. The four-story building had perhaps a dozen apartments, each of its apartments owned by a different person. “Well,” he said, “yes, that one is occupied. But the one next to it, #14 may be free, let me ask Patricia.” They called Patricia, who lived in another apartment in the building and eventually she got up, dressed and came down. “Yes,” she said, “I think it is free, but let me call Daniel who owns it.” She called Daniel who told her she could rent it to me and gave a price. So, finally, at 2:00 a.m., I was taken to a room, threw myself on the bed, and instantly fell asleep.

The next morning I arose and went in search of coffee and breakfast in that same neighborhood. The entire area is given over to tourism with many bars and restaurants that serve the thousands of tourists who come on cruise ships and tramp through Old Havana in search of something not found in Canada or Germany, but at 7:30 or 8:00 in the morning nothing seemed to be open on the main street. I turned into a side street where I saw what appeared to be a restaurant. There was no sign, just an open door six feet wide and eight feet tall and inside a counter, a broken chair, and a couple of boxes on which people were sitting. While I speak Spanish, I am not familiar with Cuban food and there was no menu, so I watched to see what the others were eating. I saw a man consuming what looked like a whole-wheat hamburger bun from which an omelet seemed to be spilling out. I asked him what that was called and he said, “tortilla.” “Tortilla” in Mexico is a corn pancake, in Spain it is a potato pie, but in Cuba it is scrambled eggs on a bun, or at least that is what a tortilla was in that restaurant.

I ordered a tortilla and given my hunger the whole-wheat bread and eggs tasted great. But, it turned out, there was no coffee. When I went to pay for the sandwich, all I had was a bill for 10 CUC, the currency principally used by tourists that is pegged to the dollar while the cost of my sandwich was just a few CUP, a few pennies, in the Cuban currency used by the local residents, The clerk said he had no CUC change and shrugged his shoulders. A woman in her sixties who sat on a chair half-in and half-outside the door, apparently the owner or manager, turned to me and said, “Don’t worry about it. You don’t have to pay.” Then she insisted that I also have a glass of mango juice. The breakfast was indicative of the generosity of the Cuban people, but also of the worthlessness of the currency.

While I sat there drinking my juice, two men were talking loudly about the scarcity of things. No pigs, no chickens, no eggs. Later I heard similar stories in other places in Havana, so it came as no shock when I returned to learn that the Cuban government had expanded rationing on the day that I left. Chicken, eggs, rice, beans, cooking oil, soap and other hygiene products will all now be rationed.

The next day I discovered that at the Hotel Ambos Mundos, the famous place where Earnest Hemingway had lived for ten years and written three novels, was just a block away. Thousands of tourists passed through it every month, led by guides with flags or signs, some of them going up to look at Hemingway’s typewriter, jacket, and shoes. At Ambos Mundos, I learned, one could get coffee and a very complete breakfast of eggs, little pancakes, cold cuts, and juice all for 10 CUC. Of course there they don’t let you leave without paying.

The customers’ discussion in the poor little restaurant of the lack of food in Cuba was only one sign of the difficult economic and social situation. Since I was last in Cuba about 15 years ago, there were more beggars on the streets in the tourist zones, still many hustlers, and perhaps more petty criminals. I watched a couple of the latter for 15 or 20 minutes as one would go up to a tourist and start a conversation about helping his sister and then the other man would appear to help work the scam. They repeated the scene three or four times while I watched, looking for their mark. Prostitutes too work the streets, day and night, approaching the male tourists and drawing them into conversation.

All of these are, of course, symptoms of the poverty, which is largely a result of U.S. policies such as the trade embargo and blockade as well as the Helms-Burton Act. Though, when I went to change some money in the bank, the teller volunteered that the economy was a disaster, “and it’s the government’s fault,” he offered. He didn’t go into it, but Cubans are well aware that Raúl Castro’s government has failed in its efforts to produce more food and consumer goods. And now Venezuela’s economic collapse means that Cuba can no longer get cheap petroleum and must buy it on the world market.

The situation may not yet be desperate, but it is pretty depressing. Near my air B&B on Plaza Vieja there was an elementary school where I saw children just like my own four-year-old granddaughter going to their pre-K program. Now they will have to tighten their little belts because of the cruel U.S. policies. Walking out of the core tourist area, one is saddened to see the poverty, the run-down housing, the people wearing old clothes, the empty shelves in the stores. Where there is poverty, there is competition for jobs and for income and, as everywhere, immigrants are blamed. A taxi driver tells me that things in Havana have gone to hell because of the “invasion” of people from the East, meaning the eastern provinces of Cuba.

I spent the next three days in the first-ever Cuban conference on Trotsky, an academic conference largely attended by Trotskyists who had come from all over the Americas and Europe to attend the event. The organizers and the attendees saw the conference as an historic occasion because since Fidel Castro had moved Cuba into the Soviet camp in the early 1960s, Trotskyists had been imprisoned and Trotsky’s ideas have been taboo. After the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991, the Cuban Communist leadership began to view the Soviet Union as a failed experiment with a flawed system and, while recognizing the support that Cuba had received from the USSR, the Cuban government distanced itself from the Soviet experiment. With Cuba no longer part of the Communist camp and the Soviet Union now looked upon as a failure, Trotsky became less important. And perhaps that is why the Trotsky conference could take place in May of 2019.

What did this event, where 40 professors and independent activist intellectuals presented papers on virtually every aspect of Trotsky’s thought mean for Cuba? Was it simply like most academic conferences, just an occasion for specialized discussion of an abstruse topic? Or was this event symptomatic of something taking place in Cuba? Some of us wondered if this event suggested that some space was opening for more critical Marxist theories? Might it somehow presage a more open Cuba with freedom to discuss a wide range of political theories? Was this conference the beginning of opening the window and letting in some fresh air? Would Cuba become more democratic, allowing its citizens to engage in freedom of speech, freedom of the press, and the right to assemble?

As it happens, at the same time the Trotsky conference was taking place there was a test of democratic rights in Cuba. The 12th annual “Conga against Homophobia and Transphobia,” Cuba’s gay pride parade sponsored by the government’s National Centre for Sex Education (Cenesex), was supposed to take place but was suddenly canceled. The Cuban government called off the Conga, arguing that it was not advisable at this time of “international and regional tensions,” a clear reference to severe U.S. measures taken recently against Venezuela and Cuba. The government appeared to fear that the parade would lead to protests by right-wing Evangelical Christians, a group that has become a conservative force in various Latin American countries and helped to bring authoritarian governments to power in places like Brazil. At the same time the government also made the argument that the parade could not be held at a time of economic crisis.

The Conga organizers, however, decided to go ahead and hold the event anyway, without government sponsorship or approval. The LGBT activists stated that walking down the street holding hands and carrying rainbow flags would have no impact on the economy. And they were not prepared to back down because of the Evangelical Christians. But holding their own march crossed a well-known line: no independent social or political activity in permitted in Cuba. Still they went ahead. Some 300 LGBT activists marched down the Paseo Prado, but when they reached the Malecón, the five-mile long sea wall that stretches from the center of Havana to the Vedado and is one of the principal tourist areas, the police blocked the parade, leading to clashes and arrests. So, while a group can meet to discuss Trotsky and even his criticism of the Communist bureaucracy in Russia in the 1930s and the lack of democratic rights in the Soviet Union, one cannot in Communist Cuba walk down the street and continue down the Malecón holding hands and waving rainbow banners without Communist approval.

Most of those attending the Trotsky conference were Trotskyists and most supporters of the Cuban Communist government, even if some are more critical supporters. Within the conference no Trotskyist dared to suggest that Trotsky’s analysis of Soviet Union as a “degenerated workers state” controlled by an oppressive and exploitive bureaucracy might be applied to Cuba. The argument is always made as it has been for more than sixty years that Cuba is under attack by U.S. imperialism, which it is, and that therefore one must not criticize the beleaguered revolution. Some of the Trotskyists theoretically believe that a genuinely democratic socialism might better defend the Cuban people than its current top-down leadership, but to raise that notion implies the building of an independent movement against the existing one-party Communist state as well as demands for democratic rights. It implies the right to organize independent labor unions and an opposition socialist party. The Trotskyists will generally not go there.

Perhaps a small movement for democratic rights is developing in Cuba, but it was less likely to be found in the Trotskyist conference than in the courageous LGBT marcher who organized independently to walk down the Havana streets holding hands.

LABOTZ: “The Conga organizers, however, decided to go ahead and hold the event anyway, without government sponsorship or approval.”

FACT: This 12th annual Conga was organized by CENESEX, and it was called off by CENESEX. All the other activities for the annual Days Against Homophobia and Transphobia went on, as scheduled.

Hers’s the statement from CENESEX:

https://walterlippmann.com/clarifications-on-the-2019-conga/

It seems you are more enthusiastic a few LGBT people being arrested than you are about Trotskyists being able to freely discuss the Old Man’s ideas in Cuba, where that occurs rather infrequently.

“Some of the Trotskyists theoretically believe that a genuinely democratic socialism might better defend the Cuban people than its current top-down leadership, but to raise that notion implies the building of an independent movement against the existing one-party Communist state as well as demands for democratic rights. It implies the right to organize independent labor unions and an opposition socialist party. The Trotskyists will generally not go there.”

Which Trotskyists would those be? All the groups I know, while recognizing the reality of the pressure that American imperialism exerts on the Cuban people, and knowing full well that either the Latin American revolution will produce another series of workers’ states thereby allowing the Cuban revolution to continue forward, or that a defeat of the mass movement in Latin America means rolling back or defeating the revolution from within, believe proletarian democracy will be the guaranteer of the gains the Cuban working people have made.