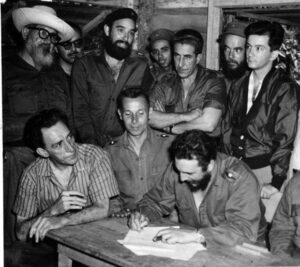

Fidel Castro signs the agrarian reform law. Also in the photo: Armando Hart, Minister of Education, Luis Orlando Rodríguez, and Antonio Nuñez Jiménez, the head of INRA (National Institute of Agrarian Reform) Photo by Cuban News Agency.

Most liberal and left academics and intellectuals tend to defend, or at least excuse, the Cuban government. This is to a certain degree understandable with respect to the defense of Cuba’s sovereignty and the opposition to the U.S. blockade, although it is possible and necessary to defend that sovereignty against imperialist intervention without defending or excusing the antidemocratic and highly authoritarian system prevailing in the island. After all, the right of nations to self-determination stipulates that they can and should decide their own destiny, but not as a reward to the good conduct of its rulers, but as a right against the actions and claims of foreign powers.

It is also understandable that many liberals and leftists outside of Cuba praise the accomplishments of the Cuban government in the areas of health and education. Nevertheless, these people generally ignore the great deterioration of these services, and of the general standard of living, since the collapse of the Soviet bloc, especially in the last few years. For example, according to a high functionary in the Ministry of Education, at the end of September 2023, Cuba had a shortage of 17,278 teachers (La Joven Cuba, October 30, 2023), and according to official Cuban statistics, between 2010 and 2022, 63 hospitals, 37 family medical offices, 187 homes for new mothers and 45 dental clinics had closed (El Toque, January 24, 2024). At the end of 2023, the Cuban government for the first time requested help from the U.N.’s World Food Program to remedy the substantial shortage of subsidized milk that children under 7 years old usually received. It is true that a significant part of the blame of the economic problems of Cuba can be attributed to the U.S. economic blockade, but the highly authoritarian and bureaucratic Cuban system is in this sense determinant because of its systematic impact on the economy creating apathy, indifference and inefficiency among both workers and administrators.

In addition, many important economic decisions have been arbitrary. For several years, the Cuban government has directed most of its investments to the construction of new hotels and other tourist facilities while dedicating a small proportion to the improvement of other economic sectors, such as agriculture and cattle raising. While food has been scarce, the investment in agriculture and cattle raising has remained at a very low level receiving 17.7 times less investment than tourism although hotel capacity reached only about 50 percent in the best years from 2016 to 2020 and has been much lower since then. The government has adopted this absurd investment policy to benefit GAESA, the great business chain of the Armed Forces, which owns, often in association with foreign capital, a large number of hotels and tourist enterprises. The fact is that the ruling economic system allows for such counterproductive and irrational decisions because there is no transparency or democratic control of the economy, neither by those who work in it nor by society in general. This relates to what is in fact the main issue regarding Cuba: the total absence of democracy, a system where for 65 years, the use of power has always been from above without any democratic control from below.

From Below or From Above?

The most surprising claim of some sympathizers of the Cuban system is that it is democratic. This is argued in spite of the dictatorial one-party state and the repression that State Security carries out on a routine basis to maintain the regime in power, and that many of its most important decisions, such as the agrarian reform in 1959 were mainly carried out from above and not from below. The Cuban Revolution has differentiated itself from other revolutionary processes in Latin America – especially in Mexico and Bolivia – and in other parts of the world – such as the Russian revolutions in1905 and 1917–, by the great control carried out through the decisive intervention of the Rebel Army to insure state domination.

There is no doubt about the great popularity of the Cuban government especially during the first years of the revolutionary process, the political radicalization of large sections of the Cuban people, and the popular desires for change to bring about an improvement in the standard of living. Nor can there be a doubt that Fidel Castro and the revolutionary government always maintained the political initiative and control of the revolutionary process.

Historically, the modus operandi of Fidel Castro was to convoke large demonstrations, especially in crisis situations, to announce new changes and laws so the people attending the demonstrations could raise their hands in approval of Castro’s proposals. This was done without any discussion, be it in the public square or in the media totally controlled by the government. The fact that these generally radical government measures could have been popular did not change the facts of a process that typically functioned from above when the government adopted important decisions.

Who Controlled the Agrarian Reform?

Undoubtedly, the most important decision in the initial stage of the revolution was the agrarian reform decreed in May of 1959. In October of 1958, Fidel Castro – who since 1956 had considerably moderated the radical platform of the 1953 History Will Absolve Me for the sake of broadening the social base of his movement and legitimate it – decreed a very moderate agrarian reform law in the Sierra Maestra. This was Law number 3 of October 10, 1958, which established the right to the land of the peasants who were not proprietors and held small parcels, but without establishing where these lands would come from or take any action against the big landlords. However, after January 1, 1959, it was clear that the revolutionary victory had been much greater than the revolutionary leaders had expected, mainly because Batista’s army had collapsed. This opened the door to much more radical possibilities, and Fidel Castro, in light of the hegemony of the 26th of July Movement that he headed, considerably increased his political power.

Before the adoption of the agrarian reform law, few people in Cuba imagined the degree of its radicalism. Because of this, a great number and variety of groups and organizations tried to weigh in on its content with the hope of influencing public opinion and be considered by the revolutionary leaders. This included even the sugar mill owners and big sugar landlords who donated tractors and other agricultural equipment to the government in a broad public relations campaign. Meanwhile, the law was being prepared in secret by a group that regularly gathered in Che Guevara’s home. Aside from Guevara, and the occasional presence of Fidel Castro, the group was limited to leaders of the PSP (Partido Socialista Popular, the name adopted by the Cuban Communists in 1944), as well as the “unitarian” faction leaders of the 26 July Movement who favored an alliance with the Communists. The leaders of the group of revolutionary nationalists that did not sympathize with the Communists and included figures like David Salvador (General Secretary of the Cuban Confederation of Workers or CTC) and Carlos Franqui (editor of Revolucion, the 26th of July newspaper) were excluded from these discussions at Che Guevara’s home. So was the Minister of Agriculture, Humberto Sorí Marín, who had prepared the moderate agrarian reform law in 1958.

The new law established 30 caballerías (1 caballería = 194.2 acres) as the maximum extension of land that an individual could possess. The expropriated land would be distributed in parcels no larger than 2 caballerías, although the cooperatives to be established would have no such limits. This norm was radical in comparison with the 1958 reform and with the very extended prerevolutionary view that emphasized the expropriation and distribution, with adequate compensation, of the abundant unused land owned by the big landlords. This reform was also radical in comparison with other agrarian reforms carried out in Latin America.

Although radical, the reform was evidently not communist since it emphasized the redistribution of the land and only vaguely referred to the not yet existing cooperatives. However, it did not even remotely suggest, as occurred several years later, that state farms would become the predominant form of agricultural organization. Regarding the compensation to the former proprietors, the law stipulated that it would not be paid in cash but would take the form of twenty-year state bonds that would be based on the usually low value of the land that the landlords had declared for tax purposes. But the bonds were never distributed. The law also marked an inflection point in Cuba’s relations with the United States, that became more hostile with Washington’s demand that the compensation be immediately made in cash. The domestic opposition, that had already vigorously objected to the urban reform decreed in March of 1959, which in many cases reduced rents as much as 50 percent, also demanded immediate cash compensation for the lands nationalized by the government.

In respect to who had controlled the agrarian reform, it is important to point out that when the alliance of the Cuban Communists (P.S.P.) with the government of Fidel Castro was still uncertain at the beginning of the revolution, the Communists supported several land occupations by peasants. Fidel Castro denounced such actions in a televised interview on February 16, 1959, and his government immediately decreed a law that stipulated that any person who participated in a land occupation would lose all rights and benefits provided by the future land reform law. In the same interview, he declared that any provocation to distribute land that ignored the revolutionaries (i.e, the government) and the law being prepared would be criminal. The PSP cautiously retreated and a few days later supported Fidel Castro’s agrarian policies. This new law eliminated as a significant phenomenon land occupation, whether promoted by the PSP or by any other group. Land occupations were typical of the political and social revolutions of the twentieth century, and their virtual absence in Cuba underlined the characteristics of its revolutionary process, particularly regarding the control exercised by Fidel Castro and his government.

To implement the new law, the revolutionary government created the Instituto Nacional de Reforma Agraria (INRA) [National Institute of Agrarian Reform] that divided Cuba into twenty eight zones of agrarian development headed by an INRA delegate. Significantly, these delegates were almost always officers of the Rebel Army subject to the military discipline of that institution and to Fidel Castro’s government.

Some historians and social scientists, like the Catalonian Juan Martínez-Alier in his Haciendas, Plantations and Collective Farms, (London: Frank Cass, 1977) and much more recently the American Sarah Kozameh – “Agrarian Reform and the Radicalization of Revolutionary Cuba,” (Cuban Studies, 51, 2020, 28-46) who echoed Martinez-Alier’s thesis have tried to present the adoption and implementation of the agrarian reform in Cuba with a much more democratic and from below appearance.

To achieve their purposes, the scholars analyzed several hundred letters that Cuban peasants sent to INRA and to Antonio Nuñez Jiménez (its director from 1959 to 1962) that contained complaints, petitions and demands; suggesting in this manner that the letters had pressured the government and played an important role in the adoption and implementation of the reform. Without a doubt, during that period, INRA and the officers of the Rebel Army that functioned as their delegates of that organization confronted many types of problems, political as well as administrative. These included injustices, such as when the former proprietors tried to subvert the reform, possibly with the complicity of some INRA officers such as the Catholic leader Manuel Artime who later broke with the government and went into exile. INRA suffered the weaknesses of the administrative apparatus of that epoch such as lack of experience and inefficiency, that often produced administrative chaos. Therefore, it is not surprising that its policies were occasionally erratic and unjust.

It is in great part for these reasons that there is an unavoidable ambiguity respecting the content and tone of that correspondence. After all, it is not the same to request or complain to the authorities about some problem, and demand something, as Martínez Alier suggests when he writes about the “peasant demand” for “land or work.” Even in the case of correspondence that demanded something, one would have to see what force or threat backed up that demand. Here lies the great difference between this group of letters and very different phenomena such as land occupations, that have historically been an expression of the autonomous power of the peasantry that as we have seen did not characterize the Cuban revolution. In truth, the use of messages to the representatives of power through letters and other means to transmit complaints and requests has characterized the Cuban political system for decades. This was one of the functions and responsibilities of Celia Sánchez Manduley as the personal representative of Fidel Castro.

Juan Martínez Alier sometimes seems to implicitly utilize a theoretical model that is not pertinent to the Cuban revolution and can confuse those that are not familiar with the course it has followed. For example, Martínez Alier refers to the agrarian reform approved in May of 1959 as a moderate middle class reform law (133), and to the revolutionary government as a coalition of liberals and leftists (135). It is true that a significant number of liberals were ministers in the government in the early days of the revolution, but what Martínez Alier ignores is that their permanence in the government was subject to Fidel Castro’s approval. Practically all these liberal ministers resigned or were forced to resign from their government positions by the Maximum Leader, as occurred with President Manuel Urrutia in July of 1959, shortly after the approval of the agrarian reform law.

Fidel and Raúl Castro, as well as Ernesto “Che” Guevara and INRA’s director, Antonio Nuñez Jiménez, were not the “reformists” that needed to be pressured to act in a more radical manner. They were revolutionaries, at least from the point of view of capitalism, although not from the point of view of socialism and democracy associated with classical Marxism, that has historically advocated for the self-emancipation of the working class and the peasantry as their class allies. Unlike Latin American social-democrats, liberals and “populists,” leaders like Fidel, Raúl and Che Guevara were committed to a clearly antiimperialist and anti-capitalist politics, although this commitment was expressed privately, especially by Fidel Castro, before 1959.

What scholars like Martínez Alier and Kozameh ignore is the political context of the period during which the peasants sent their letters. It was precisely at that time that an overwhelming support of the revolutionary government developed among an ample majority of Cubans, including the peasantry. This political climate encouraged great expectations and hopes for change among most Cubans, based not only on promises but on the achievements of the revolutionary government, and on its firmly anti-interventionist attitude in the face of U.S. threats. That is why it is a great error to see those letters as expressions of mistrust, discontent, or “pressuring” the government, when they were rather reminders to the revolutionary leaders to resolve problems that many times might not have been anticipated by the agrarian reform law.

Fidel Castro and his close collaborators knew that they could not ignore popular expectations, but neither Martínez Alier nor Kozameh provide the least evidence that the policies and actions of Fidel Castro and other revolutionary leaders at the national level were in any way affected by the letters sent by the peasants. What we do know is that INRA and the Rebel Army frequently reacted to peasant complaints and conflicts by “intervening” (taking possession) and then maintaining control of the lands under dispute. We also must bear in mind that many of these letters communicated administrative rather than socially or politically conflicted complaints.

The social bases of Fidel Castro’s power

If the distribution of power was concentrated at the top, how can we explain Fidel Castro’s extraordinary power to make the great decisions in Cuba? It is true that he was an intelligent politician and had communicative talent and tactical ability. But these qualities could only have a significant effect in the context of Cuba’s socio-economic and political structures in the 1950s.

In the first place, we must consider the collapse of Batista’s armed forces that made possible its total substitution by the Rebel Army headed by the Maximum Leader. The old army was principally an often-corrupt organization without any guiding politics or ideology and without the motivation to confront the revolutionary forces. It is worth noting that when a group of career officers unsuccessfully tried to overthrow Batista’s government in 1956, the victorious officers who sided with Batista referred to those who had lost as “the pure” (los puros).

In the second place, it is worth looking at the way in which U.S. imperialism exercised its control over Cuba in the 1950s. Since the Platt Amendment – that legally authorized U.S. intervention in Cuba’s internal affairs – was repealed in 1934, its political interventions became more indirect and limited. It could no longer, as in the 1933 revolution, give direct orders and land troops or threaten to do so on the island. It is true that the U.S. government sent weapons and war materiel to Batista, and that it intrigued and conspired to prevent a revolutionary victory when the dictatorship was on the verge of being overthrown, but once these efforts failed, Washington had no other recourse but to recognize the revolutionary government in 1959, although years later it tried to overthrow it on many occasions. We must also bear in mind that Fidel Castro’s challenge to the United States was greatly facilitated by the USSR, with which he later became closely associated, that had reached its peak of world influence a couple of years earlier, with the Sputnik phenomenon in 1957, and during the early years of the Cuban revolution.

In the third place, we must underline the virtual collapse of the traditional political parties, conservatives as well as reformist, after Batista’s Coup D’état in 1952. In fact, many of the cadres and leaders of the 26th of July Movement were recruited from the youth section of the Orthodox Party, the most important reform political party at the time, that suffered many divisions in the wake of Batista’s Coup and lost almost all its importance shortly after. One could say that the collapse of these organizations, and especially of the Orthodox party, created a vacuum that was soon occupied by the 26th of July Movement. The weakness of the traditional political parties was related to the weakness of a bourgeoisie and middle class highly dependent on the state apparatus and employment. Although these classes had grown economically since World War II, they were politically weakened by the fatalism that “nothing can be done here without the approval of the Americans.”

It is clarifying to compare the situation in Cuba with that of Venezuela in the same period. In that country, the Marcos Pérez Jiménez dictatorship was overthrown in January of 1958, exactly a year before Batista was overthrown, but as different from the island, Venezuela had a stable system of traditional political parties that survived the dictatorship, such as the Social Chrisitan Copei, the URD (Unión Republicana Democrática) and especially the social democratic party Acción Democrática and its historic leader Rómulo Betancourt. In fact, on October 31, 1958, these parties signed the Puntofijo Pact to stabilize the Venezuelan political system in anticipation of the scheduled December elections. That pact, which excluded the Communists, ensured the participation of the three parties in the cabinet of the winning party. Without a doubt, this difference between Cuba and Venezuela was a critical factor in preventing the collapse of the social and political status quo of the latter country for several decades.

Finally, we must admit that Fidel Castro had a lot of luck. Luck in surviving the Moncada attack in 1953 and the Granma expedition in 1956, when the majority of its 82 crew members died during the landing. Luck for having survived numerous assassination attempts and terrorist acts organized by the CIA. And he also had luck because potential leadership rivals such as Frank País and José Antonio Echevarría died in action in 1957.

The 1933 Revolution as a Contrast

Fidel Castro confronted a constellation of favorable structural factors for the development of a radical revolution, but that was not the case for the revolution that overthrew Gerardo Machado’s dictatorship in August of1933. It is perhaps ironic that the direct participation in the revolutionary process of the thirties was a lot greater than in 1959, when a good part of the support and sympathy for the revolutionaries, if certainly massive, was not directly participatory in the political struggle and decision making. Thus, for example, while the August general strike of 1933 was a direct and immediate cause of Machado’s overthrow, the strike declared on January 1, 1959, took place after Batista had fled the country. The purpose of that strike was to avoid a coup d’etat to prevent the victory of the 26th of July Movement. As that possibility disappeared within hours of Batista’s flight, the supposed strike, once it lacked an opponent, converted itself into a great national holiday accompanied by Fidel Castro and the Rebel Army’s triumphant march from east to west, until their arrival in Havana on January 8.

Although there were several working-class strikes with a political character during the Batista dictatorship – such as the 1955 strike by sugar workers – these were generally episodic and lacked the necessary connection and continuity to produce a cumulative and impactful political effect. The political weakness of the Cuban working class is understandable because it suffered a double dictatorship: on one hand, that of Batista at the national level, and, on the other hand, that of the union bureaucracy headed by Eusebio Mujal Barniol at their workplaces.

The strike called by the 26th of July Movement in April of 1958, that was presumed to be definitive in the struggle against the dictatorship, was a disaster that marked a step backward in the resistance against the dictatorship. In response to that failure, Fidel Castro called for a meeting on May 3, 1958, of eleven leaders of the 26th of July Movement in the Sierra Maestra in a place called Altos de Mompié. As a result of this meeting, full of disagreements and even violent pronouncements, Fidel Castro emerged with total control of the movement. The struggle in the cities, that would have been essential in any working-class struggle was subordinated to the guerrilla struggle led by a unified command under the orders of Fidel Castro in the Sierra Maestra.

It did not happen that way in the 1933 revolution. The working class, which was in its organizing stage during the hard Depression years, played a much more important role than in 1959. As the U.S. historian Gillian McGillivray tells us in her book Blazing Cane, Sugar Communities, Class, and State Formation in Cuba 1868-1959 (Durham, N.C.: Duke University Press, 2009) in August and September of 1933, of the approximately 100 sugar mills that were still functioning in the Depression era, workers occupied thirty-six mills and created “soviets” in an additional eight mills. All of this happened during a very militant strike by sugar workers, during which many of them travelled from one sugar mill to the next to extend the strike and consolidate it.

Nevertheless, the active struggle of workers, students and other social actors confronted obstacles that were absent in the fifties. Instead of the army disappearing under the impact of the advances of the opposing army – as would occur in the fifties – in 1933 a group of sergeants headed by Fulgencio Batista seized power and rapidly allied themselves with the United States in opposition to the revolutionary wing of the movement, led by Antonio Guiteras. These sergeants confronted the upper-class old Army officialdom and politically, and sometimes physically, eliminated them. They then proceeded to reorganize the army with the creation of a new officialdom composed of originally humble elements pliable to the political status quo.

With the Platt Amendment in force, the U.S. embassy, headed by Benjamin Summer Welles and later by Jefferson Caffery, was actively interventionist with the object of controlling within a conservative framework the direction of the revolution. Summer Welles, associated with Batista and other forces, was able to get Washington not to recognize Grau’s nationalist government (of which Guiteras was Minister of the Interior) that was then overthrown and substituted by several administrations manipulated by Batista, who rapidly promoted himself to colonel and later to general. Guiteras was assassinated by Batista’s soldiers on May 8, 1935.

While in 1959 Fidel Castro and his 26 of July Movement were overwhelmingly dominant in the opposition to Batista, the one that defeated Machado in August of 1933 was very divided. That included a schism on the left, since under Moscow’s orders the international communist movement had entered the extreme left and sectarian “Third Period” from 1928 to 1935, when the strategy and tactics of the “Popular Fronts” were inaugurated. In Germany, the results of this policy were tragic, because the Communists refused to enter a united front with the social democrats to fight Hitler. In the same manner, the Cuban Communists declined to support the nationalist and reform oriented government of the Hundred Days against Washington’s huge pressures. Nevertheless, despite its numerous frustrations, the 1933 revolution left a positive balance of social conquests and national affirmation that left the basis for the next political generation to try to complete the process initiated by the struggle against the Machado dictatorship.

The verticality of the 1959 revolutionary process took us by its own logic and dynamism to the extreme authoritarianism and total absence of democracy in today’s Cuba. This way of acting has become common sense at all levels of the official hierarchies. The most important task of a new Cuba will be to change from below through a radical change that manner of acting and thinking in the countryside, the factory, the office, and the school. That radical change will not come because of an authoritarian “solution” of the Sino-Vietnamese type nor of the goals and methods of what under Cuban conditions would be a Washington or Moscow sponsored capitalist authoritarianism.

[This article was originally published in Spanish in the Cuban critical journal CubaXCuba on April 8, 2024]

Leave a Reply