By: Jeffrey B. Perry

Columbia University Press, 2008, 624 pages

By: Jeffrey B. Perry

Columbia University Press, 2020, 988 pages

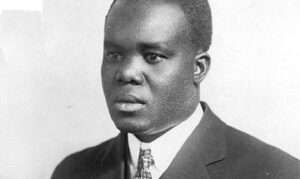

With the completion of his biography of Hubert Harrison, Jeffrey B. Perry has made a monumental contribution to our understanding of one of Black history’s most important yet neglected figures. Hubert Henry Harrison (1883-1927) was the first Black figure in the Socialist Party of America to organize a Black-led multiracial party formation, the Colored Socialist Club. Harrison spearheaded the World War I-era “New Negro” movement by founding the Liberty League of Negro-Americans and The Voice newspaper. He inspired Marcus Garvey to build one of the largest international movements of Black people in history. Harrison also pioneered the tradition of street corner speaking in Harlem, which seeded the intellectually eclectic, grassroots, and African-centered community culture that endures there to this day. As Perry argues, “Harrison is the key link in the ideological unity of the two great trends of the Black Liberation Movement—the labor and civil rights trend associated with Martin Luther King Jr. and the race and nationalist trend associated with Malcolm X” (Vol. 1, 5). Yet before Perry’s work, Harrison’s story was largely unknown. At last, we have a richly textured and two-volume scholarly biography that decisively restores to history a figure who made such important contributions to the Black radical tradition in the early twentieth century.

With the completion of his biography of Hubert Harrison, Jeffrey B. Perry has made a monumental contribution to our understanding of one of Black history’s most important yet neglected figures. Hubert Henry Harrison (1883-1927) was the first Black figure in the Socialist Party of America to organize a Black-led multiracial party formation, the Colored Socialist Club. Harrison spearheaded the World War I-era “New Negro” movement by founding the Liberty League of Negro-Americans and The Voice newspaper. He inspired Marcus Garvey to build one of the largest international movements of Black people in history. Harrison also pioneered the tradition of street corner speaking in Harlem, which seeded the intellectually eclectic, grassroots, and African-centered community culture that endures there to this day. As Perry argues, “Harrison is the key link in the ideological unity of the two great trends of the Black Liberation Movement—the labor and civil rights trend associated with Martin Luther King Jr. and the race and nationalist trend associated with Malcolm X” (Vol. 1, 5). Yet before Perry’s work, Harrison’s story was largely unknown. At last, we have a richly textured and two-volume scholarly biography that decisively restores to history a figure who made such important contributions to the Black radical tradition in the early twentieth century.

Perry’s first volume features intensive genealogical work on Harrison’s ancestry, deftly rendering the historical and economic backdrop for Harrison’s birth on the Caribbean island of St. Croix in 1883 and his upbringing in the Danish colony that the United States would acquire during World War I. Perry also sheds light on Harrison’s migration to New York City in 1900, his early experiences in debate clubs and study groups, and his break with religion and role in the anti-religious Freethought movement, along with the fateful termination of Harrison’s post office job by the “Tuskegee Machine” for his outspoken criticisms of Booker T. Washington.

The place where Perry’s first volume perhaps shines brightest is in his treatment of Harrison’s experience in the Socialist Party. Here we encounter the story of Harrison’s trailblazing theoretical writings on “the Negro and Socialism,” as well as his groundbreaking practical work founding and leading the Colored Socialist Club in Harlem. Failing to convince the party of the need for explicit anti-racist politics and special attention to recruiting African Americans for socialism, Harrison’s radical positions on issues like IWW-style industrial unionism, direct action, and the Paterson Silk Strike eventually drew the ire of the white and politically moderate party leaders. They responded to Harrison’s radicalism and racial arguments with, in his words, a “most contemptible form of persecution” (Vol. 1, 212).

As a socialist, Harrison had argued that due to the history of slavery, African Americans formed a group that was more essentially proletarian than any other American group. He maintained that the capitalist class sustained racism and racial prejudice in order to keep wages low, strikes infrequent, and workers divided. If not organized as socialists, Black workers would thus be used against the labor movement to the detriment of Black and white workers. Therefore, for Harrison “the Negro” formed “the crucial test of Socialism’s sincerity.” In its 1912 convention the national party took the position that racial differences were due to biology rather than socio-economic factors, and the New York local censured Harrison and aborted his precious Colored Socialist Club. Harrison’s experience led him to reconsider his faith in the capacity of the advocates of proletarian emancipation to manifest any substantive commitment to the most essentially proletarian group in the country. As Harlem-based historian John Henrik Clarke once quipped, Harrison “was a socialist until he discovered that most socialists are not true to the teachings of socialism.”

After parting ways with the white radicals in the Socialist Party, Harrison devoted himself to organizing and empowering the Black community in his home neighborhood of Harlem. In response to President Woodrow Wilson’s decision to take the United States into World War I in 1917, Harrison founded the Liberty League of Negro-Americans, which was the first wartime-era organization of the “New Negro” movement to emerge in Harlem. The League offered a Black radical alternative to the pro-war liberalism of the NAACP, and Harrison’s journalism exposed and thereby aborted W.E.B. Du Bois’ attempt to become an agent of U.S. military intelligence amid the patriotic fervor of World War I. Perry’s first volume ends with the Liberty Congress of Negro-Americans, the historic convening of dissident and “New Negro” activists in Washington DC in 1918 that elected Harrison its chairman and petitioned for federal anti-lynching legislation, despite the heightened wartime state repression of the Espionage and Sedition Acts. What a story!

Perry continues in the second volume where the first left off, chronicling Harrison’s travels to places like Virginia and Chicago, his work as a freelance educator, and the creation of his final organization effort in the form of the International Colored Unity League. Crucially, this volume also covers Harrison’s relationship to Marcus Garvey, his time as editor of Garvey’s Negro World newspaper, and his role as a left-wing voice within the Universal Negro Improvement Association. This is an area, among many others, where Perry’s work is illuminating, particularly for the way in which his reconstruction of Harrison’s life story and vantage point reveals new perspectives on the rise and fall of Marcus Garvey. Although Garvey’s movement drew much inspiration from the model of Harrison’s Liberty League, it ultimately came to embody an authoritarian form of Black nationalist capitalism and imperialism that repulsed Harrison and led to his departure from Marcus Garvey’s employ—not to mention some very trenchant criticisms of Garvey. Summing up Harrison’s significance to socialism and Garveyism, Perry writes memorably of how “in the period of the First World War, Harrison was the most class conscious of the race radicals, and the most race conscious of the class radicals” (Vol. 1, 17).

Although Perry is not the first person to write about Harrison or to try to preserve his legacy, the depth of this biography has surpassed all previous such efforts. Harrison contemporaries like J.A. Rogers and Richard B. Moore included Harrison in their writings about Black history and Harlem intellectual life. In the 1980s, historians like Wilfred Samuels and Portia James published the first academic journal articles on Harrison. Since then, other scholars have written a Harrison-inclusive article or book chapter here and there. Unfortunately, all of these works have been exceptions to the general rule of Harrison’s near-erasure from mainstream history and memory. For example, a recent book surveying 400 years of African American history by Harvard University professor Henry Louis Gates Jr. makes no mention of Hubert Harrison. Similarly, the University of Oxford’s five-volume Encyclopedia of African American History mentions his name only four times and only in passing. And there has been no book-length biography of Harrison … until Perry.

As a result, it has been a Herculean effort to recover Harrison, and the amount of labor Perry devoted to this objective is truly awe-inspiring. In the early 1980s, Perry wrote a PhD thesis on Harrison, in the course of which he built a relationship with Harrison’s descendants. They gave him access to a whole trove of Harrison’s papers, including his diaries, scrapbooks, correspondence, and various published and unpublished writings. In 2001, Perry edited and published A Hubert Harrison Reader. Then Perry compiled, sorted, organized, cataloged, and donated the papers to Columbia University, laying the basis for what is now the Hubert H. Harrison collection, much of which is accessible online. Drawing on this unique set of sources, Perry has rendered the chronology of Harrison’s life in stunning detail. Indeed, the biography achieves a standard of rigor and meticulousness that only his nearly forty years of research could produce.

One question inevitably arises in studying Harrison: Why has he been so marginalized in history and memory? As Perry explains, “Harrison was poor, Black, foreign-born, and from the Caribbean. Each of these groups has suffered from significant discrimination in the United States and limited inclusion in the historical record.” Not only that, but Harrison

opposed capitalism, white supremacy, and the Christian church—dominant forces of the most powerful society in the world. … Though he worked with many organizations and played important roles in several key ones, he had no long-term, sustaining, and identifying relationship with any [single] organization or institution, and so lacked the recognition and support that would have come with such a tie.” (Vol. 1, 13)

And finally, “Harrison’s willingness to directly challenge prominent leaders and organizations in left and African American circles stung many of the individuals … and groups … most likely to keep his memory alive” (Vol. 1, 14). That Harrison could remain so obscure for so long is also testament to how pervasive the very power structures that Harrison was contesting in the early twentieth century have remained, including their role in shaping how historiography is done.

Perry’s recounting of so many details of Harrison’s personal chronology sometimes leaves the reader wanting more emphasis on analysis that could draw out the deeper meaning of those details. For example, in Vol. 2 (613) we learn that in 1924, Harrison met an aging Ida B. Wells-Barnett in Chicago and was given a cordial reception at her home. Yet we get only one sentence about it. One wonders whether more could have been said about the significance of Wells-Barnett’s own groundbreaking role in spearheading the anti-lynching movement in which Harrison and so many others would come to labor. Similarly, one wonders what political or intellectual fruits came (or might have come) out of this historic crossing of paths between two titans of the Black radical tradition. Contextual perspectives like these could help form an even fuller appreciation of the significance of the details that Perry’s biography chronicles.

Nevertheless, Perry’s decisive and incontrovertible historical restoration of such a towering influence as Harrison invites both scholars and activists alike to rethink the meaning of the Black political and intellectual traditions upon which Harrison’s restoration has bearing. As a prime example, I myself began an exploration that is culminating in the writing of my own book on Harrison. Thanks to Perry’s work, I am able to use Harrison and his vantage point as a vehicle through which to rethink larger themes like Black Marxism, Black (inter)nationalism, Black Freethought and the church, African-centered knowledge in the diaspora, Black masculinity and sexuality, and the “Harlem Renaissance.” These are subjects whose discussions and reference points have too often neglected Harrison, despite his unique theoretical, practical, and at times contradictory contributions to them. Perry’s tribute is indispensable for understanding the great stimulus Harrison’s example contributes toward an expanded “sense of possibility” for Black liberation, both in Harrison’s time and in ours.

Leave a Reply