By: Llaves Dios

Slothco Books, 2018, $15

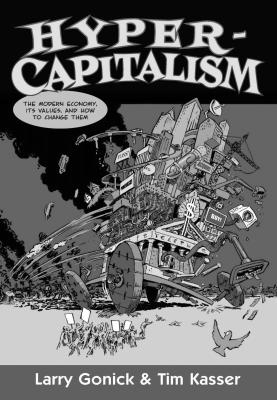

By: Larry Gonick AND Tim Kasser

New Press, 2018, $19.95

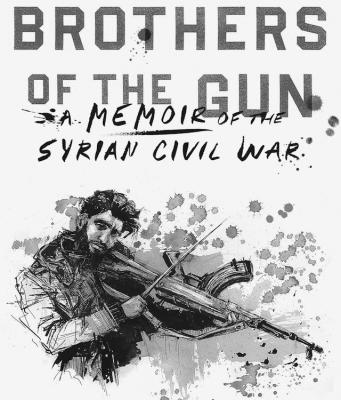

By: Marwan Hisham and Molly Crabapple

Random House, 2018, $28

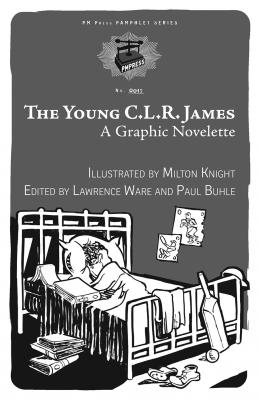

By: Milton Knight, Paul Buhle, and Lawrence Ware

PM Press, 2018, $6.95

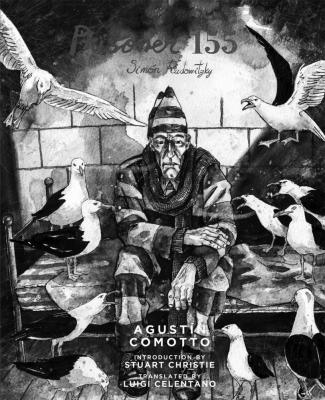

By: Agustín Comotto, Translation By Luigi Celentano

AK Press, 2018, $26

This season’s roundup of nonfiction comics includes self-published and small-press titles as well as noteworthy releases from major trade publishers. Topics covered range from consumer capitalism and imprisoned anarchists to Trinidadian social history and the war in Syria. Each of these titles deploys a distinctive approach to the challenge of folding political themes into visual narrative. In different ways, these books suggest that the forward march of political cartooning continues unabated.

Of the five books under review, the one likely to receive the most attention is Brothers of the Gun: A Memoir of the Syrian War. Its author was born and raised “in a poor neighborhood on the outskirts of Raqqa,” and he was the first member of his extended family to attend college. Along with his two closest friends, Marwan Hisham took an active part in the early protests against the Assad regime in 2011. “We want to shout our throats bloody,” he writes, “to force the sound of our voices into the most intimidating ears.” When the protesters are met with tear gas, the three friends went “from corner store to corner store, trying to persuade the scared shopkeepers to sell us cola, which activists in other cities say is the best antidote for tear gas.” “I hated that I had no voice,” Hisham explains. “I wanted to shout in the face of every corrupt motherfucker who thought he was better than me because his father was richer than mine and better connected.”

In those early days the protesters’ demands were simple: an end to corruption and authoritarian rule. But as Hisham reports, the nonviolent protesters and local resistance groups were outmaneuvered “by the Islamists whom Assad had released from Sednaya prison after the first months of protests.” Organizations like Jabhat al-Nusra and Ahrar al-Sham “did not believe in our revolution, or that there was a revolution, or that revolutions were anything more than an infidel innovation imported from the infidel West.” By early 2012 Raqqa was under the control of an uneasy coalition of religiously motivated militia groups. Between 2013 and 2017 it was an ISIS stronghold. Hisham navigated the incipient chaos by opening an internet café: “Fighters speaking different tongues from different countries and with skin of different colors, all were united in their thirst for infidels’ blood and our bandwidth.”

By the book’s end, his two best friends have perished and the Assad regime has retaken Raqqa, which along the way has been pulverized by bombing raids by multiple countries including the United States, as well as intense factional violence. With some reluctance, Hisham eventually retreats to Turkey, where he now works as a journalist. His voice is direct, humane, and self-reflective; the events he recounts are harrowing. The book’s power is amplified by Molly Crabapple’s inky drawings, which are interwoven into the text and which convey Raqqa’s slow-motion destruction. In recent years, Crabapple’s work has shifted from cartoony to pugnacious, with a nod to artists like George Grosz and Ralph Steadman. The combination of Hisham’s first-person reportage and Crabapple’s agitated linework is inspired.

A very different but equally inspirited collaboration is provided by Hypercapitalism, which fuses Larry Gonick’s witty narrative art and Tim Kasser’s social-psychological research on materialism and value formation. Gonick is an established cartoonist whose books include The Cartoon Guide to Genetics (1991) and The Cartoon Guide to Algebra (2015), while Kasser teaches psychology at Knox College. Their book explains how “global, market-worshipping hypercapitalism threatens not only human well-being and social justice, but also the planet itself.” Their approach is anti-consumerist, and broadly social democratic, and they insist that “private enterprise does great things.” They also maintain that “when the ‘product’ is a public service, the profit motive can run directly against the common good.” The strongest chapters are on “Corporations and Their Owners,” and “Capitalism and Values,” and the book ends with an impassioned defense of mass protest movements. Doctrinaire readers may object to some of their formulations, but as Bill McKibben notes on the back cover, “This book explains much about how the world works, and why it increasingly doesn’t.”

The Young C.L.R. James is a pamphlet-sized “graphic novelette” about the early development of one of the great Marxist authors of the twentieth century. It focuses on the tension between the conventional aspirations of James’s parents, who assumed he would follow in his father’s footsteps by becoming a teacher, and his early enthusiasm for cricket, Carnival, and jazz. Drawing heavily on James’s quasi-biographical Beyond a Boundary (1963), The Young C.L.R. James does a fine job of capturing the lost world of post-fin de siècle Trinidad, which at the time was a crown colony in the British Empire. The pamphlet includes an all-too-brief graphic essay on swing, one of James’s favorite musical genres. Milton Knight’s linework is exuberant, rowdy, and not a little comical, and seems suited to the task at hand.

Agustín Comotto is a gifted cartoonist and children’s book illustrator whose latest book tells the story of the Ukrainian-born Simón Radowitzky (1891-1956). Radowitzky was an anarchist of the “propaganda of the deed” variety who spent twenty-one years in a penal colony for using a homemade bomb to kill the Chief of the Argentine Federal Police, and his secretary, in 1909. Pardoned in 1930, Radowitzky marched off to Spain, where he fought alongside other anarchists during the Spanish Civil War. At the time of his death, he was working in a toy factory in Mexico. In his foreword, Stuart Christie describes Radowitzky as “a committed humanist imbued with a deep sense of justice who never expressed regret for the two lives he took.” While it may be an exaggeration to describe Prisoner 155 as “comparable to Art Spiegelman’s Maus and Marjane Satrapi’s Persepolis,” Comotto’s pages are engaging, and anyone with an interest in early twentieth-century anarchism will be intrigued.

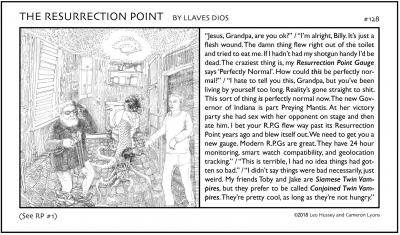

The Resurrection Point collects a year’s worth of online comic strips that combine horror tropes, weird fiction, and spooky imagery. “While we drift blissfully through our stupid boring lives,” write the authors—Llaves Dios is apparently a pen name—“our reality lies perched upon the edge of the Resurrection Point, the demarcation line for the safety zone of existence, with only a slight push needed to topple us over onto the other side.” Rather than celebrating historical struggles, or championing a post-capitalist project, the strips offer a skewed, nonlinear perspective on a dangerously near future. At first I was baffled by the authors’ obsessions with magical toys, time travel, and pancake syrup, but as I read on I became charmed by their commitment to the impossible task of forging something new. The other books under review are committed to things like reason, evidence, and literary realism. But in the era of Trump, surrealism may have its uses.

Leave a Reply