By: Edited and with a commentary by Art Spiegelman

New York: Abrams, 2016. Boxed set, 148 pp plus unnumbered art pages. $250.

Reading, actually looking obsessively at the pages of, this volume and non-volume inevitably brings to mind an unpublished, uncompleted 1967 essay by Herbert Marcuse, “Lyric Poetry After Auschwitz,” translated and published after his death. Here Marcuse says, in part,

What is involved is more than the “tragic experience” of the world of death and destruction, cruelty and injustice. . . . The Ultimate cannot be re-presented, cannot become “literature,” without mitigating the horror. This is the guilt of the aesthetic form which is essential to art: sublimation. And the Anti-form, the negation of form, remains literature while the slaughter continues.

Quite so. Artist Si Lewen, survivor of the Holocaust, brought to abstract modernism his notion of horrors, creating what might be called the human saga as war, and war as the human saga summed up. In the lucid explanation of his friend Art Spiegelman, the artist’s work is allied with and inspired by the “wordless novels” of Frans Masereel, the Belgian woodcut master so popular with European high-literary types during the 1920s and 1930s. Spiegelman’s ongoing documentation of comic art, increasingly important in his own artistic ventures, has recently highlighted Lynd Ward, an American version of the wordless novelist, actually a wood-cut artist of extraordinary talent. Ward, a great figure never much known outside of his children’s books, was raised to the canon of American art, in a three-volume set for the Library of America—the first graphic artist to reach that apex—through Spiegelman’s effort. The Lewen project follows a similar melody, albeit in a somewhat lower key.

From The Parade by Si Lewen, 1957.

Spiegelman suggests that in Lewen’s masterwork, beginning with children in a parade, images go to darker, darker, and still darker. The tonality becomes almost unbearable until we return, at the end, to the child in a mother’s arms. Mercy may triumph over horror yet. Masereel, Lewen told Spiegelman, had a decisive influence on the young artist, presumably in form but also doubtless in content. The great art of Masereel, and that of Lynd Ward as well, may be described as laconic, a commentary on the lamentable state of humanity, so obviously capable of happiness and community but denied both of these by the powers-that-be, perhaps also by a pitiless fate, a doom that seems to surround society and the individual even in the most optimistic moments.

Gradually, painfully, Spiegelman learned the elderly artist’s full story. Lewen barely escaped Germany at age 14, with an older brother, and after a time in Paris with a family friend, managed to get to the United States and live with his father, also a survivor. On an otherwise normal Manhattan day of the later 1930s, Lewen was in effect kidnapped in a park by a cop, taken out onto a lake in a boat, clubbed brutally and cursed as a Jew. He returned to shore so downhearted that not long after, he attempted suicide for a first time.

A few years later he was an Army volunteer in the struggle against fascism, seeing war up close and, interestingly enough, like my own late friend, noir filmmaker Abraham Polonsky, assigned to use his projected voice to encourage German soldiers to surrender. With his comrades, Lewen later entered Buchenwald. This was arguably the learning experience that set the aspiring young artist upon a life’s work. His drawings are unique in many ways, but perhaps can be said to present the mixture or fusion of what resembles both certain vernacular forms (comic strips) and a kind of expressionism, lacking in dialogue as expressionism would be, naturally. Perhaps this is the element that drew Spiegelman to the artist and his work, as much as the theme of the Holocaust handled in a unique manner. Spiegelman’s Maus, the epic (and Pulitzer Prize-winning) two-volume work arguably rendered comics acceptable as “Art,” so that Spiegelman might be seen here as returning the favor.

Ghost, 20” x 40”, c. 2013 (from the collection of Art Spiegelman).

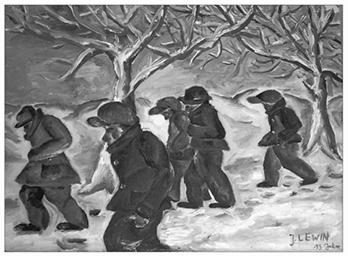

Workers in the Snow, watercolor, 1932.

A book of Lewen’s drawings actually appeared in 1957, from a small arts publisher, and made no particular dent. If Lewen had been raised briefly out of obscurity, he fell back into it again. Not that he lacked admirers, Albert Einstein among them. From a standard art-history standpoint, Lewen was one more abstractionist, of whom many, being Jewish immigrants, were trying to express at mid-century and after their sense of horror and their search for meaning “after Auschwitz” and so much else. This field was crowded with craftsmen better connected, if no more skilled or visionary, than Lewen.

Untitled, 36” x 60”, 1991.

Lewen’s work (he died in 2011) might never have emerged except that Spiegelman became fascinated with the work and with the artist, visiting him repeatedly. I am reminded of seeing an old print of a surrealistic painting—the horses of a Coney Island merry-go-round escape in the moonlight—in a Yiddish literary magazine in 1978, and seeking the artist himself, who was by that time living in distant Brighton Beach, Brooklyn, next to the boardwalk. There was Maurice Kish, surrounded by his paintings and as active, for a few more years, as his physical and mental conditions allowed. Lewen was luckier, in a way, because the “Odyssey series” seen here extended to nearly the end of the artist’s life. A project of more than three hundred pieces done 2002-2007, it manages to combine family snapshots, printouts from an unpublished memoir, postcards of travel, and details from seven decades of painting, some collaged and others Xeroxed. In the artist’s vision, this was prepared for an imagined, vast book, twenty by thirty inches, images somehow placed against each other. A megawork, in other words, of an exhibit virtually impossible to stage.

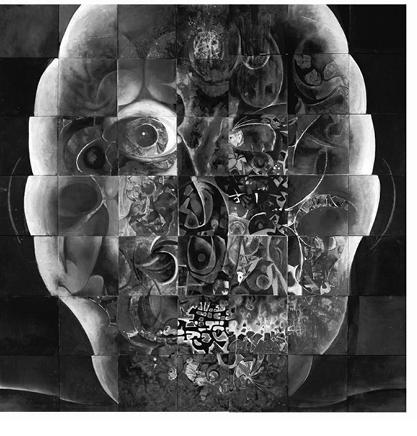

Ecce Homo (Behold the Man), a series of large works begun in January 2005 and continuing for about fi ve years. The large heads are composed of bits and fragments from previous works, some going back to when Lewen was fi ve years old. The examples here measure 200” x 200” overall and are made up of ten 20”-x-20” panels.

The “odyssey” of the volume’s title is also in part an odyssey of artistic form, as Lewen worked through assorted experiments, but more an odyssey of the artist’s own life.

At one point, frustrated with himself and the world, Lewen sought to cut off his hand with a power tool. He failed and … recovered artistically, the best as he could continue. Yiddish poet and painter Maurice Kish, who lost his hand-eye coordination in later years, began drawing pictures of his childhood shtetl in something resembling comic book art: his version of artistic survival. Lewen carried on experiments—some examples offered here—and thanks to sponsorship, achieved some real recognition through exhibits and such. It was a vindication that a widowed Lewen, bereft of his closest companion, must have relished. The accordion-like pages of Lewen’s later work are in fact a second book inside the first one. Spiegelman’s own text explains both, with a remarkable lucidity.

There is also something more here, artistically embedded in Spiegelman’s effort. For this point, we must leave Lewen and take up a Spiegelman favorite, nineteenth-century essayist Gotthold Lessing. How, the distinguished figure asked, were words and pictures actually related? Lessing’s influential argument had been that painting and poetry, each with its own proper sphere, have no valid relation, and that a mixture of forms inevitably ended in vulgarization. Masereel’s woodcuts (and Lynd Ward’s, later) found what Spiegelman calls a “loophole” in this rigid formula, with a single completed (and wordless) image followed by another and another. Are these avant-garde comics? Spiegelman does not give us a clear answer, but it must come down to the cheerful embrace of vulgarity.

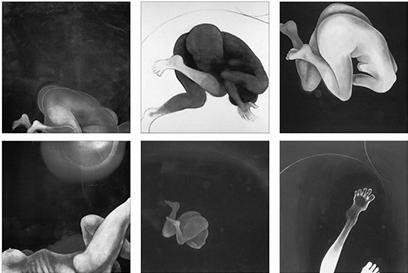

Excerpts from Eva, a series of 40”-x-40” acrylic panels meant to be presented interchangeably, in no specific order and with no preconceived right-side up.

Or does it, in an age when “comic art” is a functioning phrase (and museum description)? Can pictures, comic-art pictures, “talk to each other” when exhibited side by side, or proximate, in a public place? Is this the contemporary high-art version of the newspaper comic strip or the comic book? It’s a question that perhaps returns us to the Middle Ages when stories would naturally be told in pictures, stained glass windows in particular, before the Enlightenment intellectuals cursed this mix as suitable only to children and to adults with small minds. Can comics, even in museum exhibits, escape such a fate?

From The Parade by Si Lewen, 1957.

This is a question best left, perhaps, to future developments. Comics exhibits in substantial galleries of museums and other public places are now common in Europe, for instance. On this side of the ocean, they seem to come and go without making any deep impression on the critics or the public. If things change, Art Spiegelman will have had a notable role in the change. Should they change, would the change deprive comic art of its juvenile escape from high-art circles? For Spiegelman, the near exhaustion of the daily press and of the mainstream comic-book world has already decided the issue. I am not so sure.

All images: ©2016 International Institute for Restorative Practices

Leave a Reply