Reposted from our Winter 2017 issue.

Reposted from our Winter 2017 issue.

Marking an anniversary of a book’s publication is, appropriately, reserved for books that were widely read when they first appeared many years ago. Books we commemorate with an anniversary are ones that ushered in a new way of thinking and influenced the way society tries to make sense of the world. Martin Luther King Jr.’s last book, Where Do We Go from Here: Chaos or Community did neither of these things.1

Published in the long, hot summer of 1967, it was politely reviewed but dismissed. Milton R. Konvitz of the Saturday Review respectfully wrote that King had moved from slogans to programs “moderate, judicious, constructive,” and of “pragmatic tone.”2 Eliot Fremont-Smith of the New York Times wrote that King was “calling for a miracle.”3 Martin Duberman of Book Week suggested that King had a “tendency to substitute rhetoric for specificity.”4 The well-known progressive Andrew Kopkind, in the New York Review of Books, went so far as to state that “there is something disingenuous about his public voice and about this book,” while castigating the civil rights leader a few months before his untimely death as “outstripped by his times, overtaken by the events. … He is not likely to regain command. Both his philosophy and these techniques of leadership … are no longer valid.”5

Marginalized, called a sell-out, rendered irrelevant, an elder lost in the youthful spirit of the times, King faced one critic after another who, willing to admit it or not, harbored resentment toward the man who tried to confront W.E.B. DuBois’ classic dictum, “The problem of the twentieth century is the problem of the color-line.”6 One might think America, in the midst of an era of social tumult, would have welcomed this book’s analysis of what the project of a progressive social and civil rights movement should be. Instead, Where Do We Go from Here landed with a thud. King’s last and most radical book deserves better. With the benefit of history, we might consider how anniversaries can also mark a time when what was overlooked is revisited in order to provide us with a lens to view and understand the present.

King’s insistence that America reflect upon its recklessly imperialist and mindlessly materialist present was virtually erased from historical memory in the years following his assassination. In short order, the man was transformed into a cultural commodity (and a martyr) so that America’s self-congratulation on meaningful but limited progress on civil rights might hasten an end to the nation’s troubles at home. King’s death and subsequent canonization facilitated the fulfillment of a conscious need for white Americans to project an image of national redemption through little more than “greater understanding,” making up for the country’s history of slavery, institutional discrimination, and Jim Crow. America “mourned,” and that was it. Eager to move on, the American public largely dismissed King’s later work. Following his 1967 anti-war “Beyond Vietnam: A Time to Break the Silence” speech, parts of which were reprinted in Where Do We Go from Here, King was condemned by the media as a traitor and roundly criticized by African Americans and the general public more broadly.7 The year 1967 was the lowest point of King’s public life. By the end of 1968, following the death of King and Senator Robert Kennedy, Americans were quick to forget King’s message, impatient with the status of the civil rights movement, unsure how to put an end to the Vietnam War, and fatigued by the spirit of the times. In the 1968 presidential election, George Wallace received nearly ten million votes and Hubert Humphrey narrowly lost to Richard Nixon, who explicitly campaigned on a racialized law-and-order platform. Something significant had occurred that both altered the course of politics in America and moved King’s message to the dustbin of history.

The year 2017 will mark the fiftieth anniversary of the publication of Where Do We Go from Here. The book is perhaps the most radical statement of King’s analysis, criticism, and vision for change. Significantly, it links race and class as the twin pillars of the capitalist exploitation that is the generator of poverty, economic inequality, spiritual disenchantment, and racial animosity in America and across the world. As Cornel West correctly states, “The radical King was a democratic socialist who sided with poor and working people in the class struggle taking place in capitalist societies. This class struggle may be invisible or visible, manifest or latent. But it rages on in a fight over resources, power, and space.”8 King roots racial and class domination in the context of capitalist economic exploitation, explaining the persistence of black and white poverty and the political impotence caused by their mutual racial animosity. King advocated for an “alliance of liberal-labor-civil rights forces,” or a cross-racial class coalition, as necessary to implement a program meant to liberate Americans, both black and white, from poverty. Indeed, King wrote, “the Negroes’ problem cannot be solved unless the whole of American society takes a new turn toward greater economic justice.”9 King sees strength in class consciousness, a taboo topic in American public discourse and one that the early civil rights leader assiduously steered clear of. A revisit to the radical King is due; his analysis has been overlooked and has become relevant when one considers the political and economic realignments taking place in America in the last half-century.

This essay will argue that what makes Where Do We Go from Here so distinct lies in the fact that King’s analysis of global inequality, racism, and poverty is not abstract, moralizing, or merely discursive. King emerges in this text with an historical and materialist critique that links the raison d’etre of slavery, racism, and white supremacy to elite-class domination for the purposes of economic control and exploitation of the vast majority of humanity.10

The book is a rejection of the trajectory of America in the 1960s and a warning about the neoliberal shift taking place in a soon to be deindustrialized economy. Where Do We Go from Here is more poignant and urgent today than it was fifty years ago not only because the trends that King described have come to fruition, but because his “beloved community” provides a social philosophy and a political strategy for human liberation as well as a counterweight to the global ideological, economic, and political hegemony of neoliberalism. Whereas the United States and much of the rest of the world has doubled down on capitalism since the 1960s, King urges that we reject this evolution and instead redouble our efforts to create an alternative political, economic, and value system “beyond the traditional capitalism and communism.”11 By 1967 King, at last, embraced the revolutionary within.

This book is a reminder of how we might think about race, class, and poverty, forcing us to peer over the fence to see how the other half lives. Oftentimes, whites minimize or ignore the role of racism and discrimination in black poverty. Just as often, blacks minimize or ignore white poverty because whites are not the victims of racial discrimination. Both blacks and whites in the United States tend to minimize or ignore the role of capitalism and class exploitation. Each group often consciously (or not) embraces a kind of racial animosity as a false salve; not quite healing, but instead inoculating them against something much larger than they may be willing to accept. “In human relations,” writes King, “the truth is hard to come by because most groups are deceived about themselves. Rationalization and the incessant search for scapegoats are the psychological cataracts that blind us to our individual and collective sins.”12 In the “The Sword that Heals” essay, which appeared in an earlier book, King succinctly puts it, “The underprivileged southern whites saw the color that separated them from Negroes more clearly than they saw the circumstances that bound them together in mutual interest.”13

Where Do We Go from Here: Why Now?

Essentially, this book is not only about the experiences and struggles of blacks. King’s last book states that poverty in the United States and worldwide is not caused solely by racism and discrimination. There are millions of poor whites in the United States—more poor whites than there are poor blacks. To be sure, it is undeniable that the cause of poverty in the United States is in part rooted in racism and discrimination, but as King makes clear, it is also rooted in the capitalist economy and a divisive “I-centered” rather than a “thou-centered” value system. Capitalism is a system that is profit-centered and concerned with private property over the well-being of all people.14 Every American should read this book to understand, from possibly America’s greatest public intellectual and political/social theorist, that global poverty (as well as imperialism, environmental degradation, and civil war with its impact on human migration) is caused by racism, capitalism, and the policies of our own government. Just a cursory look at the world’s slums and favelas and the hundreds of millions of people who live in squalor, in danger from crime and disease, on the precipice of natural disaster—or perhaps at the millions of people who migrate from their native lands and risk their lives to escape the misery of war, poverty, and crime—will show the raw underbelly and material consequences of neoliberal global capitalism. King argues,

A true revolution in values will soon look uneasily on the glaring contrast of poverty and wealth. … It will look across the oceans and see individual capitalists of the West investing huge sums of money in Asia, Africa, and South America, only to take the profits out with no concern for the social betterment of the countries, and say, “This is not just.” It will look at our alliance with the landed gentry of Latin America and say, “This is not just.” The Western arrogance of feeling that it has everything to teach others and nothing to learn from them is not just.15

This should make us see, as King did, that a deeper analysis of domestic and global poverty needs to focus on both racial oppression and class exploitation worldwide.

Where Do We Go from Here: Beyond Civil Rights

In reading Where Do We Go from Here it becomes clear that King’s “beloved community” constitutes much more than the essential but limited gains of integration and civil and political rights. Realizing the futility of the narrow agenda set in motion by President Johnson as the Voting and Civil Rights acts were signed into law, King began pressing for more. For King, integration and equality meant a willingness on the part of Congress and the White House to fund economic advancements for African Americans, including affirmative action and government investment in education, housing, and employment programs targeting African American communities. King argues that justice requires affirmative action. “A society that has done something special against the Negro for hundreds of years,” writes King, “must now do something special for him, in order to equip him to compete on a just and equal basis.”16 According to King such affirmative, special treatment includes concrete programs such as “having a good job, a good education, a decent house, and a share of power.” King writes that the first phase of the civil rights movement had been about gaining equal political and legal rights, for which the 1964 Civil Rights and 1965 Voting Rights acts were important steps. However he explicitly states that the provision of these rights was merely a step in the struggle for equality, justice, and democracy rather the culmination. Furthermore, such advancements came at relatively little cost. “The practical cost of change for the nation up to this point has been cheap,” writes King.

The limited reforms have been obtained at bargain rates. There are no expenses, and no taxes are required, for Negroes to share lunch counters, libraries, parks, hotels, and other facilities with whites. Even more significant changes involved in voter registration required neither large monetary nor psychological sacrifice. The real cost lies ahead. … The discount education given Negroes will in the future have to be purchased at full price if quality education is to be realized. Jobs are harder and costlier to create than voting rolls. The eradication of slums housing millions is complex far beyond integrating buses and lunch counters.17

Affirmative action and targeted socio-economic programs are important elements of King’s program, but they are not comprehensive of his thought. The totality of King’s vision was greater than equalizing opportunities among racial groups. The King writings to re-read today consist of going beyond integration into the capitalist system. King’s goal was not the mere reduction of socio-economic disparities in wealth, income, employment, or poverty rates between whites and blacks. Such a goal would have equalized poverty rates for poor blacks and poor whites but would have left the fundamental systemic source of exploitation and poverty untouched. Recall the NAACP’s strategy to argue in the courts that segregated facilities be abolished in whole as inherently discriminatory, rather than to demand equality within a Plessy era of segregated facilities. Nothing short of full inclusion would be sufficient. Mitigating the extent of poverty would have cruelly accepted a society of millions of people devoid of freedom and dignity while still suffering in poverty. Instead, King’s notion of the “beloved community” was rooted in the abolition of all poverty, as its cause had both racial and class roots. King understood that the source of blacks’ poverty was not solely attributable to the system of segregation and racial discrimination. He believed that the only way to fully abolish black poverty was to make clear that it was bound up with the abolition of poverty for all groups. This, the late King came to see, was a project that required a challenge to capitalism and a “radical restructuring of the economy.” The struggle had entered a new stage. Questioning and challenging the status of the capitalist democracy called America was the new frontier in King’s nonviolent movement for equality in a nation built on principles he still deeply admired.

King called for a social and economic rights program not limited solely to African Americans. “Equality with whites,” writes King, “will not solve the problems with either whites or Negroes if it means equality in a world stricken by poverty and in a universe doomed to extinction by war.”18 Poor people of all colors and ethnicities have “common needs” for a war on poverty that “is no less desperate than the Negroes.”19 “This proposal,” writes King, “is not a ‘civil rights’ program, in the sense that the term is currently used. The program would benefit all the poor, including the two-thirds of them who are white.”20 King’s goal for the movement and the “beloved community” is guided by a commitment to economic justice that incorporates and transcends race. “The impact of automation, and other forces,” writes King, “have made the economic question fundamental for blacks and whites alike.”21 King knew, and implored others to recognize, that the issue was bigger than civil rights for blacks—rather he was making a case for economic rights for all as a validation of civil rights for all.

King argues that blacks have a “double disability.”22 Their condition is the result of racial discrimination and conditions resulting from an economic model that is rooted in economic exploitation and impoverishment. His critiques of automation, displacement, unemployment, and low wages are fundamentally critiques of capitalism.23 King understood that the drive for profits over people intensifies competition among the poor and working class for affordable housing, quality jobs, and decent education. White supremacy and institutional racism/discrimination ensure that these scarce resources are disproportionately distributed to whites. The distribution of these resources is little more than bread crumbs which, although they make life marginally better for poor whites (in their own eyes, most significantly) vis-a-vis poor blacks, are still inadequate to alter the same kind of material and political poverty experienced by black Americans. King understood that the racism of poor and working class whites is an ideological and economic strategy in the sense that the maintenance of racial discrimination limits competition for scarce resources, be it jobs or housing. As such it causes deep impoverishment among people of color, but it does not dramatically improve the material conditions of poor and working-class whites. Racism intensifies poor whites’ exploitation, using the material desperation of people of color for jobs and housing to enable employers and elected officials to keep wages at the poverty level and undermine collective action and labor solidarity. King well understood this fact, writing that the wage discrimination that blacks suffered in the South also “ironically not only deprives the Negro but its presence drives down the wages of the white worker.”24 This has been a recurring theme in American labor history where, in the face of demands by workers, employers have used tensions between ethnic and racial groups as tools to beat back demands for improvement in wages and working conditions, to break strikes, and to perpetuate the status quo rule of elites.25 Divide and conquer works in a system of acute poverty and insecurity.

Where Do We Go from Here: Beyond the ‘War on Poverty’

Where Do We Go from Here was published two years after the passage of the 1965 Voting Rights Act, the high point of the civil rights movement. In the two-year span 1965-1967 the United States experienced greater and more intensified social and political instability than previously. The war in Vietnam escalated to the point where a half-million U.S. troops were engaged in the conflict, with increased casualties on both sides. Lyndon Johnson’s War on Poverty was gradually undermined, politically and economically, by the increasing costs of the war. In northern cities, continued police brutality against people of color, and racial discrimination in employment and housing, resulted in diminished opportunities and quality of life, which led to riots in urban areas across the country, including in Newark, Detroit, Los Angeles, and New Haven. At the same time a structural shift in capitalism was underway. By the mid-1960s corporate investment was shifting not only domestically to the U.S. South but to low-wage foreign markets as well. U.S. firms increased their foreign direct investment as it became more profitable abroad.26 While it may not have been readily apparent at the time, American corporations adopted strategies that would result in stagnant wages and job insecurity. American corporations became more hostile to organized labor, demanding concessions in collective bargaining agreements, moving to non-unionized locations in the South or abroad, investing in labor-saving technology, displacing workers, and driving down wages. These shifts in capital and labor relations in the United States signaled a structural transformation in the postwar capitalist economy. Racial integration occurred at a time when the political economy was undergoing a movement away from industrial full employment, coexistence with organized labor, and a capitalist welfare state. The new environment would be post-industrial, unemployment-tolerant, non-unionized, and neoliberal, facilitating a weaker social contract and a relationship between capital and labor that placed racial animosities at the center of political and social life.27

The focus of King’s later work on anti-militarism and the Poor People’s Campaign make clear he was more than a civil rights leader: He was a passionate, articulate critic of capitalism. King perceptively saw the long-term implications of the economic shift that was emerging in the mid-1960s. Just as African Americans and other people of color won the right for access on a nondiscriminatory basis to employment, education, government services, and public places, the economy was changing, as machines were replacing the need for human labor and “good” paying jobs were harder to come by. These trends, already underway in the mid-1960s, were exacerbated over the next several decades, resulting in the contemporary situation of record corporate profits, stagnant wages, economic insecurity, underemployment, and stubbornly persistent levels of poverty.28

Where Do We Go from Here: A Revolution in Values

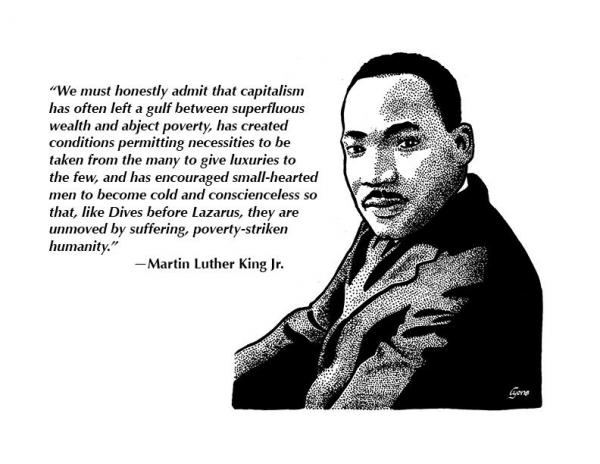

King implores us to rethink not only the workings of capitalism, but also the ideas that justify it. In particular, capitalist thought is rooted in the ideology of self-preservation and competition between individuals, groups, corporate entities, and nations. However, King has a different view on self-preservation. King suggests that “other preservation” is the first law of self-preservation: “It is the first law of life precisely because we cannot preserve self without being concerned about preserving other selves. The universe is so structured that things go awry if men are not diligent in their cultivation of the other-regarding dimension.”29 Following the ancient Greeks and modern socialist thinkers, King believed that humans are social beings. Humans need other humans to be free in order to fully develop their own individual and human potential. He writes, “‘I’ cannot reach fulfillment without ‘thou.’ The self cannot be self without other selves. Self-concern without other-concern is like a tributary that has no outward flow to the ocean. Stagnant, still, and stale, it lacks both life and freshness.”30 King’s educational background was vast and he was not one to shy away from praise for and reiteration of the thinkers of the Western Canon, including Aristotle, Augustine, Aquinas, Kant, Marx (subtly but masterfully), and here, Martin Buber. In Buber’s taxonomy, the I-it was distinct from the I-thou. The former relegates relations, and experience itself, into subject and object in a fixed state of engagement. The I-thou proposes a relationship that treats otherness as a thing in itself—an understanding that people are ends rather than means. King’s use of Buber’s I-thou is an important, although simple, plea for an authentic non-objectified understanding of others that would transcend the racism and capitalist exploitation of labor as the crudest forms of objectification of human beings. Forcefully, and with great clarity, King addresses this objectification, stating,

“We must honestly admit that capitalism has often left a gulf between superfluous wealth and abject poverty, has created conditions permitting necessities to be taken from the many to give luxuries to the few, and has encouraged small-hearted men to become cold and conscienceless so that, like Dives before Lazarus, they are unmoved by suffering, poverty-stricken humanity. The profit motive, when it is the sole basis of an economic system, encourages cutthroat competition and selfish ambition that inspire men to be more I-centered than thou-centered.”31

In King’s view, poverty in the twentieth century is not the result of scarcity of goods, but rather of a value system in need of radical change. Indeed, King writes,

“America is the richest and most powerful nation in the world. … There is nothing but a lack of social vision to prevent us from paying an adequate wage to every American citizen whether he be a hospital worker, laundry worker, maid, or day laborer. There is nothing except shortsightedness to prevent us from guaranteeing an annual minimum—and livable—income for every American family.”32

The source of poverty is in the economic and political distribution of goods. Scarcity in quality jobs, housing, and education are not for lack of resources. Instead, scarcity is the product of the conscious and willful decision on the part of the wealthy, corporations, and their political allies in government to create the conditions where exploitation and domination of people are easily attained. In King’s view it is very much a class project and an expression of power by economic elites to extract, exploit, dominate, and control the labor of the vast majority of the population and the resources of the world. King is explicit about the elite-class nature of historical and contemporary exploitation. He states that slavery is rooted in economic exploitation.33 He argues that the “birth of slavery is primarily economic, not racial.”34 Racism and white supremacy originated among elites using it to justify economic exploitation.35

The change King envisions to meet the “common needs” of the poor is a radical economic program. He calls for a true war on poverty and a “radical reordering of national priorities,” not merely a full funding of Lyndon Johnson’s War on Poverty.36 King’s program calls for either a policy of full employment or a guaranteed income tied to the median income (not some poverty-level minimum).37 King understands that these measures require a reassessment of capitalism and the profit-centered economy. “Now we realize,” he writes, “that dislocations in the market operation of our economy and the prevalence of discrimination thrust people into idleness and bind them in constant or frequent unemployment against their will. We also know that no matter how dynamically the economy develops and expands it does not eliminate poverty.”38 King’s economic analysis argues that capitalism’s drive to increase profits and reduce costs, including worker dislocations as a result of outsourcing or automation, creates poverty and economic crisis for lack of demand. King insists that the market has no inherent solution for this problem. “We have come to the point where we must make the nonproducer a consumer or we will find ourselves drowning in a sea of consumer goods.”39 King was no Luddite, averse to technological innovation, nor was he a protectionist or a xenophobe aiming to keep foreign products and people from the American market. King argued, “We must create full employment or we must create incomes. People must be made consumers by one method or the other.”40

King’s goal to abolish poverty through a program of redistribution in the form of guaranteed employment or a guaranteed income is not what makes Where Do We Go from Here radical. The radicalism of King consists in his insistence that there is a moral contradiction between the objective treatment of humans as means to exploit in a profit-driven capitalist economy and his belief that humans are ends in themselves rooted in the Christian and humanist traditions. King is critical of capitalism’s determination of a human being as a means to an end, whose labor exists to generate profit for another. “No worker,” writes King, “can maintain his morale or sustain his spirit if in the marketplace his capacities are declared to be worthless to society.”41 King challenges the capitalist valuation of labor as determined solely by what the capitalist market is willing to employ and at what price. Rethinking work, King says that once people have material means through a guaranteed job or income then society must be concerned “that the potential of the individual not be wasted.” “New forms of work that enhance the social good,” he writes, “will have to be devised for those for whom traditional jobs are not available.”42 Consistent with his revolution in values against racism, materialism, and imperialism, King argues for a society that conceives of work as an individually fulfilling and socially valuable endeavor. When he discusses the kinds of jobs that must be created, he states they must be those that raise the human spirit and maximize human potential. King approvingly cites nineteenth-century American progressive Henry George’s conception that work should exist for the improvement of humankind. “Work,” quoting George, should be that “which extends knowledge and increases power and enriches literature and elevates thought, … not the work of slaves, driven to their task either by the lash of the master or by animal necessities. It is the work of men who perform it for their own sake, and not that they may get more to eat or drink, or wear, or display.”43

Where Do We Go from Here: Tomorrow

Where Do We Go from Here links racism, discrimination, and poverty as a set of social, economic, and value-based decisions about the structure of modern society. King’s goals and programmatic vision are not limited to the borders of the United States. His project is a global one. “Racism,” he writes, “is no mere American phenomenon. Its vicious grasp knows no geographical boundaries. In fact, racism and its perennial ally—economic exploitation—provide the key to understanding most of the international complications of this generation.”44 The struggle for economic rights requires the building of a cross-racial, cross-cultural, class coalition that would construct a revolution in values away from racism, materialism, and militarism but also bring about deep structural changes to the worldwide economy. In 1967 King called for a radical reordering of national priorities and a clear departure from a class-based imperialist foreign policy. America, to address domestic and global poverty, could have responded to deindustrialization, automation, and the structural changes in global capitalism with the “Freedom Budget for All Americans,” which King endorsed.45 The United States and the West could have crafted and funded such a program to combat global poverty, similar to the efforts to rebuild Europe after World War II. Instead, elites decided that the surplus labor wrought by the neoliberal capitalist project called for widespread incarceration at home and a “planet of slums” abroad.46 King’s vision, neglected for over fifty years, can no longer be ignored, having reemerged in the contemporary political discourse thanks to political movements such as Occupy Wall Street, Black Lives Matter, and the Bernie Sanders “Revolution.” And because of the movement of political, economic, and climate refugees from Afghanistan, Iraq, Syria, Mali, Nigeria, Somalia, Honduras, Guatemala, Mexico, and Sri Lanka to nations of the developed world, we are confronted with conditions that will require a sober and critical look at the structure of the international order. King’s writings provide a way to understand the present and outline a path for the future.

In 2017, some may look back across the fifty years since the publication of Where Do We Go from Here and see a great deal of progress and hope for a brighter future in America. They will note that today blacks vote at higher rates than whites and that the nation elected and re-elected its first black president. Others will note the poverty, unemployment, and incarceration rates of African Americans. They will call attention to discrimination in the criminal justice system, voter registration, housing, and education as well as differentiation in life expectancy, infant mortality, and a host of public health issues. They will point to the names of unarmed black men and women killed by the police. Perhaps they note the opioid epidemic that is ravaging rural and urban communities. Other observers may point to the 17 million whites and 10 million Hispanics condemned to a life of poverty. As King made clear in his last book, these problems are not just problems of the black community or the inner city. They are not problems rooted and originating solely with race in America. Race is bound with class in America. America has produced a variant of capitalism that has impoverished populations of blacks, whites, and Hispanics; eroded upward social mobility; and pitted groups, whether racial, ethnic, or immigrant/citizen, against one another in a divide-and-conquer strategy that has enriched and empowered the wealthy to the detriment of the rest of the population. As we approach the commemoration of King’s assassination a half-century ago we ought to pause to revisit Where Do We Go from Here: Chaos or Community, King’s most radical text, as a prerequisite for our nation’s moment of reflection about King’s legacy. His book can help us to understand how we got here and where we might go from here. King’s humanism reminds us that “the bell of man’s inhumanity to man does not toll for any one man. It tolls for you, for me, for all of us.”47

Footnotes

1. Martin Luther King Jr., Where Do We Go from Here: Chaos or Community (Beacon Press, 2010 [1967]).

2. Milton R. Konvitz, “Power for the Poor,” Saturday Review (July 8, 1967).

3. Eliot Fremont-Smith, “Storm Warnings,” New York Times (July 12, 1967).

4. Martin Duberman, “Review: Where Do We Go from Here,” Book Week (July 9, 1967).

5. Andrew Kopkind, “Review: Where Do We Go from Here,” New York Review of Books (August 24, 1967).

6. W.E.B. DuBois, The Souls of Black Folk (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2008).

7. “The Story of King’s ‘Beyond Vietnam’ Speech,” NPR (March 30, 2010).

8. Cornel West, The Radical King (Beacon Press, 2015), xiii.

9. King, Where Do We Go from Here, 51.

10. King, Where Do We Go from Here, 76.

11. King, Where Do We Go from Here, 197.

12. King, Where Do We Go from Here, 71.

13. Martin Luther King Jr., Why We Can’t Wait (Signet Classics, 2000 [1963]), 36.

14. King, Where Do We Go from Here, 196-197.

15. King, Where Do We Go from Here, 198-199.

16. King, Where Do We Go from Here, 95.

17. King, Where Do We Go from Here, 5-6.

18. King, Where Do We Go from Here, 177.

19. King, Where Do We Go from Here, 53.

20. King, Where Do We Go from Here, 174.

21. King, Where Do We Go from Here, 51.

22. King, Where Do We Go from Here, 173.

23. King, Where Do We Go from Here, 170-175, 182, 196, 198-199.

24. King, Where Do We Go from Here, 8.

25. Robert L. Allen, Reluctant Reformers: Racism and Social Reform Movements in the United States (Garden City, NY: Anchor Books, 1975).

26. Intan Suwandi and John Bellamy Foster, “Multinational Corporations and the Globalization of Monopoly Capital: From the 1960s to the Present,” Monthly Review (July-August 2016), 114-131.

27. By the mid- to late 1960s union membership was already on its downward trajectory from its high point of 35 percent of the workforce in 1954. By 1965 the union membership rate was below 30 percent.

28. For instance, after adjusting for inflation the average hourly wage in 2014 had roughly the same purchasing power as it had in 1979, while most of the wage gains have gone to the top 90th percentile. See Drew Desilver, “For Most Workers, Real Wages Have Barely Budged for Decades,” Pew Research Center (October 9, 2014), www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2014/10/09/for-most-workers-real-wages-hav… and in 2014, writes the New York Times, corporate profits are at their highest level since 1929 and employee compensation at its lowest level in 65 years. See Floyd Norris, “Corporate Profits Grow and Wages Slide,” New York Times (April 4, 2014); Drew Desilver, “Who’s Poor in America? 50 Years into the ‘War on Poverty’ a Data Portrait,” Pew Research Center (January 13, 2014).

29. King, Where Do We Go from Here, 190.

30. King, Where Do We Go from Here, 190.

31. King, Where Do We Go from Here, 197.

32. King, Where Do We Go from Here, 199.

33. King, Where Do We Go from Here, 73.

34. King, Where Do We Go from Here, 76.

35. King, Where Do We Go from Here, 79.

36. King, Where Do We Go from Here, 90.

37. King, Where Do We Go from Here, 173.

38. King, Where Do We Go from Here, 171-172.

39. King, Where Do We Go from Here, 172.

40. King, Where Do We Go from Here, 172.

41. King, Where Do We Go from Here, 92.

42. King, Where Do We Go from Here, 172.

43. King, Where Do We Go from Here, 172-173.

44. King, Where Do We Go from Here, 183.

45. Paul Le Blanc and Michael D. Yates, A Freedom Budget for All Americans: Recapturing the Promise of the Civil Rights Movement in the Struggle for Economic Justice (Monthly Review Press, 2013).

46. Loic Wacquant, “From Slavery to Mass Incarceration,” New Left Review (no. 13, Jan/Feb 2002), 41-60; Mike Davis, Planet of Slums (Verso, 2007).

47. King, Why We Can’t Wait, 55.

Leave a Reply