The PRI is back—and the left is in disarray.

Enrique Peña Nieto of the Institutional Revolutionary Party (PRI) won the Mexican presidential election of 2012, with a plurality of 38 percent of the vote, returning to power the party that for 71 years ruled Mexico as a one-party state. His victory was largely a result of failures of out-going President Felipe Calderón of the National Action Party (PAN) who led the nation into a war with the drug cartels that took 60,000 lives, persecuted independent unions, and presided over a stagnating economy that grew less than 2 percent over a decade. With the Mexican financial and corporate elite throwing its weight behind him, and the major media promoting him, the youthful Peña Nieto campaigned and won as the leader of a new PRI promising democracy and reform.

Andrés Manuel López Obrador, presidential candidate of the left in 2006 and again in July of 2012, has once again refused to recognize the decision of the Electoral Tribunal which upheld the victory of Peña Nieto. Contending that the PRI bought millions of votes, “trafficking with the poverty of the people,” López Obrador promises to continue a peaceful struggle to rid the country of the current government. Standing before hundreds of thousands of his supporters in the Zócalo or Plaza of the Constitution in the heart of Mexico City on September 10, thanking the 16 million Mexicans who had voted for him as a “decision to abolish the actual regime of corruption, injustice and privilege,” he announced that he was leaving the Progressive Coalition, made up of his Party of the Democratic Revolution (PRD), the Workers Party, and the Citizens Movement, and that his campaign organization, the Movement for National Regeneration or MORENA would continue the fight for the “moral regeneration” of Mexico.[1] López Obrador’s decision to build his movement and apparently to create a new political party has led to fear that Mexico’s already fragmented left—in addition to the three existing left parties in Congress there are other extra-parliamentary parties and armed movements—could be weakened even more. Nor is it clear how his decision to turn MORENA into a political party would contribute to the tasks of rebuilding the labor and social movements.

Not a Return to the Past

The victory of Enrique Peña Nieto, a man notorious for his repression of a poor people’s movement in the town of Atenco when he was governor of the State of Mexico and known as the public face of the country’s most notoriously corrupt party, represents a defeat not only for the left, but for democracy, decency and social justice in Mexico. But it does not represent a return to the one-party state of the past. Too much has changed in the last several decades to make possible the recreation of the powerful state party of the past. The end of the national economic model, the greater involvement of Mexico in manufacturing for the U.S. and world economy, the sell-off of state industries, the weakening of the industrial unions, the decline in the size of the peasantry, the increase in urbanization, the role of the modern media, and the growth in the power of the rival parties that have actually held power at the national or state level have all undermined the bases of the old political machine.

The PRI, no longer so much a nationalist state party as a purely capitalist party, will push a conservative, pro-business agenda—coinciding in large measure with that of the PAN—calling for the privatization of energy, labor law “reform,” and regressive tax policies. The first item on the agenda is labor law reform which Calderón has now placed on fast track. The proposed reforms would render it virtually impossible to organize genuine unions, make it even more difficult than it already is to strike, and allow employers to subcontract and to hire temporary and part-time workers, practices now prohibited.

The Election Challenge Denied

The election was not entirely free and fair, though that comes as no surprise given the country’s well-deserved reputation for corruption at all levels and the experience of the controversial elections of 1988 and 2006 that several studies suggest were stolen. There is, however, no crisis of legitimacy as López Obrador has suggested. While the Televisa network, representing half the national TV duopoly, unfairly favored Enrique Peña Nieto, and though his party may have spent beyond the legal limits and may have engaged in vote-buying and other electoral fraud, such as inflated ballot counts, the government’s Electoral Tribunal ruled that all of López Obrador’s claims were “insufficient and inconclusive” as well as “vague, generic, and imprecise,” and concluded that such minor irregularities as there may have been would not have affected the outcome of the election which was won by more than three million votes. Most of the public and most independent observers appear to concur with that decision, recognizing that, contrary to López Obrador’s claims, the PRI could not have carried out vote-buying or fraudulent counting on a scale of millions. The notion that millions of Mexicans, however poor, would have sold their votes for as little as $10 and as much as $50, is not only insulting to the citizenry, but for logistical reasons beyond credibility on such a massive scale.[2]

The charge made by López Obrador and by the student movement IAm132, that Televisa violated Mexican election law in its overt support for Peña Nieto was no doubt true. Yet the process was really very typical of elections today in much of the world, with big corporations and the news media guiding voters in making choices, usually between two capitalist parties, or in Mexico’s case between three. Even so, unless we are prepared to deny voters any integrity, intelligence or free will in the electoral process, we have to recognize most voters chose to vote for the handsome young candidate of an infamously corrupt party rather than for López Obrador, the white-haired champion of the electoral left, a left also known for corruption and internecine warfare, because they thought the former would better represent them.

While the Mexican people may not whole heartedly believe in the legitimacy of this election, with their typical cynicism about politicians, parties, and the government, they by and large accept the PRI’s victory. We should also consider that many in Mexico, after all, have historically seen the PRI as both authoritarian, repressive, and corrupt and on the left in more or less the same sense that López Obrador is, that is, likely to use power to do something to improve the conditions of the majority. The Mexican people had had their fill of Felipe Calderón and his National Action Party, and, rejecting that party’s candidate, Vázquez Mota, turned to a party they thought would better represent their interests, and to most it seemed that that party was the PRI. The voters may not have recognized the degree to which the old PRI is dead and the new PRI is the party of business.

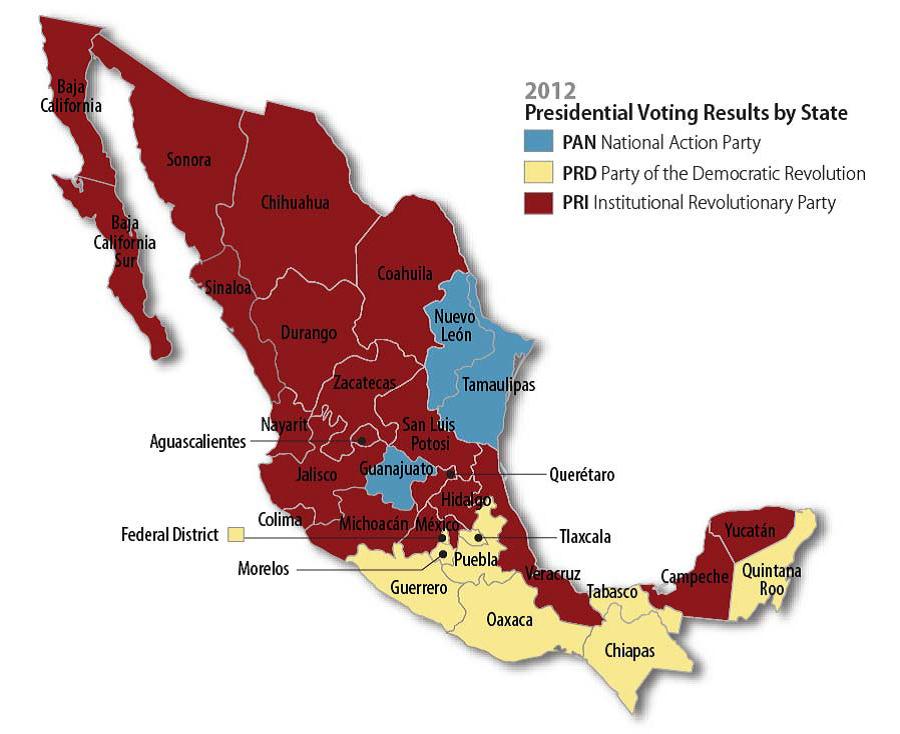

The Mixed Results: The PRD Remains a Force

While the PRI won the presidency, the PRD remains a force in Mexican politics, having captured Mexico City and many new congressional seats. The statistics in the presidential, congressional and state elections provide a complex picture of Mexico’s kaleidoscopic political voting patterns. With 63.02% of registered voters participating in this election, Peña Nieto received 38.2 percent of the vote and López Obrador 31.6 percent, with a 6.6 percent difference between the two, equivalent to 3.3 million votes. Josefina Vázquez Mota, candidate of the rightwing PAN received 26 percent of the vote. Peña Nieto, his victory having been upheld by the Tribunal on August 31, will take office on December 1, returning to power the party that ruled Mexico continuously from 1929 to 2000 through notoriously authoritarian, corrupt, and often violent methods.

Mexico’s 2012 Presidential Election Results: Party Preferences by State

Source: Mexico’s Federal Electoral Institute (IFE). Prepared by CRS Graphics

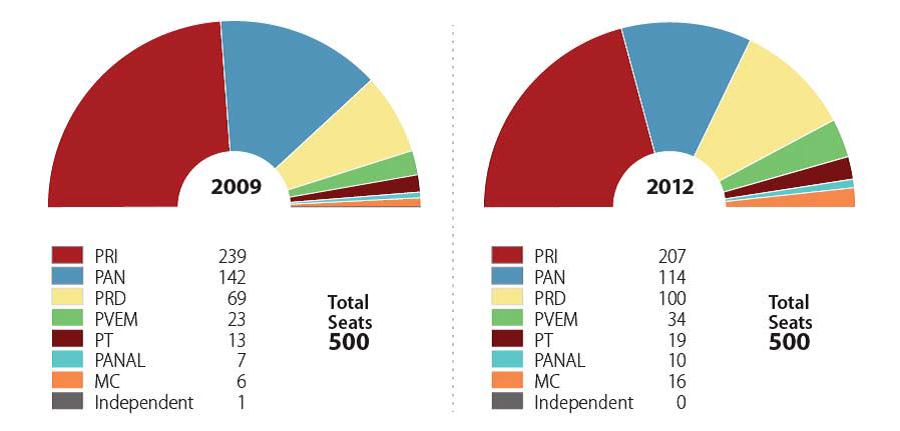

In the Congress, the PRI and its satellite, the Green Party (PEVM) will have 241 of 500 seats in the lower house, the Chamber of Deputies, while the PAN will have 114 seats, giving the two conservative parties together a majority. The PRD is not by any means irrelevant; on the contrary it has significant political power in Mexico City and in the congress. The PRD candidate for mayor of Mexico City, Miguel Ángel Mancera, a social liberal in the style of his predecessor Marcelo Ebrard, won election with 64% of the vote against 20% for the PRI candidate: A simply smashing victory for the center-left. At the same time, the PRD and its coalition partners, the Workers Party (PT) and the Citizens Movement (MC), made remarkable gains in the lower house, increasing its representatives from 88 to 135. Looked at one way, López Obrador won 31.6 percent of the vote while the PRD’s representatives claimed only 20 percent of congressional lower house seats. But relative to the previous election, López Obrador’s percentage stayed about the same, while the PRD had a 45 percent increase in congressional representatives.

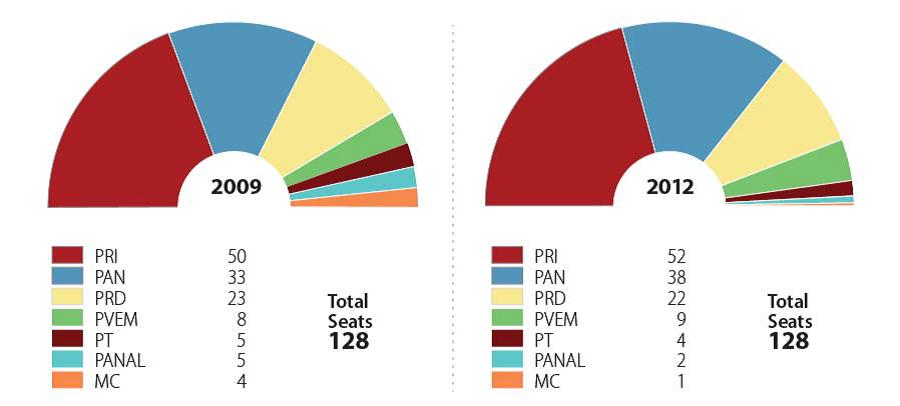

Senate Composition by Party

Source: For 2009, figures are from the Mexican Senate. For 2012, figures are from IFE. Chart from CRS.

Chamber of Deputies Composition by Party

Source: For 2009, figures are from the Mexican Chamber of Deputies. For 2012, figures are from IFE. Chart by CRS.

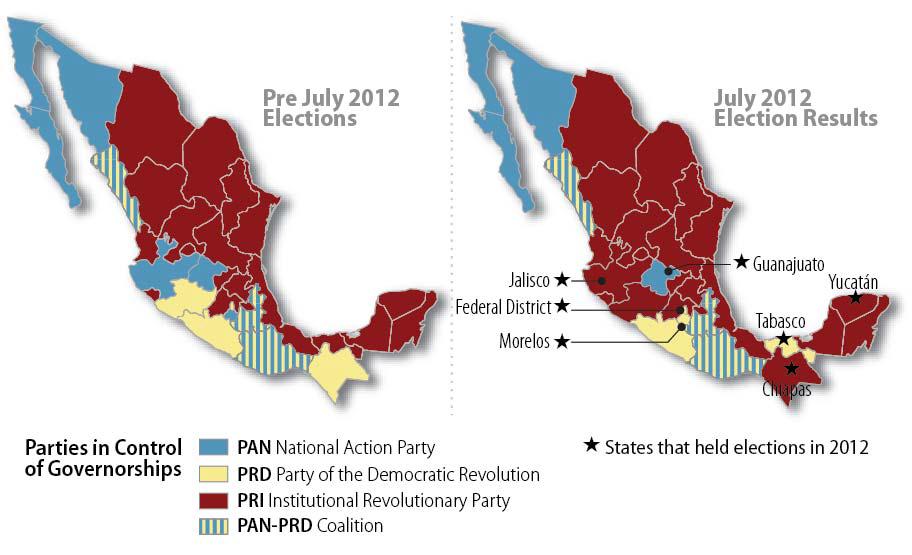

The Governorships

At the state level, however, the PRI’s powerful patronage organizations either survived the end of its national rule in 2000 or have been rebuilt since, and they made it the force to be reckoned with. While the PRD won the mayoralty of Mexico City (larger than most states in population) and the governorships of Tabasco and Morelos, it lost the governor’s race in Chiapas, and overall the PRI is now dominant in the states. The PRI holds governorship in 19 states, while the PAN holds 8, and the PRD only four and the Federal District.[3] Most Mexicans have voted at the state level—perhaps because that is where patronage machines provide the most direct and immediate benefits to their political clients—to live under the rule of the PRI. The election results suggest that political power in Mexico has become at best democratically divided among the parties, or more realistically fragmented among the competing parties and politicians. They also suggest that the country remains geographically split between the more prosperous North where the PRI or PAN generally hold power and the poorer South where the PRD does well.

Mexico’s 2012 Gubernatorial Election Results

Source: Mexico’s Federal Electoral Institute (IFE). Prepared by CRS Graphics.

A Leftist Strategy Tested in the Election

No one would deny, I think, that López Obrador was the candidate of a capitalist party, the PRD, and that his campaign this time was more moderate than in 2006. He dropped his earlier election motto, “For the good of all, the poor first” substituting for it the vapid slogan “loving republic.” He continued to defend the nationalized petroleum and energy industries, but this time he appealed to business and attempted vainly to charm the media by suggesting that he was a moderate, not a radical. He built as an extension of his own personality his top-down campaign organization, MORENA, which represented a multi-class coalition, though he failed virtually completely to find representation from the banks and corporations, so that it was preponderantly a middle class, working class, and peasant movement. Most of Mexico’s left, excepting the Zapatistas who eschew all electoral activity, joined MORENA (not as organizations but as individuals) and backed López Obrador. MORENA represented a modern Mexican popular front, that is, a bourgeois party with radical rhetoric and working class support.

What about the revolutionary left, or that wing of it which believes in participation in elections but rejects capitalist parties? The Revolutionary Workers Party (PRT), affiliated with the Fourth International, together with some Maoist organizations, worked with the Mexican Electrical Workers Union (SME) and other unions and social movement to create the Political Organization of the People and the Workers (OPT). The idea was that the OPT would avoid the pitfalls of popular front politics, allow workers, leftists, and movement activists to vote for López Obrador for president along with leftist labor candidates on the OPT line. At the same time, the campaign organized by this party would lay the basis for a workers’ party in the future. After López Obrador, the leading figure on the OPT ticket was the candidate for representative, Martín Esparza, both the elected leader and the most prominent public spokesperson of the electrical workers who had been fighting for their jobs for two years. But he too lost his election. The defeat of Esparza, and of other union officials on the left such as Senate candidate Francisco Hernández Juárez, longtime head of the Mexican Telephone Workers Union (STRM) and candidate of the PRD, suggests that there was no popular support for the idea of a workers’ party.

López Obrador Rejects Decision

López Obrador, has refused to accept the Tribunal’s ruling just as he did in 2006, accusing the Televisa television network of unfairly and illegally aiding Peña Nieto, charging the PRI with buying votes with supermarket gift cards, and faulting the Electoral Institute for failing to prevent those and other irregularities. When López Obrador lost in 2006 to Felipe Calderón of the PAN by a difference of 243,934 votes or just 0.58% of the total votes cast, his followers numbering between 500,000 and three million people filled the squares of Mexico City and blocked major boulevards for 47 days. Recognizing that the massive demonstrations of 2006 alienated many upper and middle class citizens and also that given the results it is unlikely that such protests could be organized this year, López Obrador and the IAm132 movement have so far declined to attempt to organize such a massive civil disobedience movement—though that could still happen.

The election poses numerable problems for the Mexican left. The IAm132 movement which arose so quickly just before the election, manifesting itself so creatively in protests against Televisa and Peña Nieto across the country, seemed to disperse just as rapidly. Some of the more independent labor unions, such as the Miners and Metal Workers, declined to join protests against the legitimacy of the election, apparently looking to see if after years of attack by Calderón and the PAN they might make peace with the new president and the PRI. López Obrador’s decision to transform MORENA into a stronger social movement and a new political party threatens to create political chaos on the electoral left, while it is not clear how that decision to build his populist organization would contribute to building a broad democratic left or increasing the power of working people in Mexican politics. The left stands in disarray in the face of the return to power of the PRI.

Notes

- López Obrador, “Mensaje íntegro de Andrés Manuel López Obrador en el Zócalo,” La Jornada, Sept. 10, 2012.

- For discussions of the effect of fraud on the Mexican election, see: Mark Weisbrod, “Irregularities reveal Mexico’s election far from fair”; Joshua Tucker, “Could the PRI have bought its electoral result in the 2012 Mexican election? Probably Not”; James Cockcroft, “The Mexican Elite will not allow A López Obrador to be President,” The Real News; and Phillip L. Russell, “Who Won the Mexican Election?,” Truth Out.

- For an overview of the election in greater detail, see here, and Clare Ribando Seelke, “Mexico’s 2012 Elections,” (U.S.) Congressional Research Service, Sept. 4, 2012. Also see this excellent summary: Harley Shaiken, "Return of the PRI: How did this happen? What does it mean for Mexico?"

Leave a Reply