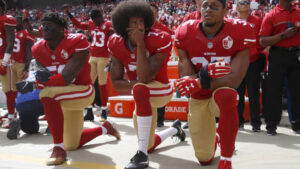

Dave Zirin is sports editor for The Nation, host of the weekly show Edge of Sports on SiriusXM Radio, and a columnist for SLAM Magazine and The Progressive. He was named one of Utne Reader’s “50 Visionaries Who Are Changing Our World,” and was called “the best sportswriter in the United States,” by Robert Lipsyte. Zirin is the author of ten books dealing with the politics of sports. His latest is The Kaepernick Effect (The New Press, 2021), which chronicles the impact of former San Francisco 49ers quarterback Colin Kaepernick’s act of taking a knee to protest police killings of Black people.

Dave Zirin is sports editor for The Nation, host of the weekly show Edge of Sports on SiriusXM Radio, and a columnist for SLAM Magazine and The Progressive. He was named one of Utne Reader’s “50 Visionaries Who Are Changing Our World,” and was called “the best sportswriter in the United States,” by Robert Lipsyte. Zirin is the author of ten books dealing with the politics of sports. His latest is The Kaepernick Effect (The New Press, 2021), which chronicles the impact of former San Francisco 49ers quarterback Colin Kaepernick’s act of taking a knee to protest police killings of Black people.

New Politics co-editor Phil Gasper interviewed Zirin in November 2021. The interview was subsequently transcribed and lightly edited.

Phil Gasper for New Politics: Well, great to see you, Dave. Let’s start by talking about your new book, The Kaepernick Effect. What motivated you to take that on as a project?

Dave Zirin: Well, it started as a conversation with John Carlos, the 1968 Olympian who, of course, raised his fist on the medal stand in Mexico. And John made a very offhand comment to me about young people who raised their fists at sporting events after he and Tommy Smith did so at those Olympics. And that immediately sent me spinning a little bit. I was wondering who these people were, and what happened to them, and what happened between them and their coaches, and was there a backlash? Was it similar to what young people had faced in this country who took a knee after Colin Kaepernick?

So, the parallel immediately struck me because I’ve written a bunch of these one-off stories about young people who have taken a knee, for The Nation. And it got me to thinking that, my goodness, you know, we don’t really have anything that looks at this in its totality, that looks at this as what I think it was, which was a national movement, even if it didn’t organize itself as such or know of itself by that name. I mean, you could call it an unconscious mass movement in a national movement, as well.

And I was thinking about how history is often recorded. I thought about people like Howard Zinn and how they wrote history, and Studs Terkel, and about how one of their great contributions was that they preserved voices that otherwise would not have been preserved. And I thought, given everything we know about, first of all, how history is taught in this country—of course, it’s a history of great people, normally men, who pull the levers—and also given the way our society operates on the basis of this kind of hyperactive celebrity culture, I was worried that all these stories were going to get forgotten and were going to get thrown down the memory hole. And if people remembered anything about this last period, it would be just a stale picture of Colin Kaepernick with a knee. And if we’re lucky, maybe there would be a caption explaining why he was doing what he was doing. So, that was the motivator.

But then as I was writing the book, of course, the summer of 2020 happens. The police murder of George Floyd happens, and that changed the way I was thinking about the entire project. Because at that point I went back, and I got in touch with dozens of people who I’d interviewed for the book, and they were all either in the streets or organizing people to get in the streets. And that really made me realize that these young people really laid the groundwork for what we were seeing in 2020, which, let’s remember, were the largest set of demonstrations in the history of the United States. And I think sometimes we elide that truth. I mean, these were demonstrations that took place in all fifty states. It was a remarkable explosion of anti-racist consciousness. And the groundwork for that … These things don’t come out of nowhere, of course. And I feel like while many roads may have led us to that point—many, many, many roads—one of those roads, at least, runs through the athletic fields of the United States. And I felt that story really, truly needed to be told.

And now that the book is out, I’m also seeing what these young people did as really a canary in the coal mine. Everything we’re seeing right now with these ridiculous so-called anti-CRT [Critical Race Theory] debates that are being used to attack public education, attack teachers, and to attack even the very idea of speaking about anti-racism or about the history of the United States, I think it’s the backlash that these young people received for taking a knee during the anthem in their communities. If we had paid attention to the political tenor of that backlash, we would have gotten quite the sneak preview for everything we’re seeing in 2021.

NP: And of course, Kaepernick’s protest itself emerged from what happened before, because we’d had several years of Black Lives Matter protests—up and down, but that’s got a history now. So, when he took the knee in 2016, that was coming out of what had already been happening in many communities around the country.

DZ: Yes, I mean, and that’s why I’ll always argue that for people interested in this issue of sports protests, they have to understand that it always starts off the athletic field and not on the athletic field. It always starts from what’s in the streets, then ricochets onto the field. And then people on the athletic field—you think about someone like Muhammad Ali in the 1960s or Billie Jean King—can have the capacity through using their sports platform to then shape what’s taking place off the field. But it always starts in the streets.

And in Colin Kaepernick’s case, the reason why he sat and then took a knee in the first place was because of the police murders of Philando Castile and Alton Sterling, both of which produced viral videos during that summer of 2016 and had already led to athletic protest in the WNBA. But what Colin Kaepernick did, what he gave the movement, what Colin Kaepernick did that was different from what we had seen before, even in the world of sports protest, was that he provided a symbol for visible dissent that anybody could replicate. That very simple act of taking a knee during the anthem, that was Colin Kaepernick’s gift to the struggle, and so many people took that baton and ran with it.

NP: Yeah, through the following couple of years, at least, and then again in 2020 with the protests around the murder of George Floyd.

DZ: Part of it also is, I remember getting in conversations and arguments with people in 2018, 2019 where people were quite distressed about the state of the movement. And the argument that I had was two-fold. I mean, first, you read histories of the civil rights movement. You’ve got King and others in the late 50s wondering if the movement had run its course, right? And we can’t forget that. And then the second thing is, I would also point to these protests saying, okay, you’re saying nothing’s happening because there’s no national march in Washington. And maybe people who have been identified as organizational leaders seemed demoralized or distracted, or onto their own vanity projects in some cases. But if you look at sports, if you look at these athletic fields, you’re still seeing the movement play itself out, even in those years that other people were describing as somewhat parched.

NP: Right. Movements go up and down. So, we saw a high point in 2020. But today, 2021 going into 2022, where do you think that movement is now? Are these protests continuing in some form? Has the taking-a-knee form of the protest become passé? I mean, it’s certainly been co-opted by Democratic Party politicians, even police departments having their photos taken, kneeling. Is it moving in new directions now, or is this still a form that it’s taking in different places?

DZ: It’s moving in multiple directions, and the mere fact that there’s been so many efforts to appropriate it by Democratic Party officials, even by police, as you mentioned, or by entire teams that do it as a kind of team activity—they do it together, with the acceptance or even approval or even encouragement of management—I mean, all of that, frankly, is a tribute to its power, because this society only appropriates things, or commodifies dissent, when it’s gotten too big to ignore or destroy. Because that’s always the first instinct—you destroy the dissent, and you destroy the dissenters. And on both fronts, both in terms of Colin Kaepernick and the act of taking a knee, they failed to do so. So, then the next effort becomes one of appropriation.

So, Colin Kaepernick does his commercial for Nike and now he’s got his Netflix special—which is frankly very good. (And make sure we keep that in the interview, that I actually think it’s very, very good.) But it’s just what you do when you can’t completely bury and destroy somebody, you attempt to commodify. And there’s no way they’ve been able to completely squelch the act, taking a knee.

Two points. First is, when these police officers take a knee or Nancy Pelosi, they’re not doing it during the national anthem. And that’s such an important part of the piece. They do it more as an act of anti-racist prayer, and it’s all very, very performative. Whether it’s in the hands of Pelosi or the police, I would argue it’s equally performative. But when it’s done during the anthem, it has this very direct challenge to this country. And it’s saying, either… At most it’s saying—to speak most generously—that there’s a gap between what this country stands for and what it actually delivers, particularly to communities of color. But you take it to an even bigger level, it’s saying that this country is actually a sham when it says, “Land of the Free, Home of the Brave” when, as Colin Kaepernick said, people are dead in the street and police are getting away with murder.

NP: You mentioned the teams, whole teams taking the knee and that’s kind of double-edged, because it could be management co-optation, but also the pressure has come from the players themselves. I mean, last year with the NBA, almost the entire NBA was taking the knee before games. And that seemed to come, from what I was seeing, from the anger and activism of some key leaders among NBA players.

DZ: No, that’s true, but it was also seen as a way for the NBA to try to ingest the dissent that was already there. You’ll cut with it instead of trying to squelch it.

NP: Yeah. Very soon they saw that as their best move, right?

DZ: Yeah, their best strategic move. And the players then, last August, moved past it very quickly, after the police shooting of Jacob Blake in Kenosha. They said, well, we’re actually going to go on strike. We’re not going to play at all. We’re going to cancel playoff games. And that started with the Milwaukee Bucks. And there were several sports columnists who wrote that the Milwaukee Bucks’ stand in solidarity cost them the NBA Championship because they were too distracted to play basketball. But nobody said—or some of us said, but none of these same writers, let me put it like that, said—when the Bucks actually won the championship in the summer of 2021, that their actions the previous year had brought the team closer together, which a lot of the players said it did.

So, I mean, not that it really matters if a team wins or loses based on this protest, but I do think it’s interesting that the point of sports, which is of course to win the game, can often be used by the right and by the center as a way to try to squelch protests. I mean, that’s why when we think of some of the great political athletes in history, it’s not a coincidence that people like Ali or Arthur Ashe or King, that they all played in individual sports, not in team sports, because the team sport makeup can be extremely conservatizing. Which is why the people in the book, especially the young people who took a knee, all playing on sports teams, are all the more remarkable, because they’re going against a culture that has been built up for a hundred and fifty years that says you do not do that.

NP: And this has had an international impact as well, because taking a knee spread to international soccer, for instance. The English team was taking a knee in the lead up to the European Championships. And actually, it was condoned by their manager, who was a big supporter of it and played a big role in this happening. But they were getting pushback from the fans. I mean, there’s an enormous amount of racism among football fans in England and in Europe. And this was a kind of way of standing with Black players and those who take the brunt of this. So that’s a kind of interesting phenomenon as well, the way in which it has not just been a U.S. phenomenon, it’s become this much, much more global act of some kind of resistance. I mean, I don’t know how much resistance we can talk about, but it’s certainly an act of anti-racist solidarity, which is not to be sniffed at.

DZ: Yeah. I was interviewed by an Irish publication for the book, and I sort of pooh-poohed those kinds of demonstrations over there in Europe. The journalist really did push back on me and said if you were more cognizant of how deep the racism among fans runs, you would see that taking a knee, even if it is management approved or all the rest of it, is really like a challenge to those fans to change. And that’s very different from somebody in Brunswick, Ohio, or Beaumont, Texas, taking a knee by themselves to challenge the racism in their small town or community. But just because it’s different, it doesn’t mean it’s absent of value. And it seems to me after a further study that it matters that they’re doing this in Western Europe because it’s about players trying to really change the culture of the entire sport.

NP: And then you’ve got—I know this is true in the UK and probably in some other places as well—anti-racist, anti-fascist organizing going on among the fans. So, I mean, there’s polarization. You’ve got racist fans. You’ve also got anti-racist fans. And I don’t know if this is true in the United States, but certainly in England there are organizations that organize soccer fans to oppose racism, to work collectively around some of these issues, which is a very interesting phenomenon, too.

DZ: Yes, some of them, I mean, go back 15, 20 years. The soccer fans organizing against racism, players wearing bracelets of solidarity, all kinds of things of that nature. And then there have been players of African and West Indian descent who have made a political impact. People like Marcus Rashford in the UK, who has played a remarkable role around the issue of hunger during the pandemic and applying not just his celebrity, but really organizing public pressure to change laws and to move laws through parliament that Boris Johnson has had to not only reluctantly sign, but heartily endorse. And it’s been through Rashford’s efforts. I know when Rashford was one of the players blamed for the most recent England debacle,* that’s when his teammates really stepped forward, and several of them did talk about how it’s connected to racism in the sport. It’s pernicious. And that act of taking a knee is a challenge to a sector of fans.

NP: Let’s talk about another form of oppression that is intersecting with sport in a big way, which is the attack on trans people. You’ve written quite a bit about this. It’s intensifying in the United States and in many other places. Some state governments have particularly focused on the rights of trans kids in schools. We’ve just now got a Texas law that prevents them from playing on sports teams of their gender. You’re only allowed to play on the team of your biological sex at birth. Can you comment a little bit about this, both in terms of the attack, but also what kind of resistance there is, or what kind of organizing is happening around this issue?

DZ: Well, a lot of the organizing that I see around it is happening on the school-by-school level, teachers, parents, a lot of people trying to fight back legislatively, lobbying. The ACLU has several rather brilliant legal minds trying to work on this, and their shift has been a welcome one. But has it translated into a movement? That’s unfortunately not something we’re seeing. And has it translated into anything that we’re seeing in the world of sports? Well, it should, frankly, because they’re using sports as a wedge and as a cudgel to divide people, to divide what our side should be. And so, they’ve pulled onto their side prominent LGBTQ athletes like Martina Navratilova, who will say things like they’re for trans rights but against trans people participating in the sport of their gender.

And it’s been a successful wedge in a way that, say, the bathroom bills were not. Because they’ve been going after trans people for as long as trans people have asserted their visibility, and bathrooms didn’t work. So, they’re starting now with sports, and they’re finding much more success with it, and that’s scary. The amount of success they’re finding is scary. But I’m just very confident, I’ve got to tell you Phil, in this generation of people that are coming up right now, the people I interviewed for the book, the people my daughter’s age. I’m just very confident that they’re not going to settle for the things that perhaps other generations were willing to settle for and that they’re not going to abandon their trans friends because of some off-the-beam Texas politicians and their allies. So, I mean, there’s a fight brewing, but I feel confident in saying that the fight is going to be joined.

NP: So, you write about the intersection of sports and politics from a number of different angles. One of them is sport as big business, which of course it is. And it doesn’t get any bigger business than the Olympics. So, we just had the postponed Summer Olympics, and now we’re heading to Beijing for the Winter Olympics. There are big issues around this involving the risks of major sporting events while the pandemic is still going on, but also these questions about human rights and what’s going on in the countries that are hosting these events. I mean, after the Winter Olympics, we’re going to have the World Cup in Qatar, which also raises massive human rights issues. So, what are your thoughts about these big international events and the questions they are raising?

DZ: Well, it’s such an exposure of these events when they nestle in places like Beijing or Qatar, because what they’re really saying is that there is so much domestic opposition to the Olympics, to the World Cup in recent years, and to the spending priorities and the security priorities that these events demand, the displacement priorities, that they really have to find autocracies and dictatorships to host these events.

And they like to say, the International Olympic Committee, FIFA, that—and this is how they argue against the criticism that you’re supporting an abusively anti-human regime, a regime that flouts human rights—they say, well by going there, we’re actually engaging with them and we’re making them more just, more democratic, just by our presence. It’s a very Kiplingesque view as well. It’s like we’re bringing Western democracy and Western thought to these lands of dictatorship. But what you find instead is that when these events go to places like Rio or like Los Angeles, it’s not that they’ve made Beijing a little more like the Western world, it’s more like they’re making bourgeois democracies more like Beijing. Because when they show up to places, it’s hyper-militarism, it’s squelching of free speech, it’s squelching of free movement. It’s all sorts of small autocratic leanings.

NP: It’s clearing out whole neighborhoods as well, right?

DZ: Yes, exactly.

NP: Displacement of the poor and the homeless and anybody who’s in their way.

DZ: When I was in Tokyo, before the pandemic, summer of 2019, just sort of examining the Olympic organizing and investigations, I actually spoke to people who had been displaced for these 2020 games, who were elderly, who had also been displaced in 1964 for those Tokyo Olympics. So, their lives have effectively been bookended by being displaced for the Olympic Games in Tokyo. So that’s your Olympic Legacy.

NP: I take it you won’t be going to Beijing next year.

DZ: No. I probably could but I wouldn’t, and, honestly, it’s more about personal safety. I was denied going in ’08—they rejected me, as they rejected a lot of journalists from coming into the country. People I know who went to Beijing, who I interviewed, who attempted to unfurl a Tibetan flag on the street in front of the Olympic Stadium, got picked up and thrown into a van within thirty seconds and were put through a very frightening ordeal that involved being blindfolded. These are U.S. citizens, and they were eventually deported after getting the shit scared out of them. So, this is nothing I want to do, and I’m not going to go. And I think having these kinds of mega events in a time of Covid is just unbelievably irresponsible. I think what was done to Tokyo—a very, very heavily concentrated city with a very, very low vaccination rate—was abominable, and it led to the spasms of spreading of the virus in Tokyo.

NP: Yeah, and we shall see what the situation is like next year, but it’s certainly not going to be back to normal.

DZ: Yeah, and our hopes of getting to anywhere close to normality lie in not doing events like the Beijing Winter Olympics. We’re actually running counter to what we need to be doing if we want to emerge from this.

NP: I want to ask you about something that I don’t know what the connection with sport is, but it’s such a big issue right now: the climate crisis. From my perspective, that’s the biggest crisis that we’re facing. So, I’m wondering, have you written about that? Is there an intersection with what’s going on in the sports world? That’s one area in which we are beginning to see protests reemerge. So, what are your thoughts about that connection?

DZ: I certainly agree with you that it is the issue that existentially surrounds every single other issue that we work around and care about. The UN has something that a lot of athletes are involved in called the Sports for Climate Action Framework—S4CA, for folks who want to look that up. To me, I was reading it over and it speaks to how kind of desperate we are to find some method—because what is sports really going to do to deal with this? I mean, one of the organizations that signed on to this is the International Olympic Committee, an organization that leaves the heaviest possible carbon footprint wherever it goes and talks all the time about having a green Olympics. Like look at this new billion-dollar stadium we built—the gutters take rainwater and process it so it becomes freshwater that’s then recirculated through the system. I’ve seen stadiums like that and I’m like, what about the billion dollars that went into building this stadium? What kind of carbon footprint did that leave to make your wonderful rain gutters?

What we see in terms of actual athletes doing work around this that’s not through these kinds of first-use channels—we’re not seeing it yet. But it’s hard to imagine that it’s not going to be discussed in Beijing, because having enough snow for these kinds of winter sports has lately required flying in snow and dumping it in different places, which leaves its own carbon footprint.

NP: Right. So, it’s experiencing the impact of climate change, and then you make it a little bit worse. You’re using these energy intensive methods to produce the conditions for winter sports. So, it’s ironic and kind of troubling the way that this is going.

DZ: But at least they signed onto a UN decree!

NP: What else is happening in 2022? Anything on the horizon?

DZ: I mean, some ideas, but just sitting with this book for a minute. I’ve got some stuff brewing. I thought about writing something, and I’m still thinking about it—it’s kind of weird sounding—but an exposé of the 1984 Olympics in Los Angeles.

NP: In preparation for the next LA Olympics?

DZ: Yeah, exactly. Because one of the things that has been used by the LA 2028 committee is this kind of very, very rose-colored memory of ’84 and what it meant to the city of Los Angeles, when they actually did a lot that would not fly today, I don’t think, like what they called the gangs sweeps and the very, very pointed attacks on Black and Brown communities by Daryl Gates and the Los Angeles Police Department, during a time when the cities were just starting to rumble over the importation of crack cocaine by our own government to pay for their dirty wars overseas. Oh, did I just slip that in there to our sports interview! But the point is, I think that there’s a lot there for us to talk about in terms of Los Angeles. And I’m trying to think of something that would be useful for the LA 2028 activists, who are really impressive. They’ve been organizing ever since the bid idea came up. And they’ve done some terrific work out in Los Angeles.

NP: Excellent. Well, I hope you pursue that. I’m looking forward to seeing it and whatever else you are going to write about. Thank you so much.

Leave a Reply