On December 4, 2016, the Italian electorate was asked to vote on a government-proposed constitutional reform, and the vote dealt the government and Prime Minister Matteo Renzi’s plans a ringing blow. The referendum was a political gambit on which the PM bet everything, yet 59.1 percent of voters rejected the reform. Barely an hour after the polls closed, Renzi announced his resignation.

An observer unfamiliar with Italian politics may be baffled that what appears to be an arcane constitutional question engendered so much unexpected enthusiasm: With a record turnout, unlike anything in the last two decades, nearly 70 percent of eligible voters (65.5 percent if one counts Italians living abroad) cast their votes, as opposed to 34 percent in a 2001 referendum and 53.8 percent in 2006.1

Even more fascinating is the international interest in this vote. In an August 12 article, the Wall Street Journal drew a picture of Italy as a country with zero economic growth, a debt burden equal to 135 percent of GDP, and youth unemployment high above the Eurozone average, 36.5 percent versus 20.8 percent. It concluded that the Italian referendum was “especially vital—and arguably more important than the Brexit vote. … Success in the referendum on this issue should lead to greater stability for Italian governments which, in turn, should help the introduction of reforms that the Italian economy needs to boost potential growth.”2 The New York Times and the Financial Times concurred: “Italy badly needs a more efficient political system that allows for decisive economic reform.”3 The mainstream consensus was that, while the constitutional reform was an insufficient cure for one of the weakest economies in Europe, a Yes vote in the referendum was essential for the financial, economic, and political stability of the peninsula.4 The U.S. ambassador in Rome, John Philips, echoed a similar sentiment in early September: “All I can say from the American perspective is if it fails, those American companies that are coming to Italy—and Italy ranks right now eighth in investment in EU where it should be third or even second—it will be a big step backward in terms of attracting more foreign investment.”5 Yet as the likelihood grew of a win for the No vote, the international media—with The Economist in the lead—did a U-turn. And so did Brussels, as the polls closed, insisting that it was an “issue for Italians and not the European Union.”6

What accounts for this interest in an issue that seems to concern only the internal functioning of Italian political institutions? One theory that has gained ground is that the whole matter was due to Renzi’s tactical mistake, his decision to personalize the vote by threatening resignation if the referendum failed. But to see things this way requires a good deal of amnesia. In fact, the modifications that Renzi loudly promoted were the next step in a long assault on the constitution that started during the Silvio Berlusconi era, an assault whose practical translation in the realm of concrete politics was the dismantling of the Italian welfare state.

The Spirit of Neoliberalism Translated into Law

Indeed, at stake was the 1948 constitution. According to a May 2013 report issued by Wall-Street firm JPMorgan Chase, one of the structural causes of the recurring crises hitting southern European countries is the fact that their constitutions emerged from the fight against fascism and therefore carry the strong imprint of left-wing parties. The report, from a company indicted by the U.S. government for its role in the sub-prime mortgage crisis, goes on to blame these constitutions for “weak executives; weak central states relative to regions; constitutional protection of labor rights; consensus building systems which foster political clientalism; and the right to protest if unwelcome changes are made to the political status quo. The shortcomings of this political legacy have been revealed by the crisis.”7

Underneath the talk of the need to make the constitution more “agile” and “flexible,” and above all more compatible with the requirements of a neoliberal Europe, there were real attacks, not only on the letter, but on the spirit of the constitution, which, in the beautiful expression of its spiritual father, Piero Calamandrei, represented “the spirit of the resistance translated into law.” The modifications to the 1948 constitution connected to the new electoral law included reducing the Senate to an ancillary chamber of Parliament, appointed rather than elected by the people, and reducing the number of provinces in order to “contain institutional costs.” The object of these reforms was to strengthen executive power by essentially placing the state’s political institutions in the hands of one political force and its leader. The result would have been a more centralized power with less room for the political expression of the citizenry, at the very moment when measures of austerity keep raining down on a wounded country. The centralization would serve to insulate the stable continuation of capitalist globalization from popular discontent.

The No victory represents, therefore, a serious setback for the introduction of a form of government that is both authoritarian and anchored in a state of emergency. This victory was the fruit of an extraordinary mobilization of large sectors of Italian society, including civil-society movements, social centers, neighborhood associations, all the radical left, the left of the Democratic Party (notably, the left of its parliamentary group), trade unions (although the role of the trade union federation CGIL has been muted), the National Association of Italian Partisans (ANPI), and others.8 The battle waged in the last few months in favor of a No vote was therefore much more than merely an expression of anti-government feelings. Failing to fully understand this can lead to the mistake of accepting the reforms in principle, as if under different circumstances they would be supportable. In fact, those who mobilized against the reforms were defending popular sovereignty and the elementary democratic rights guaranteed by the constitution. To this was added the refrain that the goal should not be to reform the constitution but to insist on its full application. For, as militant anti-capitalist and historian Antonio Moscato put it, “For many decades now, the constitution is only being applied, at least in parts, when there is a radical movement of contestation from below—from the factories, the schools, the street.” This is notably the case with the protection of workers.9

‘I Take Full Responsibility for the Defeat’

Almost six of every ten Italian voters said No, massively rejecting the reform at the heart of Matteo Renzi’s political program and that of the alliance he forged with Silvio Berlusconi as soon as he took office in February 2014. Many blame Renzi for the error of making the referendum his chief political battle and staking his political future on it. And it is true that the campaign for the Yes vote pulled out all the stops, with massive propaganda in the streets, rallies, interviews, and televised debates. Yet few have noted that Italians have rejected not only Matteo Renzi, but also the policies he advocated and implemented in the 1,000 days of his term: the Job Act, which gave companies discretionary power over hiring and dismissing employees; the abolition of Article 18 of the labor code, called by Renzi an “ideological totem” of the 1970s, which forbade abusive dismissal; the wage cuts; the liberalization of labor and the concomitant privatization of public services as well as parts of the national heritage; not to mention the private-sector-friendly school reform.10

Renzi’s resignation is therefore the logical outcome of the growing disaffection of an Italian population undergoing massive impoverishment. This disaffection already made itself felt in the local administrative elections last June, in which the Democratic Party lost twelve administrative centers. Virginia Raggi and Chiara Appendino, two young women representing the Five Star Movement, won with large margins in Rome and Turin. Doubling down as the Democratic Party was losing steam, Renzi then dismissed those results as “local,” vowed to stay the course, and announced his intention to remain in office until 2023. Yet the Democratic Party’s political program is increasingly at odds with the daily experience of the overwhelming majority of Italians, especially the popular classes. In Rome, for example, Virginia Raggi won in working-class areas, whereas the Democratic candidate drew his support primarily from affluent neighborhoods.

The No of Revolt

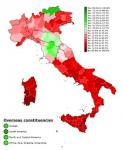

The No vote won throughout Italy, but with the largest margins in the South: 71.2 percent in Sicily, 72.5 percent in Sardinia, 68.4 percent in Campania, and 67.2 percent in Apulia. In the North, the highest No vote (61.8 percent) came in Venice, home to the Lega Nord (Northern League) of Matteo Salvini. Only three regions bucked the trend: Renzi’s home region Tuscany voted Yes with 52.4 percent, Emilia-Romagna with 50.3 percent, and Trentino with 57 percent. Unsurprisingly, Italians living abroad have also supported the constitutional reform with 60.24 percent voting Yes.11 As soon as the results came in, journalists noted the strongly political meaning of the vote: Voters wanted to punish the government. But who comprises this “people in revolt,” as the director of the bosses’ newspaper La Stampa called the No voters? According to the latest data, among the unemployed, the No vote won with over 70 percent, a significant result in a country with the very high official unemployment rate of 11.6 percent. With a 76-percent No vote, the self-employed also rejected the constitutional reforms. “Self-employed” is a rather vague category that can include shop owners, taxi drivers, farmers, entrepreneurs—many of whom cannot make ends meet today—as well as the large sector of those who “scrape by” outside formal employment. With 66 percent for the No, stay-at-home women are another group that voted massively against the reforms. They are best placed to recognize the effects of the food social gap, the growing gap between the food budgets of the rich and the poor. (In addition, women in Italy as elsewhere are over-represented among the unemployed.) According to Caterina Pasolini, over the past seven years, Italian families have reduced their spending on food by 12 percent on average, but the drop is nearly 19 percent for working-class families and over 28 percent for the unemployed. There is also regional difference, with a larger drop in the South (16.6 percent).12 The South is also where the unemployment rate is highest.

The No vote also won among younger people, who tend to be more exposed to the crisis. Over 61 percent in the 18-29 age group and 69 percent in the 30-44 age group rejected the constitutional reform, as well as 58 percent of students. The only age group that supported the reforms is retirees, including those residing outside the country, no doubt deeply influenced by statements made by the European authorities.

A Populist Vote?

The energetic campaign lead by Matteo Renzi and his government in support of a Yes vote had the support of an international effort to frighten voters with forecasts of the disastrous consequences Italy would suffer if the constitutional reforms were rejected. The government warned that a No vote would lead to a general collapse. To further heighten the drama, Renzi scheduled the referendum for December 4, the day of the presidential elections in Austria, where an extreme right-wing candidate appeared likely to win. All through the campaign, the Democratic Party, its leader, the markets, and the EU were incessantly ratcheting up fear. But the voters were not cowed. Some have seen in the vote a new expression of “populism”—by now a catch-all term—and in particular of the rise of the Five Star Movement (M5S), which had endorsed the No vote. In fact, the No had the explicit backing of an overwhelming majority of Italy’s political parties. And the voters followed on both sides of the left-right divide. Eighty-eight percent of Lega Nord and M5S voters voted No. On the left, 68 percent of the voters of Sinistra Italiana (SI), Sinistra Ecologia e Libertá (SEL), and the radical left voted No. But the No vote also received support from 15 percent of the voters of the Democratic Party. The undecided also played a role, with 60 percent of them eventually falling to the No side. In a sign of the times, and of the end of what Alberto Meloni called “the political culture of the long and peaceful after-the-war,” the rage and the determination of the Italians found expression in this vote well beyond the parties that recommended No. This is no doubt why the political class has come to fear the very idea of a referendum, considering it “an instrument for the dissolution of authority.”13

What Is to Be Done …

Rossana Rossanda, founder of the left-wing journal Il Manifesto, who called for rejecting the constitutional reform, admitted that “there is little enthusiasm for voting No because we find ourselves with strange bedfellows.” It is evident that the diverse constellation that supported the No will have trouble seizing the political opportunity created by the fall of the government.

Fortunately, the right is divided. The Lega Nord, probably soon to be rechristened Lega degli Italiani to better fit the national aspirations of Matteo Salvini’s party, is already pushing against the door to take advantage of the No result. Polls in mid-November gave the party 10 percent support among voters, which is five less than projections from June 2015, but the victory of the No vote may give Lega Nord electoral wings. Silvio Berlusconi’s Forza Italia, another party that sided with the No, is likely to receive about 12 percent of the votes.

But the key party set to advance in the next elections is M5S, which has become the standard-bearer of the opposition to Matteo Renzi. M5S spans a very broad spectrum of the Italian public, drawing voters from right, left, and center. Previously seen as the party of the young, the movement has recently increased its support among voters in the 35-55 age group. By winning the municipal elections in Rome and Turin, the party has proven itself—at least according to its leader Beppe Grillo—“capable of governing.”14 Grillo has missed few opportunities to reassure the political and economic people who count, with statements such as, “If M5S wins the elections, nothing will happen. … The markets have nothing to worry about.”

For the Democratic Party, the Lega Nord, and Forza Italia, M5S is therefore the party to beat. But the Five Star Movement is also an additional impediment to the deeply needed task of recomposing the left-of-the-left in Italy: Witness the appropriation of the central role of the local workers’ struggles by M5S during the last No assembly in Turin.

How can the left-of-the-left benefit from the No victory? This is the heart of the problem. No doubt the first order of the day is to hear the popular demand and call for the dissolution of Parliament and a quick return to the polls. But no less important is to take the measure of the vote and not fall for the media echo chamber. The constitutional question has not been forgotten during the debates. The opposition to the government also extends to the modifications in the legal framework of the Italian constitution. Contrary to Beppe Grillo’s assertion, voters have voted not only from the “gut,” but also from the head. It is impossible to deny the fact that the vote of December 4 was also the expression of a political will oriented to the future. And this political will, as says the last communiqué of the small radical left group Sinistra anticapitalista, can offer the opportunity for “the renewal of social mobilization and the struggles at the workplace, in the schools, the universities, in the defense of rights, of the environment, and for a better life and better jobs for the greatest number.”

Translated by Gabriel Ash.

The title of this essay comes from Article 1 of the Italian Constitution. A shorter version of this essay was published in Spanish on the website Viento Sur.

Footnotes

1. Repubblica, December 6, 2016.

2. Richard Barley, “Italy: At the Heart of Europe’s Growing Pains,” Wall Street Journal, August 12, 2016.

3. “Rome needs reform but stability is the priority,” Financial Times, December 1, 2016

4. Maria Salas Oraa, “Italia se convierte en el nuevo enfermo económico de Europa,” El Paìs, August 13, 2016.

5. Daniela Preziosi, “US Ambassador to Italy,” Il Manifesto. Global edition, September 14, 2016, ilmanifesto.global.

6. “Why Italy should vote No in its referendum,” The Economist, November 24, 2016.

7. J.P. Morgan, “The Euro area adjustment: about half way there,” Europe Economic Research, May 28, 2013.

8. Cinzia Arruzza, “Democracy Against Neoliberalism,” Jacobin, December 5, 2016.

9. Antonio Moscato, “Irresponsabili giochi di Guerra,” Movimento operaio, October 17, 2016.

10. Francesco Locantore, “La buona scuola liberista di Renzi,” Il marxismo libertario, September 5, 2014, ilmarxismolibertario.wordpress.com.

11. The data comes from Ilvo Diamanti, Repubblica, December 6, 2016.

12. Caterina Pasolini, “La crisi a tavola,” Repubblica, October 24, 2016.

13. Le Monde, December 5, 2016

14. beppegrillo.it

Leave a Reply