This article aims to show that dependency theory underlines vividly the problem of examining the logic of capital independent of Marx’s concept of value. It is impossible to completely understand the essence of Marx’s critique of political economy, especially a vision of an alternative to capitalism, without grasping value as distinct from exchange value. The distinction is of vital importance, since uprooting relations of exchange cannot itself eliminate the defining principle of capitalism: abstract labor, production for the sake of value. In the reflections that follow, I will argue that dependency theorists remained fixated upon the fetishized world of appearances, that is, exchange value, without penetrating into social relations of production. On the other hand, my intention with this article is to stimulate a discussion among revolutionary activists on the necessity of transcending abstract value production.

I.

The anti-colonial and anti-imperialist struggles that swept through Africa, Asia, and Latin America following World War II inspired the emergence of a diverse and heterodox set of theoretical schemas, collectively known as “dependency theory,” whose key texts deployed concepts borrowed from Marx and Lenin to offer a rival theory of imperialism. The general consensus among dependency theorists was that the process of global capitalist expansion generated development in its core locations (Western Europe, North America, and Japan) and underdevelopment (poverty) in its periphery locations (Africa, Asia, and Latin America). According to this perspective, the advance of the Western world was not the result of an inescapable whim of nature, but only made possible following an exogenous path of development, focusing on international trade, raw material extraction from colonies, and profits made by providing the world economy with financial services.

Dependency theory spanned the political spectrum: from the revolutionary socialist school of Andre Gunder Frank, Samir Amin, and Theotonio dos Santos to the bourgeois nationalist and social-democratic school of Arghiri Emmanuel, Fernando Henrique Cardoso, and Enzo Faletto. The founders of dependency theory aimed at examining the characteristics of peripheral states, which are conditioned by the development and expansion of another economy. The starting point, therefore, was relations with the external world, that is, divergent networks of international exchange. Drawing from this premise, dependency theorists argued that peripheral states are those that have historically been dependent on the export of primary commodities for the international market.

The central argument was that the interests of the core states lay in freezing the international division of labor so that peripheral states continued to be producers of primary commodities. For example, the destruction of the Indian textile industry by England in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries represents the general attitude of metropolitan corporations toward industry in the satellites. Therefore, it was believed that the interests of companies exporting primary commodities to the metropole did not lie with general economic development of the satellites. This led the so-called “dependentistas” to believe that little change was possible within the framework of capitalist development, while others still believed that political reforms were capable of promoting self-sustaining growth.

One of the main mechanisms that led to the development and persistence of underdevelopment is unequal exchange in international trade (Birkan 2015). The theory of unequal exchange expounded by Raul Prebisch, Arighi Emmanuel, and Samir Amin sought to clarify Marx’s law of value through differential wage costs. The Prebisch-Singer thesis argued that there is a secular tendency for the price of primary commodities to fall relative to manufactured commodities due to different income elasticities of demand. In other words, technical progress, which increases incomes in the developed nations, leads to lower demand and consequently lower prices for primary commodities in the underdeveloped nations (Birkan 2015). Therefore, if you are stuck producing cotton or silver, the purchasing power of your imports will fall, and your ability to invest, grow, and develop will remain implausible.

In following the Ricardian theory of value, dependency theorists maintained that foreign trade simply mediates the exchange of use-values, while the magnitude of profit and value remains unaltered. This hypothesis starts with the assumption that there is an international equalization in the rate of profit and an immobility of labor power. The underlying logic of this reproduction scheme is that commodities exchange at value; that is, that their prices coincide with their values (Grossman 1929). This notion is only possible if we abstract from competition and assume that all that happens in international trade is that a commodity of a given value exchanges for another at the same value. But in reality prices of production deviate from their value because of the specific kind of labor that creates value: abstract or indirect social labor.

In contrast, Marx draws out the role of competition in international trade, in particular, the labor-time socially required for production (Grossman 1929). For Marx, the magnitude of socially necessary labor-time differs from country to country on the basis of competition among capitalists to introduce new methods of production, wherein the capitalist who sells goods below their social value appropriates to surplus labor a greater portion of the working day. Hence, there is a constant tendency in capitalism to increase the productivity of labor, in order to cheapen commodities, and by such cheapening to cheapen labor itself (Marx 2011). Thereby, the commodities of advanced countries with a higher organic composition of capital will be sold at prices of production higher than their value, while those of the underdeveloped countries, at prices of production lower than their value.

Therefore, Marx argued the price of any given commodity generally deviates from its value, because abstract labor is measured by a social average that is always fluctuating, especially because of technological innovations (Hudis 2012). To Marx, the technologically advanced countries make a surplus profit at the expense of technologically less-advanced countries. In other words, unequal exchange is not a question of differential wage costs but of additional surplus value, which is obtained through competition on the world market through non-equivalent magnitudes of socially necessary labor-time. In Chapter 20 of Theories of Surplus Value, entitled “Disintegration of the Ricardian School,” Marx writes,

Three days of labor of one country can be exchanged against one of another country. … Here the law of value undergoes essential modification. … The relationship between labor days of different countries may be similar to that existing between skilled, complex labor and unskilled, simple labor within a country. In this case, the richer country exploits the poorer one, even where the latter gains by the exchange.

Here, Marx highlights the international effects of the law of value, in particular, the unequal determinations of labor-time which he modified into a social average in Capital Vol. 1. Similarly, in Notebook VII in the Grundrisse, entitled “The Chapter on Capital / Bastiat and Carey,” Marx states,

From the possibility that profit may be less than surplus value, hence that capital [may] exchange profitably without realizing itself in the strict sense, it follows that not only individual capitalists, but also nations may continually exchange with one another, may even continually repeat the exchange on an ever-expanding scale, without for that reason necessarily gaining in equal degrees. One of the nations may continually appropriate for itself a part of the surplus labor of the other, giving back nothing for it in the exchange, except that the measure here [is] not as in the exchange between capitalist and worker.

Furthermore, in Capital Vol. III, Marx writes,

Capitals invested in foreign trade can yield a higher rate of profit, because, in the first place, there is competition with commodities produced in other countries with inferior production facilities, so that the more advanced country sells its goods above their value even though cheaper than the competing countries. In so far as the labor of the more advanced country is here realized as labor of a higher specific weight, the rate of profit rises, because labor which has not been paid as being of a higher quality, is sold as such. … As regards capitals invested in colonies, etc., on the other hand, they may yield higher rates of profit for the simple reason that the rate of profit there is higher due to backward development, and likewise the exploitation of labor, because of the use of slaves, coolies, etc.

In the examples cited above, Marx emphasizes the colossal importance of foreign trade as a means for advanced countries to exploit less-advanced countries. One of the many simplifying assumptions that underline dependency theory and theories of the “new imperialism” is that Marx only examined the phenomenon of an isolated capitalism or national capitalism. Yet Marx himself consistently highlighted that capitalism is a world-polarizing and ever-expanding system (For detailed evidence see Pradella 2012 and Anderson 2010). In 1859, Marx proposed a six-book structure for his examination of the development of capitalism and intended that one of the six be devoted to the world market. At the same time, within his activity in the First International he declared the necessity of building unity between class struggles in imperialist countries and anti-colonial resistance in colonized countries and dependent countries (Anderson 2010, Pradella 2012).

It should also be noted that dependency theory focused exclusively on the quantitative side of value—that is, the amount of labor-time embodied in a commodity—as opposed to the qualitative side, on the kind of labor that creates value. In other words, those theorists contended the value of any commodity is purely and solely determined by the quantity of labor required for production. Marx, on the contrary, argues that living labor forms the substance of value only when it takes a specific form—indirect social labor or alienated labor (Hudis 2012). Thus, dependency theorists never investigated the social relations that create exchange value, which made them reduce socialism to overcoming relations of exchange as opposed to ending abstract value production. In the next section I will explore the ramifications of reducing the law of value simply to a quantitative relationship.

II.

From the beginning, nearly all dependency theorists argued that industrialization was the key ingredient of economic development—the idea that a transition from the production of primary commodities to finished commodities signaled the beginning of development, what came to be coined “import substitution industrialization.” There was, however, a sharp division among dependency theorists on the strategic objectives of industrialization. For the bourgeois nationalist and social democratic school, industrialization was simply a means to construct autonomous capitalist development by removing obstacles deriving from unequal exchange, while for the revolutionary socialist school, industrialization was a means to overcome the unequal hierarchy of exchange and the transition to socialism.

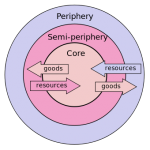

This division culminated in the formulation of two divergent descriptive theses: (1) “associated dependent development,” (2) “development of underdevelopment.” The followers of “associated dependent development” maintained that some peripheral states have historically experienced economic development, which involves some degree of industrialization combined with an alliance between international and local capital (Cardoso and Faletto 1978, Evans 1979). This is not a phase all peripheral states will be able to reach, as it implies a very distinct position within the international division of labor, namely, that they form what Immanuel Wallerstein calls the “semi-periphery.” On the other hand, the followers of “development of underdevelopment” maintained that peripheral economies are incapable of recapitulating the developmental trajectory of the core. Nevertheless, what they all held in common was the notion that the periphery must “delink” from the exploitative conditions of the capitalist world economy.

The concept of delinking can be understood as a strategy of autonomous development or a fundamental withdrawal from capitalist relations of exchange. The original form of delinking was similar to mercantilism, a strategy for states in the early stages of industrialization to close off external relations with the core to protect infant industries (Pieterse 1994). This model was essentially delinking for the sake of relinking, re-entering the world market once industries reach a sufficient level of development. The second form of delinking was disassociation from capitalism as part of the transition to socialism (Amin 1985, 1990; Frank 2005; Pieterse 1994). This strategy of disassociation and “socialism in one country” was formulated to suppress domination from the core by implementing national reconstruction in the periphery. The secondary strategy of this program was weakening the capitalist world economy: It was thought that if enough peripheral states delink, capitalism will decline, resulting in a structural crisis reducing growth in the core.

Like Ricardo, the followers of dependency theory reduced the logic of capital to market phenomena without grasping social relations at the point of production. As a result, dependency theory is concerned with how products come into being (commodities, capital, and money) and how their value is unequally distributed. The product (capital) is the unit of analysis, not the human subjects that create and shape it. Since exchange value is inseparable from value it cannot transcend the very essence of capitalism: abstract labor, production for the sake of value. For Marx, capitalism exists wherever the principle of social organization is the reduction of human labor to abstract forms of value-creating labor. Marx argues the exchange of things is not merely a quantitative relationship since there must be a commonality that enables them to be exchanged. And the common element of relations of exchange is abstract labor.

Thereby, the strategy of delinking inverts the order of things; more specifically, it constitutes a limited standard for transcending capitalism that brings us right back into the jaws of capital. This is because delinking is presupposed by the idea that the source of capitalism’s contradictions lies not in its abstract value creating form but, rather, in its unequal form of distribution. Hence, socially necessary labor-time continues to operate but now in a national or regional context. The individual capitalist or bureaucracy of the state continues to be driven by the incessant need to extract the maximum amount of surplus value from labor, as was reflected by the state-capitalist experiments in the Soviet Union and Eastern Europe. But now delinked capitalist enterprises are cut off from access to the social average of their competitors, which leads to inferior methods of production.

As long as capitalism has not been totally uprooted by human subjective activity, its basic laws of motion persist via the law of value and surplus value (Dunayevskaya 2003). This means both the exploitation and reification of labor by the despotic plan of capital. As Raya Dunayevskaya argues in Philosophy and Revolution,

The Marxist truth, the plain truth, is that just as economic reality is not mere statistics, but is the base of existence, and just as the greatest productive force is not the machine, but the human being, so the human being is not only muscle, but also brain, not only energy but emotion, passion and force—in a word, the whole human being. This, just this, was of course Marx’s greatest contribution to “economics,” or more precisely, to revolutionizing economics, to unearthing the whole human dimension.

When the masses are denied their self-activity, there is no way to avoid being subsumed into the barbarous whims of the world market dominated by advanced technologies. This was the case for the newly independent nations across Africa and Asia trapped in their monocultural past as the price of their one crop was determined by the price structure of the world market. Whether or not they negated private property or imposed a state plan had little effect on the neocolonial structure (Dunayevskaya 2003, 225). Even a state like Cuba, where state planning is basically universal, the price of sugar is still determined by socially necessary labor-time established by world production. Moreover, the level of technological development and accumulated capital become the main determinants of unequal exchange when the masses are not allowed their self-activity. As Marx shows us, the law of value can only be eliminated when freely associated labor takes its destiny into its own hands; only freely associated labor can strip the fetishism from commodities.

But what perhaps put the final nail in the coffin of dependency theory was its failure to anticipate the emergent “new industrial division of labor” in the world economy. For example, the rapid export-oriented industrial development of the “East Asian Tigers” in the 1970s presents major problems for Andre Gunder Frank’s thesis of the “development of underdevelopment.” Not only are nations like South Korea and Taiwan producing consumer durables (cars, phones, tablets, TVs, and so on) for profit, but also exporting capital to other parts of Asia and Europe. By contrast, in places like Brazil and India, foreign multinationals of the North flourish alongside local bourgeois industrial development. According to John Smith, author of Imperialism in the 21st Century (2015), the globalization of the production process is the most unique and transformative feature of so-called neoliberal globalization. Smith argues the relocation of production takes two main forms: foreign direct investment, when outsourcing is shifted to the periphery but “kept in-house,” and “arm’s length outsourcing,” when firms outsource production to an independent subcontractor (such as Foxconn or Pegatron), yet maintain control of the process of production and continue to capture the benefits of output (Smith 2015).

Despite some of the analytical weaknesses of John Smith’s understanding of modern imperialism (which I briefly discuss below), he is quite right to underline the distinctiveness of the globalization of the production process. Smith shows that the world’s “economically active population” grew from 1.9 billion in 1980 to 3.1 billion in 2006, a 63 percent increase. The so-called “emerging nations” now account for 84 percent of the global labor force, of which 1.6 billion perform wage labor and 1 billion are small farmers and workers of the “informal economy” (Smith 2015). However, Smith sees the foundation of modern imperialism as the super-exploitation of wage workers in the South (the periphery) through driving wages below the value of labor power. Smith’s case for super-exploitation theory depends on the premise that capitalists seek to increase profits by the replacement of high-wage workers in imperialist countries with low-wage workers in the global South—so-called “global labor arbitrage” (Smith 2015). One of the conclusions that Smith draws is the error of portraying the workers of developed nations as a “labor aristocracy” basically living off the surplus value produced by workers in underdeveloped nations.

In many ways, Smith’s analysis of imperialism is consistent with dependency theory’s argument that imperialist countries are developed only because of their exploitation of the underdeveloped nations. As Michael Roberts has recently argued, the higher wages and social benefits of workers in developed nations may indirectly derive from the super-profits of multinational corporations they work for—but that is the result of the class struggle over the share of value going to wages, not directly as a result of imperialist exploitation (Roberts 2016). It is incorrect to maintain that super-exploitation operates internationally, simply because wage levels are lower in underdeveloped nations relative to developed nations. What determines exploitation in Marxist terms is the ratio between surplus value or profits and the value of labor power or wages (Roberts 2016). Therefore, what matters is whether the wages of workers in developed nations exceed the value they create. I am not at all suggesting that super-exploitation does not exist, but rather expressing my doubts as to the extent that it operates as the basis of modern imperialism.

As I have already shown, the lens through which to view imperialism is that of Marx’s law of value. It is the race for higher rates of profit that is the real driving force of world capitalism. Historically, imperialism has served as a major counteracting factor to the tendency for the rate of profit to fall. For example, beginning in the 1980s and onwards, the rate of profit in major capitalist economies began to decline, resulting in a renewal of capital flows into underdeveloped nations. This significant increase in capitalist investment brought a massive supply of peasant and non-capitalist labor into the capitalist mode of production for the first time and sometimes at a cost below the value of labor power in developed countries, that is, super-exploitation (Carchedi and Roberts 2013). However, several Marxist analyses of the world rate of profit suggest efforts to relocate production to the South coupled with neoliberal policies on wages, public services, and trade unions in the North have failed to fully restore the rate of profitability. There is still a long way to go for the world rate of profit to be driven up, and it will likely take the further destruction of wealth and value.

The failure of dependency theory to creatively reconstitute Marx’s law of value in light of new problems presented by the imperialist evolution of world capitalism resulted in its overall decline as a school of thought. Of the founders of dependency theory, one, Fernando Henrique Cardoso, became a neoliberal Brazilian president (succeeded in 2002 by Luis Inácio da Silva), implementing policies that he would have surely denounced as ultra-reactionary during his Good Old Days as a “dependentista.” Samir Amin remains a self-declared Maoist who maintains that China has been following an original path of development since 1950 that is neither capitalist nor socialist. On the other hand, Andre Gunder Frank eventually began arguing that capitalism and socialism are ideological inventions that have never existed. Nonetheless, the debates sparked by dependency theory in the 1960s and 1970s remain an important reference point for individuals attempting to understand the theories of imperialism and exploitation.

In some respects, today’s situation has not changed much, as many on the left—including both anarchists and Marxists—continue to assume that a socialist society consists of simply overcoming the market and private property. More promising are the new global justice movements that have largely rejected the concept of a vanguard party, the seizure of existing state power, and the bureaucratic state planning of the former so-called socialist countries. However, there appears to be little or no consensus on how these decentralized and anti-authoritarian movements can break with the law of value. Marx’s critique of Proudhon, the neo-Ricardian socialists, and later the followers of Ferdinand Lassalle demands that we re-examine abstract value production—the very heart of capitalism—responsible for the production of value, surplus value, and capital accumulation. Today’s generation of revolutionary activists will have to choose its future: We can build freely associated human relations that negate the law of value, or we can repeat the old illusions of past “socialist experiments.” The choice is ours!

Bibliography

Amin, Samir. 1990. Delinking: Towards a Polycentric World. London: Zed Books.

Anderson, Kevin. 2010. Marx at the Margins: On Nationalism, Ethnicity, and Non-Western Societies. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Birkan, Ayşe Özden. 2015. A Brief Overview of the Theory of Unequal Exchange and Its Critiques. International Journal of Humanities and Social Science, 2015.

Carchedi, Guglielmo and Michael Roberts. 2013. “The long roots of the present crisis: Keynesians, Austerians and Marx’s law.” World Review of Political Economy 4,1:86-115.

Cardoso, Fernando Henrique and Enzo Faletto. 1979. Dependency and Development in Latin America. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Dunayevskaya, Raya. 2003. Philosophy and Revolution: From Hegel to Sartre and from Marx to Mao. New York: Lexington Books.

Evans, Peter B. 1979. Dependent Development: The Alliance of Multinational, State, and Local Capital in Brazil. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Frank, Andre Gunder. 2005. World System Development and Underdevelopment. rrojasdatabank.info/.

Grossman, Henryk. The Law of Accumulation and Breakdown of the Capitalist System, Being Also a Theory of Crises. www.marxists.org/archive/grossman/1929/breakdown/.

Hudis, Peter. 2012. Marx’s Concept of the Alternative to Capitalism. Leiden: Brill.

Marx, Karl. 2011. Capital: A Critique of Political Economy, Vol. 1. Mineola, NY: Dover Publications.

Marx, Karl. 2006. Capital: A Critique of Political Economy, Vol.3. London: Penguin.

Marx, Karl. 1973. Grundrisse. Penguin Books in association with New Left Review. www.marxists.org/archive/marx/works/1857/grundrisse/index.htm.

Marx, Karl. 1971. Theories of Surplus-Value. Progress Publishers. www.marxists.org/archive/marx/works/1863/theories-surplus-value/index.htm.

Pieterse, Jan Nederveen. 1994. Delinking or Globalisation. Economic and Political Weekly.

Pradella, Lucia. 2012. Imperialism and Capitalist Development in Marx’s Capital. Leiden: Brill.

Roberts, Michael. 2016. “Modern Imperialism and the Working Class.” thenextrecession.wordpress.com/2016/06/29/modern-imperialism-and-the-working-class/.

Smith, John. 2016. Imperialism in the Twenty-first Century: Globalization, Super-Exploitation, and Capitalism’s Final Crisis. New York: Monthly Review.

Leave a Reply