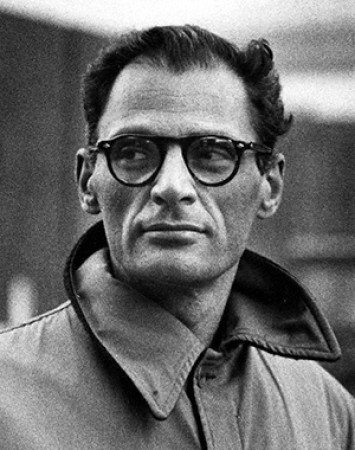

Seventy-two years after his initial Broadway success with All My Sons and 14 years after his death, Arthur Miller continues to cast a long shadow over theater in the United States. His plays are staples of high school drama clubs, college and university theater departments and regional theaters around the country, and his best-known works – Death of a Salesman, The Crucible, All My Sons, A View From the Bridge and After the Fall – have been revived many times on Broadway.

Seventy-two years after his initial Broadway success with All My Sons and 14 years after his death, Arthur Miller continues to cast a long shadow over theater in the United States. His plays are staples of high school drama clubs, college and university theater departments and regional theaters around the country, and his best-known works – Death of a Salesman, The Crucible, All My Sons, A View From the Bridge and After the Fall – have been revived many times on Broadway.

Miller’s influence also extends beyond the United States. Death of a Salesman, for example, serves as the backdrop to Iranian director Asghar Farhadi’s acclaimed 2016 film The Salesman. And it has been said, perhaps apocryphally, perhaps not, that The Crucible has played continuously somewhere in the world since its debut performance in 1953.

Hardly a New York theater season goes by without the revival of one of Miller’s plays. Just last year, the prestigious Brooklyn Academy of Music featured a revival of Salesman while the Roundabout Theatre staged a three-month production of his 1968 drama The Price. Among many attributes, the Roundabout production featured a stellar cast with Mark Ruffalo, Tony Shaloub, Jessica Hecht and Danny Devito as the play’s four characters. While not as well-known as any number of Miller’s works, The Price has been revived on Broadway more times – four – than all of his plays except The Crucible, which has also had four revivals over a significantly longer period of time.

The Price

Like much of Miller’s work, The Price is mostly heavy going. As with Salesman and All My Sons in particular, its main theme is in some ways the lie of the American Dream. Also like those two, the primary conflict unfolds within a family, in this case between Victor Franz (Ruffalo) and his wife Esther (Hecht) and all the more between Victor and his brother Walter (Shaloub).

The specter of the Great Depression hovers over The Price throughout even as the action unfolds three decades later. This, too, is territory Miller has plumbed many times. For Miller, the Depression of the 1930s was only the most extreme expression of the dashing of misplaced hopes for the good life. Its casualty rate was higher and the destruction greater than other low points, but the tragedy of a society in which carving out a comfortable place for oneself through accumulating wealth is the end-all and be-all is the same in 1931, 1968 or 2018. There are always far more losers than winners, for one; and even winners who achieve what we might call upper middle class-dom lose a great deal including much that can never be re-gotten. Always tenuous, wealth obtained in a society premised on swindling somebody else can vanish very quickly. And as we see in The Price in the character of Walter, the psychological and personal costs are often enormous as well.

The 1930s

Miller was 14 when the stock market crashed in 1929 and the formative years of his life were those of breadlines, Hoovervilles and the rumblings of fascism and world war. Those years also marked widespread interest in revolutionary change including in the arts and Miller, who from the time he was a young man was of the Left, was blown away in particular by the early plays of Clifford Odets. Nonetheless, he mostly eschewed the socialist realism, proletarian literature and agit-prop genres that were popular in the 1930s.

Instead, Miller wrote plays one step removed from the battlefield of class struggle. There are no final scenes in his dramas of workers defiantly envisioning coming triumphs with cries of “Strike, strike, strike!” Yet it was he who dramatized the declaration in Awake and Sing by the old Marxist Jacob that “life shouldn’t be printed on dollar bills” better than anyone, Odets included.

Miller’s Influences

Miller’s primary influences go back to earlier traditions including Ibsen, whose An Enemy of the People he adapted on Broadway in 1950. Miller’s staging of Enemy was an indictment of the Red Scare and it featured in its cast the left-wing husband and wife team Frederic March and Florence Eldridge as well as the Communist and soon-to-be blacklisted Morris Carnovsky.

As in a number of Miller’s other plays, The Price includes Thomas Hardy-esque moments of coincidence or misunderstanding that sharply alter the course of events: a missed phone call, a misinterpreted bit of conversation. A good portion of the play is a sometimes harsh back and forth between Victor and Esther about what might have been. When Victor’s brother Walter arrives, the great depth of that might have been and why it never was is revealed.

The Price shares with Salesman and All My Sons the tensions that arise from living by illusions. As he did so expertly so often, perhaps especially in All My Sons, Miller blends the impact of big outside forces with the tensions that exist within every individual and family. That we don’t always know which ends where is one of the things that make his plays, The Price included, so powerful. For Victor, the destructive impact of the 1929 Crash cuts two ways: it ruined his future while also allowing him to keep at bay nagging thoughts that he, too, had some part in the unsatisfied life he has lived. The arrival of his brother midway upsets the structured explanation he has been telling himself for years, as he learns of heretofore unknown familial betrayal.

While we ache for both Loman in Salesman and Keller in Sons, we simultaneously look down on them to a degree for the illusions they harbor. In The Price, our sympathies for Victor are less mitigated. So it is with Esther, too, whose finest moment comes when she rallies to Victor’s side at the end after laying out his many mistakes for much of the play. All of the tensions and hard feelings are accentuated by Miller’s situating the entire play in the confined setting of an attic in an old Manhattan residence. Even with an intermission, the single locale serves to heighten a feeling of claustrophobia throughout as the brothers in particular bear down on each other.

As The Price approaches its conclusion, anyone seeing or reading it for the first time (or the second or third for that matter) is likely to anticipate a possibly amicable resolution. There are several points where it seems the brothers may acknowledge the pain each has caused the other, shake hands and go forward as best as possible. Such a resolution, however, was largely alien to the world Miller strove to create, certainly the world of his best work, and while the conclusion in The Price is not on the scale of Salesman and Sons, the irreconcilability is final enough.

The Hook

In 1950, eighteen years before he wrote The Price, Miller wrote a screenplay about corruption on the Brooklyn docks and the impact it had on longshore workers titled The Hook. Much has been written about the genesis of The Hook including by Miller himself, and the story behind it is undoubtedly familiar to many readers. Writing in 2015, James Dacre, who was instrumental in staging The Hook in England that year to mark the centennial of Miller’s birth, said that the backstory “deserves a screenplay of its own.”

At the time Miller wrote The Hook, he was still very close with Elia Kazan and the two submitted the story to Columbia Pictures’ head honcho Harry Cohn. Miller had had two smash hits on Broadway by then and Kazan, with several recent Hollywood successes and the original staging of Tennessee Williams’ smash hit A Streetcar Named Desire to his credit, had agreed to direct. Cohn initially approved the project but soon insisted that Miller change the story so that the corrupt union leaders be clearly identified as Communists. Miller refused and the project was dropped. Within a few years, Kazan named names before HUAC, signed a lucrative contract with Columbia and went on to direct and win numerous awards for another drama set among longshore workers, On The Waterfront. Miller, meanwhile, told HUAC where to get off, had his passport revoked and kept working as best he could while contending with American Legion pickets at productions of his plays.

For 65 years, The Hook was stashed away where it was read primarily by scholars doing Miller-related research. Then in 2015, Dacre and the Royal & Derngate Theater adapted it for the stage in several major venues in England where it received international attention, garnered rave reviews and was subsequently broadcast as a radio play by the BBC. Despite the success across the Atlantic, there has yet to be a staging in the United States.

Pete Panto

While living in Brooklyn Heights in the 1940s, Miller would walk south along Columbia Street into Red Hook through what was then a thriving commercial waterfront. There he saw graffiti, usually in Sicilian, about a dockworker named Pete Panto: Dov e Panto? (Where is Panto?). An old-time Sicilian dockworker who was a contemporary of Panto’s and my landlord when I moved to that neighborhood in the early 1980s remembered additional graffiti that asked Che ha ucciso Panto? (Who Killed Panto?).

Panto was a member of the International Longshoremen’s Association (ILA) and either a member or close ally of the Communist Party. In the late 1930s, he was organizing fellow workers around democratizing the ILA, doing away with corrupt practices such as the shape-up, and driving the racketeers out of the union. As many as 1,500 dockworkers attended open-air meetings organized by the Brooklyn Rank and File Committee, the group Panto helped form. One evening in 1939, Panto left his home in Brooklyn and disappeared. His body was found two years later in a New Jersey lime pit.

Albert Anastasia and others associated with Murder, Inc. were implicated but no one was ever charged with killing Panto. A hit man named Abe Reles who had turned government witness and helped convict several racketeers, was apparently ready to finger Murder, Inc., but he went out a sixth floor window before he could do so, likely the victim of a hit ordered by Anastasia.

The mostly Italian-American dockworkers carried on bravely despite an atmosphere of intense intimidation that would fester for decades. They formed the Pete Panto Educational Circle (Il Circolo Educativo Pete Panto) to carry forward Panto’s legacy and associates of his kept the Brooklyn Rank and File Committee together as best they could. Their meetings were regularly broken up by goons, however, and within a few years organized rank and file activity had essentially ground to a halt.

A Play for The Screen

The Hook does not attempt to directly tell Panto’s story but it grounds itself firmly in the rough, unforgiving, often violent world of the Brooklyn waterfront of that time. Like so much of Miller’s work, The Hook is a world inhabited primarily by men. The Price, Salesman, Sons, and A View From the Bridge are all centered to a great extent around conflicts between fathers and sons, brother and brother and sometimes both. Even the extended and often riveting back and forth between Victor and his wife Esther in The Price feels like prelude to the struggle between Victor and his brother.

The relationships between Marty Ferrara, the main character, and the men in his world are central enough in The Hook just as in those other plays but there are also differences. There are no father-son or brother-brother tensions, for example, and Marty’s wife Therese is central to the drama within the Ferrara home to a degree greater than in Miller’s plays. Their relationship is rendered with great depth and reminiscent among other of his plays only of the love that blossoms between Chris and Ann in All My Sons. Their relationship grounds Marty, prompting him to do the right thing at several crucial junctures, and is one of the most effective and moving parts of the story.

Much of the explanation for what makes The Hook different from other Miller works lies in the fact that it was written for the screen. There is a greater breadth of locales than is typical of Miller including scenes at work, on the streets and in the union hall, as well as any number in the many kinds of random spots that fill working class neighborhoods.

Miller seems to have been drawn to film because he regarded it as better-suited to stories that might include more action, faster pacing, outdoor locations and other devices more conducive to the kind of story he wanted to tell. Perhaps that is why he apparently never attempted to re-work The Hook for the stage. Perhaps, too, he knew that it would be virtually impossible in the 1950s to obtain financial backing for a play in which the villain is the profit system. Five years later, when Miller again dramatized Brooklyn Italian-American dockworkers in A View From the Bridge, he wrote a very different kind of story. In contrast to The Hook, most all of Viewtakes place in one location – the Carbone home – and workplace and union concerns are peripheral.

Miller’s Audience Today

It’s anybody’s guess what those who go to these many Miller revivals take away from his plays all these years later. With its obscene prices, Broadway skews toward the better-heeled and it’s easy (and true enough) to interpret any number of Miller’s plays, The Price included, as primarily about unfulfilled lives resulting from missed or stolen opportunities. But one of the great strengths of Broadway, the cost of tickets notwithstanding, is that it still provides a place where artists like Miller can lay bare the darkness at the heart of the profit system. The destruction of illusions can be a harrowing experience and one exits The Price, much as I recall exiting the 1984 Dustin Hoffman revival of Salesmen, as needing some time to recover. Yet the right questions are there and in the story one can uncover much more than troubled family members tearing at each other, a theme that is a great strength but also often a limitation in the work of both Eugene O’Neill and Miller’s great contemporary Tennessee Williams.

Even if those who can afford $150 a pop are not among those tottering on the brink of economic collapse, the parallels between the devastation Miller wrote about with such insight and the inescapable sense today of looming catastrophe is unmistakable. Whatever one can get from any number of modern dramas available every night on HBO and Showtime, one suspects that people return to Miller revivals and similar dramas of theater because there are few places where they can get such an unvarnished look at the modern world. That New Yorkers were able to see a splendid adaptation of The Hairy Ape, O’Neill’s most class-conscious play at the same time they were able to see The Price, is further indication that something unsettling is in the air.

Miller would likely be delighted The Price ran at the same time as Sweat, a new masterwork by Lynn Nottage that touches on important themes of economic collapse and which earned her a second Pulitzer Prize for Drama. Miller knew all too well of Broadway backers’ preference for the tried and true and the already familiar and famous, which today often means him. We can only imagine the number of plays like Sweat that have been pushed aside in favor of yet another revival, classics marketed as speaking to a specific time that has come and gone. Try as some undoubtedly have, pigeonholing Miller’s work in that is virtually impossible. As much as anything being done today creatively, the best of his plays speak directly to the wreckage of a society in freefall.

What Next?

Going forward, perhaps someone will bankroll an American production of The Hook. That it was well-received in England and provides a fresh Miller work to stage provides hope. Pending that, revivals of a few of Miller’s excellent but somewhat overlooked plays are in order. A Memory of Two Mondays, first staged on Broadway in 1955 and not seen in New York since 1976, would be a terrific choice. Another of his plays where the aftermath of the 1929 Crash is front and center, A Memory of Two Mondays, shares with The Hook a focus on the workplace. Full of people stuck in jobs that barely pay the rent and that they hate but are afraid to leave, Memory is as good a story for the era of Trump as anything around today. It’s a short play, however, and thus would likely have to be paired with another work. Imagine if some enterprising soul got the bright idea to pair A Memory of Two Mondays with Odets’ Waiting for Lefty, which, incredibly, has not been seen on Broadway since its initial production in 1935.

Even better would be a revival of Miller’s wonderful full-length play The American Clock, another Depression-era tale that ran unsuccessfully for a mere three weeks in its 1980 Broadway debut. The American Clock could serve as a nice departure from the Miller people know best, with its many laughs and songs that greatly enhance the tragedies and the solidarity at the core of the story. A new staging would hopefully be based on the original and without the changes Miller was pressured to make, changes that seriously weakened the play. The original version has played successfully around the world as well as in an all too brief revival Off-Broadway in 1997 and is long overdue to be presented on Broadway as Miller intended.

Broadway notwithstanding, regional theaters and high school and college theater departments will likely remain the primary homes for Miller productions. There’s no reason to believe that will change any time soon. And as long as the Trump crowd, Rachel Maddow and the Washington Post smear anyone who challenges the myth that is the United States, The Crucible anyway is likely to remain a big favorite for years to come.

Thanks to William Mello and Jane LaTour for their assistance in securing a copy of The Hook.

Andy Piascik is an award-winning author whose most recent book is the novel In Motion.

He can be reached at andypiascik@yahoo.com.

Seventy-two years after his initial Broadway success with All My Sons and 14 years after his death, Arthur Miller continues to cast a long shadow over theater in the United States. His plays are staples of high school drama clubs, college and university theater departments and regional theaters around the country, and his best-known works – Death of a Salesman, The Crucible, All My Sons, A View From the Bridge and After the Fall – have been revived many times on Broadway.

Seventy-two years after his initial Broadway success with All My Sons and 14 years after his death, Arthur Miller continues to cast a long shadow over theater in the United States. His plays are staples of high school drama clubs, college and university theater departments and regional theaters around the country, and his best-known works – Death of a Salesman, The Crucible, All My Sons, A View From the Bridge and After the Fall – have been revived many times on Broadway.

Leave a Reply