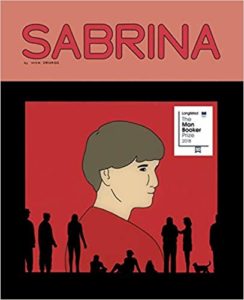

Sabrina, a graphic novel by Nick Drnaso, is the first graphic novel to be long listed for the Man Booker Prize in the award’s long history. It came as a surprise to many of the loyalists of the literary community (those who were also surprised by Bob Dylan’s Nobel Prize nomination) and opened up questions about authenticity of form and the role of literary jury.

Sabrina, a graphic novel by Nick Drnaso, is the first graphic novel to be long listed for the Man Booker Prize in the award’s long history. It came as a surprise to many of the loyalists of the literary community (those who were also surprised by Bob Dylan’s Nobel Prize nomination) and opened up questions about authenticity of form and the role of literary jury.

Among debating threads of opinions, the rising significance of graphic novel as a form stands un-refuted. They have become important and effective classroom pedagogical tools, an important intersection between visual and textual storytelling practices, and a marker of the epochs in which they are written, like modern nihilism and dreariness in Drnaso’s Sabrina.

The aim is to look closely at the function of the graphic novel as a marker of the political life of a region, while the narrative is “innocently” focusing on the personal coming-of-age story. The graphic novels Persepolis and Munnu are apt examples; they engender a powerful moment (that continue to be) in the political realities of Iran and Kashmir, respectively. These texts will serve as entry points into the discussion that encompasses the form, the theme of political existing in the personal experience, and the use of comedy to speak of state-sponsored oppressive regime.

Political History of the Form

“More than ever, graphic novels are the vehicle of choice for people who wish to present an alternate version of past, present, and future—to give voice to the minority, the abused, the unrecognized, the maligned, and the forgotten,” notes a recent Nuvo article by James Dolan. Images that present, represent, and satirize political events have been around since the time of Leonardo da Vinci. William Hogarth is hailed as the pioneer of this form that accommodated social criticism of the status quo. In a manner, then, graphic novels have come out of this lineage of political expression through images. They might not be linear successors of political comic strips, but they definitely carry the advantages of having a viewership that is familiar with this history of images.

Caricatures and allusion are two of the most popular tools used by creators of political images to comment on the status quo. In this study, it might be significant to take a look at Joseph Keppler’s magazine Puck, that used humorous and witty cartoons to comment on the day’s happenings-by ridiculing prominent governmental figures, and, thus, giving voice to the larger sentiment of the masses. The popularity of the magazine was another testament to mixing of mass media, cultural motifs and favoring sources that bravely spoke for the American public.

Therefore, the form also has a long history of being able to tackle grave matters with a lighter treatment, while not losing any of the gravitas. Masters of political imagery are relatable, accessible, and important sources of political education for the masses. The form achieves what academic books on political subjects often cannot: the reach and influence. Graphic novels carry the history of having been confused with superhero comics (which, recent scholarship claims, are not apolitical) and the potential for serious political commentary. The article by Dolan emphasizes the role of graphic novels to go against propaganda and create “an interplay between medium and message.” This article will look at two novels that have exercised these tools of lightness, while accommodating representation of respective political realities in the personal storytelling.

As the canonical understanding of history as a monolith is slowly eroding, there is more space to accommodate a cohesive picture of history by gathering perspectives of multiple stakeholders of a historical event. Subjective accounts of events like war and political regimes, similarly, help us create a complete picture of our histories. As with the ethical concerns around social research, the question of “authenticity and validity” of perspectives does rise with memoirs. Graphic novels are no exception to these and it would be up to the user of memoirs as pedagogical tools and upcoming scholars to explore these ethical conundrums.

A Girl Comes of Age In and Out of a HeadScarf: Marji in Persepolis

“As an Iranian who has lived more than half of my life in Iran, I know that this image (of fundamentalism, fanaticism, and terrorism) is far from the truth. This is why writing Persepolis was so important to me, writes Marjane Satrapi in the introduction to her autobiographical graphic novel Persepolis. Persepolis, since then, has been hailed as an act of launching into a particular historical time (the years surrounding the Iranian Revolution) from panels and stories from her own life. The novel begins as the Shah regime (pro-Western forces) is being opposed by a popular mass retaliation for anger against sharp economic downturn and monarchical rule, which was seen to be established by the Western powers. The revolution that overturns this monarchy also leads to a period of radicalization of politics, education, and social structures of Iran. The Iran-Iraq war also ensued for years and the political and social landscape of the country is irretrievably changed, as with any major shifts in ideological and cultural revolutions. Further, around the early 2000s (the time of Persepolis’ publishing), Iran was seeing political turbulence in terms of severe political shifts in the Middle East. These can be seen as a legacy of the incidents mentioned in Persepolis.

Marji, the protagonist, asks many questions, reads a lot, is not the most obedient child and has been brought up to have her own opinions. The first volume of Persepolis follows the journey of young Marji as she comes to terms with very personal implications of what is going on in her country. The uniform she wears takes a sharp turn that now includes headscarf and the conversations around morality and gender are religious in nature. She realizes that the rhetoric of war in books are very different from the daily realities of war. In particular, a panel about her conversation with her classmate Pardisse confirms that Marji, who was celebrating the bombing of Kuwait a fortnight earlier, is forced to confront the human losses in war. It makes her question war propaganda when her friend confesses that she would have preferred for her dead fighter pilot father to be alive and jailed (under the then political regime) than have lost life as a valiant, “patriotic martyr.”

Finding one’s identity is an important theme in coming-of-age novels of all kinds. We are invited to take part in Marji’s search for identity through her high school years, jobs, romantic relationships, and trysts with authorities in the second volume of Persepolis. The daily life of a young, smart, and opinionated woman in Iran is portrayed as a series of panels that capture her teenage in Austria, the identity crisis of being a westerner in one’s own country, and finding ways of defying oppressive expectations from women in a radicalized educational and societal setting. These panels also open up spaces where the youth find gaps to exercise their right to leisure and enjoyment, like the parties that both genders partake in. The story ends with her departure for France as a talented artist who needed more possibilities of expression. While Persepolis can be read as a wholesome account of a young lady coming-of-age in the late twentieth century Iran, it would be more fruitful to read the personal account as a layer in the palimpsest of historical and political recording of the time.

A Boy Comes of Age Hopping around Barbed Wires: Munnu in Kashmir

Kashmir has been in international news since August 2019 for political reasons. The revocation of Article 370, in an annexing or empowering move—depending on the source that one reads, grabbed headlines the world over. The supporters of the move call this a historic move by India to empower the valley, which has always been keen to maintain its individualistic territorial identity. The other party disagrees with the empowerment argument as the statistics show that Kashmir is ahead of most parts of India in terms of development indices. They look at this occurrence as India’s aggressive military move to curb dissent and realize the ruling far-right party’s promise of a ‘unified India’. The resonances to the self-determination issue of Kashmir valley dates back to the very years that India was formed as an independent nation after decolonization. In Malik Sajad’s Munnu: A Boy from Kashmir, we meet Munnu, the autobiographical protagonist, as he, a small boy, witnesses the happenings in his hometown in Indian-Administered Kashmir.

The most striking imagery about the book is the depiction of Kashmiris with faces of hangul deers. Hangul is a particular species of stag that is known to be endangered. The metaphor strongly speaks to the sentiments of the “generation of conflict”—a generation of Kashmiris born and brought up around curfews, forced disappearances, intense military presence, and identification parades. This generation of Kashmiris, especially if they were not from affluent backgrounds, had to suffer an erratic educational system too—a fact that is emphasized by Sajad in the novel. The conflict and its tensions occupy center-stage as the life of the little boy unfolds on the pages. From the panels that depict childhood business ventures as wooden AK-47 carving to panels that describe how his identity as a Kashmiri proves dangerous in Delhi, there is a palpable sense of impending doom in the novel.

In an especially mortifying episode, after the burial of a neighbor and militant Mustafa, Munnu is overcome by nightmares where he dreams of several dark motifs and suffocating scenarios. This episode gives us a glimpse into the trauma experienced, and still being experienced, by the generations that grew up in the valley exposed to two countries warring with each other over Kashmir’s resources and land. In this process, the lives and peace of mind of the populace is sacrificed. The strip of novel which depicts Munnu’s search for Jammu and Kashmir’s history can be read in parallel with his search for personhood and subjecthood. As he gains more knowledge of his land’s history, he is ready to equip himself with substantiated opinions as a Kashmiri and as an illustrator. Munnu is a coming-of-age story that highlights the experience of an individual residing and acquiring identity in a conflict-torn area. In this process, his individuality is pushed to the background while the state-subscribed political identity as a Kashmiri, or Muslim, or dissenter or “the other” is foregrounded.

A Parallel between Comedy and Graphic Novel as Tools of Speaking Experience: The Personal is Always Political

In a review of Munnu by Rohit Chakraborty, he writes, “The nuanced bildungsroman that is Munnu, the steady metamorphosis of the naive primary schoolchild to the blood-boiling political cartoonist, employed in his adolescence, is some distant cousin of Marjane Satrapi’s Marji in Persepolis.” It is not a coincidence that these two graphic novels, along with some genre-redefining pioneers like Maus, are spoken of in the same breath. The aforementioned palimpsest of personal coming-of-age memoir co-existing with the political, social, and ideological turmoil of a conflicted and war-torn area and public imagination is easily available to study. Further, it would be disserving to disregard the political in the fierce personal narratives. It would give the works more credit if one were to look at the personal narrative intertwined with their political realities. One often finds political reasons for personal events in Munnu’s and Marji’s life and personal anecdotes become ways to understand the human ramifications of political shifts.

In conclusion, memoirs that are written in the form of graphic novels, especially the ones that are set against clear political contexts, can serve as tools to study history. Persepolis and Munnu are but examples of how memoirs and graphic novels can carry conversations of gravitas in public imagination, in classrooms, and in campaigns for raising awareness about the life of people in conflict-areas. One can take an ethical stance after regarding whether more children should come-of-age around barbed wires and threats to their survival.

Leave a Reply