One hundred years ago the most democratic revolution in history took place. Led by the Bolshevik Party, the Russian working class, allied with the peasantry and organized into mass democratic institutions—the soviets—took power.

The only precedent for it was the Paris Commune of 1871, in which the working people of Paris seized control of their city but were able to hold onto it for only two-and-a-half months. After the Commune fell, Karl Marx wrote that it “will be forever celebrated as the glorious harbinger of a new society.”

The workers’ democracy created by the Bolshevik Revolution did not survive either, although it took a few years, not months, to bring about its complete demise. For a short time, however, Soviet Russia proved that socialism was a real possibility, not merely a beautiful dream. It offered to the world an inspiring glimpse of the human potential for reorganizing social life according to principles of freedom, dignity, and equality.

Rosa Luxemburg had her criticisms of the Bolsheviks, but she wrote,

It is not a matter of this or that secondary question of tactics, but of the capacity for action of the proletariat, the strength to act, the will to power of socialism as such. In this, Lenin and Trotsky and their friends were the first, those who went ahead as an example to the proletariat of the world: They are still the only ones up to now who can cry with Hutten, “I have dared!”1

The “February” Revolution

By the end of 1916, more than two years into World War I, it was clear that the tsarist autocracy was dragging Russia down to disaster. Russian war casualties were far greater than those of any other country involved. Most of the commanding officers were incompetent. There were serious shortages of weapons and supplies. Transportation was breaking down, and, with the onset of another bitter Russian winter, the cities were running out of food and fuel. Meanwhile, corruption was rampant: Manufacturers made millions selling shoddy goods to the army. The court and the aristocracy indulged themselves to the full; the jewels and ball gowns displayed for the 1916-1917 season were the most lavish and expensive in years. All this was noted with bitterness by the common people. The patriotic mood of 1914 had evaporated, and the tsar, the government, and the nobility were now loathed by almost everyone.

Against the advice of his ministers, the tsar had taken personal command of the army, leaving the capital, Petrograd (the new name for St. Petersburg, which sounded too German), in the hands of the unstable Tsarina Alexandra and her adviser, a bizarre “holy man” named Grigori Rasputin, whose drunken debaucheries and sexual escapades with ladies of the court were by now an open secret. Despite Rasputin’s notoriety, Alexandra would not hear anything against her “Friend,” as she referred to him in letters to her husband. Instead, she believed he had literally been sent by God to guide her and the imperial family.2

All this was too much even for the court, some of whose members decided that the only way to save the autocracy was to get rid of Rasputin. The most common version of Rasputin’s death, though some scholars have disputed it, is that Prince Felix Yussupov, an extremely wealthy young nobleman who was married to a Romanov, arranged with a few others to lure Rasputin one cold December night to a “party” in his palace, where the advisor would be assassinated. While his fellow conspirators waited upstairs, the prince entertained his victim in a basement room. First the guest was fed small cakes, each one of which contained enough poison to kill several men instantly. These had no visible effect. Then Rasputin asked for wine, which had also been laced with poison. To Yussupov’s amazement, Rasputin quaffed the deadly beverage with satisfaction. The prince’s victim then begged him to play the guitar and sing gypsy songs, so for two-and-a-half hours, Yussupov strummed and warbled while waiting for the poison to take effect. Finally, the prince pulled out a revolver and shot the holy man. Rasputin fell, but then moments later jumped to his feet and grabbed Yussupov by the throat. The prince managed to break free and run upstairs, with Rasputin following him on all fours, howling. There he was shot several more times. Fleeing outdoors, he finally collapsed in the snow, where the assassins then clubbed him over and over again. Still breathing, Rasputin was wrapped in a curtain and pushed through a hole in the ice over a nearby river.

The imperial family was devastated by the death of their friend, but the news prompted general rejoicing in the streets of Petrograd. By now, however, nothing could be done to save the Romanovs. And when the time came, the autocracy proved rather easier to kill than Rasputin.

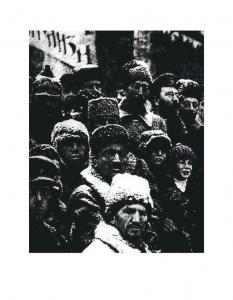

During January and February 1917 deep anger simmered just below the surface in Petrograd and occasionally burst out in protest. There were some strikes. Women waiting in long lines outside bakeries rioted when bread supplies ran out. March 8 was International Women’s Day, a date commemorated by the Socialist International every year. The socialist groups in Petrograd—Mensheviks, Bolsheviks, and Socialist Revolutionaries (SRs)3—planned to pass out leaflets, make speeches, and hold a demonstration or two, nothing more. But things got out of hand. Women textile workers decided to go on strike. Leaving their plants and marching past the bigger factories where the men worked, they yelled “Bread for the Workers,” “Come Out,” and “Stop Work,” and they threw snowballs through the factory windows. The men joined them, and by the next day 400,000 workers were on strike in Petrograd. Now the crowds were yelling “Down with the Autocracy” and “Down with the War.” The “February Revolution” had begun.4

The government responded to the strikes and demonstrations as it had always done—with bullets, sabers, and thick leather whips called knouts. But soon the unthinkable began to occur: Cossacks5 and soldiers refused to fire on the people. Many of them mingled openly with the workers, sometimes helping to kill or disarm the police, who then quickly went into hiding. Red flags were hoisted everywhere. Government officials were put under arrest. When the tsar tried to return from the front, railway workers refused to operate the trains.

The autocracy had been overthrown, but what would replace it? On March 11, some members of the Duma6 created a Russian Provisional—that is, temporary—Government, a cabinet of ministers consisting of twenty of its most prominent members. Most belonged to the Cadets (Constitutional Democrats), the party of middle-class liberalism. Consequently, although the prime minister was a nobleman, Prince Georgi Lvov, and the Provisional Government included one socialist, the SR Alexander Kerensky, the Cadet leader Paul Miliukov was its dominant figure. Miliukov at first hoped to reorganize the government as a constitutional monarchy, but he soon realized the people wanted nothing more to do with tsars. So at the Provisional Government’s behest, Nicholas II, along with his son Alexis, abdicated the throne on March 15 in favor of his brother, the Grand Duke Michael, who in turn abdicated the next day. After 304 years, the Romanov dynasty was no more.

But could the Provisional Government command the support of Russia’s people? The Duma, after all, from which it came, had been elected by an extremely undemocratic voting system; it represented landlords, business owners, and professionals, but not workers and peasants. Moreover, nobody had actually elected Miliukov, Lvov, and the 18 others to be a government, provisional or otherwise; they were really self-appointed. So even though the Provisional Government only claimed the right to rule Russia until such time as the people could elect a Constituent Assembly to draw up a new constitution, its power was shaky from the beginning.

This was true especially because a parallel power had emerged alongside the Provisional Government—the Petrograd Soviet.7 As soon as the revolution began, workers in the factories and soldiers and sailors stationed in the capital started electing 2,500 delegates to a new body, the Petrograd Soviet of Workers’ and Soldiers’ Deputies. It was ultra-democratic, a kind of parliament of the working class, whose members were paid workers’ wages and could be recalled and replaced at any time by those who had elected them. The Petrograd Soviet met in one of the imperial palaces, and later in the auditorium of the Smolny Institute, a former school for aristocratic girls that had been abandoned by its students and faculty after the fall of the tsar. Meetings of the Soviet were a scene of constant debate, noisy and intense; people streamed in and out; reports arrived from different parts of the city or from the battle front; anyone could get up and speak, to the cheers or heckling of the audience. Meanwhile smaller discussions continued in the halls or in the cafeteria over cigarettes and endless glasses of tea (Russians are passionate tea drinkers). The Soviet, not the Provisional Government, was the real center of the revolution.

The February Revolution had been spontaneous—that is, no one had planned or organized it. But as soon as it began, the lead was taken by workers and intellectuals who had long been involved in underground revolutionary work and belonged to the various socialist parties. When elections to the Soviet were held in the factories and military garrisons, it was these men and women who put themselves forward as candidates. When the Petrograd Soviet met for the first time on March 12, it elected an Executive Committee, all of whose members were well-known socialist leaders. The majority of the Executive Committee was held by the Mensheviks, led by Nikolai Chkheidze and Irakli Tseretelli, and the SRs, led by Victor Chernov; the Bolsheviks had only a small minority of committee members. Many of the most prominent socialists, however, were not even in Russia: Vladimir Lenin, the Bolshevik, and Julius Martov, the Menshevik, were still in exile in Switzerland, and Leon Trotsky, who belonged to neither faction, was living in the Bronx when the February Revolution broke out. All, needless to say, were frantic to get back to Russia as soon as possible.

Dual Power

The coexistence of these two centers of authority, which came to be known as dual power, was a constant source of tension and confusion. The Executive Committee of the Petrograd Soviet acted in many ways like a government, and not just of Petrograd itself. It took responsibility for running the city, overseeing the delivery of food supplies, arresting the remaining tsarist police, and organizing the Red Guards to keep order. The Red Guards consisted of armed workers; each factory was expected to put one out of every ten employees into the Guards. The Soviet started a newspaper, Izvestia, which became the city’s, and the country’s, main source of information, especially since the other papers were often on strike. Moreover, other soviets quickly sprang up in almost every city and town in Russia, and even in many peasant villages. There were soldiers’ soviets throughout the army and sailors’ soviets at the naval bases and onboard the battleships. All looked to the Petrograd Soviet for guidance.

But the Menshevik and SR leaders did not want the Soviet to be the government of Russia. The soviets represented the working class and a large portion of the peasantry—the millions of young peasants who had been drafted into the army. Almost all Russian socialists, including most of the Bolsheviks who were currently in the capital, believed their country was still too economically backward for a socialist government, which is what direct rule by the soviets would mean. For one thing, the working class, the potential agent of a socialist revolution, was only a small proportion of the population, 80 percent of which was composed of peasants. To the Mensheviks and SRs, the February Revolution was Russia’s long-anticipated bourgeois revolution: The bourgeoisie, represented by the Provisional Government, had taken power, and it deserved the workers’ support. The job of the soviets, they believed, was to monitor the actions of the Provisional Government and put constant pressure on it to be more democratic; then, once the war was over, the Constituent Assembly would be elected and the socialist parties could start operating as a strong political opposition, much as the massive Social-Democratic Party (SPD) did in Germany. Eventually, after the bourgeoisie had industrialized Russia’s economy, it would be time for the now-majority working class, with the socialists at their head, to take power. This was the standard, accepted Marxist theory of the stages Russia needed to go through in order to reach socialism, and for the time being there were few, even among the Bolsheviks, who questioned it.

A Menshevik, Nikolai Sukhanov, summarized his party’s perspective: “The government that was to take the place of tsarism must be exclusively bourgeois. … This was the solution to be aimed at. Otherwise the overturn would fail and the revolution perish.”8

Despite the fact that it was the workers of Petrograd who had overthrown the autocracy, the Mensheviks and SRs adhered rigidly to this position. Sukhanov described a delegation of Soviet leaders who met with Miliukov and informed him that “the Soviet … would leave the formation of a provisional government to the bourgeois groups”:

Miliukov had taken very accurate bearings. He understood that without an accord from the Soviet no government could either arise or remain in existence. He understood that it was entirely within the power of the Executive Committee [of the Soviet] to give authority to a bourgeois regime or withhold it. He saw where the real strength lay. … And as for the “minimal” nature of our demands [complete freedom of speech, organization, etc.] and the general attitude taken by the Executive Committee … Miliukov had not expected such “moderation” and “good sense.” … He didn’t even think of concealing his satisfaction and pleasant surprise.9

Nevertheless, the Soviet and the Provisional Government occasionally acted at cross purposes. For example, most of the government ministers hoped to allow the imperial family to slip out of the country and go into exile, probably in Britain. But the Soviet insisted the tsar, tsarina, and their five children be placed under house arrest, where they could not be involved in any counter-revolutionary plots. The war soon became an area of major disagreements, but at first the socialists were willing to support the Provisional Government’s policy of keeping Russia in the conflict. Most of the Mensheviks and SRs, and all of the Bolsheviks, had opposed the war when the tsar was on the throne, but now they reasoned that Russian armies were fighting to defend the Revolution. Still, the Provisional Government thought the way to conduct the war was to make the army more disciplined, while the Soviet believed that making the army more democratic was the only way to inspire greater effort from the soldiers. Thus, on March 14, the Petrograd Soviet issued “Order Number One” to the troops: Military units were to be run by elected committees, and officers could issue commands only in battle. The fact that the Soviet believed it was entitled to give orders to the army without consulting the Provisional Government showed that it would occasionally act as a rival, not just a watchdog.

Despite these tensions, the first couple of months after the February Revolution were a time of unity and heady optimism. The autocracy had been overthrown almost without bloodshed. Russia had become, virtually overnight, perhaps the freest country in the world. There was complete freedom of speech, press, assembly, and religion. Everyone seemed to be involved in politics, and people read books, newspapers, and pamphlets voraciously. There was universal suffrage, including women. Equal rights were given to all Russia’s ethnic minorities, including Jews.

Still, as Vladimir Stankevich, an SR, recalled in his Memoirs, the true feelings of the upper classes were anything but optimistic:

Officially they celebrated, eulogized the revolution, cried “Hurrah!” to the fighters for freedom, adorned themselves with red ribbons, and marched under red banners. … Everyone said “we,” “our revolution,” “our victory,” and “our freedom.” But in their hearts, in their tête-à-têtes, they were horrified, trembled, felt themselves prisoners of a hostile elemental force that was traveling an unknown road. Unforgettable is the figure of Rodzianko [wealthy landowner, president of the Duma], that portly lord and imposing personage, when, preserving a majestic dignity but with an expression of deep suffering despair frozen on his pale face, he made his way through a crowd of disheveled soldiers in the corridor of the Taurida Palace [first meeting place of both the Petrograd Soviet and the Provisional Government]. … They say that the representatives of the Progressive Bloc [the Cadets and their allies] in their own homes wept with impotent despair.10

This “hostile, elemental force” was an awakening working class and peasantry. John Reed, an American journalist reporting on the Revolution, wrote,

[G]reat Russia was in labor, bearing a new world. The servants one used to treat like animals and pay next to nothing, were getting independent. … The waiters and hotel servants were organized and refused tips. …

All Russia was learning to read, and reading—politics, economics, history—because the people wanted to know. In every city, in most towns, along the front, each political faction had its newspaper—sometimes several. Hundreds of thousands of pamphlets were distributed by thousands of organizations, and poured into the armies, the villages, the factories, the streets. The thirst for education, so long thwarted, burst with the Revolution into a frenzy of expression. … Russia absorbed reading matter like hot sand drinks water, insatiable. …

Then the Talk … Lectures, debates, speeches … Meetings in the trenches at the front, in village squares, factories. … What a marvelous sight to see the Putilov factory [the largest in Petrograd] pour out its 40,000 to listen to Social Democrats, Socialist Revolutionaries, Anarchists, anybody, whatever they had to say, as long as they would talk! … In railway trains, street cars, always the spurting up of impromptu debate, everywhere. …

We came down to the front, … where gaunt and bootless men sickened in the mud of desperate trenches; and when they saw us they started up, with their pinched faces and the flesh showing blue through their torn clothing, demanding eagerly, “Did you bring anything to read?”11

All this freedom and politicization encouraged people to demand things that the Provisional Government was not willing to grant. Many ethnic minorities wanted more than equal rights—they wanted to secede from Russia and form their own independent countries. Peasants wanted the thing they had long dreamed of—land—and they began simply to take it. Throughout the country, peasants started to seize property belonging to the nobility. Workers wanted at least some say in how their factories were run, and many could see no reason why capitalists should retain control of the factories at all. And the vast majority of the Russian people were sick to death of the war.

But the Provisional Government was made up of men who believed in the sanctity of private property. They promised that the peasants would get more land eventually, once the Constituent Assembly was elected, but they strongly opposed peasant seizures. (This made no sense to the peasants; nobody had waited for a Constituent Assembly to overthrow the tsar, so why should they have to wait to take the land?) And while the Provisional Government did change the laws to allow workers complete freedom to form unions and conduct strikes, they supported the capitalists, who had no intention of sharing control of their plants with the workers, much less surrendering ownership.

As for the questions of the war and the rights of the subject nationalities, the members of the Provisional Government were ardent Russian nationalists and, in fact, imperialists. Far from being willing to tolerate the separation of non-Russian parts of the empire, they dreamed of conquering new territories as a result of the war. The Allies had made secret treaties with the tsar promising Russian control over Istanbul and other parts of the Ottoman Empire such as Armenia, as well as pieces of Austria-Hungary; as far as the Provisional Government was concerned, these treaties were still valid—despite the Soviet’s insistence that Russia renounce conquests and redefine the war effort as purely defensive. Poland had declared its independence, and the Provisional Government recognized it, but this was mainly because it had no choice: Poland was then under German occupation. On the other hand, Finland, Ukraine, and Russia’s Baltic provinces—Lithuania, Latvia, and Estonia—also sought independence, which the Provisional Government was determined to resist.

The war, however, was an extremely delicate subject for the Provisional Government. Anti-war feeling was very strong among the masses, and the Soviet reflected this mood. So, to avoid damaging relations with the Soviet, the Provisional Government publicly proclaimed “that the aim of free Russia is not domination of other nations, or seizure of their national possessions, or forcible occupation of foreign territories, but the establishment of a stable peace on the basis of the self-determination of peoples. The Russian people do not intend to increase its world power at the expense of other nations.”

But this statement did not actually reflect the Provisional Government’s plans.

“Peace, Land, and Bread”

On April 16, Lenin arrived in Petrograd. Stuck in Switzerland when the Revolution broke out, he had desperately looked for a way to get home. But with Europe at war, and hundreds of miles of German and Austro-Hungarian territory between Switzerland and Russia, it seemed hopeless. Then, Lenin received a strange offer: The German government would transport him and his fellow exiles in a special train across Germany to the Baltic Sea; from there they could make their way via Sweden to Russia. Why was the kaiser’s government willing to help a notorious revolutionary? General Erich Ludendorff, who, along with Paul von Hindenburg, had become a de facto military dictator, hoped that Lenin, as an outspoken anti-war socialist, would undermine Russia’s war effort and thus help Germany. Lenin realized this, and he worried that if he accepted, it might look like he was nothing but a German agent. But he hesitated for only a moment. Instead of being used by Ludendorff, Lenin figured, it would be the other way around; his plan, once he had returned to Russia, was nothing less than to lead a second, socialist, revolution there; and once the workers had taken power in Russia, he felt confident that the German working class would be inspired to follow suit. In the end, Ludendorff and all he represented would come crashing down. So Lenin, his wife Nadezhda Krupskaya, and several hundred Bolsheviks and Mensheviks (Martov took a later train) got on board and headed for the Revolution.

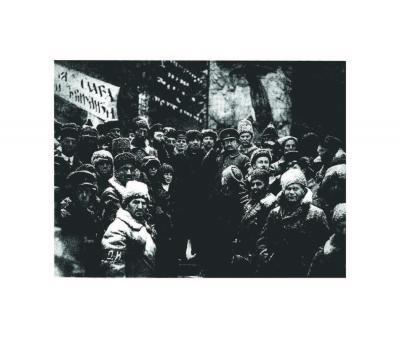

Lenin’s arrival at Petrograd’s Finland train station on the night of April 16 was a remarkable moment. The Menshevik Chkheidze, chairman of the Petrograd Soviet, was on hand to greet him in the station’s main waiting room. In the name of the Soviet Executive Committee, Chkheidze gave a short speech welcoming Lenin but also emphasizing the need for unity and for continuing the war against Germany now that it was supposedly aimed only at defending Russia’s new democracy. During the Menshevik leader’s speech, Lenin seemed to pay no attention, staring at the ceiling and fidgeting with a big bouquet of flowers someone had given him. As soon as Chkheidze had finished, he turned to the crowd of ordinary people who had also assembled at the station and, ignoring the delegation from the Executive Committee, addressed them:

Dear comrades, soldiers, sailors, and workers! I am happy to greet in your persons the victorious Russian Revolution, and greet you as the vanguard of the worldwide proletarian army. … The hour is not far distant when at the call of our comrade, Karl Liebknecht [leading German anti-war socialist], the peoples will turn their arms against their own capitalist exploiters. … The worldwide socialist revolution has already dawned. … Germany is seething. … Any day now the whole of European capitalism may crash. The Russian Revolution accomplished by you has prepared the way and opened a new epoch. Long live the worldwide socialist revolution!12

Walking out of the station, Lenin tried to get into an automobile, but the crowd lifted him onto an armored car and demanded he give another speech. There, illuminated by a searchlight that happened to be mounted nearby, he denounced the Menshevik and SR leaders of the Soviet as tools of the bourgeoisie and proclaimed, “We don’t need a parliamentary republic, we don’t need bourgeois democracy, we don’t need any government except the soviets of workers’, soldiers’, and farm-laborers’ deputies!”

When Lenin met with the Bolshevik organization in Petrograd, he presented his “April Theses,” which astounded them almost as much as they had the Mensheviks. Essentially, Lenin disagreed with virtually all Russian socialists on the nature of the Revolution of 1917. The workers and soldiers had overthrown tsarism, but because of the misleadership of the Mensheviks and SRs, they had allowed the bourgeoisie to take power through the Provisional Government. This was a mistake, Lenin insisted; the dual power must be ended, the Provisional Government overthrown and replaced with a government of the soviets. The war remained an imperialist conflict, and Russia’s participation in it should be opposed.

What Lenin was now arguing, in fact, was that the Russian Revolution could be transformed almost immediately into a socialist revolution. This was the theory that Trotsky had advanced back in 1906. (Trotsky was at that moment, with great difficulty, making his way from the United States to Russia.) To the standard objection made by other socialists (and at first by many of his own Bolsheviks) that Russia was too underdeveloped for socialism, Lenin, as we have seen, predicted that Europe as a whole was on the brink of revolution and only needed the Russian working class to take power in order to ignite socialist upheavals in Germany, Austria, France, Italy, and elsewhere. The Russian Revolution would be a sort of prelude to the main act: Once the European working class had taken power, socialism would become a global reality.

Lenin had to argue relentlessly to persuade the other Bolsheviks, but eventually they accepted his theses. Now their slogan became “All Power to the Soviets!” As Lenin noted, however, this could not be achieved overnight. For now, the Mensheviks and SRs were still in control of the soviets, and they refused to take power. The Bolsheviks’ job was patiently and persistently to argue with the workers and soldiers who had elected these more moderate socialists, to persuade them that the Mensheviks and SRs were wrong and the Bolsheviks right. As soon as the Bolsheviks won majority support in the soviets, it would be time to depose the Provisional Government. The support of the peasants in the villages was also essential; therefore, the Bolsheviks must endorse the peasants’ demand for land and offer an immediate solution to the war, which was consuming their sons, brothers, and husbands. By doing this the Bolsheviks would drive a wedge between the peasants and the Provisional Government, which insisted that the war must continue and kept telling the peasants to wait for the Constituent Assembly to give them land. So another appealing Bolshevik slogan was “Peace, Land, and Bread!”

On the war there now were three distinct positions: The Provisional Government wanted Russia to fight on to a complete victory for the Allies; the moderate socialist leaders of the Petrograd Soviet also wanted Russian troops to keep fighting, but simultaneously they called on both the Allies and Central Powers to negotiate an end to the war on the basis of “no annexations [conquests] and no indemnities”; the Bolsheviks called for socialist revolution in all the warring countries, encouraged Russian soldiers on the eastern front to fraternize with German and Austro-Hungarian soldiers, and insisted that Russia extricate itself from the conflict as soon as possible.

On the land issue, the differences were also clear. The Cadets regarded the peasant seizures as intolerable attacks on private property. They promised that the issue would be resolved once the Constituent Assembly met, but they hoped elections to the Assembly could be postponed until the war ended, which might take several more years. The moderate socialists were sympathetic to the peasants, but because they were afraid of antagonizing the bourgeoisie and the Provisional Government, they also opposed the seizures. The Bolsheviks, however, encouraged the peasants to go ahead and take the landlords’ estates for themselves.

In his memoirs, written in exile years later, Chernov, the leader of the SRs, regretfully recalled government-ordered attacks on peasants:

That was stark madness. There was no better means of demoralizing the army than to send it, with 90 percent of it peasants, to crush the movement of millions of its brethren. In Samara province the soldiers’ wives raised rebellion: “Let us go and mow the grain of the gentry; why are our husbands suffering for the third year?” The gentry brought a detachment of soldiers from Hvalynsk. But when the soldiers, who were peasants themselves, saw the peasants mowing the rich grain, they tried their hand at mowing; they were tired of their rifles. The peasants fed the soldiers, talked to them, and then set to work all the harder.

In Tambov province a military detachment came at the summons of Prince Vyazensky. It was greeted by a roar from the crowds: “What are you doing, coming to defend the prince, coming to beat your own fathers? Throw the devils into the river!” The commander took into his head to fire into the air. He was struck by a stone and ordered the troops to disperse the mob, but the soldiers did not stir. The officer spurred his horse and escaped from the enraged peasants by fording the river. His detachment scattered and let the crowd surround the prince, who was arrested. … At a nearby station he was lynched by a detachment of Siberian troops on their way to the front.13

In 1917, however, the SRs and Mensheviks, or least their leaders, believed the masses were naive and politically immature. Workers, soldiers, and peasants were impatient with the pace of change, but they had to be restrained, the moderate socialists believed, if the alliance with the bourgeoisie was to be maintained. They regarded Lenin and the Bolsheviks as dangerous and irresponsible demagogues who were cynically fanning the flames of discontent simply in order to acquire power.

Mounting Crises

In May a crisis occurred when the public learned that Miliukov, the foreign minister, had sent a note to the governments of the Allies reassuring them that Russia would not back out of its previous commitment to help defeat the Central Powers. Essentially, Miliukov was telling the Allies not to take the soviets’ call for a negotiated peace, or the Provisional Government’s own earlier statements renouncing conquests, too seriously. The goal remained total victory over the enemy and division of the spoils thereafter. The news of “Miliukov’s Note” unleashed a storm of outrage. Demonstrators took to the streets shouting “Down with Miliukov!” and “Down with the Imperialist Policy!” Some protestors carried banners calling for the overthrow of the Provisional Government itself, but most were not yet willing to go as far as the Bolsheviks. Instead, the Executive Committee of the Soviet worked out a compromise: The Provisional Government was reorganized, with the resignation of Miliukov and four other liberal ministers and the inclusion of five new socialist members from the Soviet. Kerensky, formerly the only socialist in the government, was given the important position of minister of war. The Provisional Government was now a coalition, with ten “capitalist” and six socialist ministers.

When Chkheidze, Tseretelli, Chernov, and the other new socialist ministers asked the Soviet to approve the coalition, a familiar but long-absent face was in the auditorium of the Smolny Institute. Leon Trotsky, the hero of 1905, had just arrived in Petrograd, with his wife, Natalia Sedova, and two sons, after a five-week journey across the ocean from New York. En route he and his family had been taken off their ship when it docked in Halifax, Nova Scotia. There British officials threw Trotsky into a camp for German prisoners of war, mostly sailors removed from U-boats. Immediately, he began distributing anti-war literature and making speeches in favor of revolution. When the British finally released Trotsky, the German prisoners gathered at the gate to send him off with a chorus of the Internationale.

Now the members of the Executive Committee asked Trotsky what he thought of the coalition. He replied by first observing that the Revolution “had opened a new epoch … of struggle, no longer of nation against nation, but of the suffering and oppressed classes against their rulers.” This remark annoyed the socialist ministers, who were committed to continuing the war and, indeed, believed that their participation in the Provisional Government would now guarantee its nonimperialist character. Trotsky then went on to denounce the coalition and demand instead that “our next move will be to transfer the whole power into the hands of the soviets.” Clearly, Trotsky was taking his stand with Lenin, and shortly thereafter he joined the Bolshevik Party.

Bolshevik ideas were rapidly catching on, but so far mainly in Petrograd; Lenin’s influence was not very widespread in the provinces as yet. This was shown by the results of the All-Russian Congress of Soviets, which met in Petrograd on June 16. The congress included representatives from 350 soviets throughout Russia, and it elected an All-Russian Executive Committee to be a national leadership for all the soviets. Of the delegates, 285 were SRs, 245 were Mensheviks, and only 105 were Bolsheviks. The new All-Russian Executive Committee, consequently, was dominated by Mensheviks and SRs, just like the Petrograd Executive Committee.

Now that the coalition had redefined the Russian war effort as strictly defensive, the Provisional Government decided it was time to launch a major military offensive to drive German and Austro-Hungarian troops out of Russian territory. Kerensky, the minister of war, and the other ministers, socialists and liberals alike, believed that Russian soldiers would now be willing to fight, but they were mistaken. After a few victories in late June, the offensive collapsed. Entire army units simply refused to go on fighting.

The defeat of the June offensive further undermined the credibility of the Provisional Government and increased the appeal of the Bolsheviks’ peace program. On July 16, a rebellion broke out in Petrograd. The Bolsheviks had called for a peaceful protest demonstration against the war, but the masses of angry workers, soldiers, and sailors who turned out on the streets of the capital, many with weapons, wanted to go much further: They called for the overthrow of the Provisional Government. For four days there were violent street clashes between the demonstrators and some units of the army that remained loyal to the government. The Bolsheviks were in a quandary. On the one hand, they believed an uprising at that time was premature; Bolsheviks did not yet have majority support in most soviets outside Petrograd, and a seizure of power in the capital alone would be isolated and eventually defeated. On the other hand, the Bolsheviks did not want to separate themselves from the masses when they were being shot down. So Lenin and the other Bolshevik leaders participated in the July Days, as they came to be known, while simultaneously attempting to restrain the rebels as much as possible.

The July Days were, nonetheless, a big setback for the Bolsheviks. The demonstrations were crushed, and thousands of workers and soldiers felt demoralized and defeated. Many Russians accepted the Mensheviks’ version of events:

The armed action of several regiments, led by unscrupulous agitators of the Bolshevik Party, and in some cases simply by adventurers, attracted into the streets, also, a section of the workers. All demanded, in a threatening manner, the overthrow of the Provisional Government and the transfer of all power to the control of the Soviets. …

The Taurida Palace, where the Central Executive Committees of the [soviets] were in session, was besieged with bayonets and machine guns. Violence was done to individual members of the committees, and even to Comrade Chernov.14

Groups of soldiers, joined by notorious spies and agents provocateurs, drove about the streets in stolen automobiles and fired upon citizens with rifles and machine guns.

As a result, there were scores of killed, hundreds of wounded, enormous losses through the strike, looted stores and residences, more bitterness against the workers by the petty bourgeoisie, and an alarming consolidation of counter-revolutionary forces. …

The Leninites [Bolsheviks] promised the masses an early peace and bread, and the masses followed them. Today, disillusioned with the Leninites, these masses may turn their wrath on all the socialists, and begin to listen to those who will … whisper all kinds of promises in their ears.

The Provisional Government accused the Bolsheviks of treason and denounced the party’s leaders as German agents. Trotsky was thrown into prison, and Lenin was forced to shave off his beard, don a disguise, and go into hiding in nearby Finland.

The Kornilov Affair

The July Days led to another reshuffling of the Provisional Government. More liberals resigned, more socialists joined the cabinet, and Kerensky replaced Lvov as prime minister. The Cadets, the middle class, landlords, and army officers were losing confidence in the Provisional Government, which they believed was incapable of controlling the masses. To them, the Soviet especially was a continuing source of disruption, and they began to feel that it should be disbanded. Landlords could no longer tolerate the growing wave of peasant land seizures, which the Provisional Government and the Soviet leaders opposed but were unable to prevent. Factory owners chafed at the assertiveness of their workers. Army officers had lost all control over their troops. Cadet politicians were besieged by anxious inquiries from Allied ambassadors, who feared Russia might soon pull out of the war.

The Congress of Trade and Industry, the main organization of Russian business, declared, “The Government, during the past months, has permitted the poisoning of the Russian people and the Russian army and the disruption of all discipline, thereby following the Soviets … who must bear the responsibility for the disgrace and humiliation of Russia and the Russian army.”

The propertied classes looked for leadership to General Lavr Kornilov, the commander of Russia’s armed forces. At the same time, Kerensky, whose domineering personality had enabled him to become a sort of boss of the Provisional Government, may have begun to dream of setting himself up as a dictator, also without the soviets.

In August a plot was hatched to crush the Petrograd Soviet. To this day the “Affair” remains shrouded in mystery, but it seems that at first Kornilov and Kerensky worked with each other; their plan was to bring dependable troops from the front to the capital and seize control. As Kornilov began to move on Petrograd, however, Kerensky suddenly turned against him and called on the people to “save the Revolution.” On September 9, with Kornilov’s soldiers only a few miles away, the people of Petrograd mobilized to defend their city and the soviets. The Bolsheviks were released from jail to help, and in fact they soon took charge of the whole effort. Arms were distributed, and trenches dug on the city’s outskirts. Bolshevik agitators slipped into Kornilov’s camp and pleaded with his soldiers not to fight against the Revolution. The result was a complete debacle for Kornilov. Before he could reach Petrograd, his forces simply melted away.

The Bolsheviks emerged from the Kornilov Affair with even greater prestige than they had enjoyed before the July Days. Kerensky, on the other hand, was now almost completely isolated. Mistrusted by the workers and soldiers, who suspected the truth about his secret dealings with Kornilov, he was also despised by the propertied classes for his lack of resolve.

The Affair convinced the masses that the Provisional Government was an empty shell, riddled with traitors to the Revolution, and that only the Soviet was capable of defending their interests. The Bolshevik slogan, “All Power to the Soviets!” was now widely embraced. Even some members of the other socialist parties started having second thoughts about their theory that the Russian Revolution could not go beyond the limits of bourgeois rule. Martov and a minority of the Mensheviks began to think that the soviets ought to take power, though most of his fellow Menshevik leaders—Chkheidze, Tseretelli, and the rest—still firmly rejected this idea. The Socialist Revolutionaries split completely. Many of the younger, more radical leaders supported peasant land seizures, opposed the war, and agreed with the Bolsheviks on soviet power. They formed their own faction, the Left SRs, while the older leaders, chief among them Victor Chernov, became known as the Right SRs.

The “October” Revolution

Early in September, new elections to the Petrograd Soviet were held in the city’s factories and army barracks. The result, announced on September 13, was a majority for the Bolsheviks. The Mensheviks and SRs on the Executive Committee were replaced by Bolsheviks, and Trotsky became the chairman of the Soviet. A week later the same thing happened in Moscow, and after that in city after city and throughout the army and navy. But the All-Russian Executive Committee, elected back in June with a Menshevik-SR majority, was still in place.

Lenin, who had emerged from hiding, now urged his party to prepare for the overthrow of the Provisional Government. The Second All-Russian Congress of Soviets would have to meet soon, and when it did, since the Bolsheviks now controlled almost all the local soviets, they expected to win a majority on the All-Russian Executive Committee too. Lenin believed that the moment for socialist revolution had arrived, and he worried that the Bolsheviks might let it pass without acting decisively. He felt sure that the workers would actively participate in an uprising, the peasants would support it, and the Provisional Government was powerless to prevent it. Above all, he believed, revolution was now possible in Europe; it needed only a signal from Russia. “The crisis has matured,” Lenin insisted. “The whole future of the Russian Revolution is at stake. … The whole future of the international workers’ revolution for socialism is at stake.”

Even so, two prominent Bolshevik leaders, Lev Kamenev and Grigori Zinoviev, opposed Lenin, warning that the masses would not support an insurrection; instead, they argued, the Bolsheviks should press for elections to the Constituent Assembly, which would then legally replace the Provisional Government. Lenin replied that Kamenev and Zinoviev had simply lost their nerve; if the Bolsheviks waited for the election and convening of the Constituent Assembly, which would take months, it might be too late. Trotsky supported Lenin, and it took all their efforts finally to persuade a majority of the Bolshevik Party to accept the necessity of insurrection.

Working feverishly, the Bolsheviks turned the Petrograd Soviet into the organizing center for the insurrection. The Smolny Institute was a beehive of activity, night and day; machine guns trundled down the halls as frightened Mensheviks and SRs peeked out of doorways. Trotsky personally headed the Soviet’s Military Revolutionary Committee, which made all the preparations for the overthrow of the Provisional Government, now scheduled to coincide with the opening of the Second All-Russian Congress of Soviets on November 7.

In the evening of November 6, armed detachments of Red Guards began to seize all government offices and communication centers in Petrograd: bridges, train stations, postal and telegraph offices. Revolutionary sailors from the nearby Kronstadt naval base moved the battleship Aurora to within firing range of the Winter Palace, where the Provisional Government met. Later that night, a crowd of Red Guards, soldiers, and sailors attacked the Winter Palace, which was guarded only by some students from a military school and a battalion of middle-class soldiers. After the Aurora fired a few blank shells, the palace’s defenders fled. Up the grand staircases the attackers ran until they reached the room where the Provisional Government sat glumly around a table. Bursting in, the leader, a small man in a floppy hat and pince-nez eyeglasses named Antonov-Ovseyenko, leaped up on the table and announced that the ministers were under arrest. The time was 2:10 in the morning of November 7.15 Kerensky had earlier slipped out and escaped in a car provided by the American embassy. The insurrection had won, and no one had been killed.

In the Smolny, the Congress of Soviets had begun to assemble on the previous evening. Out of 650 delegates from all over Russia, 390 were Bolsheviks and another 100 or so were Left SRs. There were only 80 Mensheviks altogether, and half of them belonged to Martov’s faction. When a straw poll was taken, 505 voted for transferring the government to the soviets. A new election was held for the Executive Committee; the Bolsheviks proposed that it be composed of 14 Bolsheviks, 7 SRs, and 3 Mensheviks; the Right SRs, whose comrades were under siege in the Winter Palace, refused to participate, but seven Left SRs agreed to do so. The Mensheviks could not decide. Finally, the news arrived that the Winter Palace had fallen and the Provisional Government was under arrest. At this point, the Right SRs and half the Mensheviks denounced the insurrection as illegal and walked out of the Congress, to the jeers of the other delegates. Martov was torn between his sympathy for a Soviet takeover and his personal ties to the other Menshevik leaders; finally he decided to join his friends outside the hall.

Trotsky writes,

One after another the representatives of the Right [the SR and Menshevik leaders] mount the tribune [go up to the podium]. … These socialists and democrats, having made a compromise by hook and crook with the imperialist bourgeoisie, flatly refuse to compromise with the people in revolt. … In the name of the Right Menshevik faction, Khinchuk … reads a declaration: “The military conspiracy of the Bolsheviks … will plunge the country into civil dissension, demolish the Constituent Assembly, threaten us with a military catastrophe, and lead to the triumph of the counter-revolution.” The sole way out: “open negotiations with the Provisional Government.” … Having learned nothing, these people propose to the Congress to cross off the insurrection and return to Kerensky. Through the uproar, bellowing, and even hissing, the words of the representative of the Right SRs are hardly distinguishable. The declaration of his party announces “the impossibility of work in collaboration” with the Bolsheviks, and declares the very Congress of Soviets … to be without authority.16

“What has taken place,” says Trotsky,

is an insurrection, not a conspiracy. An insurrection of the popular masses needs no justification. … Our insurrection has conquered, and now you propose to us: Renounce your victory; make a compromise. With whom? I ask: With whom ought we to make a compromise? With that pitiful handful who just went out? … There is no longer anybody in Russia who is for them. Are the millions of workers and peasants represented in this Congress, whom they are ready now as always to turn over … to the tender mercies of the bourgeoisie, are they to enter a compromise with these men? No, a compromise is no good here. To those who have gone out, and to all who make like proposals, we must say, “You are pitiful, isolated individuals; you are bankrupts; your role is played out. Go where you belong from now on—into the rubbish-can of history.”17

At 6:00 a.m. the exhausted delegates adjourned. That evening the Congress reconvened to decide three questions: ending the war, giving land to the peasants, and establishing a soviet government. Lenin gave a short speech and, after a tremendous ovation, declared simply, “We shall now proceed to construct the socialist order.” The Congress then approved a resolution on the war that proposed to all the countries involved an immediate armistice (cease-fire) followed by negotiations for a “just, democratic peace,” with no annexations or indemnities. The resolution went on to repudiate the secret treaties with the Allies, including all plans for the conquest of territory, and to promise that the treaties would be published for all the world to see the true imperialist nature of the war. It concluded by calling on workers in all the belligerent countries to overthrow capitalism as the only way to guarantee peace.18 A thrill ran through the hall as the delegates voted on the resolution; at that moment the international impact of what they were doing became apparent. Russia had broken out of the alliance system and was offering peace to a war-weary Europe; it was possible to believe a worldwide revolution might be in the offing.

Trotsky describes the moment:

The delegates were voting this time not for a resolution, not for a proclamation, but for a governmental act of immeasurable significance.

Listen, nations! The revolution offers you peace. It will be accused of violating treaties, but of this it is proud. To break up the leagues of bloody predation is the greatest historic service. The Bolsheviks have dared to do it. They alone have dared. Pride surges up of its own accord. Eyes shine. All are on their feet. No one is smoking now. It seems as though no one breathes. … “Suddenly, by common impulse,” the story will soon be told by John Reed, observer and participant, chronicler and poet of the insurrection, “we found ourselves on our feet, mumbling together into the smooth lifting unison of the Internationale. A grizzled old soldier was sobbing like a child. Alexandra Kollontai rapidly winked the tears back. The immense sound rolled through the halls, burst windows and doors and soared into the quiet sky.” Did it go altogether into the sky? Did it not go also to the autumn trenches, that hatchwork upon unhappy, crucified Europe, to her devastated cities and villages, to her mothers and wives in mourning? “Arise ye prisoners of starvation! Arise ye wretched of the earth!” The words of the song … fused with the decree of the government, and hence resounded with the force of a direct act. Everyone felt greater and more important in that hour. The heart of the revolution enlarged to the width of the whole world.19

The decree on land declared, “The landlords’ property in the land is annulled immediately and without any indemnity [payment] whatsoever”; all land was to be nationalized but “the right to use the land is accorded to all citizens … desiring to cultivate it with their own labor”; local soviets were to make sure that the landlords’ estates were divided fairly among the peasants according to need. As for the new government, the Congress elected a seven-member Council of People’s Commissars (it was felt that the title “minister” sounded too bourgeois), all Bolsheviks, with Lenin as chairman and Trotsky as commissar of foreign affairs. The Bolsheviks had wanted to share power with the Left SRs, but this group refused because it was still trying to mediate between the Soviet and its former comrades, the Right SRs, who were continuing their boycott. A few weeks later, however, the Left SRs gave up, and three of their leaders joined the Council.

The Constituent Assembly

The Right SRs and the Mensheviks now saw the upcoming elections to the Constituent Assembly as their chance to reverse the Soviet takeover. Late in November the elections were held, and on January 18, 1918, the Constituent Assembly gathered in Petrograd. Out of 707 delegates, there were 370 Right SRs, 40 Left SRs, 175 Bolsheviks, 15 Mensheviks, 17 Cadets, and about 80 belonging to smaller parties. The Right SRs were in control, and Victor Chernov was elected chairman of the Assembly. The Constituent Assembly immediately proclaimed itself the legitimate government of Russia.

But did it actually represent the people? The results seemed to indicate that the Right SRs, not the Bolsheviks, were supported by the majority of Russians—a reflection of the fact that more than 80 percent of the population was made up of peasants, who would naturally tend to vote for a party that stood in the tradition of populism and peasant revolution. But this was misleading. Russians voted for party lists, not individual candidates; in other words, a peasant, say, who wanted to vote for the SRs would vote for a whole list of candidates that the party’s leadership had previously prepared. The problem was, the SR list was drawn up by the more conservative leaders before the party split into Right SRs and Left SRs. Only in a few districts did the Left SRs manage to put out separate lists, hence the 40 Left SRs who did get elected. Elsewhere, however, peasants had no alternative but to vote for the official list of a party that was now actually two parties (obviously, peasants could vote for any party they wanted, and many voted for the Bolsheviks, but most stuck with the party they knew: the SRs). But since the Right SRs had opposed land seizures and supported the continuation of the war—positions that were deeply unpopular among the peasantry—it is doubtful they still represented their constituents by the fall of 1917, whereas it is fairly certain that the Left SRs more accurately reflected the peasant mood at that point. And in fact, in those few districts in which the Left SRs ran separately, they beat the Right SRs by overwhelming margins.20

The Bolsheviks not only regarded the Constituent Assembly as unrepresentative, but also as a superfluous and potentially counter-revolutionary body. Superfluous because the soviets were already functioning as a popular and a more democratic government, with closer ties to the workers and peasants. Potentially counter-revolutionary, because it was clear that some of the moderate socialists hoped to use it as a base for overthrowing the Soviet government, with violence if necessary. So, a day after the Constituent Assembly convened, Bolshevik soldiers came into the meeting hall and told the delegates to go home.

An indication of how little popular support there was for the Assembly is that its dispersal occasioned no mass protests and in fact was barely noticed in Russia. Outside Russia, however, the news was taken as proof that the Bolsheviks planned to establish a dictatorship.

The Treaty of Brest-Litovsk

The Bolsheviks’ peace program proved difficult to implement. The Allies ignored Russia’s appeal for an armistice and negotiations. Germany agreed to a temporary cease-fire in December 1917, and negotiation began in the border town of Brest-Litovsk. But the German negotiators made harsh demands: In return for peace, Russia must surrender vast amounts of territory and natural resources. These terms were catastrophic. Trotsky, the Bolsheviks’ chief negotiator, stalled for time and meanwhile appealed over the heads of the kaiser’s officials to the German working class, calling on them to support the Russian Revolution and pressure their government to back down.

These appeals had an impact: In January 1918, 500,000 German metal workers went on strike in solidarity with the Bolsheviks. The strikes spread, and soon a million German workers had walked off their jobs to protest their government’s aggression against Soviet Russia. But the strike movement was crushed, and Russia had either to accept or reject Germany’s ultimatum. Rejection meant the war would go on. The Left SRs, as well as some Bolsheviks, argued for fighting, but Lenin replied that this was impossible; the Russian army had already “voted with its feet”—that is, millions of soldiers were simply walking away from the front, going home. Finally, on March 3, 1918, the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk was signed. Germany occupied Lithuania, Latvia, and Estonia, but its most important acquisition was Ukraine, which contained some of the country’s richest farmland as well as most of its iron and coal and much of its industry. Russia was also required to pay a huge indemnity.

Lenin argued that the treaty was only a temporary setback. He was sure the German working class would recover from its defeat in January and, in a short time, bring down the kaiser and annul the treaty—which is exactly what happened eight months later. In the meantime, however, the effects were devastating. Without grain and coal from Ukraine, factories had to shut down from lack of fuel, and food shortages began to approach the level of famine. Nearly half the factory workers in Petrograd were forced to leave the city and forage for food in the countryside. The political repercussions were also ominous. The Left SRs left the government in protest over the treaty, leaving the Bolsheviks to govern alone. This was not what Lenin and the Bolsheviks had intended or foreseen.

State and Revolution

While hiding out after the July Days, Lenin wrote a long essay, “The State and Revolution,” in which he discussed the Marxist theory of the state and speculated about what kind of government Russia would have after the soviets took power. He declared that most government jobs could be “performed by every literate person” and that official positions “can (and must) be stripped of every shadow of privilege, of every semblance of ‘official grandeur.’” In the future workers’ state, Lenin insisted, all officials will be “elected and subject to recall at any time, their salaries reduced to the level of ordinary workmen’s wages.” Every worker and peasant will participate in governing; there will be no special group of rulers. Lenin wrote, “The mass of the population will rise to taking an independent part, not only in voting and elections, but also in the everyday administration of the State,” that is, “every cook will govern.”

In the first place, however, when the working class succeeded in taking over, Lenin was sure that the rich and powerful would never surrender without a fight. So, he declared, soviet power would mean that “simultaneously with an immense expansion of democracy, which for the first time becomes democracy for the poor, democracy for the people, and not democracy for the moneybags, the dictatorship of the proletariat imposes a series of restrictions on the freedom of the oppressors, the exploiters, the capitalists. … Their resistance must be crushed by force” if they attempted to mount armed resistance or conduct economic sabotage against the workers’ state, as Lenin predicted.

The Bolsheviks did not start with the idea of suppressing other parties or even of disfranchising the old elite. Lenin repeatedly insisted that depriving the former ruling class of the right to vote and of civil liberties was not a principle of Bolshevism nor need it be necessary in revolutions abroad. It was the inability of the capitalists and landowners to reconcile themselves to the rule of workers and peasants that drove them into open rebellion. Capitalists sabotaged their own plants, fled the cities, and, with the aristocracy and tsarist army officers, launched a counter-revolutionary civil war to overturn Soviet power. Tragically, this counter-revolution was soon joined by most of the leadership of the Mensheviks and SRs as well. Even the Left SRs eventually went into open, armed rebellion after Brest-Litovsk.

The Marxist term “dictatorship of the proletariat” had never meant rule by one person or a small oligarchy—dictatorship in the modern sense. It meant essentially that the majority of the people—the proletariat, or in Russia, the proletariat and peasantry—would have to impose their rule, “dictatorially,” on those they had overthrown—the capitalists and other members of the privileged minority. If they did not ruthlessly suppress all attempts at counter-revolution, then capitalism would be restored and the revolution would be drowned in blood, as the Paris Commune had been in 1871. For the vast majority, however, it was assumed that the widest possible democracy and the maximum freedom would prevail.

The soviet state that was born on November 7, 1917, came the closest of any state in history to abolishing the distinction between rulers and ruled. The soviets combined representative and direct democracy in a new form that might be called delegate democracy, in which governance was exercised not by distant “representatives,” but by delegates closely tied to small units of electors and immediately recallable if they violated their mandates. Power flowed from the bottom up in a pyramidal structure of workplace, district, city, and national soviets. Moreover, electors, meeting in frequent assemblies, were organized as workers in their workplaces, a natural locus for discussion and debate with a tendency to generate a sense of solidarity and common purpose, not as atomized “voters” inhabiting given geographical units with little or no communication among themselves, almost never assembling to discuss their political choices but instead trooping to the polls every few years to choose among representatives of the ruling class (or, just as frequently in our country, abstaining as a result of disinterest, alienation, or ignorance).

Lenin and the other Bolsheviks took it for granted that Russia would be governed by the workers through the soviets, and that within the soviets there would always be free and open debates, frequent elections, and a multitude of political parties besides their own. Tragically, however, none of these expectations were to be realized.

For six months or so after November 7, the soviet state functioned more or less as Lenin had envisioned. But less than a year after the October Revolution, Soviet Russia had become an authoritarian one-party state. How and why this happened will be the subject of a subsequent article.

Footnotes

1. Rosa Luxemburg, The Russian Revolution and Leninism or Marxism? (Ann Arbor, 1961), 80. The reference is to Ulrich von Hutten, German poet and scholar, who led the Protestant Knights’ Revolt of 1522, which inspired the great German Peasants’ War of 1524-1526.

2. Rasputin’s influence stemmed from his role as a “faith healer.” The tsar and tsarina’s son, Alexander, was afflicted with hemophilia, and Rasputin was apparently able to stop the boy’s bleeding with hypnosis.

3. In 1903 two factions emerged within Russia’s newly formed Marxist organization, the Russian Social Democratic Labor Party (RSDLP): the Bolsheviks and the Mensheviks. In 1912 they became separate parties. Initially, they differed over how the RSDLP should be constituted. The Bolsheviks insisted on stringent requirements for membership (Lenin said he wanted a party of “professional [not amateurish] revolutionaries,” members with a high degree of political sophistication and revolutionary expertise), while the Mensheviks favored a looser organization. Soon there were other political differences. The defeat of the 1905 Revolution was blamed by the Bolsheviks on the betrayal of middle-class liberals, while the Mensheviks argued that the workers, by being too militant, had scared the liberals into making their peace with the autocracy. The SRs were a non-Marxist socialist party rooted in the nineteenth-century Russian Populist, or Narodnik, movement. The Narodniks had advocated peasant revolution and waged a campaign of assassination against tsarist officials. But by 1917 they had become more moderate and committed to supporting Russia’s liberals, much like the Mensheviks.

4. Since Russia was still using the Old Style dating system, Feb. 23 was the day the Revolution began according to the Russian calendar. So, even though Russia adopted the New Style calendar a year later, the overthrow of the autocracy has always been known as the February Revolution.

5. Cossacks were a special force of fierce horsemen used by the tsars to suppress riots, strikes, and revolts.

6. The Duma was a virtually powerless parliament created by the tsar in response to the Revolution of 1905.

7. “Soviet” is the Russian word for “council.” Soviets had sprung up during the 1905 Revolution, but were suppressed with the revolution’s defeat.

8. N.N. Sukhanov, The Russian Revolution 1917: A Personal Record (Princeton University Press, 1984), 6-7. Along with Trotsky’s The History of the Russian Revolution, Sukhanov’s book is a vivid and invaluable first-hand narrative, albeit with a very different interpretation.

9. Sukhanov, 124.

10. Quoted in Tony Cliff, Lenin, vol. 2 (London: Pluto Press, 1976), 90.

11. John Reed, Ten Days that Shook the World (Penguin, 1960), 14-15.

12. Quoted in Sukhanov, 273.

13. Quoted in Cliff, 214.

14. Chernov, when he came out to speak to the crowd, was accosted by a group of sailors, one of whom yelled at him, “Take power, you son of a bitch!” Trotsky then appeared and persuaded the sailors to let him go.

15. Old Style, Oct. 25—hence the name, October Revolution.

16. Leon Trotsky, The Russian Revolution: The Overthrow of Tzarism and the Triumph of the Soviets (Doubleday and Co., 1959), 443-444.

17. Trotsky, 446.

18. Back in March the Menshevik and SR leaders of the Soviet had passed a similar resolution, but its call for revolution was aimed at the Central Powers only. In November, having overthrown capitalism in Russia, the Bolsheviks thought they were in a stronger position to ask workers in other countries to do the same.

19. Trotsky, 462.

20. Oliver Radkey, author of the definitive work in English on the Constituent Assembly elections, Russia Goes to the Polls (Harvard University Press, 1950), published evidence in a 1987 addendum that indicated the SRs had won a plurality, not a majority, and that peasant support for the program of the Bolsheviks and Left SRs was actually much broader than the voting indicated. Prior to the election, the leaders of the Right SRs manipulated the ballots to make sure that the Lefts would be substantially under-represented. It was also significant that peasants who lived near cities, garrisons, and railroads, and were therefore more likely to understand what the Bolsheviks and Left SRs stood for, voted for those two parties by large margins.

Bosheviks and democracy

On paper, the soviets were to be the only body elected directly by voters. The electorate was limited to workers and peasants. All other elections were indirect, including to the highest level. Anyone who was not a worker or a peasant was disenfranchised. The Bolsheviks did not believe in universal suffrage or direct elections of the governing class.

In reality, the soviets withered within one year of the revolution, replaced by a party dictatorship, but had they survived,they would not have been democratic.

A Constituent Assembly would have been more democratic and if the one the Bolsheviks dissolved was no longer representative, the Bolsheviks should have called for new elections.

As far as I know, the Bolsheviks never gave a thought to doing this because once they were in power,they had no intention of giving up power no matter what.