[This article is part of a debate, responding to this article by Jeanette Habel and Michael Löwy.]

[This article is part of a debate, responding to this article by Jeanette Habel and Michael Löwy.]

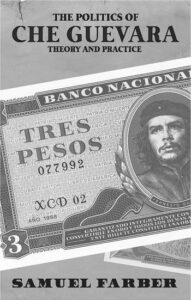

It is unfortunate that seven years have passed since my book, The Politics of Che Guevara. Theory and Practice, was published by Haymarket Books (it was also translated into French by the editorial house Syllepse under the title Che Guevara. Ombres et Lumieres D’Un Revolutionnaire in 2017). Thus, it is unlikely that most of the readers of this New Politics article remember or are familiar with that book’s contents. Otherwise, they would immediately detect the falsehoods and quotations out of context that these authors attribute to me for the purpose of delegitimating me as a marginal sectarian intent on slandering Ernesto (Che) Guevara. Thus, for example, Habel and Löwy cite me in a distorted manner dismissing Che Guevara as “a failed quixotic figure.” But this is the final sentence of a paragraph that presents a far more nuanced interpretation of Guevara and his impact in today’s Cuba:

It is ironic that, politically, he has become less relevant in today’s Cuba than he is in other countries around the world. Nevertheless, he continues to exercise a subtle but real influence on Cuba’s political culture—not as a source of specific programmatic or political proposals, but as a cultural model of sacrifice and idealism. In that limited sense, the official slogan “seremos como el Che” (we shall be like Che), chanted regularly by Cuban schoolchildren, probably has a diffuse but significant influence over the popular imagination, even if most Cubans also think of Che as a failed quixotic figure. (XV)

Moreover, when I analyze the political and social composition of the leadership of the 26th of July Movement, I never use the concepts and phrases “petty bourgeois” and “adventurer,” terms invented by the authors of the review to portray me as somebody that should not be taken seriously. The concept that I have used throughout some sixty years of researching and writing about Cuba is classlessness. Certainly, the movement’s leaders originally came from diverse social classes and strata, but most of them had not participated in the social and political life of those groups, which considerably diminished the ideological and normative influence that those groups may have had over them, and to that degree not only liberated them from those influences, but also made them freer and more available to adopt the politics of rebellion and insurrection. Of course, there were exceptions to this general tendency, as in the cases of Frank País, who had been very involved in the activities of the Baptist Church in Santiago de Cuba, and of Crescencio Pérez, the leader of peasant organizations who joined the Rebel Army and played a very important role in the Sierra Maestra, but no significant role at all after the victory of the revolution in 1959.

I also maintain in my book that the old pro-Moscow Cuban Communist Party (PSP) had a significant number of workers in its ranks. In 1956, the PSP conducted an internal study that showed that 15% of Cuban unions were led by members of the PSP or by leaders that collaborated with that party (Jorge Ibarra, Prologue to Revolution: Cuba, 1898 trans. Marjorie Moore. Boulder, Colorado, Riemer, 1998, 170). Similarly, the PSP won 10 percent of local leaderships in the elections of the Spring of 1959, (although we must bear in mind that there was also a sector among the 26th of July unionists who sympathized with the Communists). These were the only free and pluralist elections held in Cuba at a national level after the revolutionary victory. But the fact that there had been a significant worker presence in the PSP does not mean, and I never said, although Habel and Löwy attribute it to me, that the PSP had been a workers’ party. It was a party highly controlled by a bureaucracy, under a supposed “democratic centralism,” that had a lot of centralism, but no democracy at all, and in which some of its most important leaders, were of working-class origin and/or were active unionists.

The traditional distinction between reform and revolution, which originated in the disputes between social democracy and revolutionary Marxism at the end of the nineteenth century and beginning of the twentieth century, does not apply to the Communist parties under Stalin’s control starting at the end of the twenties. It certainly does not apply to the analysis of the Cuban PSP. The Cuban Communists generally followed Moscow’s guidelines, acting as ultra-leftists and sectarians at certain times such as the so-called Third Period (1928-1935)—that had disastrous results for the 1933 Cuban Revolution and contributed significantly to its failure—as well as political opportunists and wheeler-dealers together with the rest of the Latin American Communist parties, in other periods. It is worth noting that throughout all these stages, Cuban Communists had the same principal political leaders with relatively few purged or leaving the party.

During the Cuban Revolution, no important figure in the PSP showed any inclination or tendency to preserve the capitalist status quo. None of them broke with Fidel Castro when the Cuban leader announced the “socialist” character of the revolution in April of 1961, as was the case with almost all of the authentically reformist Cuban political leaders who had broken with the regime even before that declaration. In fact, as I show in detail in the fifth chapter of my book The Origins of the Cuban Revolution Reconsidered (University of North Carolina Press, 2006, 137-166), in the early months of the revolutionary period, the PSP maintained a much more radical position than Fidel Castro, though the “Maximum Leader” later surpassed the PSP’s radicalism. In this new stage, the PSP began to behave more cautiously than Fidel Castro, although it usually ended supporting the anti-capitalist measures adopted by the Maximum Leader. Even more important is the fact that the PSP joined together with the Directorio Revolucionario (Revolutionary Directorate) and Castro’s Movimiento 26 de Julio organization to establish the new Cuban Communist Party in the sixties where it played a very important role through leading figures such as Carlos Rafael Rodríguez. Considering these facts, it makes no sense to refer to the Cuban Communists as reformists in the sense that this term acquired in twentieth century Marxism.

The Political Evolution of Ernesto “Che” Guevara

For Habel and Löwy, my discussion of the Bohemian origins of Che Guevara in my book’s first chapter is pointless and irrelevant. Nevertheless, for me it is part of an effort to trace the origins of the great emphasis that Che Guevara, as different from other leaders of the Cuban Revolution, placed on moral incentives. As I explain in my book, all the revolutionary leaders eventually adopted a de facto policy of moral incentives due to the absence of material goods—caused as much by the criminal U.S. blockade as by the very bad and inefficient state administration—to motivate workers to put forth a serious productive effort in their workplaces.

Nevertheless, for Che Guevara, the moral incentives were not merely a practical matter that depended on the existing conjuncture. They were rather a product of his worldview that was developed initially in a home where the acquisition and possession of material goods was not a central value of his upper-class family with a certain tendency towards downward social mobility. Che Guevara had already demonstrated in his childhood and adolescence an inclination towards asceticism, as indicated by his great admiration for Gandhi, who aside from the central role he played in India’s independence, was perhaps the best-known twentieth century ascetic. Che’s asceticism expressed itself in a different manner in his adult life, but he never abandoned that outlook. A very illustrative example was the reflection he discussed during a meeting with the principal managers of the Ministry of Industry in 1964, related to the difference between Cuba, where a TV set that did not work well was a problem, and Vietnam where there was no television at all. According to Guevara, the development of consciousness allowed for the substitution of what he considered “secondary comforts” (comodidades secundarias) that had been converted into part of the life of the individual, but that expressed a need that society’s general education could have eliminated (Che Guevara, Apuntes Cíiticos a la Economía Política, edited by María del Carmen Ariet García, Ocean Press, 2006, 304). It is worth underlining that Che Guevara was not merely arguing that in crisis situations, people had to resign themselves to not obtaining certain goods and benefits, and that the revolutionary conscience would facilitate such resignation. His argument went much farther and proposed an even deeper political and even philosophical perspective that people be educated not to desire such goods by reverting to a previous period when those needs did not yet exist.

The bohemian life of Guevara’s family in Buenos Aires tends to be a phenomenon of rich countries such as France, Italy, the United States, and the Argentina of the childhood and adolescence of Che Guevara (born in 1928) when it was still considered one of the richest countries in the world and certainly the richest country in Latin America. But the bohemian life, in the sense of a cultural rejection of the acquisitive values of advanced capitalism did not exist in Cuba. In fact, in the decades of the forties and fifties, the term “bohemian” was applied in Cuba almost exclusively to the night life of cafes, restaurants, and cabarets, and to the people that very often for reasons of employment (artists, waiters, journalists, newspaper and service workers in general) went to those places as part of their social life.

For ideological and political reasons, Che Guevara as well as the other revolutionary leaders limited themselves to material and moral incentives and completely ignored the additional alternative of political incentives such as workers self-management. This would have meant the possibility of being able to discuss and take democratic decisions from below with respect to production and the management of workplaces. Those types of political incentives could have been a remedy for the apathy and indifference of the workers in the bureaucratic systems existing in the USSR and Eastern Europe, and that continue to prevail in Cuba.

Given the total absence of democracy, moral incentives and the so-called consciousness were a way of making workers responsible for their assigned tasks, without having the power to decide what is to be done, and how, in their places of employment, and without being able to count on the unions to defend their rights and interests. These had stopped being organizations whose purpose was to defend the rights and interests of the workers to gradually become, as we shall see below, arms of the state and of the bureaucratic administrations after the historic workers’ congress of November 1959.

With respect to guerrilla warfare, we can appreciate how Che Guevara’s political strategy meant a “from above” and “from outside” relationship with the peasantry. Thus, for example, Guevara cited approvingly a fragment of the Second Declaration of Havana of February 4, 1962, stipulating that as a result of the ignorance in which they have been kept and the isolation in which they lived, the peasantry needed the political and revolutionary leadership of the working class and the revolutionary intellectuals, [and consequently, the party that represents that vanguard] (cited by Ernesto “Che” Guevara in “La Guerra de Guerrillas: Un Método” in Rolando E. Bonachea and Nelson P. Valdés (editors): Che: Selected Works of Ernesto Guevara, Cambridge, Mass., 1969, 91). And in his treatise on guerrilla warfare of 1960, Guevara himself rejected the idea that democratic discussion and decision making was applicable to the various aspects of guerrilla life aside from combat itself. He did recognize that it was necessary to create organizations to establish rules for the peasants in liberated areas, but never formulated mechanisms of democratic representation so peasants could learn self-government in practice. (Che Guevara, Guerrilla Warfare, Third Edition, edited by Brian Loveman and Thomas M. Davies, Jr., Wilmington, DE: SR Books, 1977, 108.)

Che Guevara’s Communism

It was in the reformist Guatemala of the 1950s led by Jacobo Arbenz, the democratically elected president overthrown by the open intervention of the CIA, that Guevara became a Communist, although he refused to join the local Communist Party (Partido Guatemalteco del Trabajo or PGT) for several reasons, but especially because the PGT, which controlled the government workers’ union, demanded that he join the party as a condition of obtaining a government job, a condition that Guevara rejected with justified indignation. After joining the ranks of the 26th of July Movement in Mexico City, Guevara participated in and was part of the small group that survived the landing of the boat Granma in Cuba in December 1956. The Argentinian distinguished himself in the guerrilla struggle in the Sierra Maestra and rose to the rank of Comandante, the highest of all. Already in the Sierra, although Guevara never joined the old Cuban Communist Party (PSP), he began to collaborate with that organization. Towards the end of 1957, when Guevara founded his first school for the political instruction of cadres in the Sierra Maestra, he asked the PSP to send him his first political instructor. The PSP sent Pablo Ribalta, a young but politically experienced Black Cuban Communist who years later, after the Rebel Army’s victory, was appointed Cuban Ambassador to Tanzania. In this way, Ribalta became the principal contact with Havana when Che Guevara became involved in the guerrilla war in the Congo. (Jon Lee Anderson, Che Guevara. A Revolutionary Life, 296-97).

In contrast with other leaders of the 26th of July Movement, Guevara was very open with respect to his political views. For example, Che entered a dialogue with “Daniel” (Comandante René Ramos Latour) whose politics were described by Paco Ignacio Taibo as “radical workerist and nationalist,” who later died in combat in the Sierra Maestra. In a letter that Che wrote to “Daniel” on December 14, 1957, that Guevara later described as “rather idiotic” but without explaining why it was so, Che told “Daniel” that “because of my ideological background I belong to those who believe that the solution to the world’s problems are behind the so-called Iron Curtain and I see this [July 26] Movement as one of the many, provoked by the eagerness of the bourgeoisie, to get rid of the economic chains of imperialism.” In the same letter, Guevara continues describing Fidel Castro as an authentic leader of the left-wing of the bourgeoisie, but who possesses qualities that place him well above his class. He also praises Fidel Castro for important actions that he had recently taken with respect to opportunist sectors of the opposition to Batista. Che admitted feeling ashamed for not having anticipated that Fidel Castro could take those actions. (Carlos Franqui, Diario de la Revolución Cubana, Paris: Ruedo Ibérico, 362, and Paco Ignacio Taibo II, Ernesto Guevara también conocido como el Che, México, D.F.: Planeta, Joaquín Mortiz, 1996, 188.)

The close collaboration of Che Guevara with the old PSP lasted almost four years, which included the critical years of the consolidation of the Cuban Communist system. At the beginning of 1959, there were three tendencies within the revolutionary government: the liberal tendency, headed by President Manuel Urrutia and various ministers such as Roberto Agramonte and Elena Mederos. There was a revolutionary nationalist tendency described by Paco Ignacio Taibo II (op. cit., 354) as a leftist sector that combined “anti-imperialism with a strong critique of the communists who were considered conservative and sectarian.” This anti-imperialist group included David Salvador, principal leader of the CTC (Cuban Workers Confederation), Carlos Franqui, editor of the daily newspaper Revolución, organ of the 26th of July Movement, and other important leaders of the 26th of July Movement such as Marcelo Fernández and Faustino Pérez. The third group was composed of an alliance of several important revolutionary leaders, such as Che Guevara and Raúl Castro (chief of the Armed Forces), with the PSP. Meanwhile, Fidel Castro pretended to abstain from these internal regime struggles, allowing for example the polemics between Revolución and the PSP, although in fact he had frequent meetings in secret with the group headed by Che Guevara, Raúl Castro, and leaders of the PSP at Guevara’s residence in Tarará Beach to prepare the agrarian reform law adopted in May of 1959. It is worth noting that none of the members of the revolutionary nationalist tendency were invited to these meetings.

A series of events that took place beginning in September of 1959 and through 1960 clearly pointed to the end of the open and pluralist stage of the Cuban Revolution. On September 14, 1959, Euclides Vázquez Candela, one of the principal editors of Revolución, ended his newspaper’s polemics with the PSP. On October 1, Alexander Alekseev, an agent of Soviet intelligence posing as a journalist and later as a diplomat, arrived in Havana as an unofficial envoy of Moscow to the revolutionary leadership, and after meeting with some of the principal leaders of the PSP, had a meeting with Che Guevara (Jon Lee Anderson, op. cit., 429, 437). Later in October, Major Huber Matos, military chief of Camaguey province in eastern Cuba and a former schoolteacher who had fought against the Batista dictatorship in the Sierra Maestra, resigned his position in protest against what he denounced as the increasing Communist influence in Fidel Castro’s regime. Reacting with great fury, the Maximum Leader accused Matos of treason, which led to a twenty-year prison sentence, in a trial where proof that Matos had conspired or incited violence against the revolutionary government was never presented. Matos was not freed until 1979 when he had completed his sentence in its entirety.

The closing of the pluralist stage of the Cuban Revolution continued with the elimination of the independence of Cuban labor unions. In November of 1959, the CTC (Confederation of Cuban Workers) celebrated its tenth congress. When the election of delegates that would attend the congress took place in early November, it became clear that the results would be like the union elections that took place in the spring and that based on their small vote, the Cuban Communists would not be included in the leadership of the CTC. This provoked a personal intervention by Fidel Castro to ensure that the elected leadership would be favorable to the Communists. Even though the Communist leaders were not included in the new leadership slate, the so-called unitarian leaders of the CTC led by Jesús Soto that were allied to the Communists obtained the new dominating position in the CTC. Shortly thereafter, approximately half of the union leaders hostile to the PSP were purged in assemblies that were far from democratic, and some ended up in prison. This purging process opened the door to Soviet-style state control of the unions that culminated in the eleventh congress celebrated in November of 1961. In contrast to the debates of the tenth congress in November of 1959, this was the congress of unanimity that elected without any opposition, the old Stalinist union leader Lázaro Peña as Secretary General.

As part of the offensive against all autonomous and pluralist social and political expressions in Cuba, Fidel Castro’s government lashed out against both Black and women’s independent organizations. Black associations used to take the form of mutual aid organizations. Carlos Moore relates how in one of those organizations formed by plain working class people and called ”Amantes del Progreso” (Lovers of Progress), Black men regularly got together to drink and discuss political questions, help children with their homework, and to study Black Cuban history, a subject matter virtually ignored by the public education system (Carlos Moore, Pichón: A Memoir; Race and Revolution in Castro’s Cuba, Chicago: Lawrence Hill Books, 2008, 45-46). Sometime during 1959, revolutionary leaders decided to eliminate this source of independent power. Shortly after Juan René Betancourt, a well-known Black intellectual who was acting as provisional supervisor of the National Federation of Negro Societies, informed the government that the seventh national convention of that organization had been programmed for the end of November 1959, he unexpectedly found out through a radio program that he had resigned from his position “due to the pressure of other obligations.” This was the beginning of a process that by the mid-sixties had eliminated the independent associations of people of color as a vital force in Black Cuban society. (Juan René Betancourt, “Castro and the Cuban Negro,” Crisis 68, no. 5 [1961]: 271, 273.)

Something similar happened with the situation of Cuban women. This involved the revolutionary government’s creation of the Federation of Cuban Women (FMC) as one of its various “mass organizations” (later converted into the transmission belts for the single party) that translated into the compulsory dissolution of 920 independent women’s organizations that had existed in Cuba before the revolution. Because the Cuban women’s movement had disappeared twenty years earlier, the government achieved its purposes without much resistance, in contrast with the struggles and purges that took place in the union movement in 1959 and 1960. (Lois M. Smith and Alfred Padula, Sex and Revolution: Women in Socialist Cuba, New York: Oxford University Press, 1996, 32.) Finally, beginning in May of 1960, the revolutionary government eliminated all significant independent newspapers such as the right-wing Diario de La Marina and the liberal Prensa Libre. The weekly Bohemia, the most important Cuban publication that followed a left liberal and social democratic orientation, but hostile to the Soviet bloc and to the PSP, was taken over by elements following the government’s orientation. Its veteran editor, Miguel Angel Quevedo, a sympathizer of Fidel Castro for many years, had to leave the country. As one well-known columnist put it, the hour of unanimity had arrived.

We don’t know the degree to which Che Guevara was directly involved in these very important events, but it is well established that aside from his non-public objections to the way the revolutionary government treated Huber Matos, he certainly supported, without making any public criticism, the radical anti-democratic changes that took place in the critical period from September 1959 to the summer of 1960. In any case, it is quite clear that as one of the principal government leaders, Che Guevara was politically responsible for the turn that the government took in those days.

With respect to the unions, Che Guevara followed a policy very close to the one that the CTC adopted after November 1959. As the Minister of Industry, he declared in June of 1961 that Cuban workers should accustom themselves to a collectivist regime and could therefore not participate in strikes (Ernesto Che Guevara, Revolución. June 27, 1961). Che Guevara was expressing in his own words the notion that given that the Cuban state was a workers’ state, it was impossible for any conflict of interests to exist between the workers and the state. This certainly ignored the persistence of class differences and the hierarchical division of labor under Cuban “socialism.” Years later, when he was preparing to travel to the Congo, Che privately admitted in his Apuntes (published in Cuba over fifty years later with little public impact) that although unions were not required under socialism in order to deal with class exploitation—which didn’t exist, they were necessary to deal with potential abuses in workplaces. Che also admitted in his Apuntes that union democracy in Cuba was a “perfect myth” because the Communist Party proposed the single list of candidates for union office that were always elected but without the involvement of the masses. (María del Carmen Ariet García [editor], Apuntes Críticos a la Economía Política, La Habana, Editorial de Ciencias Sociales, 2006, 412-413.) About what Che Guevara harbored no doubt is that he was opposed to any adversarial relationship between the workers and the employer state, that according to Guevara’s own definition was identical to the working-class vanguard (Apuntes Críticos, 249). In his article of June 18, 1960, “The Working Class and the Industrialization of Cuba,” Che Guevara recognizes that it is not the same thing to be a worker and be the administrator of a factory since the two groups perceive problems from different perspectives. To resolve this problem, Che proposed that the two groups exchange views with each other in order to address the problems from both points of view and thus reach a solution. Essentially, what Che was doing was reducing the problems of class conflict and the hierarchical division of labor to a failure of communication.

When René Dumont, the French left-wing agronomist, tried to convince Che Guevara about the importance of worker participation in their cooperatives in order to create the notion that the cooperatives belonged to them, or to have a sense of their being co-owners of those institutions, Che reacted angrily and proclaimed “that the members don’t need a sense of proprietorship, but a sense of responsibility” (René Dumont, Cuba: Socialism and Development, New York: Grove Press, 1970, 51-52). The government decided that the decision-making power was the exclusive prerogative of the administrators appointed by the central government, a process that was described as collective discussion, but with the responsibility and decisions taken by a single person (Ernesto Che Guevara, “Discusión colectiva: Decisión y responsibilidades únicas,” en Escritos y Discursos, cited in Marifeli Pérez-Stable, The Cuban Revolution, New York: Oxford University Press, 1993, 102).

Ernesto “Che” Guevara and Today’s Cuba

The one-party system has been the principal obstacle to the democratization and progress of Cuba. Che Guevara never criticized, let alone opposed, the one-party state system. The PCC, the single legal party, is not in fact a party: in reality, a party only exists in relation to other parties. But neither is the term “party” useful because it is associated in the minds of millions of people with electoral systems. In the case of Cuba, the Party is far more than an electoral machine because of the transmission belts that it possesses in relation to the so-called mass organizations such as the unions, women’s organizations, and many other institutions including the judicial system, to which the party transmits “orientations” that establish the policies to be followed and implemented in the many different sectors of society. The PCC controls the means of mass communication (radio, television, newspapers, and magazines) through the “orientations” transmitted to such organs by its Ideological Department. We must bear in mind that this department not only censors any domestic news that may harm the government and Cuba’s existing system of government, but also if it is seen by the Cuban government as harming foreign governments that are its allies (e.g., Venezuela and Nicaragua) or with which the government maintains friendly relations (e.g., Lula’s Brazil.) This was also the case decades ago with the Cuban government’s relations with the friendly governments of Francisco Franco’s Spain and of the Mexican PRI. The PCC also controls the Cuban electoral system through the Candidate Commissions as a filter to veto not only opposition candidates, but also those that the Commissions consider likely to ignore the “orientations” of the party in the future. It is the unlimited powers of the PCC spelled out in the Constitution of the Republic of Cuba, that is the principal cause of the pervasiveness of government arbitrariness, that laws are not democratically adopted and in any case are ignored and violated through police and administrative decisions, when the government considers it necessary.

The undemocratic one-party state also allows for the extensive political and social repression in Cuba. According to the British academic institution Institute for Crime and Justice Policy Research that publishes the “World Prison Population List” prepared by Helen Fair and Roy Walmsley, Cuba occupies fifth place in the number of common prisoners per capita (the Cuban government does not recognize the category of political prisoner) among 223 prison systems in independent countries and dependent territories. Cuba is only surpassed by the United States of America, Rwanda, Turkmenistan, and El Salvador. Recently, the number of political prisoners properly speaking rose to many more than 500 because of the trials that took place in connection with the widespread street protests in Cuba on July 11, 2021. The Cuban courts condemned dozens of protesters to many years in prison (including sentences of over twenty years in prison) for damage caused to property. There was not a single case where the demonstrators, who in their great majority were peaceful, caused serious injury or death to any people.

It is necessary to insist that Che Guevara never opposed the one-party system in Cuba or in the USSR, although he did comment on one occasion that the term “democratic centralism” had been used for so many different political systems that it had ceased to have a clear and distinctive meaning. (Guevara, Apuntes Críticos a la Economía Política, 137) It is nevertheless striking that although Guevara harshly criticized the Soviet system, especially regarding the changes that had taken place in its economic structures favoring market forces, and even changed his previously positive opinion of Stalin, at the same time he maintained an uncritical attitude with respect to very important aspects of the Soviet one-party state. Thus, for example, Che Guevara declared “that the Soviet atom bomb was in the hands of the people,” a manifestly false statement that only the uncritical supporters of that political system would have maintained (Apuntes críticos a la Economía Política, 294), aside from the fact that nuclear weapons involved the elimination of entire peoples and cannot distinguish by their very nature between combatants and civilians, and between the ruling classes and the rest of the people.

We must also consider the very serious crisis that Cuba is going through, which approximates in its dimensions the economic disaster that the country suffered immediately after the collapse of the Soviet bloc in the early nineties. Today, Cuba suffers grave shortages of products essential to the feeding and health of the population, with a rate of inflation that reached 45 percent in April 2023, having previously ascended to 77 percent. Consequently, it is not surprising that the value of the dollar has risen a great deal and was quoted as worth 211 pesos (July 13). For a long time, the Cuban economy has been in free fall because the rate of investment has been well below what is needed to maintain the existing standard of living, and even less to support the economic growth required to significantly improve the living conditions of the great popular majorities in the island. The last two years have witnessed the greatest emigration wave — allowed, and indirectly promoted by the government — that Cuba has ever witnessed. It has been calculated that by the end of 2023 more than 450, 000 people will have emigrated in the last two years, an extraordinary number for a country of 11 million people. This emigration will worsen the demographic crisis that Cub has experienced for many years, especially if we consider that it is generally young people that are more likely to emigrate.

Given the very difficult economic circumstances and nature of the Cuban economy, any kind of socialist democracy in Cuba would inevitably have to include a significant private sector composed of small enterprises (although not the so-called “medium” size private enterprises with up to 100 employees allowed by the Cuban government that are really capitalist enterprises) and foreign capitalist investment regulated by the socialist and democratic state. This would require continuing the struggle against the criminal United States blockade that would surely constitute an obstacle to reaching that objective. This would be a new version of what in Russia was called the New Economic Policy (NEP) with concessions to the peasants and small businesspeople and industrialists that Lenin introduced in 1921. The NEP was a consequence of the profound crisis of the policies of War Communism established in 1918. War Communism faced a great deal of resistance from the peasantry (80 percent of the population) as well as armed rebellions, such as the “green” rebellion among the Tambov region peasantry from 1920 to 1921 and that of the sailors and people of Kronstadt in March of 2021.

It is in this context that an extreme voluntarism such as Che Guevara’s would not only not be relevant to today’s Cuba but also politically very harmful. In his analysis of the Russian NEP, Che Guevara ignored the reality of the enormous economic crisis of the Russia of the twenties with the astonishing assertion that in that epoch “there was nothing that was economically impossible” adding that the only thing to be considered was if any economic plan was based on “the development of socialist consciousness” (Guevara, Apuntes Críticos a la Economía Política, 246). In other words, “socialist consciousness” could have conquered the economic obstacles of economic underdevelopment and the great shortages created by the bloody civil war in Russia. In that case, if that “consciousness” had been successful in conquering power, it would have resulted in a brutal and exploitative “primitive accumulation” as in fact occurred under Stalin several years later.

Habel and Löwy accuse me of focusing on the issue of democracy in order to defame Che Guevara and the Cuban revolution. But Guevara’s and Cuba’s consistent opposition to democracy defames the cause of socialism.

Sam is spot on about Guevara, especially Che’s antagonism to trade unionism. I discuss this in my book on Nicaraguan trade unions and another book on authoritarianism in the labor movement. Available here: https://www.amazon.com/stores/Stephen-F.-Diamond/author/B00B9PV2U2?ref=sr_ntt_srch_lnk_1&qid=1635986547&sr=1-1&isDramIntegrated=true&shoppingPortalEnabled=true

A free draft of this paper can be found here: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=1022180