The Adventures of the Communist Manifesto

The Adventures of the Communist Manifesto

Hal Draper

Haymarket Books, 2020, xiv + 352 pp.

One hundred and seventy-two years after its original publication, the Communist Manifesto never seems to go out of style for very long. As the late Marshall Berman once put it,

Whenever there’s trouble, anywhere in the world, the book becomes an item; when things quiet down, the book drops out of sight; when there’s trouble again, the people who forgot remember. When fascist-type regimes seize power, it’s always on the list of books to burn. When people dream of resistance—even if they’re not Communists—it provides music for their dreams.1

With the world facing pandemic, economic crisis, growing inequality, political polarization, and rising international tensions, there is certainly no shortage of troubles, so it may have been the right time for Haymarket Books to republish Hal Draper’s The Adventures of the Communist Manifesto, which includes several versions of Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels’ classic text along with detailed commentary by Draper.

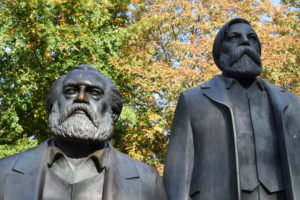

Draper was an active revolutionary socialist in the United States from the 1930s until his death in 1990. He was a prolific writer (a frequent contributor to New Politics in the 1960s and a member of its editorial board), and his multivolume work, Karl Marx’s Theory of Revolution, is still arguably the best study of Marx’s political ideas. Draper was a scholar but never a narrow academic—he wrote for socialist activists who want a deeper understanding of their political tradition precisely so they can respond more effectively to the world’s many troubles. This is definitely the spirit that lies behind The Adventures of the Communist Manifesto.

Full disclosure: I am also the editor of an annotated edition of the Communist Manifesto published by Haymarket Books.2 However, the two editions are not really in competition. Mine was intended for students and young activists new to both Marxism and the Manifesto. Draper’s Adventures, on the other hand, is intended for readers who may already be familiar with the Manifesto but who are interested in taking a deeper dive. It might be particularly helpful for someone who is going to teach a class or lead a study group on the Manifesto or Marxist theory.

Adventures was first published by the Center for Socialist History in 1994, based on an earlier Draper publication—The Annotated Communist Manifesto—and a completed but unpublished manuscript that makes up Part I of the present work. The book consists of three parts in total. First, an extensive history of the Manifesto and its various translations, starting with Marx and Engels’ involvement with the Communist League from 1847, and ending with a survey of English translations produced after 1888. Second, no less than four versions of the text: (i) the original German published in 1848; (ii) the first English translation, produced by Helen MacFarlane in 1850; (iii) the “Authorized English Translation” (AET) produced in 1888 (five years after Marx’s death) by Samuel Moore and extensively reworked by Engels; and (iv) Draper’s own translation (a “New English Version,” NEV) of the text. Third, Draper’s detailed paragraph-by-paragraph annotations.

With respect to the texts of the Manifesto, the MacFarlane version (which renders the pamphlet’s famous opening sentence as “A frightful hobgoblin stalks throughout Europe”) is largely a historical curiosity. The main interest is comparing the AET with Draper’s NEV. As Draper points out, the 1888 translation was based on a draft by Moore that Engels then substantially revised. Engels’ intention was to make the Manifesto more readable and intelligible for an English-speaking audience, and in this he was largely successful. Draper’s new translation is intended to cast light on Engels’ choices and changes. As he puts it, “The considerations that Engels had in mind as he worked hurriedly on the translation should not now continue weighing on all those who come to the Manifesto to inquire into its views. It is necessary to provide a way of getting behind the AET” (106-7).

In a few places, however, Draper also points out that the AET is confusing, misleading, or simply mistaken. As an example of the latter, Draper discovered that an entire sentence was accidentally omitted from the section on “German or True Socialism” in Part III (paragraph 154, p. 173). Another example is a frequently quoted sentence from Part I, in which Marx and Engels credit the bourgeoisie and the economic changes it initiated with rescuing (in the AET’s words) “a considerable part of the population from the idiocy of rural life” (paragraph 28, p. 123). Draper points out in his notes that this is a mistranslation:

The German word Idiotismus did not, and does not, mean “idiocy” (Idiotie); it usually means “idiom,” like its French cognate idiotisme. But here it means neither. In the nineteenth century, German still retained the original Greek meaning of forms based on the word idiotes: a private person, withdrawn from public (communal) concerns, apolitical in the original sense of isolation from the larger community. … What the rural population had to be saved from, then, was the privatized apartness of a life-style isolated from the larger society: the classic stasis of peasant life. (220)

In the NEV, Draper translates this as “the privatized isolation of rural life.”

Even more valuable are Draper’s interpretive comments on the text. In the final sentence of Part I, Marx and Engels declare that the bourgeoisie’s “fall and the victory of the proletariat are equally inevitable” (141). Draper points out, however, that at the beginning of Part I, the authors explicitly say that class struggle may end “in the common ruin of the contending classes” (113). He comments,

Above all, this passage shows how mythical is the view that Marx believed in some sort of metaphysical “inevitably of socialism,” according to which socialist victory is as fatefully predestined as, say, the salvation of Calvinistic saints. … On the contrary, society is faced with the alternatives later tagged “socialism or barbarism”—either a revolution that remakes society or the collapse of the old order to a lower level. … The Manifesto makes clear that the fate of society will be decided as usual by social struggle, not by metaphysics. (210)

But what then of the claim of inevitability at the end of Part I? In the German text, the word used is unvermeidlich,

which often, as in English, conveys nothing more than high hope and confidence in a hortatory context. … In practice the unvermeidlich is counterposed to the accidental, in order to stress that a phenomenon obeys definite laws and is the outcome of causes that can be examined; it implies a scientific attitude to causation, not a metaphysical one. (243)

Draper’s notes contain numerous other valuable insights, including his refutation of the myth that Marx and Engels believed that the middle classes (balanced between the bourgeoisie and the proletariat) would vanish and his commentary on passages where Marx and Engels seem to make incorrect predictions, such as the end of the family (153) or the disappearance of “[n]ational divisions and antagonisms between peoples” (157).

But this new edition would have benefited from some better proofreading. On two title pages at the front, the book is named as “The Adentures of the Communist Manifesto.” Worse, on page 163, the ninth point in the program that Marx and Engels propose at the end of Part II for the “most advanced countries” following a workers’ revolution is missing from the AET translation. (This is the call for “Combination of agriculture with manufacturing industries; gradual abolition of all the distinction between town and country by a more equable distribution of the populace over the country.” In Draper’s translation, this is rendered as a call for “the gradual elimination of the antithesis of town and country,” which seems like a more realistic goal.) No doubt these errors will be corrected in subsequent printings.

Despite these minor blemishes, Draper’s translation and his perceptive and erudite commentaries make this a book that everyone with a serious interest in Marx’s thought will want to have in their collection.

Notes

1. “Unchained Melody,” Nation, May 11, 1998, 11. Reprinted in Adventures in Marxism (New York: Verso, 2001).

2. The Communist Manifesto: A Road Map to History’s Most Important Political Document (Chicago: Haymarket Books, 2005).

Leave a Reply