Four years following its liberation, the predominantly agricultural town of Daraya, strategically located near the capital, has fallen to the regime. A deal was reached to evacuate the 4,000-8,000 civilians remaining from a pre-uprising population of 300,000. The local fighters who defended their town so courageously will go to Idlib and join the resistance there.

Four years following its liberation, the predominantly agricultural town of Daraya, strategically located near the capital, has fallen to the regime. A deal was reached to evacuate the 4,000-8,000 civilians remaining from a pre-uprising population of 300,000. The local fighters who defended their town so courageously will go to Idlib and join the resistance there.

Daraya’s residents know that they may never return to their homes. Photos circulated on social media showed residents gathered at the graves of loved ones to say goodbye. Fears abound of a plan to cleanse opposition strongholds permanently, and in previous evacuation deals, even those carried out under UN auspices, many were detained by the regime, never to be seen again.

But the residents are desperate. A few days ago a group of women from Daraya sent a letter to the world. They described horrific conditions. A regime-imposed siege, ongoing for 1,368 days, had blocked the entry of food and medical supplies. People were starving. They described the daily regime assault which has seen over 9,000 barrel bombs dropped on the town as well as internationally prohibited poisonous gas and napalm. The hospital had been targeted and was out of operation. Agricultural land, the sole source of food, had been deliberately burned and destroyed. The women called on the international community to take action to end the violence and lift the siege. This letter followed months of protests held by women and children with the same demands. The first, and only, aid convoy to reach the town entered in June 2016. It contained medicine, mosquito nets and baby formula, but no food. ‘We can’t take medicine on an empty stomach,’ read a banner at a protest soon after.

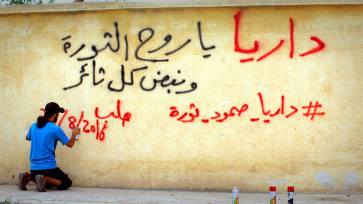

Those who leave Daraya, leave as heroes. Daraya is an iconic town for Syrian revolutionaries. It’s been a centre for the development of the thought and practice of non-violent resistance and has inspired civil disobedience across the country. And despite the horrific repression inflicted on the town, it’s had remarkable success in practicing local, autonomous self organization. Revolutionary activist Razan Zeitouneh, who herself was kidnapped in 2013, said “Daraya was a star before the revolution and a star during. What the young men and women of the city built took immense efforts and resulted in a small exemplary model for the future of Syria, the one we dream of. The activism in the city never ceased to amaze us for a minute… In Daraya, the signs calling for co-existence continued to be held high even when the entire country was falling into despair following every new massacre.”[1]

In 2011, when the uprising began, a local coordination committee quickly emerged to organize anti-regime protests. The committee emphasized the importance of non-violent struggle and handed out leaflets calling for a democratic Syria and for equality between all religious and ethnic groups. As church bells rang in solidarity, protesters marched holding flowers, and handed bottles of water to the security forces sent to shoot them. ‘The army and people are one,’ they chanted. One of those involved with the local coordination committee was a 26 year old tailor called Ghiyath Matar. He earned the nickname ‘Little Ghandi’ for his commitment to peaceful resistance. Ghiyath was arrested by security forces on 6 September 2011. A few days later his mutilated corpse was returned to his family and pregnant wife. In one of his last Facebook posts, Ghiyath said “We chose non-violence not from cowardice or weakness, but out of moral conviction; we don’t want to reach victory by having destroyed the country.”[2]

The principles of non-violent resistance which influenced Daraya’s youth had a history in the town. Unusually for Syria, a police state that ruthlessly suppresses independent organization, a group of young men and women aged between 15 and 25 established the Daraya Youth Group in 1998. They had been studying Quran under the religious scholar Abdul Akram Al Saqqa. Al Saqqa promoted social and political freedom and encouraged free thinking amongst his students. Because of his liberal views he was controversial amongst the Syrian ulema (religious authorities). He called for women to choose their own husbands and argued that women’s education was more important than whether or not they wore the veil. He introduced students to the work of Jawdat Said, an Islamist scholar who promoted non-violent thought and practice through the Quranic traditions as well as the teachings of Ghandi and Martin Luther King. Al Saqqa’s work attracted the attention of the authorities and he was imprisoned in 2003 and 2011. Under his mentorship, the Daraya Youth Group organized actions such as cleaning the streets of their town, boycotting American products, as well as risky campaigns against bribery and corruption. In 2002 they demonstrated against the Israeli invasion of Jenin refugee camp and in 2003 they organized protests(without government permission) against the US invasion of Iraq. This activity led to the arrest of 24 members of the group. A few were soon released but the majority were sentenced to between three and four years in prison. [3]

The peaceful protests were subjected to violent repression. Flowers were met by bullets, protesters were rounded up en masse and detained. In August 2012, following intense shelling, Syrian army troops stormed the town and committed one of the regime’s worst massacres. Some 400 men, women and children lost their lives in execution style killings. Those attempting to flee were hunted down and shot. The bodies of the dead littered the streets or were thrown into mass graves.

In a scene which would be endlessly repeated, some Western commentators sought to exonerate the regime from wrongdoing. The celebrated journalist Robert Fisk visited Daraya shortly after the massacre, embedded with regime troops. He reported that the situation occurred due to Free Army hostage taking and a prisoner exchange gone wrong, quoting sources saying that victims were relatives of government employees. Daraya’s local coordination committee issued a strong condemnation of Fisk’s report. They had never heard of the prisoner exchange story, questioned whether interviewees would be free to speak the truth in the presence of regime soldiers, and criticized Fisk for not meeting with opposition activists. [4]

Daraya was liberated by local rebels three months later. As the state withdrew, residents set up a Local Council to run the town’s affairs. One of those involved was anarchist Omar Aziz who encouraged revolutionary Syrians to organize their communities independently from the Assadist state and work towards advancing a social revolution. Despite enormous challenges, Daraya’s Local Council has had remarkable success. It’s established numerous offices to provide services to civilians including media services, legal services and public relations (they maintain an excellent website). A relief office runs a soup kitchen which began providing three meals a day, although due to the siege frequency was reduced. The council also tried to build self-sufficiency, growing beans, spinach and wheat. A medical office supervises the field hospital which provides for the sick and wounded. A services office is responsible for opening alternative roads when the main ones are inaccessible due to airstrikes or collapsed buildings. The local council also aimed to unify civil and military efforts. Daraya is one of the few communities where the local Free Army brigade is part of the council’s organizational structure and subject to civil administrative control. Revolutionary women set up the Enab Baladi magazine to discuss events happening in their community and Syria more broadly and promote civil disobedience. Activists built an underground library so residents could continue their education.

The people of Daraya have paid a heavy price for their dream of freedom. For four years they defended their autonomy from the Assadist state and kept going despite the bombing, despite the starvation siege. Their struggle will continue to be remembered and honoured by Syrian revolutionaries everywhere.

Notes:

- Cited in ‘Daraya: the town that shames the world’, The Syria Campaign, March 2016.

- Cited in Mohja Kahf, ‘Water bottles & roses: Choosing non-violence in Daraya’, 21 November 2011.

- For more information see Mohja Kahf, ‘Water bottles & roses: Choosing non-violence in Daraya’, 21 November 2011.

- The American war reporter Janine Di Giovani also entered Daraya (without the regime) a few days after the massacre. She gives a harrowing account in her excellent book The morning they came for us (Bloomsbury Publishing, 2016).

Originally posted here.

Leave a Reply