Yes, the PMC Exists: A Reply to David Camfield

In a recent New Politics essay David Camfield argues that the “PMC” (shorthand for “professional-managerial class”) does not exist and that belief in it hinders socialist organizing. He presents a simplified, partly inaccurate version of the concept and rehearses an age-old critique: that different social functions ≠ different social classes. The upshot of his argument is that ‘we are all workers’ except “middle managers” and actual capitalists as well as (presumably) the petit bourgeoisie. While admirable and even correct in its activist thrust—yes, both workers and professional-managers share a common antagonism with capital and no, teachers, journalists and tech workers should not feel guilty about organizing, striking or advancing their interests collectively—Camfield’s argument is wrong in its theoretical understanding of class. His attempt to define away the structural domination of most workers in their day-to-day lives by professionals and managers is also potentially harmful: it obviates the need to address this inequality head-on in activist circles and try to overcome it through practice. Here I’d like to provide two counterpoints: 1) the PMC does exist, and 2) acknowledging this does not have to paralyze organizing but can actually empower workers within cross-class movements—including, and especially, those for socialism.

In a recent New Politics essay David Camfield argues that the “PMC” (shorthand for “professional-managerial class”) does not exist and that belief in it hinders socialist organizing. He presents a simplified, partly inaccurate version of the concept and rehearses an age-old critique: that different social functions ≠ different social classes. The upshot of his argument is that ‘we are all workers’ except “middle managers” and actual capitalists as well as (presumably) the petit bourgeoisie. While admirable and even correct in its activist thrust—yes, both workers and professional-managers share a common antagonism with capital and no, teachers, journalists and tech workers should not feel guilty about organizing, striking or advancing their interests collectively—Camfield’s argument is wrong in its theoretical understanding of class. His attempt to define away the structural domination of most workers in their day-to-day lives by professionals and managers is also potentially harmful: it obviates the need to address this inequality head-on in activist circles and try to overcome it through practice. Here I’d like to provide two counterpoints: 1) the PMC does exist, and 2) acknowledging this does not have to paralyze organizing but can actually empower workers within cross-class movements—including, and especially, those for socialism.

Camfield correctly attributes the PMC concept to Barbara and John Ehrenreich’s influential 1977 article. He also correctly reproduces their basic definition of the group as “salaried mental workers” who “reproduc[e] capitalist society” through their various occupations as “teachers, social workers, psychologists, entertainers, [and] writers of advertising copy and TV scripts,” among many others. What he fails to provide is even a short recap of the Ehrenreichs’ structural explanation of this group’s formation and role, which is indeed part and parcel of their designation as a class. Camfield’s inaccurate focus on “status,” “skill” and “autonomy” as allegedly defining features of PMC membership is also strange, along with his simple assertion—via Ellen Meiksins Wood—that there are only two mutually exclusive ways to define class: “either as a structural location or as a social relation” (as if one’s role in a social relation does not simultaneously place one in a socio-structural location vis-à-vis other actors). Let’s consider these deficits, starting with definitions.

The Ehrenreichs’ full definition of the PMC is as follows:

“salaried mental workers who do not own the means of production and whose major function in the social division of labor may be described broadly as the reproduction of capitalist culture and capitalist class relations. Their role in the process of reproduction may be more or less explicit, as with workers who are directly concerned with social control or with the production and propagation of ideology…Or it may be hidden within the process of production, as is the case with mid-level administrators and managers, engineers and other technical workers whose functions…are essentially determined by the need to preserve capitalist relations of production.”

They frame this not as a scholastic definition valid across space and time, but as a functional role produced for a group through more than a century of capitalist development and class struggle. Specifically, they cite the rise of “monopoly capital” (or what we might term ‘big-firm’ capital since actual monopolies are in no sense intrinsic), the deskilling of labor in production, a series of pitched battles between workers and employers and the massive expansion of state functions aimed at shoring up social reproduction and ‘order’. These combined processes, which are clearly demonstrable in the U.S. from the late nineteenth century to the Second World War, accomplished two things, according to the Ehrenreichs. On the one hand, big firms with increased productivity and the explosive character of working-class resistance convinced large sections of capital that investing in a permanent corps of administrators, officials and experts was both possible and necessary. On the other hand, deskilling on the shop floor and state intervention into education, childrearing and medicine as well as expansion of repression (police, prisons, courts) served to extract skills and practice from working class members and re-assign them to designated experts and officials—engineers, teachers, doctors, cops—who were then placed in positions of authority over them. “It is simultaneously with these developments in working-class life,” the Ehrenreichs argue, or “(more precisely, in the relation between the working class and the capitalist class) that the professional and managerial workers emerge as a new class in society” (16).

This is class as a social relation, but a double relation. The PMC is dependent on capital for their share of the surplus (paid as salary) and tasked with fulfilling capital’s needs for profitability and social quiescence. A latent conflict exists between them and capital over the share of surplus paid out and the degree of autonomy granted PMC members to perform their jobs. Yet their jobs do not involve, in the vast majority of cases, producing commodified use values but either directly (e.g. supervisors, police officers, social workers) or indirectly (e.g. engineers, programmers, advertisers) steering the behavior of working class people who often experience PMC directives, “suggestions,” blueprints and algorithms as forms of domination, however benevolent. Hence a double social relation—one with capital, another with workers—and thus a socio-structural location between labor and capital.

Whether or not one accepts it, this is at least a more complete picture of the Ehrenreichs’ concept than the strawman Camfield provides. Status, autonomy and skill are nowhere constitutive of PMC membership except insofar as they are deployed to dominate, direct or supervise others, typically members of the working class. None of this, however, answers the theoretical question of “class”.

Class is a socially defined relationship to the means of production. This can take the form of juridical property (or lack thereof) but need not in every case, as the wide variation in legal forms of ownership and actual productive practice throughout history attest. What is decisive is whether a group plays a distinctive role in production vis-à-vis other groups involved in the same collective process. To simplify, we can say that juridical property furnishes three largely uncontroversial class groups in developed capitalism: 1) capitalists who reap profits from large shares of productive property that employ many wage workers; 2) workers who don’t own such shares and must sell their labor power for a wage; and 3) petit bourgeois who own small shares of productive property, employ few or no workers and often engage in the productive process itself. The problem, however, is that the second category is so universal that it conceals more than it reveals. While only 1-2 percent of the economically active population of the U.S. are capitalists and 9-10 percent are self-employed (largely coterminous with the petit bourgeois), nearly 90 percent are “wage and salary workers”. This includes architects, doctors and corporate PR directors alongside retail salespersons, construction laborers and home health aides. More to the point, if left undifferentiated, this class category would include frontline, value-producing workers alongside top-level managers and professionals whose plans and directives they work under and who have great sway over their livelihoods.

Though one could dig in and assert that this is just a very big, internally-divided class, most don’t, including David Camfield. Though each draws boundaries somewhat differently, writers as diverse as C. Wright Mills (1951), Nicos Poulantzas (1975), Harry Braverman (1974), Erik Olin Wright (1986, 1997), Michael Zweig (2000) and Erikson and Goldthorpe (1992) all place groups largely identical to the Ehrenreichs’ PMC outside the working class. Wright and Mills define their ‘middles’ as largely non-agentic ‘no-man’s lands’ between true classes; Goldthorpe sees one “pole” of administrative and professional “employees” counterpoised to “unskilled manual and entirely routine grades of nonmanual” employees, as well as to employers and the self-employed; while Poulantzas and Zweig group most professional-managers in one class with the petit bourgeoisie (though with different political conclusions).

Kim Moody, founding member of the socialist organization Solidarity, Labor Notes and advocate of bottom-up, militant unionism as a pathway to socialism, makes much the same distinction between PMC and working class that the Ehrenreichs propose. In his most recent survey of U.S. labor, On New Terrain (2017), he places “managerial” and “professional” employees in a “middle class” separate from the working class (p. 40). He categorizes 23 percent of this middle—including teachers and registered nurses—in a “proletarianizing” sub-tier, due to the declining real power they have over clients and other employees in the face of tightening capital-state pressure and routinization. But he still places them outside the working class and even uses Camfield’s (via Wood’s) forbidden language of ‘location’: “‘Middle class’ refers not to those statistically in the middle-income range…but those socially located between capital and the working class in the production of society’s wealth” (ibid; emphasis added).

Even Camfield explicitly excludes one segment of employees—“middle managers”—from the working class. But given his insistence that “the PMC does not exist” it is unclear where or in what social relationship he situates this group and on what criteria he excludes them from the working class. Are they capitalists? Maybe, but this would bend any straightforward understanding of the term since “middle managers” typically don’t own the companies they work for or the divisions they manage, aren’t paid dividends, are employed at the discretion of top managers and shareholders, etc. Should they be grouped with the petit bourgeois? Again, since they don’t own and control their own independent small capital this match is equally ill-fitting. So on what basis does Camfield justify excluding only “middle managers” from the larger group of working-class employees? We don’t know, because he doesn’t elaborate. If he were to make this justification in the plausible direction of power relations this would immediately beg the question as to why only middle managers and not lower or frontline managers—who also have institutional authority over employees—are separated out. If institutionalized power were the question—and again we don’t know if it is—why are only middle managers and not police officers, detectives or criminal court judges separated out, since these groups have ostensibly even greater power over citizens and defendants, the bulk of whom are working class?

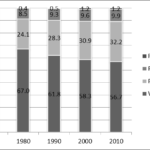

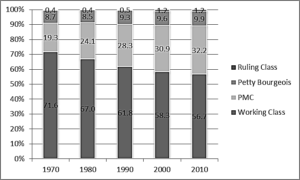

Following the power criterion to its logical conclusion would likely result in separating out from the working class proper a group of professional and managerial employees that looks remarkably similar to the Ehrenreichs’ PMC. Indeed, this is what I and a colleague did in order to chart the growth and decline of U.S. classes from 1970 to 2010 (Ikeler and Limonic 2018). Using Census data and the active workforce as our universe, we found petit-bourgeois stasis over the period (around 9 percent), PMC growth (from 19 to 32 percent), working class decline (from 72 to 57 percent—still the clear majority), and ruling class growth (from 0.4 to 1.2 percent) (Figure 1). More dramatic, though by no mean constitutive of class difference by Marxist standards, was the persistent and growing income gap between the working class and the PMC. Since at least 1980, average PMC members consistently earn double or more than average working-class members, and this only includes the actively employed shares of either class (Figure 2).

Figure 1: Class Percentages of U.S. Active Workforce, 1970-2010

Figure 2: Median Annual Earnings (2010 $) for U.S. Classes, 1970-2010

So what does it mean in practical terms if we accept “PMC theory”? Does it “get in the way of understanding and participating in the struggles of…the working class,” as Camfield argues? Does it pose an insurmountable “obstacle” to PMC members’ “unionizing, striking, and finding common cause with…the working class?” Does it “encourage guilty moralism…among university-educated” employees? Aside from the logical error Camfield is making here—that an objective concept should be ditched because of its uncomfortable practical implications—he also overgeneralizes. The answer to each of these questions is no.

Assignment or belief in oneself or someone else as part of a class with systematically defined relationships with other classes is not a moral judgment. To say architects have authority over estimators and laborers, to say teachers have the same over paraprofessionals and students, to say fashion designers have remote but real authority over garment producers—or to recognize one’s own institutional authority in any of the first three occupations—is not to say “bad” architect, “bad” teacher, or “bad” designer. It is simply to acknowledge the very real—even if beneficial or benevolent—power asymmetries between such groups.

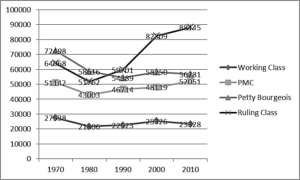

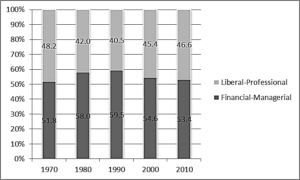

Both the working class and the PMC have beef with capital: the former vis-à-vis surplus extraction and state repression, the latter vis-à-vis salary, autonomy and ability to serve the long-term interests of their clients. Teachers in Chicago, West Virginia and L.A., while acknowledging their relative empowerment over working-class students and communities, have fought militant successful strikes in recent years for those students’ interests, as well as their own. Registered nurses in Illinois, California, Arizona, Florida and New York struck or almost struck in 2019, primarily over staffing levels to ensure patient care and safety. And engineers and programmers at Google have been organizing proto-unions—and some of them fired because of it—that simultaneously fight sex discrimination and the pursuit of ICE contracts by their employer. In all of these cases, PMC members are using historically working-class methods of struggle to fight for both their interests and those of worker-clients. In a more nefarious example, many police unions mobilized against greater oversight of their members’ use of lethal force in the wake of Black Lives Matter protests. Here, one group of PMC members used working-class-type organizations to press their interests over and against those of mostly working-class constituents. The point is that the PMC itself is divided between those tasked with developing human and productive forces, what we call the “liberal-professional” segment, and those tasked with maintaining accumulation and social order, what we call the “financial-managerial” segment (Figure 3). It is with the former that working-class interests are more often aligned, though by no means identical.

Figure 3: U.S. PMC Segment Percentages, 1970-2010

Classes are of course fuzzy at their boundaries and the PMC is no exception. Is a college student on track to become a professional or manager but currently working retail in the PMC or the working class? Is the upper-level manager who’s paid increasingly out of profitability bonuses in the PMC or the capitalist class? Is the construction worker who starts a side business repairing rooves a worker or petit-bourgeois? Is the daycare director who used to teach classes but no longer does and now administers a growing cadre of employees petit bourgeois or capitalist? These are Sorites paradoxes not exclusive to the PMC. The fuzziness is the same in each case. The point is that classes are not micro-level concepts designed to sort each and every individual; they are socio-structural concepts designed to explain the internal tensions, interest configurations and long-term development of large human groupings (“societies,” “social formations,” “modes of production”). And none of this even touches on the more anthropological or culturalist conceptions of class, namely as bounded intergenerational groupings that pass on not only property and productive roles but also distinctive habits, practices, worldviews, etc. Suffice it to say there is plenty of evidence on this front as well of meaningful differences between working class and PMC patterns of social and ideological reproduction (Lareau 2003; Jensen 2012; Streib 2014; Cherlin 2014; Willis 1977).

Aside from its objective validity, the practical utility of the PMC concept is its ability to shed light on oft-unspoken divisions within social movements and organizations. For those of us involved in such efforts, how often have we seen leaders, strategizers and thinkers drawn from or self-selected from participants who hold professional or managerial jobs? Without denigrating any of their contributions, we should also ask ourselves—and not just in passing—to what extent these patterns recreate for working-class participants the same dynamics of inequality they experience in late-capitalist workplaces and society? We (the left) regularly ask ourselves these questions vis-à-vis race, gender and sexuality—and rightly attempt to correct them within our organizations and movements, with varying degrees of success. Why shouldn’t we do the same for internal class or semi-class divisions?

Clearly there are bigger objectives for the 21st-century left than sorting out our own internal hang-ups, and none of this is to suggest that PMC/working-class divisions are ‘the’ issue we need to deal with before all else. But they are an issue that has been known to creep into and distort left organizing in the past. Acknowledging and understanding such divisions are first steps toward overcoming them in practice which could help today’s left avoid key snags encountered by our mid-twentieth-century predecessors. Denying the class-based reality of such divisions, as Camfield would have us do, forecloses this development.

References

Braverman, Harry. 1974. Labor and Monopoly Capital: The Degradation of Work in the Twentieth Century. New York: Monthly Review Press.

Cherlin, Andrew J. 2014. Labor’s Love Lost: The Rise and Fall of the Working-Class Family in America. New York: Russell Sage.

Ehrenreich, Barbara and John Ehrenreich. 1979. “The Professional-Managerial Class.” Pp. 5-45 in Walker, Pat (ed), Between Labor and Capital, Boston, MA: South End Press.

Erikson, Robert and John H. Goldthorpe. 1992. The Constant Flux: A Study of Class Mobility in Industrial Societies. New York: Oxford University Press.

Ikeler, Peter and Laura Limonic. 2018. “Middle Class Decline? The Growth of Professional- Managers in the Neoliberal Era.” The Sociological Review 59(4): 549-570.

Jensen, Barbara. 2012. Reading Classes: On Culture and Classism in America. Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

Lareau, Annette. 2003. Unequal Childhoods: Class, Race, and Family Life. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Mills, C. Wright. 1951. White Collar: The American Middle Classes. New York: Oxford University Press.

Moody, Kim. 2017. On New Terrain: How Capital Is Reshaping the Battleground of Class War. Chicago: Haymarket Books.

Poulantzas, Nicos. 1975. Classes in Contemporary Capitalism. London: New Left Books.

Streib, Jessi. 2014. The Power of the Past: Understanding Cross-Class Marriages. New York: Oxford University Press.

Willis, Paul. 1977. Learning to Labour: How Working Class Kids Get Working Class Jobs. New York: Columbia University Press.

Wright, Erik Olin. 1986. Classes. New York: Verso Books.

Wright, Erik Olin. 1997. Class Counts, Student Edition. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Zweig, Michael. 2000. The Working Class Majority: America’s Best Kept Secret. Ithaca: ILR/Cornell University Press.