White Supremacy and its Allies

Perhaps the difficulty in capturing and defining the phenomenon of white supremacy lays in its ubiquity. Throughout American society (and more generally, across the Western world), ‘whiteness,’ symbolizes a status quo, a dominant set of norms and behaviors to which individuals are expected to adhere.

Of course, ‘whiteness’ itself is a concept that has been remarkably dynamic and elastic throughout American history; initially rooted in a particular subset of Anglo-Saxon Protestant identities, the term has gradually grown more and more capacious over the last two and a half centuries to accommodate virtually anything ‘familiar’ to the Western world. White supremacy may be understood as a set of power relations, encoded within systems, institutions, and norms, intent on maintaining the hegemonic power of whiteness. When the currency of whiteness – of normalcy – is threatened, white supremacy is our nation’s instinctive counterweight to restore equilibrium.

Chattel slavery and Jim Crow embodied evolving iterations of an enduring systematic oppression, one that began as a form of economic exploitation, but ultimately enabled an order that came to dominate the political, social, and cultural spheres of Black life. It’s this order that white supremacy seeks to maintain, and its maintenance rarely requires any disruption; on the contrary, it relies on inaction, complicity with the inertia of any existing power relations. The machinations of white supremacy, which animated and inaugurated our Republic, have had clear and lasting material effects across racial, class, and gender lines.

How is the United States to reconcile with its guiding principle of white supremacy, which has subjugated millions of people over three hundred years? The question remains urgent as ever today, and while I can’t hope to give any comprehensively conclusive answers, I hope to shed light on how we may begin to understand some of its dimensions.

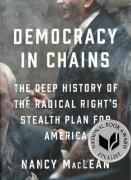

On its surface, the utility of Nancy MacLean’s Democracy in Chains: The Deep History of the Radical Right’s Stealth Plan for America in conceiving of white supremacy may not be apparent. It’s certainly is a welcome addition to the burgeoning canon of literature aimed at demystifying the American right-wing machine, a machine that has colored political discourse and policy priorities for much of the past three decades (Jane Mayer’s Dark Money: The Hidden History of the Billionaires Behind the Rise of the Radical Right first emerged as the standard-bearer of this topic). Under the auspices of ‘protecting individual liberty,’ a handful of corporate donors have been funneling billions of dollars into political and social institutions: political action committees, universities, think thanks, and philanthropies have been the primary targets of this deluge.

MacLean focuses on James M. Buchanan, who was considered a relatively obscure economist (outside of the academy and right-wing circles) prior to the publication of Democracy in Chains. Academically, he’s best known as the founder of the Virginia school of political economy, which gave way to the economic discipline of Public Choice Theory: he would ultimately win the Nobel Prize in Economics in 1986 for his contributions to the field. Buchanan spent much of his teaching career in Virginia, specifically at the University of Virginia, Virginia Tech, and George Mason University. He found kindred-minded economic and social theorists through his involvement with the Mont Pelerin Society, the influential classical liberal organization based out of Switzerland – through the MPS, he befriended figures such as Friedrich Hayek, Milton Friedman, and Ludwig von Mises.

A crucial element of MacLean’s narrative considers Buchanan’s involvement in Virginia’s desegregation debate of the late 1950s. The ruling of Brown v. Board of Education in 1954 ruled that schools across the American South must be integrated – Virginia effectively delayed the implementation of integration for two years through legal challenges, but by 1957, state legislators were running out of options. With the potential of federal intervention looming, Senator Harry Byrd’s segregationist political machine scrambled to plot its next move –Virginia’s power brokers hoped to avoid the national embarrassment wrought if President Eisenhower mobilized the National Guard, as he did in Little Rock. However, they still remained uncompromising in their commitment to segregation. The resulting course of events rivals Little Rock in infamy: in a period that became known as “Massive Resistance,” schools across Virginia closed in protest of integration beginning in 1956. The entire ordeal would last several years, and it prevented thousands of children, both black and white, of a public education. Today, it’s regarded as a shameful chapter of Virginia history, though it remains the subject of fascinating study.

Momentum for Massive Resistance waned considerably following Norfolk’s decision to reopen its schools in early 1959 – one of Virginia’s larger population centers, Norfolk’s closures deprived nearly ten thousand white students of an education. Its capitulation indicated the imminence of integration, as well as the declining power of the Byrd machine. In February 1959, Buchanan and Warren Nutter, a fellow Virginia School economist, circulated a report entitled “The Economics of Universal Education” to the members of a newly formed commission of legislators tasked with resolving the schooling crisis.

The report, which was later published in the Richmond Times-Dispatch, argued that court-ordered integration would not be the ideal action to end Massive Resistance. It fundamentally took issue with the idea that the federal government could carry such a far-reaching edict, coercing individuals into integration and thereby violating their freedom of association. Instead, it argued that a preferable course of action would be a massive privatization of public schools via the institution of a voucher system – recognizing the steep cost to such an endeavor, they argue for it to be financed (at least in part) by the private bidding of public school infrastructures, such as school buildings and supplies. Above all, the state ought not carry a monopoly on education; more widespread competition would facilitate better education outcomes for both black and white students.

By today’s standards, Buchanan and Nutter’s report could hardly be deemed ‘radical,’ though this alone is a powerful testament to the normalization of libertarian right’s agenda. They frame their report in purely economic terms, avoiding any normative prescriptions rooted in social, cultural, or historical contexts. It reads quite innocuously, rife with disclaimers that the report contributes just one aspect of a contentious debate, and that ultimately, the commission must consider more than just economics. They never explicitly condone the segregationists’ agenda, though racist parents and policymakers had long called for privatization, as ‘school choice’ provided a thinly veiled means to reproduce de-facto segregation. Their goal was to contribute an economic analysis of the situation, and then, in their words, “[let] the chips fall where they may.”

While the report made no meaningful impact on Massive Resistance, it did signify the first major output of Buchanan’s Department of Economics at the University of Virginia. MacLean’s focus on this intervention has spurred an important question about how we ought to interpret the economist’s legacy: what wrongdoing, if any, should we attribute to Buchanan?

Before getting to this specific question, it’s worth contextualizing the reception of Democracy in Chains. Since its release last June, the book has been the target of extreme censure from the libertarian right: dozens of critical reviews have been published across an array of outlets. It’s unsurprising that the vast majority of them come from scholars affiliated with the Koch network – in an interview with journalist Daniel Denvir from early June 2018, MacLean counts 101 critical engagements with her book, about 91 of which came directly from “Koch-subsidized professors or operatives in Koch-funded institutions.”

Libertarian critics have attempted to methodically pick apart virtually every element of MacLean’s book (the Left ought to learn a lesson in movement cohesion and unity from the libertarians’ coordinated assault). Some of the reviews address, concerns with MacLean’s scholarship that are beyond my scope of expertise: for example, her deployment of misleading quotations, shoddy history, and reductive descriptions of public choice theory. Many criticize MacLean’s (at times) gratingly histrionic prose in the introduction; others argue that the contents of the introduction, coupled with inaccuracies, make Democracy in Chains “a work of speculative historical fiction.” While the breadth of criticisms is quite remarkable, I’m going to focus on two recurring themes that surface in most engagements from the libertarian right: Buchanan was not a racist, and Buchanan’s political philosophy was not anti-democratic, but instead sought to protect against majoritarian rule. These lines of inquiry are quite illuminating and instructive in our task of unpacking white supremacy.

With this context, let us return to the question previously posed: what are we to make of Buchanan’s role in Massive Resistance?

For MacLean, this episode reveals Buchanan to be a nefarious actor, one who knowingly capitalized on widespread racism to pursue his own ideological ends. She never accuses Buchanan of personal racial animus, but indicts him on what is perhaps a more pernicious charge: mortgaging the well being of Black children (who would’ve undoubtedly suffered under his proposed plan) purely for the sake of an ideological victory. In MacLean’s view, he must have understood the implications of his plan: that is, he knew the segregationists would latch onto it in hopes of furthering their own racist goals.

This chapter of Buchanan’s life has emerged as somewhat of a contentious battleground in determining the economist’s legacy, as my proceeding survey of the libertarian intelligentsia will indicate. In less diplomatic terms, the resulting discourse on the libertarian side has been nothing short of a shrill cacophony of Koch-funded scholars, metaphorically tripping over themselves to rescue their darling Buchanan from the dreaded moniker of ‘racist.’

Let’s start with Michael Munger, who writes, “Buchanan was not a racist. He did not favor the disenfranchisement of groups, and he was very much worried about the use of military and police power to repress citizen voices.” (It’s worth noting that the second clause is a comically ironic characterization, given Buchanan’s enthusiastic support for the police repression against the UCLA students who were protesting Angela Davis’ dismissal in 1969.)

Many critical reviews I’ve encountered, especially from Public Choice academics, regurgitate this refrain: Buchanan was a good man, devoid of any racist sympathies. Take another one from Phillip Magness, who essentially argues that Buchanan couldn’t have been racist, since he invited William H. Hutt, a South African free-market scholar and anti-apartheid activist, to the University of Virginia in 1965.

Henry Ferrell and Steven Teles consider Buchanan’s relationship with Hutt as well, writing that the Hutt hire “does not exonerate Buchanan, as some of MacLean’s critics imply, but it does suggest that his opportunism might have been undiscriminating in its willingness to cater both to strong supporters and genuine critics of racism—as long as both built on his ideas about liberty and public choice.”

Their analysis falsely equates Buchanan’s invitation of a single scholar critical of apartheid, and his decision to propagate a system that would disproportionately harm thousands of black children. Perhaps an example of a truly ‘undiscriminating’ application of his ideas would be if he’d written about the need to expand the franchise black Americans – however, as we know, many libertarians, of Buchanan’s era, as well as today’s era, lament any political empowerment to the marginalized (we’ll get to that later).

D.W. MacKenzie’s take rivals Magness’s in terms of absurdity – he simply recounts a graduate seminar taught by Buchanan in 1999, wherein Buchanan taught how the assumption of ‘minority avoidance’ can lead to ‘full-blown racial segregation,’ and so, he must have possessed some consciousness about race.

In one part of Brian Doherty’s lengthy review, he ponders the motivation for Buchanan’s actions:

Was Buchanan happy to see black students get no formal schooling? Or did he think—in line with his overarching belief that free markets would tend to meet most human needs, especially with demand financed by state tuition grants—that black children would ultimately get better service as paying customers of new private schools than as a class considered a contemptible nuisance in the old public ones? Or did he not consider the question at all? The documentary record that I’ve seen doesn’t settle this issue.

Let us consider each of the three questions that Doherty presents. The implications of the first question, which posits Buchanan was actively happy that Black students could not access schooling, need little explication – if this was the case, he’s clearly guilty of both overt racist attitudes and perpetuating systemic racism. The third question, which posits that he didn’t consider the results of his actions toward Black schoolchildren, is not much better – the only difference here is that active racial animus did not a role in his decision-making.

The second question, which posits that Buchanan sincerely believed private schools would facilitate the best outcomes for Black children, seems to be the most plausible scenario for Doherty. It suggests that Buchanan was genuinely invested in the welfare of Black children and their right to education, and sought to pursue these ends in his own heterodox fashion. However, given the political circumstance of the time, and Buchanan’s corresponding actions, this line of argument is truly bewildering. To endorse privatization in the Massive Resistance moment would mean knowingly siding with white supremacist segregationists. If Buchanan were to maintain such a commitment to the welfare of Black children, he would’ve had to be painfully ignorant, or downright stupid. Even Farrell and Teles concede that such naivety would be implausible, writing “the most credulous political naif would have understood what the implications of privatization were likely to be in the context of vicious white opposition to school integration.” Of course, this doesn’t necessarily denote racial animus on Buchanan’s part; but to suggest that he seriously sought to advocate for Black children’s education, in light of his actions, is laughable.

Georg Vanberg writes of two private letters he recently discovered, written by Buchanan in 1984, in which Buchanan describes his apprehensions with certain aspects of vouchers – in one, he warns against an unregulated voucher system “to avoid the evils of race-class-cultural segregation that [it] might introduce,” while in another, he demonstrates his ideological restraint, saying “if truth were known […] I am less of an opponent of state schools than many of our friends, at least in principle.” Vanberg considers these letters amidst the greater framework of Democracy in Chains, and he employs them as conclusive evidence to exonerate Buchanan from any charges of racism:

The central rhetorical strategy of Professor MacLean’s book is the insinuation that Buchanan (and others working in the public choice tradition) were motivated by racial animus, and a desire to maintain the dominant position of a privileged, white, male elite. According to MacLean, this led them to develop a particular approach to thinking about politics, and to advocate for institutional and constitutional rules that, according to Professor MacLean, institutionalize (among other ills) racist practices. Buchanan’s letters to Seldon directly contradict this unsubstantiated characterization of Buchanan’s motivations and view.

This is a particularly interesting engagement, as Vanberg appears to grasp certain aspects of MacLean’s project better than most of his peers – still, it imposes a motivation of racial animus into the narrative of Democracy in Chains, which is incorrect, and suggests a fundamental misunderstanding of her project.

Unbeknownst to them, many libertarians who critically engaged with MacLean’s work actually agree with her on a crucial premise: Buchanan’s actions aren’t rooted in predetermined, racist prejudices. For MacLean, they’re rooted in his fixation on ideological purity and the maintenance of the existing power structure. This is a point worth reiterating: MacLean never once alleges Buchanan is a racist, and the fixation of libertarian critics to save him from this nonexistent charge perfectly illustrates how many in the libertarian intellectual movement don’t grasp crucial tenants of white supremacy and antiracist thought.

I suppose it’s nice to learn that Buchanan was willing to host an anti-apartheid activist in the midst of the Civil Rights Movement, or that he taught the ills of total racial segregation in a graduate seminar in 1999, or that in 1984, he furtively cautioned against the complete evisceration of public education. But for myself, and many others, Buchanan’s private attitudes are of significantly less concern compared to his actual work and advocacy. I’d even venture to say that most people who are seriously invested in racial justice would be patently unconcerned with his personal views.

To MacLean, the issue with Buchanan doesn’t reside solely in the sphere of personal motivations: the above engagements, which seek to correct this narrative, are of little use to us. At a foundational level, racist attitudes certainly perpetuate mechanisms of white supremacy; they can’t be divorced from the institutions they inform. But on an individual level, liability for racism is often tangled in a web of extenuating factors and contextual circumstances (granted this is a moderate, conciliatory position, and not one that I entirely agree with – still, I’ll operate under these assumptions for the purposes of this argument).

What we can concretely assess, however, are the ways in which individual actors capitalized on, and in this case actively weaponized, such attitudes. There is a degree of responsibility in passively perpetuating white supremacy, whether it’s in the arena of individual attitudes or systems. However, we should assign a significantly higher degree of responsibility for those whose actions actively furthered the systems of white supremacy – past the muddled matrix of individual responsibility, the real-world consequences of actions endows this paradigm with greater importance. Put another way, the quietly racist man who never brandishes his hatred outward affects less harm than the racially apathetic man who allies with white supremacists to further his agenda.

While racist attitudes are worth deconstructing and challenging, any analysis must involve the larger context of systems. I don’t intend to pose attitudes and systems as unrelated paradigms (they probably shouldn’t be separated at all) – they’re symbiotic, constantly looping into and enabling each other. This framework enables a clearer appraisal of Buchanan’s actions: sure, we can scour correspondences for bigoted remarks, or inquire about anecdotes of personal racism, but this can’t account for the consequences of the decisions Buchanan made to court white supremacists.

For further evidence of this claim, we can consider Buchanan’s relationship with the staunchly white supremacist Byrd Machine – MacLean demonstrates that Buchanan’s totalitarian control of the UVA Economics Department was, in large part, due to the support he received from segregationist legislators. And as the influence of the Byrd Machine atrophied following the collapse of Massive Resistance, Buchanan found his status at UVA threatened. Ultimately, Buchanan would be forced out in 1968, as he’d lost the political capital he’d spent the past decade accruing – many of the segregationist legislators he befriended lost their seats in a post-Massive Resistance wave election. His relationship with the legislator C. Harrison Mann, who authored five bills in the Virginia state legislature against the NAACP, is worth noting as well. Mann corresponded with Buchanan, encouraging him to publish the report in 1959.

Of course, critics of MacLean will quickly dismiss this entire episode as a non-issue. Those on the Right are willing to confer every last measure of reasonable doubt to those that demonstrate racist sympathies – anything short of Klan hoods and burning crosses resists the characterization of ‘white supremacist.’ Libertarians are especially tone-deaf on issues related to race, as we’ve seen. The movement’s membership is blindingly white: an average across nine self-surveys between 2012-2014 demonstrates that over 70% of those who identify as libertarian are white (the source can be found linked here, to a news article which is ludicrously titled “Libertarians Are More Racially Diverse Than Some May Realize”); another survey, conducted in 2013 by the unaffiliated Public Religion Research Institute found that 94% of libertarians are non-Hispanic whites. I’m no expert in social science and can’t speak to the veracity of either set of data, but at the very least, we can formulate an image of libertarianism as an intellectual and political movement dominated by racial uniformity.

This massive blind spot reveals itself again, in the libertarians’ engagement with MacLean’s critique of Buchanan as antidemocratic. In another piece examining Democracy in Chains, Georg Vandeberg writes:

Buchanan’s careful analysis, originating in his seminal work with Gordon Tullock, “The Calculus of Consent,” led him to the conclusion that in choosing a political framework (“constitution”), all individuals will typically have good reasons to favor some restrictions on majority rule in order to protect against the “tyranny of the majority.” […] In other words, what justifies ‘chains on democracy’ for Buchanan are his commitment to individual autonomy and equality, and his emphasis on consent as a legitimating principle for political arrangements.

Michael Munger expounds on this sentiment:

[MacLean] is incensed by the argument that real democracy requires majorities to be shackled (as her title suggests) “in chains.” Of course it does. That is one of the core premises of liberalism, that the rights of minorities must be protected. In fact, we all agree (there may be some exceptions, but I’m not aware of many serious ones) that majorities must be limited: even if the white majority wants to maintain an apartheid system of schools and public accommodations, they must be prevented from doing so…

Buchanan’s argument was simply that democracy must balance the rights of individuals and the power of majorities. Democracy must, in this sense, be limited. Where the limit should be placed is a perfectly legitimate object of academic discussion. But the fact that there should be a limit is a core premise of liberalism. Why does MacLean pretend that limiting majority rule is controversial, or that anyone who would advocate limits on majorities opposes the Constitution? The Constitution itself—as Buchanan often argued—is the most important protection we have against majorities.

Numerous other libertarian critics echo this line of criticism, accusing MacLean of being an apologist for unfettered majoritarianism. Quite obviously, this is not the point MacLean is making, and their characterization of Buchanan’s “defense of minority rights” is misleading as well. Throughout his work, Buchanan does write about minority rights, though the minority communities in question represent, not historically protected classes, but actually the proprietors of capital. Contrary to the common usage of “minority rights,” he isn’t interested in standing up for the rights of marginalized people, such as women, people of color, or LGBT communities – instead, throughout his work, he warns of unencumbered democracy’s effects on society’s elites. MacLean describes the disconnect at hand:

There seemed no way to reconcile robust individual property rights with universal voting rights. For how could the cause ever persuade a majority to agree to rules that might radically disadvantage its members in a society fast growing more unequal? Buchanan implored his readers to face facts: “how can the rich man (or the libertarian philosopher) expect the poor man to accept any new constitutional order that severely restricts the scope for fiscal transfers among groups?”

This question is intimately tied to electoral politics and the franchise, which is perhaps the most explicit demonstration of one’s political power in a democracy. Following the National Voter Registration Act (NVRA) of 1993, a piece of legislation that significantly expanded ballot access to low-income Americans. Regarding Buchanan’s reception to this legislation, MacLean writes:

[The NVRA] instructed states to facilitate participation in elections by allowing citizens to register by mail, when visiting public agencies for assistance, or when obtaining or renewing licenses at motor vehicle facilities (hence its nickname, the Motor Voter Act). By 1997, nine million net new voters had joined the electorate. To believers in voting rights, it was a huge achievement. To those who scorned the idea of a broad and inclusive electorate, it was cause for mourning. “We are increasingly enfranchising the illiterate,” grumbled Jim Buchanan, “moving rapidly toward electoral reform that will not expect voters to be able to read or follow instructions.

Fundamentally, Buchanan’s worldview couldn’t accommodate for widespread democratic participation – this is precisely the “enchainment” that MacLean diagnoses when considering his project. Buchanan appeared perturbed about the foundational premises that each citizen ought to be allotted an equal voice in governance; apparently, he paid little attention to the checks and balances embedded in our democratic structures (which may have assuaged his apprehension). Low-income citizens surely ought to have a say in government, and their participation certainly isn’t evidence of any tyranny of a majority. MacLean’s prescription isn’t to lift the checks and balances on democracy; it’s simply to have a democracy that is freed of disproportionate control by the wealthy ruling elite and special interests.

The impulse of libertarian critics to not only obfuscate Buchanan’s project, but also attack MacLean on the basis of such a weak argument, is troubling. Considering the best-case scenario, the libertarians are making their argument in good faith, and simply are, once again, demonstrating their bumbling ineptitude concerning race and (genuine) minority rights. As far as I know, Buchanan’s primary concern never appears to be historically protected classes, though this isn’t to say that Buchanan’s framework and public choice theory can’t be operationalized for such ends (there exist examples of such uses throughout public choice literature). But to exalt Buchanan as an individual who categorically stood in favor of political rights for ‘minority communities’ is clearly misguided, especially when positioned against MacLean’s arguments throughout Democracy in Chains.

To wade through the discourse of the libertarian intelligentsia is a tedious, albeit necessary endeavor; through our analysis, we’ve gotten a glimpse into how the libertarian psyche imagines white supremacy. It paints white supremacy as an interpersonal phenomenon, primarily perpetuated through intentional actions of individual actors (though remains ambiguous as to how intention is to be deciphered), oblivious to the broader systems at work. White supremacy is a fungible entity; anti-racist behaviors can ostensibly atone (or, balance) for past prejudices.

A left conception of white supremacy is still perceptive of the role assumed by interpersonal acts of bigotry, though that alone has a less significant role than the ecosystem that incubates such attitudes. A left conception is cognizant of how individuals, tacitly and actively, work to perpetuate a social, political, and economic order that maintains a status quo that subjugates certain communities and elevates others. It recognizes how ingrained these injustices are, and how American institutions, and their authorized (in)formal edicts, are rife with the legacy of white supremacy; that the genesis of the America lays on the genocide of millions of indigenous people, and that our Constitution enshrined and inaugurated the idea that non-whites were second-class citizens. Today, these legacies are more vibrant than ever: consider patterns of police killings of unarmed Black people; the racially-stratified nature of the school-to-prison pipeline; race-based voter disenfranchisement; unlawful immigrant detentions; and the racial wealth gap as some of the most overt (though, far from the only) manifestations of white supremacy. The size and depth of the ideological chasm that separates left and right conceptions of white supremacy can’t be overstated; it’s a disconnect that stretches back to the level of first principles of equality, justice, and basic history.

If one were interested in deep examinations of public choice theory or minutiae pertaining to the libertarian movement’s history, I wouldn’t necessarily recommend Democracy in Chains: there are hundreds, if not thousands, of works that primarily focus on these topics. However, if one were interested in examining a case study of, in the words of MacLean, the ways in which libertarian leaders “had no scruples about enlisting white supremacy to achieve capital supremacy,” Democracy in Chains is an invaluable resource. It brilliantly presents a case study of how the momentum of white supremacy, which was embedded into our country’s foundation, has historically been furthered along, in both subtle and systematic ways, by the libertarian right.

In fact, the libertarian movement, writ large, has been destructive to people of color (the exceptions being its recent interventions into the criminal justice sphere and the war on drugs), which MacLean elaborates throughout her masterful polemic conclusion. Some portions of this section are especially chilling, reading as if they’re taken out of a post-apocalyptic, dystopian future of America. Quoting Tyler Cowen, Buchanan’s successor at George Mason University, MacLean writes:

“While some will flourish, he says, ‘others will fall by the wayside.’ And because ‘worthy individuals’ will manage to climb their way out of poverty, ‘that will make it easier to ignore those who are left behind.’ Cowen foresees that “we will cut Medicaid for the poor.” Also, “the fiscal shortfall will come out of real wages as various cost burdens are shifted to workers” from employers and a government that does less.”

She continues:

“[The] economist prophesies lower-income parts of America ‘recreating a Mexico-like or Brazil-like environment’ complete with favelas like those in Rio de Janeiro. The ‘quality of water’ might not be what U.S. citizens are used to, but ‘partial shantytowns’ would satisfy the need for cheaper housing as ‘wage polarization’ grows and government shrinks. ‘Some version of Texas—and then some—is the future for a lot of us,’ the economist advises. ‘Get ready.’”

Make no mistake: Cowen’s forecast is the logical extension of the project that was inaugurated by the libertarian right. This cadre of libertarians comprises the nucleus of the right-wing network that has already spent billions of dollars reshaping the public discourse. The favelas and ‘partial shantytowns’ that Cowen so charmingly describes will be populated primarily by people of color, not unlike the underclass that already populates urban centers across the country, and rural areas across the Midwest and South. Those cuts to Medicaid will disproportionately affect communities of color, as will the decline in water quality, which we, of course, have already grotesquely experienced in Flint.

Giving Cowen and his peers the benefit of the doubt, I’d like to believe that this isn’t the future that libertarians desire; I doubt most libertarians individually hold animosities toward communities of color. But, analogous to Buchanan’s personal views on black schoolchildren’s education, these personal attitudes are unimportant. We must be less concerned with individual attitudes, and more concerned with the implications of particular policies given socio-historical contexts. The plain facts are that, regardless of their individual dispositions, the politics espoused by Cowen and the contemporary libertarian movement feed into the ravenous beast of white supremacy; the same case applied for Buchanan five decades ago. MacLean masterfully demonstrates the marriage between white supremacy and libertarianism, and ultimately delivers a message that bears repetition ad nauseam: libertarianism never has been, and never will be, afraid to make bedfellows with white supremacy to further its ideological ends. That alone ought to spur any individual concerned with racial justice and public welfare into action.